Surgical planning is the preoperative method of pre-visualising a surgical intervention, in order to predefine the surgical steps and furthermore the bone segment navigation in the context of computer-assisted surgery.[1] The surgical planning is most important in neurosurgery and oral and maxillofacial surgery. The transfer of the surgical planning to the patient is generally made using a medical navigation system.

Principles of surgical planning

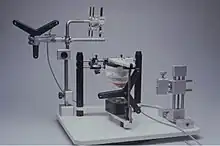

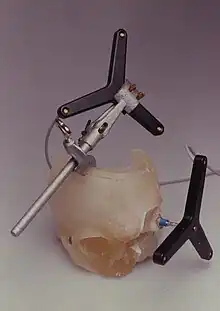

The imagistic dataset used for surgical planning is mainly based on a CT or MRI. In oral and maxillofacial surgery, a different, more "traditional" surgical planning can be used for orthognatic surgery, based on cast models fixed into an articulator.

History of the concept

In order to make a surgical planning, one would need a 3D image of the patient. The starting point was made by G. Hounsfield in the 1970s, by using CT in order to record data about the anatomical situation of the patients.[2] In the 1980s, advances were made by the radiologist M. Vannier and his team, by creating the first computed three-dimensional reconstruction from a CT dataset.[3] In the early 1990s, the surgical planning was performed by using stereolithographic models.[4] During the late 1990s, the first full computer-based virtual surgical planning was made for osteotomies, and then transferred to the operating theatre by a navigation system.[5] Currently 3D Printed models are also used to plan a procedure and improve patient outcomes.[6]

The first commercially available neurosurgical planning systems appeared in the 1990s (the StealthStation by Medtronic,[7] the VectorVision by Brainlab[8]). As newer imaging modalities emerged providing increasing anatomical and functional detail for the patient in the 2000s, these surgical planning systems started to incorporate virtual reality technology to facilitate the visualisation and manipulation of the 3D data. One example of such systems is the Dextroscope, manufactured by Volume Interactions Pte Ltd. The Dextroscope is mostly used in the planning of complex neurosurgical procedures.[9][10][11][12]

References

- ↑ "Surgical Planning - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics". www.sciencedirect.com. Retrieved 2020-09-18.

- ↑ Wells PNT: Sir Godfrey Newbold Hounsfield, Biogr. Mems Fell. R. Soc. 51, 221-235, 2005

- ↑ Vannier MW, Marsh JL, Warren JO (1984). "Three Dimensional CT Reconstruction Images for Craniofacial Surgical Planning and Evaluation" (PDF). Radiology. 150 (1): 179–84. doi:10.1148/radiology.150.1.6689758. PMID 6689758.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Klimek L, Klein HM, Schneider W, Mosges R, Schmelzer B, Voy ED (1993). "Stereolithographic modelling for reconstructive head surgery". Acta Oto-Rhino-Laryngologica Belgica. 47 (3): 329–34. PMID 8213143.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Marmulla R, Niederdellmann H (1999). "Surgical Planning of Computer Assisted Repositioning Osteotomies". Plast Reconstr Surg. 104 (4): 938–944. doi:10.1097/00006534-199909020-00007. PMID 10654731.

- ↑ Thomas, D. J.; Azmi, M. A. B. Mohd; Tehrani, Z. (2014-04-01). "3D additive manufacture of oral and maxillofacial surgical models for preoperative planning". The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology. 71 (9): 1643–1651. doi:10.1007/s00170-013-5587-4. ISSN 1433-3015. S2CID 109978006.

- ↑ Smith K R, Frank K J, Bucholz R D (1994). "The NeuroStation--a Highly Accurate, Minimally Invasive Solution to Frameless Stereotactic Neurosurgery". Computerized Medical Imaging and Graphics. 18 (4): 247–56. doi:10.1016/0895-6111(94)90049-3. PMID 7923044.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Vilsmeier, Stefan, and Fotios Nisiropoulos. "Introduction of the Passive Marker Neuronavigation System VectorVision." In Computer-Assisted Neurosurgery, edited by Norihiko Tamaki M.D and Kazumasa Ehara M.D, 23–37. Springer Japan, 1997. doi:10.1007/978-4-431-65889-4_3.

- ↑ Ferroli, Paolo, Giovanni Tringali, Francesco Acerbi, Domenico Aquino, Angelo Franzini, and Giovanni Broggi. "Brain Surgery in a Stereoscopic Virtual Reality Environment: A Single Institution’s Experience with 100 Cases." Neurosurgery 67, no. 3 Suppl Operative (September 2010): ons79–84; discussion ons84. doi:10.1227/01.NEU.0000383133.01993.96

- ↑ Kockro R. A., Serra L., Tseng-Tsai Y., Chan C., Yih-Yian S., Gim-Guan C., Lee E., Hoe L. Y., Hern N., Nowinski W. L. (2000). "Planning and Simulation of Neurosurgery in a Virtual Reality Environment". Neurosurgery. 46 (1): 118–135. doi:10.1093/neurosurgery/46.1.118. PMID 10626943.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Matis Georgios K, Danilo O de, Silva A, Chrysou Olga I, Karanikas Michail, Pelidou Sygkliti-Henrietta, Birbilis Theodossios A, Bernardo Antonio, Stieg Philip (2013). "Virtual Reality Implementation in Neurosurgical Practice: The 'Can't Take My Eyes off You' Effect". Turkish Neurosurgery. 23 (5): 690–91. PMID 24101322.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Robison R. A., Liu C. Y., Apuzzo M. L. J. (2011). "Man, Mind, and Machine: The Past and Future of Virtual Reality Simulation in Neurologic Surgery". World Neurosurgery. 76 (5): 419–30. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2011.07.008. PMID 22152571.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)