| Sullivan Expedition | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of American Revolutionary War | |||||||

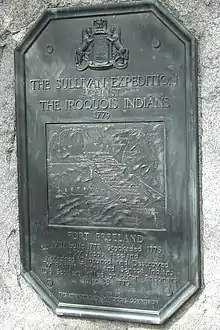

Commemorative plaque of the Sullivan Expedition in Lodi, New York | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Iroquois Confederacy |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Sayenqueraghta Cornplanter Joseph Brant Little Beard John Butler |

John Sullivan James Clinton Edward Hand Enoch Poor William Maxwell Daniel Brodhead | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

1,000 Iroquois 200–250 Butler's Rangers) | 4,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Unknown | 33 killed, 41 wounded[1] | ||||||

|

Total Iroquois casualties: 5,000 refugees, 4,500 deaths from starvation, exposure, disease, and violence (per Koehler)[2] | |||||||

The 1779 Sullivan Expedition (also known as the Sullivan-Clinton Expedition, the Sullivan Campaign, and the Sullivan-Clinton Genocide[2]) was a United States military campaign during the American Revolutionary War, lasting from June to October 1779, against the four British allied nations of the Iroquois (also known as the Haudenosaunee). The campaign was ordered by George Washington in response to the 1778 Iroquois and British attacks on Wyoming, German Flatts, and Cherry Valley, to earn bounties on scalps offered by the King that year.[3] The campaign had the aim of "taking the war home to the enemy to break their morale".[1] The Continental Army carried out a scorched-earth campaign in the territory of the Iroquois Confederacy (also known as the Longhouse Confederacy) in what is now western and central New York.

The expedition was largely successful, with more than 40 Iroquois villages razed and their crops and food stores destroyed. The campaign drove 5,000 Iroquois to Fort Niagara seeking British protection. The campaign depopulated the area for post-war settlement and opened up the vast Ohio Country, Western Pennsylvania, West Virginia, and Kentucky to post-war settlement. Some scholars argue that it was an attempt to annihilate the Iroquois and describe the expedition as a genocide,[2][4][5] although this term is disputed, and it is not commonly used when discussing the expedition.[6][7] Historian Fred Anderson, describes the expedition as "close to ethnic cleansing" instead.[8] Some historians have also related this campaign to the concept of total war, in the sense that the total destruction of the enemy was on the table.[9] Today this area is the heartland of Upstate New York, with thirty-five monoliths marking the path of Sullivan's troops and the locations of the Iroquois villages they razed dotting the region, having been erected by the New York State Education Department in 1929 to commemorate the 150th anniversary of the expedition.[10]

Overview

Led by Major General John Sullivan and Brigadier General James Clinton, the expedition was conducted during the summer of 1779, beginning June 18 when the army marched from Easton, Pennsylvania, to October 3 when it abandoned Fort Sullivan, built at Tioga, to return to George Washington's main camp in New Jersey. While the campaign had only one major battle, at Newtown (since the tribes evacuated ahead of the large military force) along the Chemung River in western New York, the expedition severely damaged the Iroquois nations' economies by burning their crops, villages, and chattels, thus ruining the Iroquois technological infrastructure. With the Haudenosaunee's shelter gone and food supplies destroyed, the strength of the Iroquois Confederacy was broken. The death toll from exposure and starvation dwarfed the casualties received in the Battle of Newtown, in which an army of 3,200 Continental soldiers decisively defeated about 600 Iroquois and Loyalists.[11] The deaths in this battle were 11 Continental soldiers, 12 Iroquois, and 5 British soldiers.[12]

In response to 1778 attacks by Iroquois and Loyalists on American settlements, such as on Cobleskill, Wyoming Valley and Cherry Valley, Sullivan's army carried out a scorched earth campaign to put an end to Loyalist and Iroquois attacks. The American force methodically destroyed at least forty Iroquois villages throughout the Finger Lakes region of western New York. The survivors fled to British regions in Canada and the Niagara Falls and Buffalo areas.[13] The devastation created great hardships for the thousands of Iroquois refugees who fled the region to shelter under British military protection outside Fort Niagara that winter, and many starved or froze to death, despite strenuous attempts by the British authorities to supply food and provide shelter via their limited resources.[11]

