According to PIMS (profit impact of marketing strategy), an important lever of business success is growth. Among 37 variables, growth is mentioned as one of the most important variables for success: market share, market growth, marketing expense to sales ratio[1] or a strong market position.[2]

The question how much growth is sustainable is answered by two concepts with different perspectives:

- The sustainable growth rate (SGR) concept by Robert C. Higgins, describes optimal growth from a financial perspective assuming a given strategy with clear defined financial frame conditions/ limitations. Sustainable growth is defined as the annual percentage of increase in sales that is consistent with a defined financial policy (target debt to equity ratio, target dividend payout ratio, target profit margin, target ratio of total assets to net sales). This concept provides a comprehensive financial framework and formula for case/ company specific SGR calculations.[3]

- The optimal growth concept by Martin Handschuh, Hannes Lösch, Björn Heyden et al. assesses sustainable growth from a total shareholder return creation and profitability perspective—independent of a given strategy, business model and/ or financial frame condition. This concept is based on statistical long-term assessments and is enriched by case examples. It provides an orientation frame for case/ company specific mid- to long-term growth target setting.[4]

From a financial perspective

The sustainable growth rate is the growth rate in profits that a company can reasonably achieve, consistent with its established financial policy. Relatedly, an assumption re the company's sustainable growth rate is a required input to several valuation models — for instance the Gordon model and other discounted cash flow models — where this is used in the calculation of continuing or terminal value; see Valuation using discounted cash flows.

Several formulae are available here.[5] In general, these link long term profitability targets, dividend policy, and capital structure assumptions, returning the sustainable, long-run business growth-rate attainable as a function of these. These formulae reflect the general requirement that all assumptions are internally consistent; see Financial modeling § Accounting. The sustainable growth rate may be returned via the following formula: [6]

-

- pm is the existing and target profit margin

- d is the target dividend payout ratio

- L is the target total debt to equity ratio

- T is the ratio of total assets to sales

Note that the model presented here, assumes several simplifications: the profit margin remains stable; the proportion of assets and sales remains stable; related, the value of existing assets is maintained after depreciation; the company maintains its current capital structure and dividend payout policy.

A check on the formula inputs, and on the resultant growth number, is provided by a respective twofold economic argument.

- The macroeconomic check: The long-run growth of the company (industry) cannot exceed overall economic growth by any significant amount — otherwise the company in question would eventually constitute the bulk of the economy; see Earnings growth § Relationship with GDP growth. A calculated growth rate, where the given assumptions are input to a growth formula, can then also act a check as to whether budgets or business plans are reasonable.

- The microeconomic argument: Where the (risk adjusted) Return on capital is significantly higher than achievable in other industries, then this success will attract competition; in the long-run then, the company's returns will tend to those of its industry, in turn tending to the economy; see Profit (economics). Formulae inputs — i.e. assumed profit as compared to targeted capital structure — must be limited correspondingly.

Optimal growth rates from a total shareholder value creation and profitability perspective

Optimal growth according to Martin Handschuh, Hannes Lösch and Björn Heyden is the growth rate which assures sustainable company development – considering the long-term relationship between revenue growth, total shareholder value creation and profitability. Assessment basis: The work is based on assessments on the performance of more than 3500 stock-listed companies with an initial revenue of greater 250 million Euro globally and across industries over a period of 12 years from 1997 till 2009. Due to this long time period, the authors consider their findings as to a large extent independent of specific economic cycles.[4]

Relationship between revenue growth, total shareholder value creation and profitability

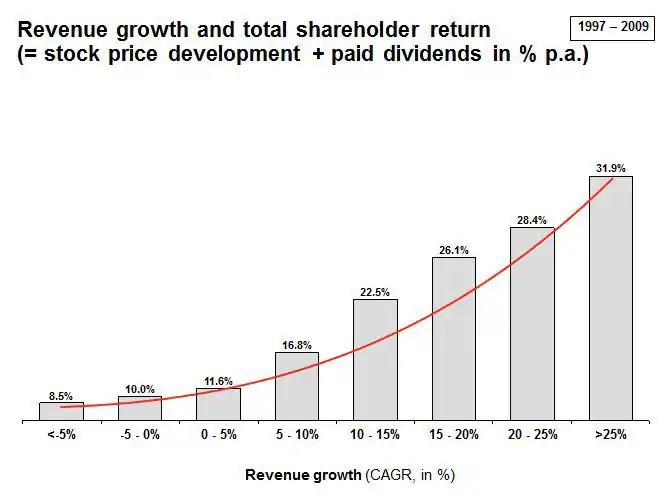

In the long-term and across industries, total shareholder value creation (stock price development plus dividend payments) rises steadily with increasing revenue growth rates. The more long-term revenue growth companies realize, the more investors appreciate this and the more they get rewarded.

