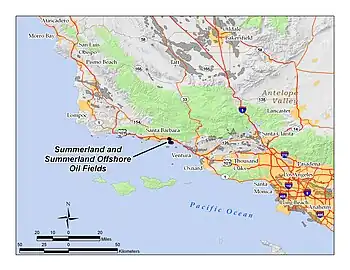

The Summerland Oil Field (and Summerland Offshore Oil Field) is an inactive oil field in Santa Barbara County, California, about four miles (6 km) east of the city of Santa Barbara, within and next to the unincorporated community of Summerland. First developed in the 1890s, and richly productive in the early 20th century, the Summerland Oil Field was the location of the world's first offshore oil wells, drilled from piers in 1896.[1][2] This field, which was the first significant field to be developed in Santa Barbara County,[3] produced 3.18 million of barrels of oil during its 50-year lifespan, finally being abandoned in 1939-40.[4] Another nearby oil field entirely offshore, discovered in 1957 and named the Summerland Offshore Oil Field, produced from two drilling platforms in the Santa Barbara Channel before being abandoned in 1996.[5]

Setting

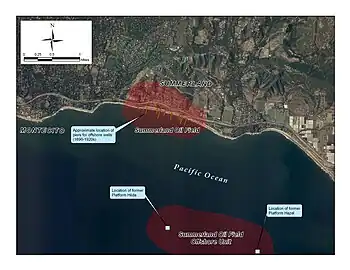

The formerly productive region of the Summerland Oil Field is on the coast of southern Santa Barbara County, about four miles (6 km) east of the city of Santa Barbara, and includes most of the town of Summerland, as well as adjacent parts of Montecito. It covers an area of a bit more than a square mile – 740 acres (3.0 km2) – of which 380, a little more than half, is onshore.[6]

The climate is Mediterranean, with an equable temperature regime year-round, and most of the precipitation falling between October and April in the form of rain. Freezes are rare. Runoff is towards the ocean. Bluffs rise sharply behind the beach, but rather than having an extended plateau behind the bluffs, as is the case along much of the south coast of Santa Barbara County, the land rises with a moderate slope towards the Santa Ynez Mountains. The town of Summerland is built on the coast-facing part of this hillside, taking advantage of the ocean view, with modern residential and commercial development covering long-abandoned oil wells. The offshore part of the main Summerland field was in shallow water adjacent to the beach, and was drilled from piers. A popular beach extends the length of the former oil field, immediately below the town, and a park – Lookout Park – sits atop the bluffs.

Summerland Offshore Oil Field is a separate field in the Santa Barbara Channel about one and a half miles offshore, but within the 3-mile limit inside of which oil leasing is subject to state rather than federal regulation. Two oil platforms, named Hilda and Hazel, formerly stood on this field; Chevron Corp. dismantled them in 1996 and production from this field ended.[5] The Carpinteria Offshore Oil Field, about four miles (6 km) to the southeast, also once contained a pair of platforms dismantled that same year, and its three remaining platforms outside the 3-mile (4.8 km) limit are visible from the shore at Summerland.

Geology

The Summerland field is contained in a series of sedimentary rock units in a trough known as the Carpinteria Basin.[7] Oil is trapped in the Pleistocene-age Casitas Formation underneath impermeable sediments, although petroleum regularly makes its way to the surface in the form of asphalt seeps, here as elsewhere on the south coast of Santa Barbara County. Another unit underneath the Casitas Formation, the Oligocene-age Vaqueros Sandstone, also has considerable quantities of petroleum, with the capping unit being the impermeable Miocene-age Rincon Formation.[8]

Oil in the Casitas Formation is shallow, at an average depth of only 140 feet (43 m), accounting for its early discovery and easy exploitation. In the Vaqueros formation the average depth to oil is 1,400 feet (430 m) in the main Summerland field, and 7,000 feet (2,100 m) in the Summerland Offshore field.[9]