Background

When the American Revolutionary War began, British officials, as well as the colonial Continental Congress, sought the allegiance (or at least the neutrality) of the influential Iroquois Confederacy. The Six Nations divided over what course to pursue. Most Mohawks, Cayugas, Onondagas, and Senecas chose to ally themselves with the British. But the Oneidas and Tuscaroras, thanks in part to the influence of Presbyterian missionary Samuel Kirkland, joined the American revolutionaries. For the Iroquois, the American Revolution became a civil war.

The Iroquois homeland lay on the frontier between the Province of Quebec and the provinces of New York and Pennsylvania. After a British army surrendered after the Battles of Saratoga in upstate New York in 1777, Loyalists and their Iroquois allies raided American Patriot settlements in the region, as well as the villages of American-allied Iroquois. Working out of Fort Niagara, men such as Loyalist commander Major John Butler, Sayenqueraghta, Mohawk military leader Joseph Brant, and Seneca chief Cornplanter led the British-Indian raids. Commander-in-chief General George Washington never allocated more than minimal Continental Army troops for the defense of the frontier, and he told the frontier settlements to use local militia for their defense.

On June 10, 1778, the Board of War of the Continental Congress concluded that a major Indian war was in the offing. Since a defensive war would prove inadequate, the board called for a major expedition of 3,000 men against Fort Detroit and a similar thrust into Seneca country to punish the Iroquois. Congress designated Major General Horatio Gates to lead the campaign and appropriated funds for the campaign.[14] Despite these plans, the expedition did not occur until the following year.

On July 3, 1778, Loyalist commander Major Butler led his Rangers accompanied by a force of Senecas and Cayugas (led by Sayenqueraghta) in an attack on Pennsylvania's Wyoming Valley (a rebel granary and settlement along the Susquehanna River near Wilkes-Barre). About 300 of the approximately 375 armed Patriot defenders were killed at the Battle of Wyoming, after which houses, barns, and mills were burned throughout the valley.[15][16]

In September 1778, revenge for the Wyoming defeat was taken by American Colonel Thomas Hartley who, with 200 soldiers, burned nine to twelve Seneca, Delaware, and Mingo villages along the Susquehanna River in northeastern Pennsylvania, including Tioga and Chemung. At the same time, Joseph Brant led an attack on German Flatts in the Mohawk Valley, destroying all the houses and fields in the area. Further American retaliation was soon taken by Continental Army units under William Butler (no relation to John Butler) and John Cantine, burning the substantial Indian villages at Unadilla and Onaquaga on the Susquehanna River.

On November 11, 1778, Loyalist Captain Walter Butler (the son of John Butler) led two companies of Butler's Rangers along with about 320 Iroquois led by Cornplanter, including 30 Mohawks led by Joseph Brant, on an assault at Cherry Valley in New York. While the fort was surrounded, Indians began to massacre civilians in the village, killing and scalping 16 soldiers and 32 civilians, mostly women and children, and taking 80 captives, half of whom were never returned. The town was plundered and destroyed. Over a year, Butler's Rangers and their Iroquois allies had reduced much of upstate New York and northeastern Pennsylvania to ruins, causing thousands of farmers to flee and depriving the Continental Army of food.[17]

The Cherry Valley Massacre convinced the American colonists that they needed to take action. In April 1779, American Colonel Van Schaick led an expedition of over 500 soldiers against the Onondaga, destroying several villages.[18] When the British began to concentrate their military efforts on the southern colonies in 1779, Washington used the opportunity to launch a larger planned offensive towards Fort Niagara. His initial impulse was to assign the expedition to Major General Charles Lee. Still, he, Major General Philip Schuyler, and Major General Israel Putnam were all disregarded for various reasons. Washington first offered command of the expedition to Horatio Gates, the "Hero of Saratoga," but Gates turned down the offer, ostensibly for health reasons. Major General John Sullivan, fifth on the seniority list, was offered command on March 6, 1779, and accepted. Washington's orders to Sullivan were:

Orders of George Washington to General John Sullivan, at Head-Quarters (Wallace House, New Jersey) May 31, 1779

- The Expedition you are appointed to command is to be directed against the hostile tribes of the Six Nations of Indians, with their associates and adherents. The immediate objects are the total destruction and devastation of their settlements, and the capture of as many prisoners of every age and sex as possible. It will be essential to ruin their crops now in the ground and prevent their planting more.

- I would recommend, that some post in the center of the Indian Country, should be occupied with all expedition, with a sufficient quantity of provisions whence parties should be detached to lay waste all the settlements around, with instructions to do it in the most effectual manner, that the country may not be merely overrun, but destroyed.

- But you will not by any means listen to any overture of peace before the total ruinment of their settlements is effected. Our future security will be in their inability to injure us and in the terror with which the severity of the chastisement they receive will inspire them.[19]

Expedition

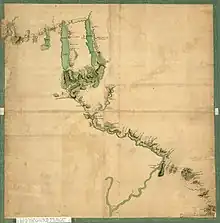

Washington instructed Gen. Sullivan and three brigades, including Morgan's Riflemen and one of the brigades consisting of General Edward Hand's "Light Corps", to march from Easton, Pennsylvania to the Susquehanna River in central Pennsylvania and to follow the river upstream to Tioga, now known as Athens, Pennsylvania. He ordered Gen. James Clinton to assemble a fourth brigade at Schenectady, New York, move westward up the Mohawk River Valley to Canajoharie, and cross overland to Otsego Lake as a staging point. When Sullivan ordered, Clinton's New York Brigade was to march down the Susquehanna to meet Sullivan at Tioga, destroying all Indian villages on his route. Sullivan's army was to have totaled 15 regiments and 5,000 men, but his Pennsylvania brigade entered the campaign more than 750 men short and promised enlistments never materialized. In addition, the third regiment of the brigade, the German Battalion, had shrunk by casualties, sickness, and desertion (the three-year term of enlistment of its soldiers had expired on June 27) to only 100 men and was parceled out in 25-man companies as flank protection for the expedition. Armand's Legion was recalled by Washington to the Main Army before the campaign began. Because of these and other shortages, Sullivan's army, including two companies of local militia totaling only 70 men, never exceeded 4,000 troops.

The main army left Easton on June 18, marching 58 miles to an encampment on the Bullock farm in the Wyoming Valley, which it reached on June 23. There they awaited provisions and supplies that had not been sent forward, remaining in the Wyoming Valley until July 31. The army marched slowly, paced by both the mountainous terrain and the flatboats carrying the army's supplies up the Susquehanna, and arrived at Tioga on August 11. They began construction of a temporary fort at the confluence of the Chemung and Susquehanna Rivers they called Fort Sullivan.

Sullivan sent one of his guides, Lt. John Jenkins, who had been captured while surveying the area in November 1777, with a scouting party to reconnoiter Chemung. He reported that the village was active and unaware of his presence. Sullivan marched the greater part of the army all night over two high defiles and attacked out of a thick fog just after dawn, only to find the town deserted. Brig. Gen. Edward Hand reported a small force fleeing towards Newtown and received permission to pursue it. Despite flankers, he had gone only a mile when his advance guard was ambushed, with six dead and nine wounded.[20] The entire brigade assaulted, but the ambushers escaped with minimal casualties. Sullivan's men spent the day burning the town and destroying its grain and vegetable crops. During the afternoon, the 1st New Hampshire Regiment of Poor's brigade was fired on, either from ambush or possibly by fire from other troops,[21] inflicting another soldier killed and five wounded.[22] Ambushes also occurred on August 15 and 17,[23] with combined casualties of two killed and two wounded. On August 23, the accidental discharge of a rifle in camp resulted in one captain killed and one man wounded.[23]

