| General Post Office Sydney | |

|---|---|

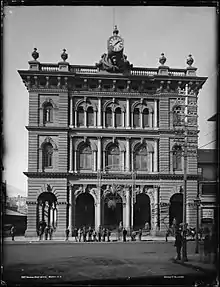

The GPO as viewed from Pitt Street | |

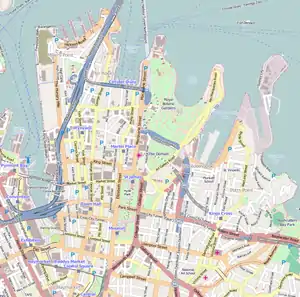

Location in Sydney central business district | |

| Alternative names | Sydney GPO |

| General information | |

| Status | Completed |

| Architectural style | |

| Location | No. 1 Martin Place, Sydney central business district, New South Wales |

| Country | Australia |

| Coordinates | 33°52′04″S 151°12′28″E / 33.867716°S 151.207699°E |

| Current tenants |

|

| Groundbreaking | April 1869 (keystone setting) |

| Construction started | 1866 |

| Completed | 1891 |

| Opened | 1 September 1874 |

| Renovated |

|

| Owner | Far East Organisation and Sino Land |

| Height | |

| Antenna spire | 80 metres (260 ft) |

| Technical details | |

| Material | Sydney sandstone |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | |

| Architecture firm | NSW Colonial Architect |

| Main contractor | John Young (1866) |

| Renovating team | |

| Renovating firm |

|

| Type | Historic |

| Criteria | a4., d2., e1., f1., g1., h1. |

| Designated | 22 June 2009 |

| Reference no. | 105509 |

| Official name | General Post Office |

| Type | Built |

| Criteria | a., c., d., e. |

| Designated | 2 April 1999 |

| Reference no. | 763 |

| Type | Post Office |

| Category | Postal and Telecommunications |

| Builders | John Young |

| References | |

| [1][2][3] | |

The General Post Office (abbreviation GPO, commonly known as the Sydney GPO) is a heritage-listed landmark building located in Martin Place, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. The original building was constructed in two stages beginning in 1866 and was designed under the guidance of Colonial Architect James Barnet. Composed primarily of local Sydney sandstone, mined in Pyrmont, the primary load-bearing northern façade has been described as "the finest example of the Victorian Italian Renaissance Style in NSW" and stretches 114 metres (374 ft) along Martin Place, making it one of the largest sandstone buildings in Sydney.[1][4]

Throughout its twenty five year construction process, the GPO was marred by two major controversies, the first of which related to the selection of bells for the campanile clock and the second, more significantly, to the commission of Italian immigrant sculptor Tommaso Sani's "realistic" depictions of people for the carvings along the Pitt Street arcade.[5] Sculpture was an important consideration for architects in the second half of the 19th century. From the very outset Barnet set in motion an ambitious comprehensive carefully conceived sculpture programme, beginning with George Street which was later continued on Martin Place and the Pitt Street facades, evolving with adjustments of treatment as interpreted by the sculptors involved, but with only on one singular occasion departing markedly in any large measure from the original template of carved keystones and alto relief spandrel infill sculpture. The classical mode begun on George Street was largely followed.Drew, Philip (2021). The Fire in the Stone: The Life and Architectural Sculpture of Thomas Vallance Wran 1832–1891 (PhD thesis). Sydney: UNSW. pp. 287–307. doi:10.26190/unsworks/2276. hdl:1959.4/70848. An exception is the main entrance on Martin Place where the Italian sculptor Giovanni Fontana in Sicilian, working from his studio in Chelsea, was commissioned to complete the figure of Queen Victoria, robed as Queen and Empress with her crown and sceptre, at her feet, two symbolic figures of Britannia and New South Wales in Sicilian marble. Beneath the two stretched figures, the English sculptor, Thomas Vallance Wran, created the royal coat of arms dated 1883 and the line of twenty-four classical in situ heads on the colonnade arches, representing either a continent, country or state, namely: Europe, Asia, Russia, Italy, Germany, United States of America, Canada, India, France, Belgium, Austria, Polynesia, on the Pitt Street side, and on the right, George Street side, Australia, New Zealand, Tasmania, Queensland, Ireland, England, Scotland, Victoria, South Australia, Western Australia, Africa and South America.[6] The new electric telegraph technology connected Australia with the world in a matter of days ending the tyranny of distance which, since colonial times, had burdened commerce and trade relations. The heads symbolize this great triumph over time and distance, the General Post Office itself, a celebratory nineteenth-century version of High-tech dressed in a Renaissance garment. The Wran sculptures continued around into Pitt Street where he carved a second coat of arms complementing the arms in George Street and series of keystone heads of the four seasons as symbols of the Post Office as a self-perpetuating never resting service to the people of NSW.

