In technical applications of 3D computer graphics (CAx) such as computer-aided design and computer-aided manufacturing, surfaces are one way of representing objects. The other ways are wireframe (lines and curves) and solids. Point clouds are also sometimes used as temporary ways to represent an object, with the goal of using the points to create one or more of the three permanent representations.

Open and closed surfaces

If one considers a local parametrization of a surface:

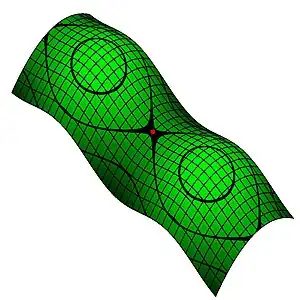

then the curves obtained by varying u while keeping v fixed are coordinate lines, sometimes called the u flow lines. The curves obtained by varying v while u is fixed are called the v flow lines. These are generalizations of the x and y Cartesian coordinate lines in the plane coordinate system and of the meridians and circles of latitude on a spherical coordinate system.

Open surfaces are not closed in either direction. This means moving in any direction along the surface will cause an observer to hit the edge of the surface. The top of a car hood is an example of a surface open in both directions.

Surfaces closed in one direction include a cylinder, cone, and hemisphere. Depending on the direction of travel, an observer on the surface may hit a boundary on such a surface or travel forever.

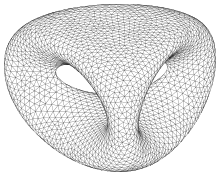

Surfaces closed in both directions include a sphere and a torus. Moving in any direction on such surfaces will cause the observer to travel forever without hitting an edge.

Places where two boundaries overlap (except at a point) are called a seam. For example, if one imagines a cylinder made from a sheet of paper rolled up and taped together at the edges, the boundaries where it is taped together are called the seam.

Flattening a surface

Some open surfaces and surfaces closed in one direction may be flattened into a plane without deformation of the surface. For example, a cylinder can be flattened into a rectangular area without distorting the surface distance between surface features (except for those distances across the split created by opening up the cylinder). A cone may also be so flattened. Such surfaces are linear in one direction and curved in the other (surfaces linear in both directions were flat to begin with). Sheet metal surfaces which have flat patterns can be manufactured by stamping a flat version, then bending them into the proper shape, such as with rollers. This is a relatively inexpensive process.

Other open surfaces and surfaces closed in one direction, and all surfaces closed in both directions, can't be flattened without deformation. A hemisphere or sphere, for example, can't. Such surfaces are curved in both directions. This is why maps of the Earth are distorted. The larger the area the map represents, the greater the distortion. Sheet metal surfaces which lack a flat pattern must be manufactured by stamping using 3D dies (sometimes requiring multiple dies with different draw depths and/or draw directions), which tend to be more expensive.

Regions

Patches

A surface may be composed of one or more patches, where each patch has its own U-V coordinate system. These surface patches are analogous to the multiple polynomial arcs used to build a spline. They allow more complex surfaces to be represented by a series of relatively simple equation sets rather than a single set of complex equations. Thus, the complexity of operations such as surface intersections can be reduced to a series of patch intersections.

Surfaces closed in one or two directions frequently must also be broken into two or more surface patches by the software.

Faces

Surfaces and surface patches can only be trimmed at U and V flow lines. To overcome this severe limitation, surface faces allow a surface to be limited to a series of boundaries projected onto the surface in any orientation, so long as those boundaries are collectively closed. For example, trimming a cylinder at an angle would require such a surface face.

A single surface face may span multiple surface patches on a single surface, but can't span multiple surfaces.

Planar faces are similar to surface faces, but are limited by a collectively closed series of boundaries projected to an infinite plane, instead of a surface.

Skins and volumes

As with surfaces, surface faces closed in one or two directions frequently must also be broken into two or more surface faces by the software. To combine them back into a single entity, a skin or volume is created. A skin is an open collection of faces and a volume is a closed set. The constituent faces may have the same support surface or face or may have different supports.

Solids

Volumes can be filled in to build a solid model (possibly with other volumes subtracted from the interior). Skins and faces can also be offset to create solids of uniform thickness.

Continuity

A surface's patches and the faces built on that surface typically have point continuity (no gaps) and tangent continuity (no sharp angles). Curvature continuity (no sharp radius changes) may or may not be maintained.

Skins and volumes, however, typically only have point continuity. Sharp angles between faces built on different supports (planes or surfaces) are common.

Visualization and display

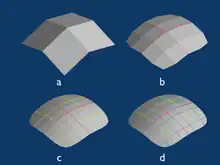

Surfaces may be displayed in many ways:

- Wireframe mode. In this representation the surface is drawn as a series of lines and curves, without hidden-line removal. The boundaries and flow lines (isoparametric curves) may each be shown as solid or dashed curves. The advantage of this representation is that a great deal of geometry may be displayed and rotated on the screen with no delay needed for graphics processing.

wireframe

wireframe

hidden edges wireframe

wireframe

uv isolines

- Faceted mode. In this mode each surface is drawn as a series of planar regions, usually rectangles. Hidden-line removal is typically used with such a representation. Static hidden-line removal does not update which lines are hidden during rotation, but only once the screen is refreshed. Dynamic hidden-line removal continuously updates which curves are hidden during rotations.

Facet wireframe

Facet wireframe Facet shaded

Facet shaded

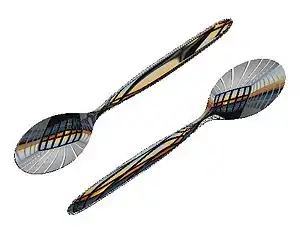

- Shaded mode. Shading can then be added to the facets, possibly with blending between the regions for a smoother display. Shading can also be static or dynamic. A lower quality of shading is typically used for dynamic shading, while high quality shading, with multiple light sources, textures, etc., requires a delay for rendering.

shaded

shaded reflection lines

reflection lines reflected image

reflected image

CAD/CAM representation

CAD/CAM systems use primarily two types of surfaces:

- Regular (or canonical) surfaces include surfaces of revolution such as cylinders, cones, spheres, and tori, and ruled surfaces (linear in one direction) such as surfaces of extrusion.

- Freeform surfaces (usually NURBS) allow more complex shapes to be represented via freeform surface modeling.[1]

Other surface forms such as facet and voxel are also used in a few specific applications.

CAE/FEA representation

In computer-aided engineering and finite element analysis, an object may be represented by a surface mesh of node points connected by triangles or quadrilaterals (polygon mesh). More accurate, but also far more CPU-intensive, results can be obtained by using a solid mesh. The process of creating a mesh is called tessellation. Once tessellated, the mesh can be subjected to simulated stresses, strains, temperature differences, etc., to see how those changes propagate from node point to node point throughout the mesh.

VR/computer animation

In virtual reality and computer animation, an object may also be represented by a surface mesh of node points connected by triangles or quadrilaterals. If the goal is only to represent the visible portion of an object (and not show changes to the object) a solid mesh serves no purpose, for this application. The triangles or quadrilaterals can each be shaded differently depending on their orientation toward the light sources and/or viewer. This will give a rather faceted appearance, so an additional step is frequently added where the shading of adjacent regions is blended to provide smooth shading. There are several methods for performing this blending.

See also

References

- ↑ Piegl, Les; Tiller, Wayne (1997). The NURBS Book (2. ed.). Berlin: Springer. ISBN 3-540-61545-8.