After two-weeks' portage of supplies, Clinton's brigade set up camp on June 30 at the south end of Otsego Lake (now Cooperstown, New York), where he waited for orders that did not arrive until August 6. The next day he began his destructive march of 154 miles (248 km) to Tioga along the upper Susquehanna, taking all of his supplies with him in 250 bateaux. The actions at Chemung made Sullivan suspicious that the Iroquois might be trying to defeat in detail his split forces, and the next day he sent 1,084 picked men under Brig. Gen. Enoch Poor north to locate Clinton and escort him to Fort Sullivan. The entire army assembled on August 22.

On August 26, the combined army of approximately 3,200 men and 250 pack horse teamsters left Fort Sullivan, garrisoned by 300 troops taken from across the army and left behind under Col. Israel Shreve of the 2nd New Jersey Regiment. Marching slowly north into the Six Nations territory in central western New York, the campaign had only one major battle, the Battle of Newtown, fought on August 29. It was a complete victory for the Continental Army. Later a 25-man detachment of the Continental Army was ambushed, and all but five were captured and killed at the Boyd and Parker ambush. On September 1, Captain John Combs died of an illness.[24]

Sullivan's forces reached their deepest penetration at the Seneca town of Chenussio (also called Little Beard's town, Beardstown, Chinefee, Genesee, and Geneseo), near the present Cuylerville, New York, on September 15, inflicting destruction on the Iroquois villages before returning to Fort Sullivan at the end of the month. Three days later, the army abandoned the fort to return to Morristown, New Jersey, and go into winter quarters. By Sullivan's account, forty Iroquois villages were destroyed, including Catherine's Town, Goiogouen, Chonodote, and Kanadaseaga, along with all the crops and orchards of the Iroquois.

Immediately before the expedition, the Seneca war chief Sayenqueraghta gave a speech at Fort Niagara urging the Wyandot people to support "the King, our Father" and assist in the resistance against the Continental Army. Otherwise, he stated, "we must be a miserable People, and be left exposed to the Resentment of the Rebels, who, notwithstanding their fair Speeches, wish for nothing more, than to extirpate us from the Earth, that they may possess our Lands." Later, when the invasion was already in progress, Mohawk military leader Joseph Brant warned that the Patriots, whom he called "Bostonians", sought to commit genocide against the Iroquois, saying "their intention is to exterminate the People of the Long House."[4]

Appointed the British governor of Quebec in 1778, Frederick Haldimand, while kept informed of Sullivan's invasion by Butler and Fort Niagara, did not supply sufficient troops for his Iroquois allies' defense. Late in September, he dispatched a force of about 600 Loyalists and Iroquois, but by then, the expedition had successfully ended.

Brodhead's expedition

Further west, a concurrent expedition was undertaken by Colonel Daniel Brodhead. Brodhead left Fort Pitt on August 14, 1779, with a contingent of 600 men, regulars of his 8th Pennsylvania Regiment and militia, marching up the Allegheny River into the Seneca and Lenape country of northwestern Pennsylvania and southwestern New York. Since most native warriors were away to confront Sullivan's army, Brodhead met little resistance and destroyed about ten villages, including Conewango. Although initial plans called for Brodhead to eventually link up with Sullivan at Chenussio for an attack against Fort Niagara, Brodhead turned back after destroying villages near modern-day Salamanca, New York, never linking up with the main force. Washington's letters indicate that the cross-country trek east to the Finger Lakes region was considered too dangerous, limiting this minor expedition to a raid north.

Teantontalago

The final operation of the campaign occurred on September 27. Sullivan sent a portion of Clinton's brigade directly back to winter quarters by way of Fort Stanwix, under Colonel Peter Gansevoort of the 3rd New York Regiment. Two days after leaving Stanwix, near their origination point of Schenectady, the detachment stopped at Teantontalago, the "Lower Mohawk Castle" (also known as Thienderego, Tionondorage, and Tiononderoga) and carried out orders to arrest every male Mohawk. Gansevoort wrote, "It is remarked that the Indians live much better than most of the Mohawk River farmers, their houses [being] very well furnished with all [the] necessary household utensils, great plenty of grain, several horses, cows, and wagons". The male population was incarcerated at Albany until 1780 and then released.