Mixed with the Wran sculpture were a series of controversial and hugely misunderstood alto relief spandrel sculptures by Tommaso Sani[7] reliefs depicting everyday scenes from Sydney life. In reality the Sani reliefs were late less sophisticated examples of the 1840s Italian realist style known as Verismo whose leading exponent was Vicenzo Vela (1820–1891), but drew the ire and derision of an uniformed elite one of whose members was, Frederick Darley (later, the Chief Justice of NSW) who "denigrated the carvings as caricatures", and such was the controversy surrounding these works that it led to debates on aesthetics and taste within the New South Wales Legislative Assembly between 1883 and 1890 in which Barnet was himself called upon to justify and defend his decision.[8] The Verismo style was a break in the solemn and pompous academism and Sani was a Macchiaioli follower associated with the Garribaldi Risorgimento. Despite severe criticism and controversy, by the time of its final completion in 1891, the building was hailed as a turning point for the Colony of New South Wales, and historians have since noted the building's significance as a force for driving prosperity and for the Federation of Australia.[9] Its architectural expression and in particular its Pitt Street carvings have since been hailed as "the beginning of art in Australia," as well as its urban significance in the shaping of Sydney's urban grid and the Martin Place precinct.[4][8]

The building served as the headquarters of Australia Post from its completion until 1996 when it was privatised and refurbished. The scaled back day-to-day counter postal services are now located on the George Street frontage and the outlet is known as the Sydney GPO Post Shop.[10] The old General Post Office post boxes and Poste restante services are now located in the Australia Post site in the Hunter Connection, on the corner of George Street and Hunter Street. Despite significant internal alterations and additions, the façade has remained virtually unchanged and is listed both on the Commonwealth Heritage List and the New South Wales State Heritage Register, as recognition of its architectural and social significance to the history of Australia.[1][2][3]

Location

The site of the GPO falls within the traditional country of the Cadigal people, a part of the Eora Aboriginal nation within the Sydney region and one of the many hundreds of communities which make up the Aboriginal peoples of Australia.[11] Historically noted for being a harbour-dwelling clan, the Cadigal people inhabited the shorelines stretching from inner South Head to the Eastern Suburbs, and west to Warrane (or War-ran, now known as Sydney Cove) and also along parts of today's City of Sydney to Gomora (now known as Darling Harbour).[12][13] The current site of the General Post Office is also situated over the now entirely enclosed Tank Stream, which was once the primary source of fresh water for the Penal Colony of New South Wales, shortly after the arrival the First Fleet on 26 January 1788, under the direction of Arthur Philip, the First Governor.[1][12]

Today, the General Post Office is located along the western end of Martin Place (No. 1 Martin Place) and spans the entire length of this section of public plaza between George and Pitt Streets. Its geographical location within one of Sydney's key central business district (CBD) public spaces makes it a recognisable public landmark, alongside other significant buildings such as the State Savings Bank Building and the MLC Centre. The central axis of its primary façade is also aligned with the ANZAC Cenotaph, a memorial located at the centre of Martin Place, dedicated to the soldiers who fought in World War I.

Origins

The first Sydney post office (1819–1848)

Prior to the construction of the current GPO building, Sydney's first post office was built along Bent Street in 1819. The current site of the GPO did not become associated with the postal service until 1830, when the Bent Street post office was moved to its site on George Street.[14] It was also at this time that a former police office (designed by Francis Greenway), situated on the current George Street facing site of the GPO was also converted to be part of the postal service in the 1830s.[15] It was documented that this land had been purchased many years earlier by the then-Governor, Lachlan Macquarie for "a hogshead of brandy and either £30 or £50."[14]

This new post office along George Street was designed by several other early colonial architects including Mr Abraham and Mr Mortimer Lewis. Both these people are attributed with the design of the Roman Doric hexastyle portico and for the first time, setting this public building apart from its surrounding commercial shops.[4][14] Writing about the newly modified post office in 1848, Joseph Fowles commented that it was "one of the most important buildings in the colony, not merely as regards to the structure, but as being the centre and focus, the heart, as it may be termed, from which the pulse of the civilisation throbs to the remotest extremity of the land."[15]

Board of Enquiry (1848–1866)

Despite several alterations to the post office on George Street, by 1851, a special Board of Enquiry established by the colonial government had concluded that "the building [is] very ill-adapted for the business required to be carried out in it..."[16] Further alterations were added in an attempt to relieve some pressure on the mail service, but nevertheless, the lack of amenities was a source of complaint by workers and one staff member in 1853 described how "the stench in this room is at times so unbearable as to hinder us materially in the performance of our duties."[5] Continued rapid growth and population rise, particularly in New South Wales had placed significant strain on the postal services and the post office building itself, which had now become a public and government concern due to its gross overcrowding and that the system of handling mail was rapidly descending into the danger of collapsing entirely.[5]

Despite these growing problems, the building remained in use but, by 1863, the situation had worsened such that the Doric building had been entirely abandoned and a larger temporary wooden structure to serve as a temporary post office in Wynyard Square (now Wynyard Park) was erected at a government cost of A£4,000.[14][15] It was at this time that James Barnet, having recently been appointed the first Colonial Architect of New South Wales, was instructed to prepare plans for a new post office on the George Street segment of the present site.[14]

