A tidal stream generator, often referred to as a tidal energy converter (TEC), is a machine that extracts energy from moving masses of water, in particular tides, although the term is often used in reference to machines designed to extract energy from run of river or tidal estuarine sites. Certain types of these machines function very much like underwater wind turbines, and are thus often referred to as tidal turbines. They were first conceived in the 1970s during the oil crisis.[1]

Tidal stream generators are the cheapest and the least ecologically damaging among the four main forms of tidal power generation.[2]

Similarity to wind turbines

Tidal stream generators draw energy from water currents in much the same way as wind turbines draw energy from air currents. However, the potential for power generation by an individual tidal turbine can be greater than that of similarly rated wind energy turbine. The higher density of water relative to air (water is about 800 times the density of air) means that a single generator can provide significant power at low tidal flow velocities compared with similar wind speed.[3] Given that power varies with the density of medium and the cube of velocity, water speeds of nearly one-tenth the speed of wind provide the same power for the same size of turbine system; however this limits the application in practice to places where tide speed is at least 2 knots (1 m/s) even close to neap tides. Furthermore, at higher speeds in a flow between 2 and 3 meters per second in seawater a tidal turbine can typically access four times as much energy per rotor swept area as a similarly rated power wind turbine.

Types of tidal stream generators

No standard tidal stream generator has emerged as the clear winner, among a large variety of designs. Several prototypes have shown promise with many companies making bold claims, some of which are yet to be independently verified, but they have not operated commercially for extended periods to establish performances and rates of return on investments. Some of the many companies and turbines tested are summarised in development of tidal stream generators.

The European Marine Energy Centre recognizes six principal types of tidal energy converter. They are horizontal axis turbines, vertical axis turbines, oscillating hydrofoils, venturi devices, Archimedes screws and tidal kites.[4]

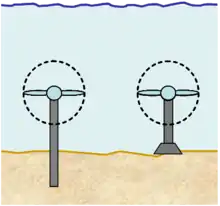

Axial turbines

These are close in concept to traditional windmills, but operate under the sea. They have most of the prototypes currently under design, development, testing or operations.

The SR2000, a prototype 2MW floating turbine developed by Orbital Marine Power in Scotland, was operated at the European Marine Energy Centre, Orkney, from 2016. It produced 3,200 MWhs of electricity in 12 months of continuous testing. It was removed in September 2018 to make way for the Orbital O2, the production model, completed in 2021.[5][6]

Tocardo,[7] a Dutch-based company, has been running tidal turbines since 2008 on the Afsluitdijk, near Den Oever.[8] Typical production data of tidal generator shown of the T100 model as applied in Den Oever.[8] Currently 1 River model (R1) and 2 tidal models (T) are in production with a 3rd T3 coming soon. Power production for the T1 is around 100 kW and around 200 kW for the T2. These are suitable for tidal currents as low 0.4 m/s.[9] Tocardo were declared bankrupt in 2019.[10] QED Naval and HydroWing have joined forces to buy tidal turbine business Tocardo in 2020.[11]

The AR-1000, a 1MW turbine developed by Atlantis Resources Corporation that was successfully deployed at the EMEC facility during the summer of 2011. The AR series are commercial scale, horizontal axis turbines designed for open ocean deployment. AR turbines feature a single rotor set with fixed pitch blades. The AR turbine is rotated as required with each tidal exchange. This is done in the slack period between tides and held in place for the optimal heading for the next tide. AR turbines are rated at 1MW @ 2.65 m/s of water flow velocity.[12]

The Kvalsund installation is south of Hammerfest, Norway at 50m depth of sea. Although still a prototype, the HS300 turbine with a reported capacity of 300 kW was connected to the grid on 13 November 2003. This made it the world's first tidal turbine delivering to the grid. The submerged structure weighed 120 tonnes and had gravity footings of 200 tonnes. Its three-blades were made in glass fibre-reinforced plastic and measured 10 metres from hub to tip. The device rotated at 7 rpm with an installed capacity of 0.3 MW.[13]

Seaflow, a 300 kW Periodflow marine current propeller type turbine was installed by Marine Current Turbines off the coast of Lynmouth, Devon, England, in 2003.[14] The 11m diameter turbine generator was fitted to a steel pile which was driven into the seabed. As a prototype, it was connected to a dump load, not to the grid.

