.svg.png.webp) |

|---|

Elections in Sweden are held once every four years. At the highest level, all 349 members of Riksdag, the national parliament of Sweden, are elected in general elections. Elections to the 20 county councils (Swedish: landsting) and 290 municipal assemblies (kommunfullmäktige) – all using almost the same electoral system – are held concurrently with the legislative elections on the second Sunday in September (with effect from 2014; until 2010 they had been held on the third Sunday in September).

Sweden also holds elections to the European Parliament, which unlike Swedish domestic elections are held in June every five years, although they are also held on a Sunday and use an almost identical electoral system. The last Swedish general election was held on 11 September 2022. The last Swedish election to the European Parliament was held on 26 May 2019.

Electoral system

Dates

Elections to Sweden's county councils occur simultaneously with the general elections on the second Sunday of September. Elections to the municipal councils also occur on the second Sunday of September. Elections to the European Parliament occur every five years in May or June throughout the entire European Union; the exact day of the election varies by country according to the local tradition, thus in Sweden they happen on a Sunday.

Voter eligibility

To vote in a Swedish general election, one must be:[1]

- a Swedish citizen,

- at least 18 years of age on election day,

- and have at some point been a registered resident of Sweden (thus excluding foreign-born Swedes who have never lived in Sweden)

To vote in Swedish local elections (for the county councils and municipal assemblies), one must:[1]

- be a registered resident of the county or municipality in question and be at least 18 years of age on election day

- fall into one of the following groups:

- Swedish citizens

- Citizens of Iceland, Norway, or any country in the European Union

- Citizens of any other country who have permanent residency in Sweden and have lived in Sweden for three consecutive years

In order to vote in elections to the European Parliament, one must be 18 years old, and fall into one of the following groups:[1]

- Swedish citizens who are or have been residents of Sweden

- Citizens of any other country in the European Union who are currently residents of Sweden; such citizens, by choosing to vote in European Parliamentary elections in Sweden, become ineligible to vote in European Parliamentary elections in any other EU member state

In general, any person who is eligible to vote is also eligible to stand for election.

Sweden does not disenfranchise prisoners or those with criminal convictions.[2] Expat Swedish citizens may however be removed from the polling register if they do not renew their registration every 10 years.

Voting

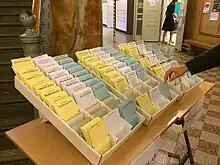

Unlike in many countries where voters chose from a list of candidates or parties, each party in Sweden has separate ballot papers. The ballot papers must be identical in size and material, and have different colors depending on the type of election: yellow for Riksdag elections, blue for county council elections and white for municipal elections and elections to the European Parliament.

Sweden uses open lists and utilizes apparentment between lists of the same party and constituency to form a cartel, a group of lists that are legally allied for purposes of seat allocation.[3] A single preference vote may be indicated as well.[4]

Swedish voters can choose between three different types of ballot papers. The party ballot paper has simply the name of a political party printed on the front and is blank on the back. This ballot is used when a voter wishes to vote for a particular party, but does not wish to give preference to a particular candidate. The name ballot paper has a party name followed by a list of candidates (which can continue on the other side). A voter using this ballot can choose (but is not required) to cast a personal vote by entering a mark next to a particular candidate, in addition to voting for their political party. Alternatively, a voter can take a blank ballot paper and write a party name on it.[5] Finally, if a party has not registered its candidates with the election authority, it is possible for a voter to manually write the name of an arbitrary candidate. In reality, this option is almost exclusively available when voting for unestablished parties. However, it has occasionally caused individuals to be elected into the city council to represent parties they do not even support as a result of a single voter's vote.[6]

The municipalities and the national election authority have the responsibility to organise the elections. On the election day, voting takes place in a municipal building such as a school. It is possible to do early voting, also in a municipal building which is available in day time, such as a library. Early voting can be performed anywhere in Sweden, not just in the home municipality.

Long-standing Swedish election policy of always displaying the ballot papers for voters to select in public, making it impossible for many voters to vote secretly, has been criticised as undemocratic and is arguably in blatant contravention of Protocol 1, Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) which clearly stipulates that elections must be free and by secret ballot. Whilst many wrongly believe that the use of masking by selecting multiple ballot papers is an effective mitigation of this lack of secrecy, it is readily demonstrated that it cannot be considered as such by simply considering a case where an individual is being coerced into not voting for a particular party.

