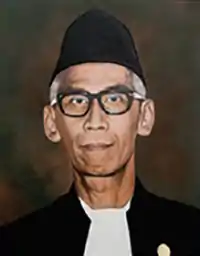

Suryadi | |

|---|---|

| |

| 3rd Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Indonesia | |

| In office 21 June 1966 – August 1968 | |

| Nominated by | Sukarno |

| Preceded by | Wirjono Prodjodikoro |

| Succeeded by | Subekti |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Dutch East Indies |

| Nationality | Indonesian |

Suryadi (sometimes spelled Soerjadi) was a former Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Indonesia, as well as the first chairman of the Indonesian Judges Association.

Career

By 1952, judges on the island of Java had begun to organize; Suryadi had initially been the chairman of the trial court in Semarang at that time.[1] Suryadi was the first chairman of IKAHI, the Judges' Association, at its inception in May 1953.[1][2] He became the first chairman because, during his time as the chairman of the Surabaya district court, he was the first person to organize district judges in 1952.[2] In 1955, he toured the United States and was deeply impressed by the far reach of the Federal judiciary of the United States; his references to the American system were frequent after his return.[3] Additionally, his resentment toward the influence prosecutors increased, and their tendency to cite practices of the judiciary of the Netherlands instead caused clashes of viewpoints.[3]

Suryadi was appointed by the first President of Indonesia, Sukarno, as the third Chief Justice on June 21, 1966.[4] He continued as the Chief Justice throughout the turbulent period known as the Transition to the New Order,[5] and eventually found himself in outright confrontation with the Judges' Association.[6] Like his predecessor Wirjono Prodjodikoro, Suryadi resigned as Chief Justice after a power struggle with the Association's leadership,[7] in part exacerbated due to personal and private disputes with Association members Asikin Kusumah Atmaja and Sri Widoyati Sukito.[8]

The Judges' Association which Suryadi himself helped found was opposed to him, in part, because of perceptions that he was being used by Sukarno; heated personal confrontations had previously taken place when Suryadi had served at the same Jakarta district courts as Atmaja and Sukito due to their impression that he was allowing his politics to interfere with his work.[8] He'd been chosen by Sukarno over his eventual successor, Subekti, against the recommendations of the Parliament of Indonesia during the era of guided democracy.[9] Part of Sukarno's reasoning was that Subekti played "poker",[10] leading to the impression among the judiciary that Suryadi had been chosen due to his relationship with Sukarno in the Indonesian National Party.[9]

The friction ultimately led to his resignation. The Judges' Association planned to hold a meeting to discuss numerous issues, including Suryadi's attempt to order unfavorable transfers to a number of district judges and the Justice Minister's rejection of it, in November 1966.[11] Suryadi threatened to boycott the meeting, but attended for a time when the Association didn't budge. While he was physically present, none dared to air any criticism of him; once he walked out, his colleagues began to berate him.[11] After the fall of Sukarno, the Parliament began to consider Atmaja and Sukito for nomination to the Supreme Court, at which point Suryadi announced that he'd refuse to serve alongside them. The Parliament then followed through with the appointment of both individuals, upon which Suryadi resigned and was promptly replaced by Subekti.[11]

Legacy

The comprehensive demands of the Indonesian judiciary in terms of their role in the state were drawn up by Suryadi at a separate November 1966 conference.[12] Ironically, it was Suryadi rather than the Judges' Association that articulated the judiciary's view of its own role which remains consistent until the present day.[13] A number of his former opponents regretted their conflict with him in light of his coherent expression of what could have been the most major political milestone in Indonesia's post independence history.[13]

Suryadi's predictions about the conflict between judges and prosecutors have also been described as "prophetic."[14] In the 1950s, Indonesian prosecutors argued for equality between their salaries and those of judges; Suryadi argued that reducing the relative prestige of judges would result in difficulty recruiting capable candidates. Even by the early 1950s, more law graduates pursued careers as prosecutors and the Indonesian judiciary faced an acute shortage of trained personnel.[14]

After his retirement, Suryadi was hired at the law firm of rights activist Adnan Buyung Nasution.[13]

References

- 1 2 Daniel Lev, Legal Evolution and Political Authority in Indonesia, pg. 77. Leiden: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 2000. ISBN 9789041114211

- 1 2 Sebastian Pompe, The Indonesian Supreme Court: A Study of Institutional Collapse, pg. 47. Ithaca: Cornell Southeast Asia Program, 2005. ISBN 9780877277385

- 1 2 Daniel Lev, Legal Evolution, pg. 83.

- ↑ "Opperrechter Soerjadi geïnstalleerd" [Chief Justice Soerjadi installed]. De Leidse Courant (in Dutch). ANP. 22 June 1966.

- ↑ Sebastian Pompe, The Indonesian Supreme Court, pgs. 47-48.

- ↑ Sebastian Pompe, The Indonesian Supreme Court, pg. 48.

- ↑ Sebastian Pompe, The Indonesian Supreme Court, pg. 69.

- 1 2 Sebastian Pompe, The Indonesian Supreme Court, pg. 84.

- 1 2 Sebastian Pompe, The Indonesian Supreme Court, pg. 83.

- ↑ Sebastian Pompe, The Indonesian Supreme Court, pg. 82.

- 1 2 3 Sebastian Pompe, The Indonesian Supreme Court, pg. 86.

- ↑ Sebastian Pompe, The Indonesian Supreme Court, pg. 87.

- 1 2 3 Sebastian Pompe, The Indonesian Supreme Court, pg. 88.

- 1 2 Daniel Lev, Legal Evolution, pg. 82.