In April 2007 Verdant Power[15] began running a prototype project in the East River between Queens and Roosevelt Island in New York City; it was the first major tidal-power project in the United States.[16] The strong currents pose challenges to the design: the blades of the 2006 and 2007 prototypes broke and new reinforced turbines were installed in September 2008.[17][18]

Following the Seaflow trial, a full-size prototype called SeaGen, was installed by Marine Current Turbines in Strangford Lough in Northern Ireland in April 2008. The turbine began to generate at full power of just over 1.2 MW in December 2008[19] and is reported to have fed 150 kW into the grid for the first time on 17 July 2008, and has now contributed more than a gigawatt hour to consumers in Northern Ireland.[20] It is currently the only commercial scale device to have been installed anywhere in the world.[21] SeaGen is made up of two axial flow rotors, each of which drive a generator. The turbines are capable of generating electricity on both the ebb and flood tides because the rotor blades can pitch through 180˚.[22]

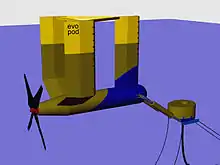

A prototype semi-submerged floating tethered tidal turbine called Evopod has been tested since June 2008[23] in Strangford Lough, Northern Ireland at 1/10 scale. The UK company developing it is called Ocean Flow Energy Ltd.[24] The advanced hull form maintains optimum heading into the tidal stream and is designed to operate in the peak flow of the water column.

In 2010, Tenax Energy of Australia proposed to put 450 turbines off the coast of Darwin, Australia, in the Clarence Strait. The turbines would feature a rotor section approximately 15 metres in diameter with a slightly larger gravity base. The turbines would operate in deep water well below shipping channels. Each turbine is forecast to produce energy for between 300 and 400 homes.[25]

Tidalstream, a UK-based company, commissioned a scaled-down Triton 3 turbine in the Thames in 2003.[26] It can be floated to its site, installed without cranes, jack-ups or divers and then ballasted into operating position. At full scale the Triton 3 in 30-50m deep water has a 3MW capacity, and the Triton 6 in 60-80m water has a capacity of up to 10MW, depending on the flow. Both platforms have man-access capability both in the operating position and in the float-out maintenance position.

European technology and innovation platform for ocean energy (ETIP OCEAN) Powering homes today, Powering nations tomorrow report 2019 makes note of record volumes being supplied through tidal stream technology.[27]

Crossflow turbines

Invented by Georges Darreius in 1923 and patented in 1929, these turbines can be deployed either vertically or horizontally.

The Gorlov turbine[28] is a variant of the Darrieus design featuring a helical design that is in a large scale, commercial pilot in South Korea,[29] starting with a 1MW plant that opened in May 2009[30] and expanding to 90MW by 2013. Neptune Renewable Energy's Proteus project[31] employs a shrouded vertical axis turbine that can be used to form an array in mainly estuarine conditions.

In April 2008, the Ocean Renewable Power Company, LLC (ORPC) successfully completed testing its proprietary turbine-generator unit (TGU) prototype at ORPC's Cobscook Bay and Western Passage tidal sites near Eastport, Maine.[32] The TGU is the core of the OCGen technology and uses advanced design cross-flow (ADCF) turbines to drive a permanent magnet generator located between the turbines and mounted on the same shaft. ORPC has developed TGU designs that can be used for generating power from river, tidal and deep water ocean currents.

Trials in the Strait of Messina, Italy, started in 2001 of the Kobold turbine concept.[33]

Flow augmented turbines

Using flow augmentation measures, for example a duct or shroud, the incident power available to a turbine can be increased. The most common example uses a shroud to increase the flow rate through the turbine, which can be either axial or crossflow.