The action dispossessed the Mohawks of their homes. Local white settlers, homeless after the Iroquois raids, asked Gansevoort to turn the homes over to them. Both actions were criticized by Philip Schuyler, then a New York representative to the Continental Congress, because all the Mohawks of Lower Mohawk castle had rejected fighting with the British, and many supported the Patriot cause. Ironically, Schuyler had been Washington's preference for command of the expedition. Still, his relief of command of the Continental Army's Northern Department had led to private service with the army until he could resign his commission, which he did in April 1779.

Horseheads

Exhausted from carrying heavy military equipment, Sullivan's horses reached the end of their endurance on their return home. Just north of Elmira, New York, Sullivan euthanized his pack horses. A few years later, the skulls of these horses were lined along the trail as a warning to settlers. The area became known as "the Valley of Horses Heads" and is now known as the village and town of Horseheads, New York.[25]

Aftermath

Sullivan, whose illness had slowed the expedition at times, resigned from his commission in 1780 when his health worsened.

More than 5,000 Iroquois refugees fled to the area surrounding the British-held Fort Niagara (modern-day towns of Youngstown and Lewiston, New York), seeking supplies and protection from the British. A report from 1778 by John Butler on the Iroquois: "The Indians in this part of the Country are so ill off for Provisions that many have nothing to subsist upon but the roots and greens they gather in the woods" in May 1778 – i.e., before the expedition.[26] Fearing attack, many Tuscarora and Oneida defected to the British cause.

After the war the British granted the Iroquois 675,000 acres of land in Canada. About 1,450 Iroquois and 400 allies lived at one new reserve at Grand River.[27]

In February 1780, retired General Schuyler, now in the Congress, sent a party of pro-rebellion Indians to Fort Niagara to appeal for peace with the British-allied Iroquois. Suspecting a trick by Schuyler, those Iroquois rejected the proposal. The four messengers were imprisoned, and one of them died.

Despite widespread dispersion, Washington was disappointed by the lack of a decisive battle and the failure to capture Fort Niagara. Although in truth, Washington's guidance to Sullivan had been that he take Ft Niagara, "if possible," an option not easily within Sullivan's means given the limitations of his artillery (no guns bigger than six-inch field howitzers) and his logistics. Iroquois warriors and Loyalists continued to periodically raid the Mohawk and Schoharie Valleys during 1780 and 1781, causing widespread devastation of property and crops and killing more than 200 settlers. The last significant raid devastated a 20-mile swath of the lower Mohawk Valley in October 1781 but was defeated at the Battle of Johnstown on October 25, 1781. Walter Butler was killed in battle on October 30 at West Canada Creek during the Tory retreat.

Results

The campaign devastated the Iroquois' towns and infrastructure. In the long term, it became clear that the expedition broke the Iroquois Confederacy's power to maintain their former crops and use many of their town locations; the expedition caused the dispersion of the Iroquois people and appeared to have caused a famine among the Iroquois, who had become unable to support themselves or survive during the harsh winter of 1779–1780. Rhiannon Koehler estimates that as many as 55.5% of the population may have perished due to the expedition from starvation and exposure, combined with the direct killings of Iroquois by the Continental Army.[2]

Following the end of the Revolutionary War, much of the Iroquois land was secured by the United States government in the Treaty of Fort Stanwix agreed to by the six nations of the Iroquois Confederacy. Treaties later absorbed this land with the State of New York. Much of the native population of these lands would move to Canada, Oklahoma, and Wisconsin. In the wake of the Treaty of Paris that officially ended the Revolutionary War, European Americans began settling the newly vacant areas in relative safety, eventually isolating the remaining pockets of demoralized Iroquois into villages and towns cut off under land treaties with New York State.