History, operations, and production

Oil and asphalt seeps in the vicinity of the Summerland field were known since prehistoric times, as the native Chumash peoples used tar from this spot and other similar seeps as sealant for their tomols, the watercraft with which they skilfully navigated the Santa Barbara Channel. Sometime before 1894, enterprising petroleum prospectors recognized the likelihood that economically viable deposits of oil and gas were the source for these seeps, and began digging. The first finds of petroleum were extremely heavy oil – API gravity of 7, so essentially asphalt – but undeterred, they continued searching for more marketable oil.[10] The earliest known oil well in the vicinity of Summerland dates from 1886, and was drilled on the side of Ortega Hill, the topographic prominence just west of Summerland. While the well failed to produce marketable quantities of oil, it showed that there were indeed petroleum-bearing strata only several hundred feet below ground surface – well within the reach of late 19th-century drilling technology.[11]

By 1895, wooden derricks had sprouted across the beaches and bluffs of Summerland, completely changing the character of the community. Founded in 1889, originally the town had been a spiritualist community consisting of a cluster of small houses around a central building in which seances were held. H.L. Williams, the founder of the town, had sold lots for $25 each, bringing in many people from outside of the area to build small houses. Within a few years, those same lots were commanding prices up to $7,500 because of the seemingly unlimited quantities of oil that could be drawn from the ground.[12] Prospectors recognized that the tar sheen in the surf, along with evidence of natural gas venting, indicated that the oil field extended offshore; they then began drilling not just on the beach but from piers through the shallow water into the sub-marine sediments. Drilled in 1896, these were the world's first offshore oil wells.[1][12][13][14]

Seeing that the Southern Pacific Railroad line ran along the blufftop through the oil field, John Treadwell, a mining engineer with that company, decided to try to power locomotives with the heavy oil from the field rather than coal, and to help with this enterprise built the largest of the wharves out into the ocean. Named the Treadwell Wharf, in 1900 this structure alone had 19 wells along its length, which reached 1,230 feet (370 m) by 75 feet (23 m) wide. Summerland thereby became a convenient refueling stop for the trains running between the coastal cities. The train line was new then; the tracks between Santa Barbara and Los Angeles were only built in 1887, and the line did not reach San Francisco until 1901, around the time production was peaking at Summerland.[7]

.jpg.webp)

Development of the Summerland Field was not entirely without controversy, even in its earliest years. The boom from the first oil find was so spectacular that after the hundreds of wells already put in had begun to run dry, drillers attempted to expand their area of operations uncomfortably close to Santa Barbara. In the late 1890s, a crowd of vigilantes headed by Reginald Fernald, a local newspaper publisher, tore down a drilling rig erected on Miramar Beach itself (now adjacent to a luxury hotel).[15]

The Summerland field had an early peak in production followed by a precipitous decline. A severe winter storm in 1903 destroyed many of the flimsy wooden derricks on the wharves and beach, and by 1906 most of the oil production had ended, leaving behind abandoned derricks, many of which stood for decades.[7] Drillers discovered a new deeper pool in the field in 1929, in the Vaqueros Sandstone, at a depth of about 1,400 feet (430 m), but the wells at that time were less numerous and obtrusive. Also in 1929, the Mesa Oil Field was discovered, just about six miles (10 km) to the west of the Summerland field and within the city of Santa Barbara itself; the Vaqueros Sandstone was the oil-bearing unit there as well. Peak annual production for the onshore part of the Summerland field was actually in 1929, at 118,519 barrels, from the Vaqueros, but this too was soon exhausted.[10] Production in the field ceased entirely in 1939, and the remaining abandoned structures – wharves and derricks and associated equipment – were removed.[10][12] During the entire period of operation of the field, over 412 oil wells were drilled.[7]