The Australian company Tidal Energy Pty Ltd undertook successful commercial trials of efficient shrouded tidal turbines on the Gold Coast, Queensland in 2002. Tidal Energy delivered their shrouded turbine in northern Australia where some of the fastest recorded flows (11 m/s, 21 knots) are found. Two small turbines will provide 3.5 MW. Another larger 5 meter diameter turbine, capable of 800 kW in 4 m/s of flow, was planned as a tidal powered desalination showcase near Brisbane Australia.[34]

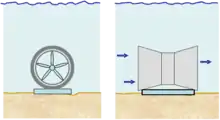

Oscillating devices

Oscillating devices do not have a rotating component, instead making use of aerofoil sections which are pushed sideways by the flow. Oscillating stream power extraction was proven with the omni- or bi-directional Wing'd Pump windmill.[35] During 2003 a 150 kW oscillating hydroplane device, the Stingray tidal stream generator, was tested off the Scottish coast.[36][37] The Stingray uses hydrofoils to create oscillation, which allows it to create hydraulic power. This hydraulic power is then used to power a hydraulic motor, which then turns a generator.[1]

Pulse Tidal operate an oscillating hydrofoil device called Pulse generator in the Humber Estuary.[38][39] Having secured funding from the EU, they are developing a commercial scale device to be commissioned 2012.[40]

The bioSTREAM tidal power conversion system, uses the biomimicry of swimming species, such as shark, tuna, and mackerel using their highly efficient Thunniform mode propulsion. It is produced by Australian company BioPower Systems.[41]

A 2 kW prototype relying on the use of two oscillating hydrofoils in a tandem configuration called oscillating wing tidal turbine has been developed at Laval University and tested successfully near Quebec City, Canada, in 2009. A hydrodynamic efficiency of 40% has been achieved during the field tests.[42][43]

Venturi effect

Venturi effect devices use a shroud or duct in order to generate a pressure differential which is used to run a secondary hydraulic circuit which is used to generate power. A device, the Hydro Venturi, is to be tested in San Francisco Bay.[44][45]

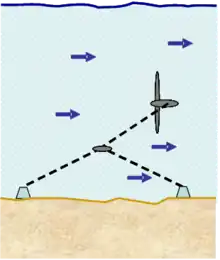

Tidal kite turbines

A tidal kite turbine is an underwater kite system or paravane that converts tidal energy into electricity by moving through the tidal stream. An estimated 1% of 2011's global energy requirements could be provided by such devices at scale.[46]

- History

Ernst Souczek of Vienna, Austria, on August 6, 1947, filed for a patent US2501696; assignor of one-half to Wolfgang Kmentt, also of Vienna. Their water kite turbine disclosure demonstrated a rich art in water-kite turbines. In similar technology, many others prior to 2006 advanced water-kite and paravane electric generating systems. In 2006, a tidal kite turbine called the Deep Green Kite was developed by Swedish company Minesto.[47] They conducted its first sea trial in Strangford Lough in Northern Ireland in the summer of 2011. The test used kites with wingspan of 1.4m.[46] In 2013 the Deep Green pilot plant began operation off Northern Ireland. The plant uses carbon fiber kites with a wingspan of 8m (or 12m[48]). Each kite has a rated power of 120 kilowatts at a tidal flow of 1.3 meters per second.[49]

- Design

Minesto's kite has a wingspan of 8–14 metres (26–46 ft). The kite has neutral buoyancy, so doesn't sink as the tide turns from ebb to flow. Each kite is equipped with a gearless turbine to generate which is transmitted by the attachment cable to a transformer and then to the electricity grid. The turbine mouth is protected to protect marine life.[46] The 14-meter version has a rated power of 850 kilowatts at 1.7 meters per second.[49]