In 2014 a German citizen, Christian Dworeck, reported this lack of secrecy in Swedish voting to the European Commission[7] and from 2019 ballot papers are selected behind a screen.[8] It remains to be seen if this measure, quietly introduced to bring EU elections in Sweden into compliance with European human rights law. This measure has now been implemented in Swedish parliamentary and local elections as was seen in the Swedish General Election of 2022 (a picture can be seen in the linked reference).[9]

Cost of ballot papers

For the general elections, the State pays for the printing and distribution of ballot papers for any party which has received at least one percent of the vote nationally in either of the previous two elections. For local elections, any party that is currently represented in the legislative body in question is entitled to free printing of ballot papers.[10][11]

Constituencies

In Riksdag elections, constituencies are usually coterminous with one of the Swedish counties, though the Counties of Stockholm, Skåne (containing Malmö), and Västra Götaland (containing Gothenburg) are divided into smaller electoral constituencies due to their larger populations. The number of available seats in each constituency is based on its number of voters (vis-à-vis the number of voters nationwide), and parties are apportioned seats in each constituency based on their votes in that constituency.[12]

In County Council elections, individual municipalities—or alternatively groups of municipalities—are used as electoral constituencies. The number of seats on the county council allocated to each constituency, and the borders of these constituencies, is entirely at the discretion of each county council itself. As mandated by Swedish law, nine out of ten seats on each county council are permanent seats from a particular constituency; the remaining seats are at-large adjustment seats, used to ensure county-wide proportionality with the vote, just as with general elections.[5]

For European parliamentary elections, all of Sweden consists of one electoral district.

Party list candidate selection

In Sweden the seats of the Riksdag are allocated to the parties, and the prospective members are selected by their party.[12] Sweden uses open lists and utilizes apparentement between lists of the same constituency and party to form a cartel, a group of lists that are legally allied for purposes of seat allocation.[3] Which candidates from which lists are to secure the seats allocated to the party is determined by two factors: preference votes are first used to choose candidates which pass a certain threshold,[13] then the number of votes cast for the various lists within that party are used.[3][14][13] In national general elections, any candidates who receive a number of personal votes equal to five percent or greater of the party's total number of votes will automatically be bumped to the top of the list, regardless of their ranking on the list by the party. This threshold is similarly five percent for local elections and elections to the European Parliament.[15]

Although sometimes dissatisfied party supporters put forward their own lists, the lists are usually put forward by the parties, and target different constituencies and categories of voters.[14] Competition between lists is usually more of a feature of campaign strategies than for effective candidate preferences, and does not bear prominently in elections.[14]

Because seats are allocated primarily to the parties and not candidates, the seat of an MP who resigns during their term in office can be taken by a replacement runner-up candidate from their own party (unlike systems such as the United Kingdom, a by-election is not triggered). In contrast to assigning the seat, resigning is a voluntary action of the MP, meaning that there exists the possibility of MPs resigning from their parties but not their seats and sitting as independents. The system of replacement runner-up candidates also means that the Prime Minister and their potential members of cabinet appear on ballot papers, but surrender their seats to replacement candidates as they are appointed as ministers (holding both posts is not permitted). This allows senior party politicians to assume roles as opposition members of parliament if they lose an election.

Seat allocation

Seats in the various legislative bodies are allocated amongst the Swedish political parties proportionally using a modified form of the Sainte-Laguë method. This modification creates a systematic preference in the mathematics behind seat distribution, favoring larger and medium-sized parties over smaller parties. It reduces the slight bias towards larger parties in the d'Hondt formula. At the core of it, the system remains intensely proportional, and thus a party which wins approximately 25% of the vote should win approximately 25% of the seats. An example of the close correlation between seats and votes can be seen below in the results of the 2002 Stockholm municipal election.

