| Stranger on the Third Floor | |

|---|---|

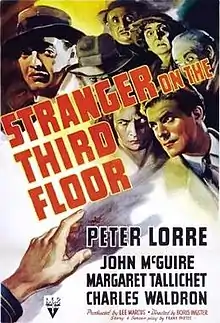

theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Boris Ingster |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Story by | Frank Partos |

| Produced by | Lee S. Marcus |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Nicholas Musuraca |

| Edited by | Harry Marker |

| Music by | Roy Webb |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | RKO Radio Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 62 or 66-67 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $171,200 (estimated) |

Stranger on the Third Floor is a 1940 American film noir directed by Boris Ingster and starring Peter Lorre, John McGuire, Margaret Tallichet, and Charles Waldron, and featuring Elisha Cook Jr. It was written by Frank Partos. Modern research has shown that Nathanael West wrote the final version of the screenplay, but was uncredited.[2][1]

Stranger on the Third Floor is often cited as the first "true" film noir of the classic period (1940–1959),[3][4][5] though other films that fit the genre such as Rebecca and They Drive by Night were released earlier. Nonetheless, it has many of the hallmarks of film noir: an urban setting, heavy shadows, diagonal lines, voice-over narration, a dream sequence, low camera angles shooting up multi-story staircases, and an innocent protagonist desperate to clear himself after being falsely accused of a crime.

Plot

Reporter Michael Ward is the key witness in a murder trial. His evidence – that he saw the accused, Joe Briggs, standing over the body of a man in a diner – is instrumental in having Briggs found guilty.

Afterwards, Ward's fiancée Jane begins worrying that Ward may not have been correct in what he saw; eventually Ward becomes haunted by this question.

One evening, outside his room in the house where he lives, Ward sees an odd-looking stranger. He chases this man down the stairs and out the front door where Ward loses track of him. Ward feels that his neighbor, a man he hates, may have been killed by the stranger. Ward has a terrifying dream in which the neighbor is indeed murdered and he comes under suspicion.

It turns out the neighbor was killed the same way as the man in the diner. Ward finds the body, notifies police and points out the similarities in the two murders. He is arrested and, in order to clear him, Jane sets out to find the strange man.

Cast

- Peter Lorre as The Stranger

- John McGuire as Mike Ward

- Margaret Tallichet as Jane

- Charles Waldron as District Attorney

- Elisha Cook Jr. as Joe Briggs

- Charles Halton as Albert Meng

- Ethel Griffies as Mrs. Kane, Michael's landlady

- Cliff Clark as Martin

- Oscar O'Shea as the Judge

- Alec Craig as Briggs' Defense Attorney

- Emory Parnell as Detective

Margaret Tallichet, who played Jane, married film director William Wyler on October 23, 1938, at the home of actor Walter Huston[6] and continued to make films, including Stranger on the Third Floor in 1940. She made two more films, then retired from acting.

Production

Stranger on the Third Floor was Boris Ingster's directorial debut.[1] Ingster, who was born in Latvia, was formerly a writer, and an associate of noted Russian director Sergei Eisenstein. Ingster would later become a television producer. He directed only three feature films in his career.[7][8]

In the introduction to Turner Classic Movies' Noir Alley presentation of the film, Eddie Muller compared the style of the film to that of German Expressionist films.[8] Jeremy Arnold writes that the film's "extraordinary look and tone are the product of stylized sets, bizarre angles and lighting, and a powerful blurring of dream and reality – qualities strongly influenced by German expressionist films of the 1920s."[7] Robert Portfino called it "a distinct break in style and substance with the preceding mystery, crime, detection and horror films of the 1930s."[7] In their book Kings of the Bs, Todd McCarthy and Charles Flynn wrote that Stranger on the Third Floor "is extremely audacious in terms of what it seeks to say about American society...The trial of the ex-con is a vicious rendering of the American legal system hard at work on an impoverished victim...[T]he sinister role of police and prosecutors in obtaining confessions and convictions [are] hallmarks of the hard-boiled literature that paralleled and predicted what we call film noir."[7]

