Swing, in the politics of the United Kingdom, is a number used as an indication of the scale of voter change between two political parties. It originated as a mathematical calculation for comparing the results of two Parliamentary constituencies. The UK uses a first-past-the-post voting system. The swing (in percentage points) is the percentage of voter support minus the comparative percentage of voter support corresponding to the same electorate or demographic.

The swing is calculated by comparing the percentage of voter support from one election to another. The percentage value of the comparative elections results are compared with the corresponding results of the substantive election. An electoral swing analysis shows the extent of change in voter support from one election to another. It can be used as a means of comparison between individual candidates or political parties for a given electoral region or demographic.

Original mathematical calculation

The original mathematical construct Butler swing is defined as the average of the Conservative Party percentage-point gain and Labour Party percentage-point loss between two elections, calculated on the basis of the total number of votes (including those cast for candidates other than Conservative or Labour). There is an alternative version called Steed swing which calculates the swing on the basis of votes cast for Conservative and Labour only. It is possible for the same election to have a Butler swing of one sign and a Steed swing of the other.

As an example, assume that a constituency had two sequential election results as follows:

| Party | Previous election (%) | Current election (%) | ± |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conservatives | 35 | 45 | +10 |

| Labour | 45 | 40 | −5 |

| Liberal Democrats | 20 | 15 | −5 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | – |

The Butler swing to the Conservatives is therefore:

The Steed swing is slightly more complicated to calculate, as it focuses on the shift between two specific parties (ignoring all others). In the above case, the swing to the Conservatives would be:

Labour would have a corresponding loss in the same amount:

Creation

Swing was originated by David Butler, a political science academic at Nuffield College, Oxford. In a contribution to The British General Election of 1945 he wrote "this measurement of 'swing', admittedly imperfect, does give us a broad idea of the movement of opinion from Conservative to Labour" and went on to compare the swings in each area of the country.

The concept became important in the general elections of the 1950s when it was found that there was a relatively uniform swing across all constituencies. This made it easy to predict the final outcomes of general elections when few actual results were known, as the swing in the first constituencies to declare could be applied to every seat.

Only a relatively small proportion of seats in most UK general elections are marginal seats, and thus likely to change party. The swing enabled prediction of outcomes to be made even while safe seats were returning results whose victors were not in doubt. In several elections, such as 1970, the swing correctly predicted a majority for the then opposition even while government party victories seemed to predominate.

Taking the national vote shares in an opinion poll could also easily be translated into likely seat outcomes. Election-night television programmes from 1955 have usually featured a device known as the "swingometer" which consisted of a pendulum which could point to the swing nationally and illustrate the outcome.

Problems and development

During the postwar period British politics was characterised by a strong two-party system. Almost all voters who changed their preference from one election to another, swung between the two main parties. There has been a much greater variety in change since the re-emergence of three-party politics in the 1970s. The original calculation of swing did not make any allowance for other parties and when the votes for other parties rose, demands arose for a more sophisticated measurement. The continuation of the first-past-the-post system, and the tendency for smaller parties to only run in some constituencies, made it increasingly difficult to use measures of swing to predict results.

The Liberals (and, later, Liberal Democrats) have been the main catalyst for this change, providing a credible nationwide alternative to the two main parties. The success of the SNP in Scotland and Plaid Cymru in Wales, especially in elections to the Scottish Parliament and Welsh Assembly, has also had an effect. Two other mass parties – the Green Party, which emerged in the 1980s, and UKIP, which emerged in the 1990s – won no seats in Parliament until the Greens took Brighton Pavilion in the 2010 general election, but have had a significant effect on the swing in certain areas, most notably the Greens in Brighton Pavilion.

Swing has also been complicated since the 1970s as the constituent areas of the UK have become increasingly fractured. This has led to swings being very different in different areas – for instance, 1992 saw a swing to the Scottish Conservatives in Scotland, but a swing to Labour in South East England.

At the same time, other parties began to win significant levels of representation in the House of Commons. This has led to swing becoming a measurement of the changes in votes of the two biggest parties in the constituency in question, rather than just Labour and the Conservatives.

Simply substituting the Liberal Party for the Labour Party in the calculation provides a measure of a 'swing between Conservative and Liberal'. However election results showed that this was not a useful predictor in seats which were being fought by these parties. It came to be used as a measure of the significance of the change of the vote. Almost all published election results are derived from the Press Association results service which in recent years shows the swing as between the two parties that came first and second, rather than strictly between Conservative and Labour. For this reason, the direction of swing is explicitly stated, rather than simply indicated through the sign as applies to Butler Swing.

Analysis of relative party strengths

As swing analysis can be applied to the results of any two parties relative to each other, it is possible to assess parties' relative strengths, as seen in analysis of the 2010 United Kingdom general election:

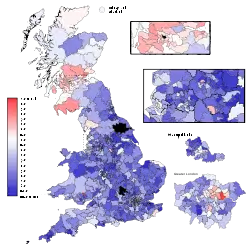

Labour to Conservative swing

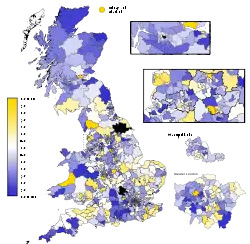

Labour to Conservative swing Liberal Democrat to Conservative swing

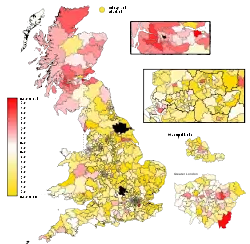

Liberal Democrat to Conservative swing Labour to Liberal Democrat swing

Labour to Liberal Democrat swing

Measurements

Butler swings of more than 10 points are very rare. Taking UK politics after 1945 exclusively (as that election occurred ten years after its predecessor, and in a completely different political climate), only the 1997 general election had a national swing of more than 10 points (−10.23 points). The table below shows the national swing across Great Britain, and the number of individual constituencies out of more than 600 which had a swing of more than 10 points.

| General election | National swing (Lab to Con) | >10-point swings to Labour | >10-point swings to Conservative |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1951 | +1.09 | 1 | – |

| 1955 | +1.74 | – | – |

| 1959 | +1.12 | 3 | – |

| 1964 | −3.01 | 7 | – |

| 1966 | −2.7 | – | – |

| 1970 | +4.81 | – | 4 |

| Feb. 1974 | −0.74 | 6 | 1 |

| Oct. 1974 | −2.12 | – | – |

| 1979 | +5.29 | – | 23 |

| 1983 | +4.07 | – | 9 |

| 1987 | −1.75 | 6 | – |

| 1992 | −2.08 | 1 | 1 |

| 1997 | −10.23 | 364 | – |

| 2001 | +1.80 | – | – |

| 2005 | +3.15 | – | 2 |

| 2010 | +5.17 | – | 36 |

| 2015 | −0.35 | 1 | 7 |

| 2017 | +1.8[1] | – | 12 |

| 2019 | – | ||

Conventional swing is much more volatile, and many more constituencies have large conventional swings. In addition, the conventional swing in a constituency where the top two candidates are not Conservative and Labour cannot be meaningfully compared with the national or regional swing.

See also

References

- ↑ Travis, Alan (9 June 2017). "The youth for today: how the 2017 election changed the political landscape". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- The British General Election of 1945 by R. B. McCallum and Alison Readman (Oxford University Press, 1947) pages 263–65

- Political Change in Britain by David Butler and Donald Stokes (Macmillan, 1969) pages 140–51