- Operation

The kite is tethered by a cable to a fixed point. It "flies" through the current carrying a turbine. It moves in a figure-eight loop to increase the speed of the water flowing through the turbine tenfold. Force increases with the cube of velocity, offering the potential to generate 1,000-fold more energy than a stationary generator.[46] That maneuver means the kite can operate in tidal streams that move too slowly to drive earlier tidal devices, such as the SeaGen turbine.[46] The kite was expected to work in flows as low 1–2.5 metres (3 ft 3 in – 8 ft 2 in) per second, while first-generation devices need over 2.5s. Each kite will have a capacity to generate between 150 and 800 kW. They can be deployed in waters 50–300 metres (160–980 ft) deep.[46]

Tidal stream developers

There are a number of individuals and companies developing tidal energy converters across the world. A database of tidal energy developers is kept up-to-date here: Tidal energy developers[50]

Tidal stream testing

The world's first marine energy test facility was established in 2003 to kick start the development of the wave and tidal energy industry in the UK. Based in Orkney, Scotland, the European Marine Energy Centre (EMEC) has supported the deployment of more wave and tidal energy devices than at any other single site in the world. EMEC provides a variety of test sites in real sea conditions. Its grid connected tidal test site is located at the Fall of Warness, off the island of Eday, in a narrow channel which concentrates the tide as it flows between the Atlantic Ocean and North Sea. This area has a very strong tidal current, which can travel up to 4 m/s (8 knots) in spring tides. Tidal energy developers currently testing at the site include Alstom (formerly Tidal Generation Ltd), ANDRITZ HYDRO Hammerfest, OpenHydro, Scotrenewables Tidal Power, and Voith.[27]

Commercial plans

In 2010, The Crown Estate awarded an agreement for lease to MeyGen Limited, granting the option to develop a tidal stream project of up to 398MW at an offshore site between Scotland's northernmost coast and the island of Stroma. This is the largest planned tidal farm project worldwide right now, and is also the unique commercial, multi-turbine array to have commenced construction. The first phase of the MeyGen project (Phase 1A) is operational and the subsequent phases are under way.[51][12]

In 2010, RWE's npower announced that it is in partnership with Marine Current Turbines to build a tidal farm of SeaGen turbines off the coast of Anglesey in Wales,[52] near the Skerries, with planning permission given in 2013.[53] "The Skerries project located in Anglesey, Wales, will be one of the first arrays deployed using the Siemens owned Marine Current Turbines SeaGen S tidal turbines. The marine consent for the project was recently awarded, the first tidal array to be consented in Wales. The 10MW array will be fully operational in 2015." - CEO of Siemens Energy Hydro & Ocean Unit Achim Wörner. The project was shelved in 2016 after Marine Current Turbines was acquired by SIMEC Atlantis Energy.[54]

In November 2007, British company Lunar Energy announced that, in conjunction with E.ON, they would be building the world's first deep-sea tidal energy farm off the coast of Pembrokeshire in Wales. It will provide electricity for 5,000 homes. Eight underwater turbines, each 25 metres long and 15 metres high, are to be installed on the sea bottom off St David's peninsula. Construction is due to start in the summer of 2008 and the proposed tidal energy turbines, described as "a wind farm under the sea", should be operational by 2010. However, it has gone into administration less than a year after developing and testing a 400KW turbine known as DeltaStream in 2015.[55] Lunar Energy dissolved in 2019.[56]

Alderney Renewable Energy Ltd was granted a licence in 2008 and is planning to use tidal turbines to extract power from the notoriously strong tidal races around Alderney in the Channel Islands. It is estimated that up to 3 GW could be extracted. This would not only supply the island's needs but also leave a considerable surplus for export,[57] using a France-Alderney-Britain cable (FAB Link) which is expected to go online by 2020. This agreement was terminated in 2017.[58]

Nova Scotia Power has selected OpenHydro's turbine for a tidal energy demonstration project in the Bay of Fundy, Nova Scotia, Canada and Alderney Renewable Energy Ltd for the supply of tidal turbines in the Channel Islands.[59] OpenHydro was liquidated in 2018.[60]

Pulse Tidal are designing a commercial device in 2007–2009 with seven other companies who are expert in their fields.[61] The consortium was awarded an €8 million EU grant to develop the first device, which will be deployed in 2012 at the Humber estuary and generates enough power for 1,000 homes. Pulse Tidal was liquidated in 2014.[62]