In Riksdag elections, 310 of the members are elected using a party-list proportional representation system within each of Sweden's 29 electoral constituencies. The remaining 39 seats in the Riksdag are "adjustment seats", distributed amongst the parties in numbers that will ensure that the party distribution in the Riksdag matches the distribution of the votes nationally as closely as possible.[12] County elections use the same system. All seats on municipal assemblies are permanent; there are no adjustment seats. This can cause the distribution of seats in the municipal assemblies to differ somewhat from the actual distribution of votes in the election.[16] The European Parliament has 751 permanent seats, 20 of which were allocated to Sweden for the 2019 election. After Brexit, an additional seat was allocated for Sweden.[17]

In order to restrict the number of parties which win seats in the Riksdag, a threshold has been put in place. In order to win seats in the Riksdag, a party must win at least four percent of the vote nationally, or twelve percent of the vote in any electoral constituency.[16] County elections use a lower threshold of three percent. For municipal elections, since the elections of 2018 there has been a minimum threshold of two percent in municipalities with only one constituency, and three percent in those with more than one.[18]

Comparison of vote share vs. share of allocated seats after 2018 municipal elections:[19]

| Party | Votes (%) | Seats (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social Democratic Party | 27.6 | 29.5 | |

| Moderate Party | 20.1 | 18.9 | |

| Sweden Democrats | 12.7 | 14.2 | |

| Centre Party | 9.7 | 12.6 | |

| Left Party | 7.7 | 6.4 | |

| Liberals | 6.8 | 5.4 | |

| Christian Democrats | 5.2 | 5.3 | |

| Green Party | 4.6 | 3.1 | |

Terms of office

The assembly members are elected for a fixed term of four years. In 1970 to 1994, terms were three years; before that, normally four. The Riksdag may be dissolved earlier by a decree of the prime minister, in which case new elections are held; however, new members will hold office only until the next ordinary election, the date of which remains the same. Thus the terms of office of the new members will be the remaining parts of the terms of the MPs in the dissolved parliament.

The unicameral Riksdag has never been dissolved by decree. The last time the second chamber of the old Riksdag was dissolved in this manner was in 1958.

The regional and local assemblies cannot be dissolved before the end of their term.

Party organization

While parties have been very careful to maintain their original mass party image, party organizations have become increasing professionalized and dependent on the state, and less connected with their grass-roots members and civil society.[20][21] Party membership has declined to 210,067 members in 2010 across all parties (3.67% of the electorate), from 1,124,917 members in 1960 (22.62% of the electorate).[20] Political parties can be registered with the support of 1500 electors for Riksdag elections, 1500 electors for EU elections, 100 electors for county council elections, and/or 50 electors for municipal elections.[22]

Riksdag elections

The unicameral Parliament of Sweden has 349 members: 310 are elected using party-list proportional representation, and 39 using "adjustment seats".

Latest result

At the 2018 general elections the red-green coalition consisting of Social Democrats, Greens and the Left got 40.7% of the votes compared to 40.3% for the Alliance parties, resulting in a single-seat difference between the blocks. After a prolonged government formation process, Stefan Löfven was able to form a minority government with the Greens, conditional on external support from Centre Party and the Liberals.

Riksdag election results in percent of the vote 1911–2022

The first elections to a unicameral Riksdag were held in 1970. The older figures refer to elections of the Andra kammaren under the older bicameral system.[23][24]

Note that, as of 12 September 2022, the 2022 results are still preliminary; official results will be announced about two weeks after the election.[25]

| Year | V | S | MP | L | C | M | KD | SD | Various | Others | Turnout |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2022 | 6.8 | 30.3 | 5.1 | 4.6 | 6.7 | 19.1 | 5.3 | 20.5 | 1.5 | 84.2% | |

| 2018 | 8.0 | 28.3 | 4.4 | 5.5 | 8.6 | 19.8 | 6.3 | 17.5 | 1.6 | 87.2% | |

| 2014 | 5.7 | 31.0 | 6.9 | 5.4 | 6.1 | 23.3 | 4.6 | 12.9 | 3.1 (Fi) | 1.4 | 85.8% |

| 2010 | 5.6 | 30.7 | 7.3 | 7.1 | 6.6 | 30.1 | 5.6 | 5.7 | 1.4 | 84.6% | |

| 2006 | 5.9 | 35.0 | 5.2 | 7.5 | 7.9 | 26.2 | 6.6 | 2.9 | 2.7 | 82.0% | |

| 2002 | 8.4 | 39.9 | 4.7 | 13.4 | 6.2 | 15.3 | 9.1 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 80.1% | |

