| Streptococcus anginosus | |

|---|---|

| |

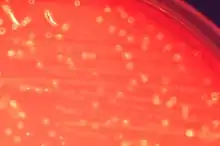

| Cultures of Streptococcus anginosus on blood agar | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Bacteria |

| Phylum: | Bacillota |

| Class: | Bacilli |

| Order: | Lactobacillales |

| Family: | Streptococcaceae |

| Genus: | Streptococcus |

| Species: | S. anginosus |

| Binomial name | |

| Streptococcus anginosus (Andrewes and Horder 1906) Smith and Sherman 1938 (Approved Lists 1980) | |

Streptococcus anginosus is a species of Streptococcus.[1] This species, Streptococcus intermedius, and Streptococcus constellatus constitute the anginosus group, which is sometimes also referred to as the milleri group after the previously assumed but later refuted idea of a single species Streptococcus milleri. Phylogenetic relatedness of S. anginosus, S. constellatus, and S. intermedius has been confirmed by rRNA sequence analysis.[2]

General characteristics

The majority of Streptococcus anginosus strains produce acetoin from glucose, ferment lactose, trehalose, salicin, and sucrose, and hydrolyze esculin and arginine. Carbon dioxide can stimulate growth or is even required for growth in certain strains. Streptococcus anginosus may be beta-hemolytic or nonhemolytic. The small colonies often give off a distinct odor of butterscotch or caramel. Among the nonhemolytic strains, certain ones produced the alpha reaction on blood agar.[3] However, of isolates examined in one study, 56% were non-hemolytic, 25% were beta-hemolytic, and only 19% were alpha-hemolytic.[4]

Infections

Streptococcus anginosus is part of the human bacteria flora, but can cause diseases including brain and liver abscesses under certain circumstances. The habitat of S. anginosus is a wide variety of sites inside the human body. Cultures have been taken from the mouth, sinuses, throat, feces, and vagina, yielding both hemolytic (mouth) and nonhemolytic (fecal and vaginal) strains. Because of the commonplace with this bacterium and the human body, there are a number of infections that are caused by S. anginosus.[3]

With S. anginosus blood stream infections (bacteremia) it has been widely reported that the source is often from an abscess. In one series of 51 cases of Strep milleri group bacteremia, 6 were associated with abscesses.[5]

Pyogenic liver abscess is associated with S. anginosus and in studies in the 1970s was reported to be the most common cause of hepatic abscess.[6] It was also reported that S. anginosus rarely causes infections in healthy individuals but instead it is usually the immunodeficient individuals who were victim to this bacterium. A case study was reported on a 40-year-old man who frequently drank alcohol and had poor oral hygiene. He was admitted to hospital with high fever and malaise. During diagnostic testing, an abscess was found on his liver, from which 550cc of hemopurulent exudate was drained. The exudate was cultured and S. anginosus was found. Disc diffusion technique revealed that bacterium was sensitive to penicillin. Patient was asymptomatic on 30th day of treatment. It was noted that the duration of symptoms is longer with liver abscesses associated with S. anginosus than with other microorganisms.[7]

Another study showed a case with a diagnosis of sympathetic empyema that was likely secondary to splenic abscess. Cultures of both sites grew Streptococcus anginosus. The empyema responded well to treatments however the splenic abscess required three weeks of drainage before the abscess resolved. Authors noted that there were no known cases of sympathetic empyema caused by Streptococcus anginosus.[8]

Treatments

There are several antimicrobial resistant strains of this bacterium. Most Streptococcus milleri strains are resistant to bacitracin and nitrofurazone, and sulfonamides are totally ineffective.[9] However, most strains studied have been shown to be susceptible to penicillin, ampicillin, erythromycin, and tetracycline.[10]

References

- ↑ Morita E, Narikiyo M, Yokoyama A, et al. (December 2005). "Predominant presence of Streptococcus anginosus in the saliva of alcoholics". Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 20 (6): 362–5. doi:10.1111/j.1399-302X.2005.00242.x. PMID 16238596.

- ↑ Jacobs, JA; Schot, CS; Schouls, LM (May 2000). "The Streptococcus anginosus species comprises five 16S rRNA ribogroups with different phenotypic characteristics and clinical relevance". International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 50 (3): 1073–9. doi:10.1099/00207713-50-3-1073. PMID 10843047.

- 1 2 Ruoff, KL (January 1988). "Streptococcus anginosus ("Streptococcus milleri"): the unrecognized pathogen". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 1 (1): 102–8. doi:10.1128/CMR.1.1.102. PMC 358032. PMID 3060239.

- ↑ Ball, Lyn C.; Parker, M. T. (14 May 2009). "The cultural and biochemical characters of Streptococcus milleri strains isolated from human sources". Journal of Hygiene. 82 (1): 63–78. doi:10.1017/S002217240002547X. PMC 2130127. PMID 762404.

- ↑ Bert, Frédéric; Lancelin, Morgane Bariou; Zechovsky, Nicole Lambert (1 August 1998). "Clinical Significance of Bacteremia Involving the "Streptococcus milleri" Group: 51 Cases and Review". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 27 (2): 385–387. doi:10.1086/514658. ISSN 1058-4838. PMID 9709892.

- ↑ Rawla, P; Vellipuram, AR; Bandaru, SS; Pradeep Raj, J (December 2017). "Colon Carcinoma Presenting as Streptococcus anginosus Bacteremia and Liver Abscess". Gastroenterology Research. 10 (6): 376–379. doi:10.14740/gr884w. PMC 5755642. PMID 29317948.

- ↑ Yilmaz, hava (1 June 2012). "Liver abscess associated with an oral flora bacterium Streptococcus anginosus". Journal of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. 2 (1): 33–35. doi:10.5799/ahinjs.02.2012.01.0039.

- ↑ Wissa, Raschke, Mathew. "Sympathetic Empyema Arising from Streptococcus anginosus Splenic Abscess." Southwest Journal of Pulmonary and Critical Care. 2012. Vol. 4, pp48-50

- ↑ Poole, P M; Wilson, G (1 August 1976). "Infection with minute-colony-forming beta-haemolytic streptococci". Journal of Clinical Pathology. 29 (8): 740–745. doi:10.1136/jcp.29.8.740. PMC 476157. PMID 956456.

- ↑ Shlaes; et al. (1981). "Infections due to Lancefield group F and related streptococci". Medicine (Baltimore). 60 (3): 197–207. doi:10.1097/00005792-198105000-00003. PMID 7231153.