ScottishPower Renewables are planning to deploy ten 1MW HS1000 devices designed by Hammerfest Strom in the Sound of Islay in 2013.[63][52]

In March 2014, the Federal Energy Regulatory Committee (FERC) approved a pilot license for Snohomish County PUD to install two OpenHydro tidal turbines in Admiralty Inlet, WA. This project is the first grid-connected two-turbine project in the US; installation is planned for the summer of 2015. The tidal turbines will use are designed to be placed directly into the seafloor at a depth of roughly 200 feet, so that there will be no effect on commercial navigation overhead. The license granted by the FERC also includes plans to protect fish, wildlife, as well as cultural and aesthetic resources, in addition to navigation. Each turbine measures 6 meters in diameter, and will generate up to 300 kW of electricity.[64] In September 2014, the project was canceled due to cost concerns.[65]

Energy calculations

Turbine power

Tidal energy converters can have varying modes of operating and therefore varying power output. If the power coefficient of the device "" is known, the equation below can be used to determine the power output of the hydrodynamic subsystem of the machine. This available power cannot exceed that imposed by the Betz limit on the power coefficient, although this can be circumvented to some degree by placing a turbine in a shroud or duct. This works, in essence, by forcing water which would not have flowed through the turbine through the rotor disk. In these situations it is the frontal area of the duct, rather than the turbine, which is used in calculating the power coefficient and therefore the Betz limit still applies to the device as a whole.

The energy available from these kinetic systems can be expressed as:

where:

- = the turbine power coefficient

- P = the power generated (in watts)

- = the density of the water (seawater is 1027 kg/m3)

- A = the sweep area of the turbine (in m2)

- V = the velocity of the flow

Relative to an open turbine in free stream, ducted turbines are capable of as much as 3 to 4 times the power of the same turbine rotor in open flow.[66]

Resource assessment

While initial assessments of the available energy in a channel have focus on calculations using the kinetic energy flux model, the limitations of tidal power generation are significantly more complicated. For example, the maximum physical possible energy extraction from a strait connecting two large basins is given to within 10% by:[67][68]

where

- = the density of the water (seawater is 1027 kg/m3)

- g = gravitational acceleration (9.80665 m/s2)

- = maximum differential water surface elevation across the channel

- = maximum volumetric flow rate though the channel.

Potential sites

As with wind power, selection of location is critical for the tidal turbine. Tidal stream systems need to be located in areas with fast currents where natural flows are concentrated between obstructions, for example at the entrances to bays and rivers, around rocky points, headlands, or between islands or other land masses. The following potential sites are under serious consideration:

- Pembrokeshire in Wales[69]

- River Severn between Wales and England[70]

- Cook Strait in New Zealand[71]

- Kaipara Harbour in New Zealand[72]

- Bay of Fundy[73] in Canada.

- East River[74][75] in the United States

- Golden Gate in the San Francisco Bay[76]

- Piscataqua River in New Hampshire[77]

- The Race of Alderney and The Swinge in the Channel Islands[57]

- The Sound of Islay, between Islay and Jura in Scotland[63]

- Pentland Firth between Caithness and the Orkney Islands, Scotland

- Humboldt County, California in the United States

- Columbia River, Oregon in the United States

- Plaquemines Parish, Louisiana in the Southern United States [78]

- Isle of Wight, England [79]

- Teddington and Ham Hydro at Teddington on the River Thames in the London suburbs, England

Modern advances in turbine technology may eventually see large amounts of power generated from the ocean, especially tidal currents using the tidal stream designs but also from the major thermal current systems such as the Gulf Stream, which is covered by the more general term marine current power. Tidal stream turbines may be arrayed in high-velocity areas where natural tidal current flows are concentrated such as the west and east coasts of Canada, the Strait of Gibraltar, the Bosporus, and numerous sites in Southeast Asia and Australia. Such flows occur almost anywhere where there are entrances to bays and rivers, or between land masses where water currents are concentrated.