Van Nest Polglase, who has been called "one of the most influential production designers in American cinema", was the film's art director. He had previously worked on King Kong in 1933 and The Hunchback of Notre Dame in 1939, and worked on the sets for Citizen Kane. His work on Stranger on the Third Floor "contributes mightily to the claustrophobic feel of the movie."[7] Muller calls his work on this film "spectacular".[8] In addition, the work of special effects artist Vernon L. Walker was excellent despite the constraints of a B movie budget, and the score of Roy Webb, who was RKO's house composer at the time, contributes significantly to the film's mood.[7]

Reception

Upon its release in 1940, Bosley Crowther of The New York Times called the film pretentious and derivative of French and Russian films, and wrote "John McGuire and Margaret Tallichet, as the reporter and his girl, are permitted to act half-way normal, it is true. But in every other respect, including Peter Lorre's brief role as the whack, it is utterly wild. The notion seems to have been that the way to put a psychological melodrama across is to pile on the sound effects and trick up the photography."[9]

The staff writer at Variety also believed the film was derivative, and wrote "The familiar artifice of placing the scribe in parallel plight, with the newspaperman arrested for two slayings and only clearing himself because of his sweetheart's persistent search for the real slayer, is used...Boris Ingster's direction is too studied and when original, lacks the flair to hold attention. It's a film too arty for average audiences, and too humdrum for others."[10]

Dave Kehr of the Chicago Reader wrote: "An RKO B-film from 1940, done up in high Hollywood expressionism. It's absurdly overwrought (which was often the problem with the German variety), but interesting for it. The director, Boris Ingster, is better with shadows than with actors – venetian blinds carve up the characters with more fateful force than Paul Schrader's similar gambit in American Gigolo, and there's a dream sequence that has to be seen to be disbelieved."[11]

Another film reviewer, P.S. Harrison, wrote that "at [the film's] conclusion, one feels as if one had gone through a nightmare."[7]

On Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds an approval rating of 86%, with an average rating of 6.6/10, based on seven professional reviews.[12]

References

Notes

- 1 2 3 Stranger on the Third Floor at the American Film Institute Catalog

- ↑ Biesen, Sheri Chinen (2005). Blackout: World War II and the Origins of Film Noir. JHU Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-8018-8217-3.

- ↑ See, e.g., Lyons (2000), p. 36 ("RKO is usually cited as having produced the first true film noir, Stranger on the Third Floor"); Server (1998), p. 158 ("Often credited as the 'first' film noir")

- ↑ Silver, Alain, and Elizabeth Ward, eds. Film Noir: An Encyclopedic Reference to the American Style, film noir review and analysis by Bob Porfirio, page 269, 3rd edition, 1992. Woodstock, New York: The Overlook Press. ISBN 0-87951-479-5.

- ↑ Selby, Spencer. Dark City: The Film Noir. Film listed as: "often referred to as the first true and total film noir", #398 on page 183, 1984. Jefferson, N.C. & London: McFarland Publishing. ISBN 0-89950-103-6.

- ↑ Associated Press, "Margaret Tallichet a Bride," New York Times, October 24, 1938.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Arnold, Jeremy (ndg) "Stranger on the Third Floor (1940)" TCM.com

- 1 2 3 Muller, Eddie (March 11, 2018) Intro and outro to Turner Classic Movie's presentation of Stranger on the Third Floor

- ↑ Crowther, Bosley (September 2, 1940). "Stranger on the Third Floor (1940)". The New York Times. Retrieved December 29, 2007.

- ↑ Staff (September 4, 1940). "Review: Stranger on the 3rd Floor". Variety. Vol. 139, no. 13. p. 18. Retrieved June 6, 2015 – via Internet Archive.

- ↑ Kehr, Dave. "Stranger on the Third Floor". Chicago Reader. Retrieved June 6, 2015.

- ↑ "Stranger on the Third Floor (1940)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved June 6, 2015.

Bibliography