Summerland Offshore Oil Field

The Summerland Offshore Oil Field – distinct from the offshore portion of the main Summerland field, as it was more than a mile from shore – was not discovered until 1957. Its oil was from the same source rock as the deeper pool of the onshore field, the Vaqueros Sandstone, but the API gravity of the oil was lower (35) allowing it to flow freely.[16] This field was drilled from two oil platforms, Hilda and Hazel, erected in 1958 and 1960 respectively. Platform Hazel was the first platform in California to be constructed onshore and towed to the site by barges. Both were anchored to the sea floor, which was approximately 100 feet (30 m) underneath each platform.[5] They produced a cumulative total of 27.6 million barrels of oil and 97.8 million cubic feet of natural gas before being demolished in 1996.[5] Peak production from the Summerland Offshore field was in 1964, at almost 3.8 million barrels, but the cost to maintain the operation, combined with the diminishing returns from the field, and public sentiment opposing drilling in the Santa Barbara Channel – as these platforms were close to the site of the notorious 1969 oil spill – led their operator, Chevron Corp., to shut them down.[5][16]

While neither field is producing in the present day, periodic attempts have been made to find and cap leaking wells from the operations in the late 19th and early 20th century. In those early years of the petroleum industry, there was little to no regulation of operating practice, and abandoned wells were often filled with whatever was available – earth, wooden poles, old mattresses and other rubbish were commonly stuffed down the holes, but these methods are ineffective for long-term plugging of an oil well.[7] Since petroleum migrates upwards from pressurized source regions, over time it will find any open pathways to the surface; in the case of natural gas, this can cause an explosion hazard. Modern well abandonment techniques involve cutting off a well casing well below ground surface and capping with concrete, forming a permanent seal. Between 1960 and 1968, eighty old wells were located and capped in an attempt to stop the slow leaking of oil into the ocean. More wells were located, cut, filled, and capped in 1975 and 1993.[7]

References

- 1 2 Wilder, Robert J. (1998). Listening to the sea: the politics of improving environmental protection. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 30. ISBN 0-8229-5663-2.

- ↑ California Department of Conservation, Division of Oil, Gas, and Geothermal Resources (DOGGR). California Oil and Gas Fields, Volumes I, II and III. Vol. I (1998), Vol. II (1992), Vol. III (1982). p. 681. PDF file available on CD from www.consrv.ca.gov.

- ↑ Eric R.A.N. Smith, Energy, the environment, and public opinion, p. 14. Rowman & Littlefield, 2002. ISBN 0-7425-1026-3

- ↑ Dibblee, Thomas. Geology of the central Santa Ynez Mountains, Santa Barbara County, California. Bulletin 186, California Division of Mines and Geology. San Francisco, 1966.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Basavalinganadoddi, Chandrashekar; Paul B. Mount II (2004). "Abandonment of Chevron Platforms Hazel, Hilda, Hope and Heidi" (PDF). Proceedings of the Fourteenth (2004) Annual International Offshore and Polar Engineering Conference. Toulon, France. p. 468. Retrieved November 29, 2009.

- ↑ DOGGR, pp. 534-536

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Ira Leifer et al., "Oil emissions from nearshore and onshore Summerland: Final Report." OSPR Technical Publication No. 07- 001. State of California Department of Fish and Game - Office of Spill Prevention and Response. 1700 K St., Sacramento, Calif. 95814.

- ↑ DOGGR, p. 534-536

- ↑ DOGGR, p. 678-679

- 1 2 3 DOGGR, p. 536

- ↑ Prutzman, Paul W. (1913). Petroleum in Southern California. Sacramento, California: California State Mining Bureau. p. 406.

- 1 2 3 Baker, Gayle (2003). Santa Barbara: Another Harbor Town History. Santa Barbara, California: Harbor Town Histories. p. 63. ISBN 0-9710984-1-7.

- ↑ Tompkins, Walker A. (1975). Santa Barbara, Past and Present. Santa Barbara, California: Tecolote Books. p. 80.

- ↑ DOGGR, p. 681

- ↑ Tompkins, Walker A. (1975). Santa Barbara, Past and Present. Santa Barbara, California: Tecolote Books. p. 80.

- 1 2 DOGGR, p. 679