Environmental impacts

The main environmental concern with tidal energy is associated with blade strike and entanglement of marine organisms as high speed water increases the risk of organisms being pushed near or through these devices. As with all offshore renewable energies, there is also a concern about how the creation of EMF and acoustic outputs may affect marine organisms. Because these devices are in the water, the acoustic output can be greater than those created with offshore wind energy. Depending on the frequency and amplitude of sound generated by the tidal energy devices, this acoustic output can have varying effects on marine mammals (particularly those who echolocate to communicate and navigate in the marine environment such as dolphins and whales). Tidal energy removal can also cause environmental concerns such as degrading farfield water quality and disrupting sediment processes. Depending on the size of the project, these effects can range from small traces of sediment build up near the tidal device to severely affecting nearshore ecosystems and processes.[80]

One study of the Roosevelt Island Tidal Energy (RITE, Verdant Power) project in the East River (New York City), used 24 split beam hydroacoustic sensors (scientific echosounder) to detect and track the movement of fish both upstream and downstream of each of six turbines. The results suggested (1) very few fish using this portion of the river, (2) those fish which did use this area were not using the portion of the river which would subject them to blade strikes, and (3) no evidence of fish traveling through blade areas.[81]

Work is currently being conducted by the Northwest National Marine Renewable Energy Center (NNMREC[82]) to explore and establish tools and protocols for assessment of physical and biological conditions and monitor environmental changes associated with tidal energy development.

See also

References

- 1 2 Jones, Anthony T., and Adam Westwood. "Power from the oceans: wind energy industries are growing, and as we look for alternative power sources, the growth potential is through the roof. Two industry watchers take a look at generating energy from wind and wave action and the potential to alter." The Futurist 39.1 (2005): 37(5). GALE Expanded Academic ASAP. Web. 8 October 2009.

- ↑ "Tidal power". Archived from the original on 23 September 2010. Retrieved 1 November 2010.

- ↑ "Has Welsh Firm Caught The Tide? - TIME". January 20, 2011. Archived from the original on 2011-01-20.

- ↑ "Tidal devices : EMEC: European Marine Energy Centre".

- ↑ "ScotRenewables SR2000 at EMEC". Tethys. Retrieved 26 November 2020.

- ↑ "Orbital Marine Power Launches O2: World's Most Powerful Tidal Turbine" (Press release). Edinburgh: Orbital Marine Power. Retrieved 2021-04-29.

- ↑ "Tocardo home". Retrieved 2015-04-17.

- 1 2 "Projects". 23 October 2023.

- ↑ "Tocardo T-1".

- ↑ "Tocardo Declares Bankruptcy". 11 October 2019.

- ↑ "New EU tidal joint venture formed with Dutch acquisition". 8 January 2020.

- 1 2 Chen, Hao; Tang, Tianhao; Ait-Ahmed, Nadia; Benbouzid, Mohamed El Hachemi; Machmoum, Mohamed; Zaim, Mohamed El-Hadi (2018). "Attraction, Challenge and Current Status of Marine Current Energy". IEEE Access. 6: 12665–12685. Bibcode:2018IEEEA...612665C. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2018.2795708. S2CID 4110420.

- ↑ "Kvalsund Tidal Turbine Prototype | Tethys".

- ↑ "Read about the first open-sea tidal turbine generator off Lynmouth, Devon". REUK. Retrieved 2013-04-28.

- ↑ "Verdant Power". Verdant Power. 2012-01-23. Archived from the original on 2013-04-20. Retrieved 2013-04-28.

- ↑ MIT Technology Review, April 2007 Archived 2010-11-12 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved August 24, 2008.

- ↑ Robin Shulman (September 20, 2008). "N.Y. Tests Turbines to Produce Power. City Taps Current Of the East River". Washington Post. Retrieved 2008-10-09.

- ↑ Kate Galbraith (September 22, 2008). "Power From the Restless Sea Stirs the Imagination". New York Times. Retrieved 2008-10-09.

