Sugiyama Waichi (1614–1694) was a Japanese acupuncturist, widely regarded as the "Father of Japanese Acupuncture".

An eye-disease in infancy blinded Sugiyama from a very early age. At the age of ten he moved from Kyoto to Edo (Tokyo) to study massage and other therapeutic techniques under Ryomei Irie, one of the most famous medical practitioners of the era.[1] His apprenticeship was short; Irie quickly dismissing him as "dull". On his way back to Kyoto, Sugiyama fasted and prayed for 100 days in a Cave, where he reputedly discovered the secret of the shinkan ("insertion tube") after pricking himself on a needle wrapped in a leaf.[2][3]

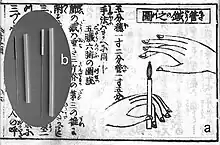

His development of the shinkan, combined with his use of extremely fine gold and silver needles, allowed for comparatively painless acupuncture, and resulted in considerable expansion of the art; for this reason he is often referred to as the "father of Japanese acupuncture". He started around forty-five schools teaching massage and acupuncture to other blind people, resulting in the prevalent association in Japan between blindness and physical therapy.[4] After Sugiyama effected a cure for a neurotic disease afflicting shōgun Tokugawa Tsunayoshi his work received official state endorsement, which greatly increased the popularity of his schools.[5][6]

Sugiyama's grave can be found in the graveyard of the Miroku-Temple in Tokyo (Sumida-ku).

Sugiyama's teachings were recorded by his disciples and printed for the first time in 1880: Ryōji no taigaishū, Senshin no yōshū, and Igaku setsuyōshū.

Much of Japanese acupuncture has been influenced by the study of the Nan Jing the Chinese Medical Classic.[7]

External links

- Ryōji no taigaishū (1880 edition, National Diet Library Tokyo)

- Senshin no yōshū (1911 edition, National Diet Library Tokyo)

- Japanese Website of the Sugiyama Society ( Sugiyamakengyō itoku kenshō-kai)

References

- ↑ Kenkichi Yamaguchi; Frederic De Garis; Atsuharu Sakai (1964). We Japanese: being descriptions of many of the customs, manners, ceremonies, festivals, arts and crafts of the Japanese, besides numerous other subjects. Fujiya Hotel. p. 255. Retrieved 11 May 2012.

- ↑ Carl Dubitsky (1 May 1997). Bodywork Shiatsu: Bringing the Art of Finger Pressure to the Massage Table. Inner Traditions * Bear & Company. pp. 4–. ISBN 978-0-89281-526-5. Retrieved 11 May 2012.

- ↑ M. Hyodo; Tsutomu Oyama (1 December 1992). The Pain Clinic IV: Proceedings of the Fourth International Symposium, Kyoto, Japan, 1990. VSP. pp. 111–. ISBN 978-90-6764-147-0. Retrieved 11 May 2012.

- ↑ Stephen Birch; Junko Ida (1 May 1998). Japanese Acupuncture: A Clinical Guide. Paradigm Publications. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-912111-42-1. Retrieved 11 May 2012.

- ↑ Dr. DoAnn T. Kaneko (2006). Shiatsu Anma Therapy. DoAnn's Short & Long Forms. HMAUCHI. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-9772128-0-4. Retrieved 11 May 2012.

- ↑ Thieme Almanac; Michael McCarthy (3 January 2007). Thieme Almanac 2007: Acupuncture and Chinese Medicine. Thieme. p. 169. ISBN 978-1-58890-425-6. Retrieved 11 May 2012.

- ↑ Baracco, Luciano (2011). National Integration and Contested Autonomy: The Caribbean Coast of Nicaragua. Algora Publishing. ISBN 978-0-87586-823-3.