The Sullivan Line originally marked in 1816 forms three quarters of the border between Missouri and Iowa and an extension of it forms the remainder. The line was initially created to establish the limits of Native American territory (they would not be permitted south of it); disputes over the boundary were to erupt into the Honey War.

Area prior to Sullivan's Survey

In 1804, in the Treaty of St. Louis the Sac and Fox ceded Missouri north of the Gasconade River (but not their villages on the Mississippi River near Keokuk, Iowa). In 1808, in the Treaty of Fort Clark, the Osage Nation ceded all of Missouri and Arkansas west of the fort (now called Fort Osage in Jackson County, Missouri). The exact boundaries of the treaties were never formally surveyed. Resentments about the treaties caused many members of the tribe to side with the British in the War of 1812. At the conclusion of the war, the tribes in the 1815 Treaties of Portage des Sioux reaffirmed the earlier treaties.

Sullivan's survey

In 1816, surveyor John C. Sullivan was instructed to survey the Osage territory starting 20 WEST of Fort Clark at the Kansas River and Missouri River confluence. From the north bank of the river opposite Kaw Point in what is today Kansas City Downtown Airport he was instructed to survey a line 100 miles (160 km) straight north and then east to the Des Moines River (the Sac and Fox owned the land east of the river). Sullivan's line going north (the Indian Boundary Line (1816)) was to ultimately form the longitudinal line from Iowa to Texas west of which Native Americans were to be removed in the Indian Removal Act of 1830.

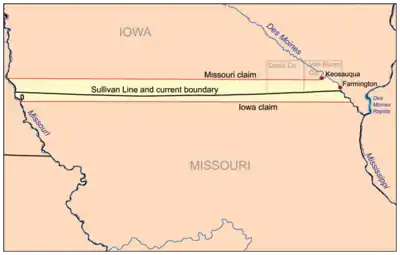

The beginning point, also known as "the old northwest corner of Missouri" at the western end of the Sullivan Line is north of Sheridan, Missouri, at north latitude 40.5710859.[1] Despite his intention to draw the border straight east, he drifted north to about 40.6135698 at the boundary's eastern terminus just south of what is now Farmington, Iowa. This drift of 2.9 miles (4.7 km) northward is generally thought to be due to the change in magnetic declination, for which he did not correct his compass as the survey progressed.

Use as interstate boundary

When Missouri prepared to enter the Union in 1820, various boundaries were discussed before it was finally decided to go with a boundary that had already been formally surveyed, so the Sullivan line was picked. However the Missouri Constitution muddied the debate with phrase: "to the intersection of the parallel of latitude which passes through the rapids of the River Des Moines". As it happened, there were no rapids where Sullivan came to the Des Moines River. However, the Des Moines Rapids on the Mississippi River were just 15 miles (24 km) in a straight line east of Sullivan's eastern terminus.

In the Indian Removal Act of 1830, Sullivan's lines were used for the removal of almost all Native Americans from the eastern portion of the United States (in such events as the Trail of Tears). In 1832, at the conclusion of the Black Hawk War, the Sac and Fox conceded the eastern section of Iowa and the western section of Illinois. In the terms the 12-mile (19 km) stretch between the end of the Sullivan Line and the Mississippi was conceded (in what was called Half Breed Tract because it was to be set aside for mixed race residents). In 1836, the western boundary of the Sullivan Line latitude was extended 45 miles (72 km) west to the Missouri River just south of Hamburg, Iowa when the federal government relocated the already relocated tribes further west in the Platte Purchase. The land was annexed to Missouri.

The western extension did not have the same quirks as the first survey since the solar compass had made it easier to make accurate east–west surveys. However the quirks of the eastern portion of the Sullivan Line were to stir passions as Iowa prepared to enter the Union. Missouri, citing evidence from surveyor Joseph C. Brown, who had established the meridian grid for the Louisiana Purchase, said using the Kaw Point starting point was invalid and that the survey should have been based on the mouth of the Ohio River. Using that calculation, he said that Missouri's border should extend about 9.5 miles (15.3 km) even further into Iowa (with the town of Keosauqua, Iowa, specifically coming into play).

In 1839, the Clark County, Missouri sheriff went into this new stretch to collect taxes. When the residents of Iowa refused to pay, he is said to have cut down three trees to collect honey bee beehives in lieu of taxes. He was arrested. Residents from both sides threatened to fight, before the governors agreed to let the United States Supreme Court settle the matter.

Also, in 1839, Latter Day Saints followers of Joseph Smith, regrouped at Nauvoo, Illinois, on the Mississippi River after having been kicked out of Missouri in the Mormon War. Nauvoo lies in a straight line with the Sullivan Line. In 1844 after Smith was killed, his followers began their trek west that was to ultimately lead them to Utah. The first Iowa leg of the trail is just north of the Sullivan Line.

Retracement Surveys

In 1849, the Supreme Court ruled that the Sullivan line was the boundary,[2] since it had been written into the Missouri Constitution and ordered it resurveyed. Commissioners Hendershot and Minor reported in 1850 they found many of the original 1816 markings in their survey. They set cast iron monuments at the initial point on the boundary and every 10 miles (16 km) along it as well as more frequent markings.[3][4]

A dispute in the late 1800s caused a portion of the line near Decatur County Iowa to be surveyed and re-marked with granite monuments every mile for 20 miles (32 km). In 2005 the State of Missouri contracted a resurvey of the border, locating the markers from the Supreme Court survey of 1850 and those added in the 1890s.[5]

See also

References

- ↑ Derived from data obtained from Missouri DNR, 2006.

- ↑ Supreme Court Case decision

- ↑ US Supreme Court reports, 1851

- ↑ J.S. Dodds, Original Instructions Governing Public Land Surveys of Iowa, Chap. VII

- ↑ Troy Hayes, Missouri-Iowa Boundary Line Investigation - The American Surveyor - March-April 2006