- ↑ "SIMEC Atlantis Energy | Turbines and Engineering Services". Archived from the original on September 25, 2010. Retrieved November 8, 2010.

- ↑ First connection to the grid Archived September 25, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "· Sea Generation Tidal Turbine". Marineturbines.com. Retrieved 2013-04-28.

- ↑ Marine Current Turbines. "Technology." Marine Current Turbines. Marine Current Turbines, n.d. Web. 5 October 2009. <http://www.marineturbines.com/21/ technology/>.

- ↑ http://www.oceanflowenergy.com/news-details.aspx?id=6 Archived 2009-05-11 at the Wayback Machine Ocean Flow Energy Ltd announce the start of their testing in Strangford Lough

- ↑ "Ocean Flow Energy company website". Oceanflowenergy.com. Retrieved 2013-04-28.

- ↑ Nigel Adlam (2010-01-29). "Tidal power project could run all homes". Northern Territory News. Archived from the original on 2011-12-24. Retrieved 2010-06-06.

- ↑ "Triton Home". Tidalstream.co.uk. Retrieved 2013-04-28.

- 1 2 "Home". emec.org.uk.

- ↑ Gorlov Turbine Archived February 5, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Gorlov Turbines in Koreas". Worldchanging.com. 1999-02-22. Archived from the original on 2013-05-11. Retrieved 2013-04-28.

- ↑ "South Korea starts up, to expand 1-MW Jindo Uldolmok tidal project". Hydro World. 2009. Archived from the original on 2010-09-01. Retrieved 2010-11-08.

- ↑ "Proteus". Neptunerenewableenergy.com. 2013-02-07. Retrieved 2013-04-28.

- ↑ "Tide is slowly rising in interest in ocean power". Mass High Tech: The Journal of New England Technology. August 1, 2008. Archived from the original on December 26, 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-11.

- ↑ "A.D.A.Group". Archived from the original on March 25, 2009.

- ↑ "Tidal Energy - the Tidal Energy Advantage".

- ↑ "Wing'd Pump Windmill". Econologica.org. Retrieved 2013-04-28.

- ↑ "Stingray". Engb.com. Retrieved 2013-04-28.

- ↑ https://tethys.pnnl.gov/sites/default/files/publications/Stingray_Tidal_Stream_Energy_Device.pdf

- ↑ "BBC Look North "A tidal power project in the Humber has generated its first batch of electricity"". Youtube.com. 2009-08-06. Archived from the original on 2021-12-21. Retrieved 2013-04-28.

- ↑ "Full scale demonstration prototype tidal stream generator". Community Research and Development Information Service (CORDIS).

- ↑ Don Pratt (3 December 2009). "EU Grant reported by The Engineer". Theengineer.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2012-03-14. Retrieved 2013-04-28.

- ↑ "Shark biomimicry produces renewable energy system". Mongabay Environmental News. November 2006.

- ↑ "HAO turbine". Hydrolienne.fsg.ulaval.ca. Archived from the original on 2012-03-14. Retrieved 2013-04-28.

- ↑ https://www.lmfn.ulaval.ca/fileadmin/lmfn/documents/poster_pdf/TKinsey_INORE_SYMPOSIUM_HAO_2010.pdf

- ↑ Seth Wolf (2004-07-27). "San Francisco Bay Guardian News". Sfbg.com. Archived from the original on 2010-11-02. Retrieved 2013-04-28.

- ↑ "Hydro | VerdErg Renewable Energy".

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Carrington, Damian (2011-03-02). "Underwater kite-turbine may turn tides into green electricity | Damian Carrington | Environment". theguardian.com. Retrieved 2013-12-03.

- ↑ "The future of renewable energy | Minesto".

- ↑ "Deep Green underwater kite to generate electricity (w/ Video)". Phys.org. Retrieved 2013-12-03.

- 1 2 Tweed, Katherine (2013-11-14). "Underwater Kite Harvests Energy From Slow Currents - IEEE Spectrum". Spectrum.ieee.org. Retrieved 2013-12-03.