| 1998 | 12.0 | 36.4 | 4.5 | 4.7 | 5.1 | 22.9 | 11.8 | 0.4 | 2.2 | 81.4% | |

| 1994 | 6.2 | 45.3 | 5.0 | 7.2 | 7.7 | 22.4 | 4.1 | 1.2 (NyD) | 1.0 | 86.4% | |

| 1991 | 4.5 | 37.6 | 3.4 | 9.1 | 8.5 | 21.9 | 7.1 | 6.7 (NyD) | 1.2 | 86.7% | |

| 1988 | 5.8 | 43.2 | 5.5 | 12.2 | 11.3 | 18.3 | 2.9 | 0.7 | 86.0% | ||

| 1985 | 5.4 | 44.7 | 1.5 | 14.2 | 10.1 | 21.3 | 2.3 | 0.5 | 89.9% | ||

| 1982 | 5.6 | 45.6 | 1.7 | 5.9 | 15.5 | 23.6 | 1.9 | 0.2 | 91.4% | ||

| 1979 | 5.6 | 43.2 | 10.6 | 18.1 | 20.3 | 1.4 | 0.8 | 90.7% | |||

| 1976 | 4.8 | 42.7 | 11.1 | 24.1 | 15.6 | 1.4 | 0.4 | 91.8% | |||

| 1973 | 5.3 | 43.6 | 9.4 | 25.1 | 14.3 | 1.8 | 0.6 | 90.8% | |||

| 1970 | 4.8 | 45.3 | 16.2 | 19.9 | 11.5 | 1.8 | 0.4 | 88.3% | |||

| Andra kammaren | |||||||||||

| 1968 | 3.0 | 50.1 | 14.3 | 15.7 | 12.9 | 1.5 | 2.6 | 89.3% | |||

| 1964 | 5.2 | 47.3 | 17.0 | 13.2 | 13.7 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 83.3% | |||

| 1960 | 4.5 | 47.8 | 17.5 | 13.6 | 16.5 | 0.1 | 85.9% | ||||

| 1958 | 3.4 | 46.2 | 18.2 | 12.7 | 19.5 | 0.0 | 77.4% | ||||

| 1956 | 5.0 | 44.6 | 23.8 | 9.4 | 17.1 | 0.1 | 79.8% | ||||

| 1952 | 4.3 | 46.1 | 24.4 | 10.7 | 14.4 | 0.1 | 79.1% | ||||

| 1948 | 6.3 | 46.1 | 22.8 | 12.4 | 12.3 | (SP) | 0.1 | 82.7% | |||

| 1944 | 10.3 | 46.7 | 12.9 | 13.6 | 15.9 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 71.9% | |||

| 1940 | 3.5 | 53.8 | 12.0 | 12.0 | 18.0 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 70.3% | |||

| 1936 | 3.3 | 45.9 | 12.9 | 14.3 | 17.6 | 4.4 | 1.6 | 74.5% | |||

| 1932 | 3.0 | 41.7 | 11.7 | 14.1 | 23.5 | 5.3 | 0.7 | 68.6% | |||

| 1928 | 6.4 | 37.0 | 15.9 | 11.2 | 29.4 | 0.1 | 67.4% | ||||

| 1924 | 5.1 | 41.1 | 16.9 | 10.8 | 26.1 | (SSV) | 0.0 | 53.0% | |||

| 1921 | 4.6 | 36.2 | 19.1 | 11.1 | 25.8 | 3.2 | 0.0 | 54.2% | |||

| 1920 | 6.4 | 29.7 | 21.8 | 14.2 | 27.9 | 0.0 | 55.3% | ||||

| 1917 | 8.1 | 31.1 | 27.6 | 8.5 | 24.7 | 0.0 | 65.8% | ||||

| 1914 (Sept.) | 36.4 | 26.9 | 0.2 | 36.5 | 0.0 | 66.2% | |||||

| 1914 (Mar.) | 30.1 | 32.2 | 37.7 | 0.0 | 69.9% | ||||||

| 1911 | 28.5 | 40.2 | 31.2 | 0.1 | 57.0% | ||||||

County Council elections

County Council elections results

Municipal elections

Municipal elections results

Stockholm Municipality

Other municipalities

Elections to the European Parliament

| Members of the European Parliament for Sweden | |

|---|---|

| Delegation | (1995) |

| 4th term | (1995) |

| 5th term | (1999) |

| 6th term | (2004) |

| 7th term | (2009) |

| 8th term | (2014) |

| 9th term | (2019) |

The most recent European parliamentary elections in Sweden were held in May 2019.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 How to vote

- ↑ "Prisoner votes by European country". BBC News. 22 November 2019. Archived from the original on 21 June 2019.