The continuing encroachment of American settlers onto Native American lands in the Old Northwest, which had been ceded to the United States by Great Britain following the end of the war, would prompt the formation of the Northwestern Confederacy by the Iroquois and other allied tribes to resist American expansion, which in turn led to further military campaigns against them by the United States during the ensuing Northwest Indian War.[28][4]

Ordering the "particulars of the expedition" would earn General Washington the moniker "The Town Burner" thereafter among the Seneca,[29] though it had also been applied to him decades earlier after his great-grandfather John Washington had been given the nickname by the Susquehannock.[30][31]

See also

- American Revolutionary War § Stalemate in the North. Places ' Sullivan Expedition ' in overall sequence and strategic context.

Footnotes

- 1 2 Soodalter, Ron (July 8, 2011). "Massacre & Retribution: The 1779–80 Sullivan Expedition". World History Group. Retrieved May 17, 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 Koehler, Rhiannon (Fall 2018). "Hostile Nations: Quantifying the Destruction of the Sullivan-Clinton Genocide of 1779". American Indian Quarterly. 42 (4): 427–453. doi:10.5250/amerindiquar.42.4.0427. S2CID 165519714.

- ↑ "A Narrative of the Life of Mrs. Mary Jemison," 1824, James E. Seaver, Canandaigue, NY, p.99

- 1 2 3 Ostler, Jeffrey (October 2015). "'To Extirpate the Indians': An Indigenous Consciousness of Genocide in the Ohio Valley and Lower Great Lakes, 1750s–1810". The William and Mary Quarterly. 72 (4): 587–622. doi:10.5309/willmaryquar.72.4.0587. JSTOR 10.5309/willmaryquar.72.4.0587. S2CID 146642401. Retrieved April 2, 2022.

- ↑ Mann, Barbara Alice (March 30, 2005). George Washington's War on Native America. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger. p. 52. ISBN 978-0275981778.

- ↑ Leader, Matt (September 15, 2019). "Time to change? Effort seeks 'counter marker' for existing Sullivan-Clinton monument in Hemlock park". Livingston County News. Retrieved May 17, 2022.

"I told her I objected to her… titling the counter marker as the Sullivan-Clinton Genocide," said Alden, speaking last week.

- ↑ Birns, Nicholas (2007). "The Unknown War: The Last of the Mohicans and the Effacement of the Seven Years' War in American Historical Myth". James Fenimore Cooper Society – State University of New York at Oneonta. Retrieved May 17, 2022.

The Sullivan expedition and the clearing-out of the Iroquois in central and western New York State—more like the Anglo-Saxons dispatching the Celts—something which more poetic souls still may lament, but which is not commonly called genocide.

- ↑ Anderson, Fred (2004). George Washington Remembers: Reflections on the French and Indian War. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 138. ISBN 978-0-7425-3372-1.

- ↑ "A well-executed failure: the Sullivan campaign against the Iroquois, July–September, 1779". Choice Reviews Online. 35 (01): 35–0457-35-0457. September 1, 1997. doi:10.5860/choice.35-0457. ISSN 0009-4978.

- ↑ Smith, Andrea Lynn; John, Randy A. (2020). "Monuments, Legitimization Ceremonies, and Haudenosaunee Rejection of Sullivan-Clinton Markers". New York History. 101 (2): 343–365. doi:10.1353/nyh.2020.0042. S2CID 229355901. Retrieved April 29, 2022.

- 1 2 Graymont (1972), p. 208.

- ↑ Eckert (1978), p. 444.

- ↑ "The American Revolution". 1759–1796 Guardhouse of the Great Lakes. Old Fort Niagara. Archived from the original on October 12, 2006. Retrieved November 18, 2007.

- ↑ Graymont (1972), p. 167.

- ↑ Mintz, Max M. (1999). Seeds of Empire: The American Revolutionary Conquest of the Iroquois. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 9780814756225.

- ↑ Williams, Glenn F. (2005). Year of the Hangman: George Washington's Campaign against the Iroquois. Yardley, Pennsylvania: Westholme Publishing. ISBN 9781594160134.