- ↑ "Tidal developers : EMEC: European Marine Energy Centre".

- ↑ "MeyGen - Tidal Projects". Archived from the original on 2020-12-27. Retrieved 2020-10-07.

- 1 2 "Renewable Energy Focus - Journal - Elsevier".

- ↑ RWE npower renewables Sites > Projects in Development > Marine > Skerries > The Proposal : Anglesey Skerries Tidal Stream Array. Retrieved February 26, 2010.

- ↑ "£70m Anglesey tidal project is shelved - again". 22 March 2016.

- ↑ "Administrators seek buyer for Tidal Energy Ltd". BBC News. 24 October 2016.

- ↑ "LUNAR ENERGY POWER LIMITED overview - Find and update company information - GOV.UK". find-and-update.company-information.service.gov.uk.

- 1 2 "Alderney Renewable Energy Ltd". Are.gb.com. Archived from the original on 2012-04-23. Retrieved 2013-04-28.

- ↑ "Turbulent tides hit Alderney". 25 May 2017.

- ↑ "Open Hydro". Archived from the original on 2010-10-23. Retrieved 2010-11-08.

- ↑ "Tides wash away OpenHydro". 26 July 2018.

- ↑ "Ways to Save Energy - How to save energy and the best ways to save energy in the home". www.savingenergyathome.co.uk.

- ↑ "Sad news for Pulse Tidal". Analysis.newenergyupdate.com. Reuters. 22 April 2014. Retrieved 2022-09-12.

- 1 2 "Islay Energy Trust Home". www.islayenergytrust.org.uk.

- ↑ "Admiralty Inlet Pilot Tidal Project | Tethys". Archived from the original on 2014-05-26. Retrieved 2014-05-07.

- ↑ "Snohomish County PUD drops tidal-energy project". 30 September 2014.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-09-13. Retrieved 2013-04-28.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) tidal paper on cyberiad.net - ↑ Atwater, J.F., Lawrence, G.A. (2008) Limitations on Tidal Power Generation in a Channel, Proceedings of the 10th World Renewable Energy Congress. (pp 947–952)

- ↑ Garrett, C. and Cummins, P. (2005). "The power potential of tidal currents in channels." Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, Vol. 461, London. The Royal Society, 2563–2572

- ↑ Builder & Engineer - Pembrokeshire tidal barrage moves forward Archived 2011-09-11 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "News: The latest news, sport, weather and events from WalesOnline". Wales Online.

- ↑ "EnergyBulletin.net | NZ: Chance to turn the tide of power supply | Energy and Peak Oil News". May 22, 2005. Archived from the original on 2005-05-22.

- ↑ "Harnessing the power of the sea". Energy NZ, Vol 1, No 1. Winter 2007. Archived from the original on 2011-07-24.

- ↑ Bay of Fundy to get three test turbines | Cleantech.com Archived 2008-07-04 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Shulman, Robin (September 20, 2008). "N.Y. Tests Turbines to Produce Power". The Washington Post. ISSN 0740-5421. Retrieved 2008-09-20.

- ↑ "Verdant Power". Archived from the original on December 6, 2010.

- ↑ "Google Sites: Sign-in" (PDF). accounts.google.com. Archived from the original on March 18, 2009.

- ↑ "Tidal power from Piscataqua River?". Archived from the original on 2012-09-27. Retrieved 2010-11-08.

- ↑ "Funding, paperwork slow ambitious plans to produce power using underwater turbines in Mississippi River | Business News | nola.com". 24 April 2011.

- ↑ "Isle of Wight tidal energy demonstration site plans unveiled". BBC News. 2014-03-20.

- ↑ "Tethys | Environmental Effects of Wind and Marine Renewable Energy". tethys.pnnl.gov.

- ↑ "Roosevelt Island Tidal Energy (RITE) Environmental Assessment Project | Tethys". tethys.pnnl.gov.

- ↑ "PMEC". 22 August 2022.