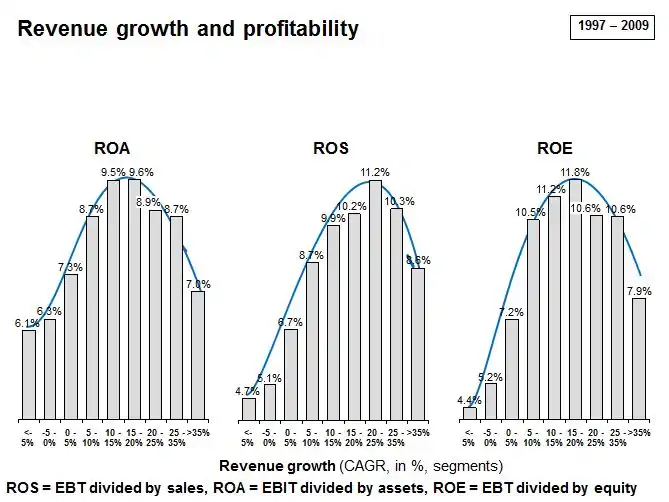

Return on assets (ROA), return on sales (ROS) and return on equity (ROE) do rise with increasing revenue growth up to 10 to 25% and then fall with further increasing revenue growth rates.

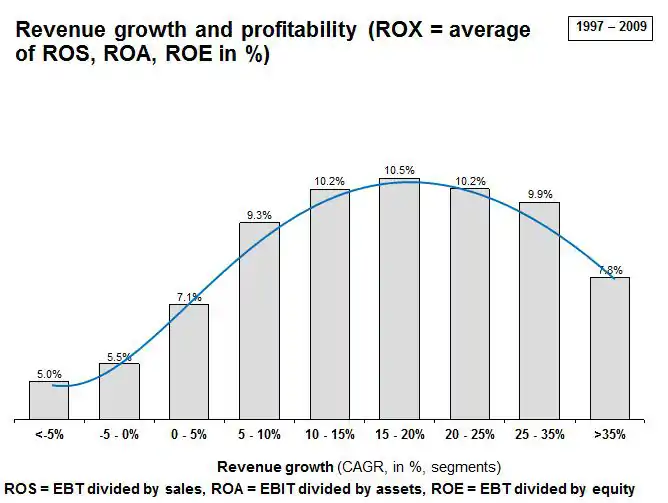

Also the combined ROX-index (average of ROA, ROS and ROE) shows rises with increasing growth rates to a broad maximum in the range of 10 to 25% revenue growth per year and falls towards higher growth rates.

The authors attribute the continuous profitability increase towards the maximum of two effects:

- Profitability drives growth: Companies with substantial profitability have the opportunity to invest more in additional growth.

- Growth drives profitability: Substantial growth may be a driver for additional profitability, e.g. by higher attractiveness for high performing young professionals, higher employee motivation, higher attractiveness for business partners as well as higher self-confidence.

Beyond the profitability maximum extra efforts to handle additional growth – e.g. based on integrating new staff in large dimensions and handling culture and quality - do rise sharply and reduce overall profitability.

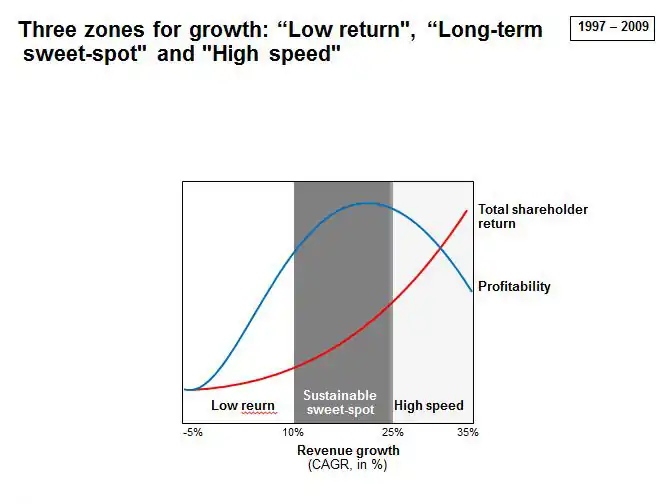

The combination of the patterns of revenue growth, total shareholder value creation and profitability indicates three growth zones:

- Low Return: Low profitability and low value generation below 10% per year

- Long-term Sweet-Spot: Solid value generation and highest on average profitability in the revenue growth interval from 10% to 25% per year

- High Speed: Even higher total shareholder value generation however in combination with lower profitability beyond 25% per year

Growth rates of the assessed companies are widely independent of initial company size/market share which is in alignment with Gibrat's law. Gibrat's law, sometimes called Gibrat's rule of proportionate growth is a rule defined by Robert Gibrat (1904–1980) stating that the size of a firm and its growth rate are independent. Independent of industry consolidation and industry growth rate, companies in many industries with growth rates in the range of 10 to 25% revenue growth p.a. have both, higher total shareholder value generation as well as profitability than their slower growing peers.

Base strategies and growth moves

These findings do suggest two base strategies for companies:

- For companies (e.g. in established markets like central Europe and USA) with low single-digit growth rates: Consider acceleration of growth given the fact that corporate social responsibility (CSR) and profitability are higher in the sweet-spot.

- For companies (e.g. in fast growing regional markets like China with India and/ or rapidly growing industry segments) with growth rates beyond 25%: Consider best ways to “digest” and to stabilize rapid growth and ensure a “soft landing” should market growth come to a sudden stop.

How to achieve long-term growth in the sweet-spot and beyond

The authors have identified a set of preconditions and levers to achieve long-term growth in their defined sweet-spot and beyond:

Preconditions

- Generating a common understanding regarding growth and profit ambitions among the management team as a prerequisite for aligned and coordinated strategy development and implementation.

- Understanding relevant markets (current or future promising markets). Generating market foresight when identifying and assessing growth initiatives, e.g. megatrends and scenario analyses, segment specific benchmarking and in depth assessments, market demand projections.

Levers and strategy

- Applying formulas for rapid growth, e.g. maxing out the number of relevant customers, maxing out the share of wallet and lifecycle potentials, continuous innovation, killer offerings, network based growth, M&A/buy-and-build driven growth, franchising proven business concepts, pyramid-like network expansion and managing value networks

- Defining the growth strategy as a portfolio of best suited growth initiatives considering a multidimensional set of criteria, e.g. ease of implementation, growth and profit impact, expected risk vs. return, cash flow stability

- Making growth happen: Strategy and corresponding culture must be addressed in a consistent way, e.g. creating the case for growth, clearly defining and communicating vision and strategy as well as actively developing and energizing the organization.[4]

A study be Davidsson et al. (2009) found that small and medium-sized firms (SMEs) are much more likely to get a position of high growth AND high profitability starting from high profitability/low growth than from high growth/low profitability. Firms with the latter performance configuration instead more often transitioned to low growth/low profitability.

Brännback et al. (2009) replicated these findings in a sample of biotech firms.

Ben-Hafaïedh & Hamelin (2022) undertook a replication on more than 650,000 firms and confirmed the same main result separately in each of 28 studied countries as well as across industry sectors, firm age and size classes, time spans from 1 to 7 years, alternative growth and profitability measures, and using several alternative analysis techniques. The conclusion is that firms do usually not grow into profitability. Instead, profitable growth usually starts with a sound level of profitability at smaller scale. These are arguably among the most consistently data-supported conclusions in all of business research.

Criticism

As described the sustainable growth rate (SGR) concept by Robert C. Higgins is based on several assumptions such as constant profit margin, constant debt to equity ratio or constant asset to sales ratio. Therefore, general applicability of SGR concept in cases where these parameters are not stable is limited.

The Optimal Growth concept by Martin Handschuh, Hannes Lösch, Björn Heyden et al. has no restrictions to certain strategies or business model and is therefore more flexible in its applicability. However, as a broad framework, it only provides an orientation for case/company specific mid- to long-term growth target setting. Additional company and market specific considerations, e.g. market growth, growth culture, appetite for change, are required to come up with the optimal growth rate of a specific company.