- ↑ Paxton, James (2008). Joseph Brant and his world 18th Century Mohawk Warrior and Statesmen. Toronto: James Lormier & Company. p. 45. ISBN 978-1-55277-023-8.

- ↑ History and Culture: "The Van Schaick Expedition April 1779", National Park Service

- ↑ Washington, George (May 31, 1779). "From George Washington to Major General John Sullivan, 31 May 1779". Founders Online, National Archives.

- ↑ Eckert (1978), p. 406.

- ↑ Eckert (1978), pp. 552–553, note 313.

- ↑ Cruikshank (1893), p. 81.

- 1 2 Cook, Frederick (1887). "Journal of Thomas Grant". RootsWeb.com. Knapp, Peck & Thompson. Archived from the original on February 6, 2007. Retrieved November 14, 2007.

- ↑ "Capt. (John?) Combs". USGenNet. Retrieved November 19, 2007.

- ↑ "Village History". Village of Horseheads. Village of Horseheads. Retrieved September 17, 2019.

- ↑ Cruikshank (1893), p. 63.

- ↑ Johansen, Bruce Elliott; Mann, Barbara Alice (2000). Encyclopedia of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois Confederacy). Greenwood. p. 131. ISBN 9780313308802.

- ↑ Ostler, Jeffrey (February 3, 2016). "'Just and lawful war' as genocidal war in the (United States) Northwest Ordinance and Northwest Territory, 1787–1832". Journal of Genocide Research. 18 (1): 1–20. doi:10.1080/14623528.2016.1120460. S2CID 74337505. Retrieved April 2, 2022.

- ↑ Pearsall, Sarah M.S. (May–June 2015). "Madam Sacco: How One Iroquois Woman Survived the American Revolution". Humanities. National Endowment for the Humanities. 36 (3). Retrieved January 10, 2023.

- ↑ Fertig, Anne; Montgomery, Alexandra, eds. (2023). "Conotocarious". The Digital Encyclopedia of George Washington. Mount Vernon Ladies' Association. Retrieved January 10, 2023 – via The Fred W. Smith National Library for the Study of George Washington at Mount Vernon.

- ↑ Gizzard, Jr., Frank E. (2002). George Washington: A Biographical Companion. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. p. 53. ISBN 1-57607-082-4. Retrieved January 10, 2023 – via Google Books.

References

- Boatner, Mark Mayo. Encyclopedia of the American Revolution. New York: McKay, 1966; revised 1974. ISBN 0-8117-0578-1.

- Calloway, Colin G. The American Revolution in Indian Country: Crisis and Diversity in Native American Communities. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 1995. ISBN 0-521-47149-4 (hardback).

- Calloway, Colin G. The Indian World of George Washington: The First President, the First Americans, and the Birth of the Nation. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2017. ISBN 978-0190652166 (hardback).

- Eckert, Allan W. (1978). The Wilderness War. New York: Little Brown & Company. ISBN 0-553-26368-4.

- Cruikshank, Ernest (1893). The Story of Butler's Rangers and the Settlement of Niagara. Tribune Printing House.

- Fischer, Joseph R. A Well-Executed Failure: The Sullivan campaign against the Iroquois, July–September 1779. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 2007. ISBN 978-1-57003-837-2

- Graymont, Barbara (1972). The Iroquois in the American Revolution. Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 0-8156-0083-6.

- Mintz, Max M. Seeds of Empire: The American Revolutionary Conquest of the Iroquois. New York: New York University Press, 1999. ISBN 0-8147-5622-0 (hardcover).

- Taylor, Alan. The Divided Ground. New York: Alfred Knopf, 2006. ISBN 0-679-45471-3 (hardcover)

- Williams, Glenn F. Year of the Hangman: George Washington's Campaign Against the Iroquois. Yardley: Westholme Publishing, 2005. ISBN 1-59416-013-9.

- Journals of the military expedition of Major General John Sullivan against the Six Nations of Indians in 1779