- 1 2 3 Cox 1997, p. 61.

- ↑ Elections, p. 12.

- 1 2 Elections, p. 7.

- ↑ "Jimmy Åkesson kan tvingas representera SD". 25 October 2012.

- ↑ Radio, Sveriges. "EU-kommissionen kräver svar om Sveriges val är hemliga nog" [EU Commission questions Sweden on the insufficient secrecy of its voting system]. sverigesradio.se (in Swedish). Retrieved 8 February 2020.

- ↑ Radio, Sveriges. "Skärmar införs i EU valet – EU-valet 2019" [Screens introduced in the EU election]. sverigesradio.se (in Swedish). Retrieved 5 June 2019.

- ↑ Walsh, Michael (1 August 2022). "Concern potential election day queues may affect voter turnout". Sveriges Radio. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- ↑ Elections, p. 8.

- ↑ Choe, Yonhyok. 1997. How to Manage Free and Fair Elections. Göteborg: Göteborg University.

- 1 2 3 Ewing 2010, p. 151.

- 1 2 Elections, p. 20.

- 1 2 3 Särlvik 1983, p. 134.

- ↑ Elections, p. 16.

- 1 2 Elections, p. 13.

- ↑ "European Parliamentary election results". Valmyndigheten. 31 May 2019.

- ↑ Statistics, p. 14.

- ↑ "Val till kommunfullmäktige – Valda 2018" (in Swedish). Valmyndigheten. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- 1 2 Elingsson, Gissur; Kölln, Ann-Kristen; Öhberg, Patrik (2016). "The Party Organizations". In Pierre, Jon (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Swedish Politics. Oxford University Press. pp. 169–187. ISBN 9780199665679. LCCN 2015958065.

- ↑ Pierre, Jon; Widfeldt, Anders (1994). "Party Organizations in Sweden: Colossus with Feet of Clay or Flexible Pillars of Government?". In Katz, Richard; Mair, Peter (eds.). How Parties Organize: Change and Adaptation in Party Organizations in Western Democracies. SAGE Publications. pp. 332–356. ISBN 0803979614. LCCN 94068658.

- ↑ Electoral law, SFS 2005:837 ch. 2 § 3

- ↑ "Historisk statistik över valåren 1910–2014. Procentuell fördelning av giltiga valsedlar efter parti och typ av val" (in Swedish). Statistics Sweden. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ↑ "Election results 2018". Valmyndigheten. 17 September 2018.

- ↑ "Slutligt valresultat". Valmyndigheten (in Swedish). 1 July 2022. Retrieved 12 September 2022.

- Swedish Election Authority. "Elections in Sweden The way it´s done!" (PDF).

- Ewing, Keith D. (2010). The Funding of Political Parties in Britain. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-12406-5.

- Cox, Gary W. (1997). Making Votes Count: Strategic Coordination in the World's Electoral Systems. Political Economy of Institutions and Decisions. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-58527-9.

- Särlvik, Bo (1983). "Scandinavia". In Bogdanor, Vernon; Butler, David (eds.). Democracy and Elections: Electoral Systems and Their Political Consequences. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-27282-3.

- Statistics Sweden. "Highest turnout since 1985 general elections".

External links

- Swedish Election Authority – Official site (in English)

- Valmyndigheten – Official site (in Swedish)

- Statistics Sweden: Elections 1910-2005 – Official site (in Swedish)

- United States Department of State – Sweden (in English)

- Adam Carr's Election Archive (in English)

- Parties and Elections in Europe (in English)

- European Democracies – Electoral Reform Society briefing (.pdf format) (in English)

- NSD: European Election Database – Sweden publishes regional level election data; allows for comparisons of election results, 1991–2006