Additionally, considering the increasing criticism of excessive growth and shareholder value orientation by philosophers, economists and also managers, e.g. Stéphane Hessel, Kenneth Boulding, Jack Welch (nowadays), one might expect that investors' investment criteria might also change in the future. This may lead to changes in the relationship of revenue growth rates and total shareholder value creation. Regular reviews of the optimal growth assessments may be used as an indicator for the development of stock markets` appetite for rapid growth.

References

- ↑ Lancaster, Geoff; Massingham, Lester; Ashford, Ruth (2001): Essentials of Marketing: Text and Cases, Mcgraw-Hill Higher Education, p. 535

- ↑ Dibb, Sally; Simkin, Lyndon; Pride, William (2005): Marketing.Concepts and Strategies, 5th edition, Houghton Mifflin, p. 676

- ↑ Higgins, Robert (1977): How much growth can a firm afford, Financial Management 6 (3) p. 7-16

- 1 2 3 Börnsen, Arne; Körner, Florian (2011): Optimal Growth, Conceptualization of a strategy to benefit from Optimal Growth, Mannheim Business School

- ↑ See for example, Valuing Companies by Cash Flow Discounting: Ten Methods and Nine Theories, Pablo Fernandez: University of Navarra - IESE Business School

- ↑ Chapter 4 in Robert C. Higgins (2018). Analysis for Financial Management (12th ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-1259918964.

Ben-Hafaïedh, C., & Hamelin, A. (2022). Questioning the Growth Dogma: A Replication Study. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 10422587211059991.

Brännback, M., Carsrud, A., Renko, M., Östermark, R., Aaltonen, J., & Kiviluoto, N. (2009). Growth and profitability in small privately held biotech firms: Preliminary findings. New Biotechnology, 25(5), 369-376.

Davidsson, P., Steffens, P., & Fitzsimmons, J. (2009). Growing profitable or growing from profits: Putting the horse in front of the cart? Journal of Business Venturing, 24(4), 388-406.

Further reading

- Fonseka, Mohan; Tian, Gaoloang (2011): The most appropriate Sustainable Growth Rate (SGR) Model for Managers and Researchers, American Accounting Association

- Graeme, Deans; Kroeger, Fritz (2004): Stretch!: How Great Companies Grow in Good Times and Bad, John Wiley & Sons

- Handschuh, Martin (2011): What we can learn from self-made billionaires?, WHU Otto Beisheim School of Management lecture

- Handschuh, Martin; Lösch, Hannes (2011): Optimal Growth – Does it exist and if so how to realize it?, Mannheim Business School lecture

- Handschuh, Martin; Reinartz, Sebastian; Heyden, Björn (2011): Megafusionen als Lehrbuch, M&A Review 05/2011

- Higgins, Robert (1981): Sustainable growth under inflation, Financial Management 10 (4) p. 36-40

- Jonk, Gillis (2006): Resources for Growth, published in: executive agenda, ideas and insights for business leaders, volume IX, Number 1, 2006, A.T. Kearney

- Lösch, Hannes (2017): The high-growth company: Perils of excessive growth, Master thesis University of Innsbruck

- Lösch, Hannes (2018): Optimal Growth: Optimales Wachstum erhöht Ihren Unternehmenserfolg und steigert Ihren Wert.

- Neumann, Dietrich; Sonnenschein, Martin; Schumacher, Nikolas (2003): Fünf Wege zu organischem Wachstum: Wie Unternehmen antizyklischen Erfolg programmieren können, campus Verlag

- Slywotzky, Adrian; Wise, Richard; Weber, Karl (2004): How to Grow When Markets Don’t: Discovering the New Drivers for Growth

- Sonnenschein, Martin (2011): Innovation and Growth in Volatile Times, Stuttgarter Strategieforum

- Velthius, Carol (2010): Surfing the Long Summer: How Market Leaders Grow Faster Than Their Markets, Infinite Ideas

- Zook, Chris (2007): Unstoppable: Finding Hidden Assets to Renew the Core and Fuel Profitable Growth; Mcgraw-Hill Professional

- Zook, Chris; Allen, James (2010): Profit from the Core: A Return to Growth in Turbulent Times; Harvard Business Press