| Stourbridge Town Hall | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Stourbridge Town Hall | |

| Location | Market Street, Stourbridge |

| Coordinates | 52°27′26″N 2°08′51″W / 52.4571°N 2.1476°W |

| Built | 1887 |

| Architect | Thomas Robinson |

| Architectural style(s) | Renaissance style |

Listed Building – Grade II | |

| Official name | The Town Hall |

| Designated | 25 April 1978 |

| Reference no. | 1251260 |

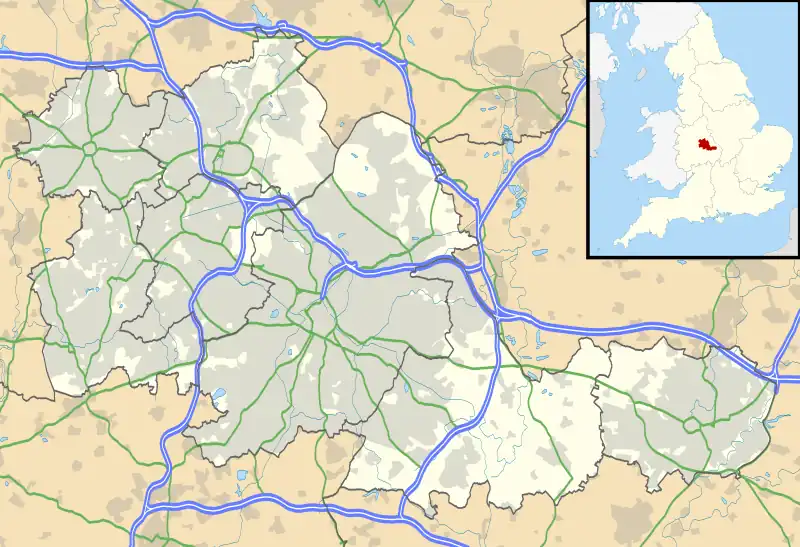

Shown in the West Midlands | |

Stourbridge Town Hall is a municipal building in Market Street, Stourbridge, West Midlands, England. The town hall, which was the headquarters of Stourbridge Borough Council, is a Grade II listed building.[1]

History

.jpg.webp)

The first town hall in Stourbridge was located in the High Street and was completed in the late 15th century.[2] It was designed with arcading on the ground floor to allow markets to be held; six pillars supported an assembly room which was established on the first floor: it was demolished as part of a road-widening scheme in 1773.[2] A new market hall was designed by John White in the neoclassical style, built slightly to the south west of the original structure and was opened on 27 October 1827.[2][lower-alpha 1] The market hall was supplemented by a corn exchange which was built on Market Street, behind White's building, in 1850.[2] Civic meetings were typically held in the corn exchange at that time.[2]

In the 1880s civic leaders decided to demolish the old corn exchange and to procure a new town hall, financed by public subscription, to commemorate the Golden Jubilee of Queen Victoria.[3] The new building was designed by Thomas Robinson in the Renaissance style, built in red brick with terracotta dressings at a cost of £5,000 and was officially opened by the Lord Lieutenant of Worcestershire, Lord Beauchamp, on 14 November 1887.[4] The complex was supplemented by a new corn exchange and a new fire station which opened the following year.[3] The design involved a main hall which was just five bays wide and set back from the Market Street frontage with a cupola above. In front of the main hall was a seven-bay screen which formed the central section of a larger frontage which was seventeen bays wide. The middle bay of the central section contained an arched doorway with an iron gate flanked by paired pilasters supporting an entablature with a date stone and a segmental gable which contained a carved tympanum. To the left of the central section was a two-bay section which featured a tall tower with a pyramid-shaped roof, a belfry and a weather vane. At each end there were four-bay pavilions, each of which also featured a central gable which contained a carved tympanum.[1]

On 29 January 1894, the statesman, Joseph Chamberlain, made an important speech at the town hall in which he was highly critical of the government of William Gladstone:[5] Gladstone was compelled to resign in March 1894.[6] After significant population growth, largely associated with the glass making industry, the town became an urban district in late 1894.[7] One of the founders of the Labour Party, Keir Hardie, made a speech at the town hall on 1 November 1913 during which he referred to the importance of women's suffrage.[8] The town went on to become a municipal borough with the town hall as its headquarters in 1914.[7]

The town hall became a popular music venue in the 1960s[9] hosting performers including rock bands such as The Hollies in July 1965,[10] The Who in May 1966[11] and The Yardbirds in July 1966.[10] It continued to serve as the headquarters of the local municipal borough council for much of the 20th century but ceased to be the local seat of government when the enlarged Dudley Metropolitan Borough Council was formed in 1974.[12] The locally-born singer, Lyndsie Holland, was a regular performer in Gilbert and Sullivan operettas in the building in the 1980s.[13] In November 2019, Dudley Council invited proposals from local community groups who were interested in taking over the management of the town hall.[14]

Notes

References

- 1 2 Historic England. "The Town Hall (1251260)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 20 February 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Smith, Edgar. "Six Market Sites: Stourbridge" (PDF). Hagley Historical and Field Society. p. 14. Retrieved 20 February 2021.

- 1 2 Perry, Nigel (2019). A History of Stourbridge. The History Press. ISBN 978-0750993135.

- ↑ "Stourbridge Town Hall". Welcome to Stourbridge. Retrieved 20 February 2021.

- ↑ Burke, Edmund (1895). Annual Register. Longmans, Green & Co. p. 17.

- ↑ Matthew, H. C. G. (1997). Gladstone: 1875–1898. Clarendon Press. p. 355. ISBN 978-0198204053.

- 1 2 "Stourbridge UD/MB". Vision of Britain. Retrieved 20 February 2021.

- ↑ Barnsby, George J. (1994). Votes for Women: The Struggle for the Vote in the Black Country 1900-1918. Socialist History Society. ISBN 978-0905679099.

- ↑ "Stourbridge Town Hall". BBC. Retrieved 20 February 2021.

- 1 2 "Stourbridge Town Hall". Setlist. Retrieved 20 February 2021.

- ↑ Neill, Andrew; Kent, Matthew (2009). Anyway, Anyhow, Anywhere: The Complete Chronicle of the WHO 1958–1978. Sterling Publishing Company. p. 305. ISBN 978-1402766916.

- ↑ Local Government Act 1972. 1972 c.70. The Stationery Office Ltd. 1997. ISBN 0-10-547072-4.

- ↑ "Sadness at acclaimed Stourbridge-born singer's death". Stourbridge News. 16 April 2014. Retrieved 20 February 2021.

- ↑ "Volunteers needed to take on Stourbridge Town Hall". Express and Star. 2 November 2019. Retrieved 20 February 2021.