Although his intention had always been to create a much grander civic structure, it has also been documented that Barnet entertained suggestions that the existing Doric portico be retained and a new, larger structure be erected behind it. This idea was unique for its time as it was "almost certainly" the first time in Australian architectural history that contemplation for 'retaining' and 'recycling' an existing historic building had been documented.[5] Eventually however, the former GPO was demolished and today, one of its six Doric columns still stands in Mount Street Plaza, North Sydney, whilst another can be found off Bradleys Head, Mosman.[17][18]

James Barnet's post office

First stage construction (1866–1874)

Following the demolition of the old post office, the Wynyard 'temporary' building continued to serve as the post office for ten years whilst Barnet oversaw the first stage construction of his GPO.[15] The designs which he had begun in 1863 were completed and submitted for approval in February 1865. Political changes however led to delays for the excavation and foundation works and tenders for the building's main construction did not go out until October 1866. On 17 December 1866, it was announced that builder John Young was awarded the contract for "carpenters, joiners, slaters, plumbers, painters and glaziers. His tender for masons and bricklayers was also accepted [whilst]...the commission for ironworks went to P.N. Russell and Co."[5][19]

Early progress proved to be a slow and difficult process, particularly due to the need to enclose the Tank Stream running below the foundations and to ensure construction would not affect adjoining buildings.[20] In April 1869, The Duke of Edinburgh, Alfred (later known as The Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha), second son and fourth child of Queen Victoria, set the keystone of the George Street entrance for the post office.[5][14] A prominent newspaper of the time reported that the "ponderous keystone" was quarried at Pyrmont and weighted 26 tons (26.5 metric tonnes), highlighting that it was one of many such stones used in the construction of the building and described as being "without parallel in the city."[21]

As construction works progressed, public interest and attention turned increasingly to the future of this civic structure. Shortly after the official keystone setting ceremony, on 8 September 1869, news reports began anticipating how "the building will be one of the finest specimens of architecture in the colony—a credit to the city, and a monument to the ability of the colonial Architect by whom it was designed."[22] It was also at this time that suggestions for the widening of the adjacent St. Martin's Lane began, with a newspaper commenting on 20 January 1870 that "a decent thoroughfare...would add to the architectural reputation of the city; but, without such an approach, it will probably furnish a subject for the laughter and contempt of strangers who may visit us."[5] Despite this growing public interest, significant works to transform the lane way into what is now known as Martin Place would not be discussed in government circles until 1889, near the completion of the second stage of the GPO.

The Pitt Street extension (1874–1887)

In August 1879, five years after the completion of its first stage, Barnet submitted plans for the extension of the post office. Designed to provide additional space and extend the impressive arcade further east to Pitt Street, it has since been historically noted that Barnet had conceived of this extension in as early as 1868, when stage one of the GPO was first being considered.[5]

By 1880, tenders had been called and accepted and the laying of new foundations for the Pitt Street extension had begun.[1]

Completion of the Campanile (1887–1891)

Although the construction of the Pitt Street extension was completed successfully and the building topped out by 1887, a final issue, concerning the clock tower (which Barnet referred to as a campanile) arose as a new source of disagreement. In a dispute which ran from 1887 to 1891, the bells and clock intended for the tower, originally designed by Tornaghi were declared by Barnet to be sub-standard. This was due to a disagreement between Barnet and Tornaghi over the choice of bells. Barnet preferred conventional bells while Tornaghi insisted that lighter tubular bells should be used, because he believed that the weight of conventional bells would cause the tower to collapse. Eventually, a new set of conventional bells was selected by Barnet and installed by a rival clockmaker, Henry Daly.[5]

The Post Office Bells

(With apologies to the Poet Laureate)

Ring forth, ye bells; begin to chime;

Ring in the right, ring out the wrong;

We've waited patiently and long;

Ring, welcome bells; it's nearly time.

Ring out this never-ending rain—

These floods that compass us about;

Ring in a long-protracted drought,

Till mud return to dust again.

Then, six weeks hence, when things look dry.

And thirsty meadows pray for rain,

King in the long-lost floods again—

But stop before they rise too high.

Those carvings dire, that smirk and grin,

Ring out, ring 'out without remorse;

Ring out the Cyclorama horse;

But ring the truer artist in.

Ring out the empty fools that hoot

To drown great speakers with their din;

Or, if you can't do that, ring in

The bludgeon and the heavy boot.

Ring in a Parliament of peace,

Ring out false charges, tricks unfair;

Ring in obedience to the Chair,

Ring out the all night gabbling geese.

Ring out the men who try to baulk

Those bills the country sorely needs;

Ring in a session of great deeds,

Ring out obstruction, idle talk.

Ring out our members' faults

(begin With little Parliamentary fibs);

Ring out the deficit of Dibbs,

But ring a mighty surplus in.

Ring out the members' midnight trams,

That cost the country such a sum;

Ring out the undue taste for rum

That fires some legislative lambs.

Ring out disunion; jealous blood

That fetters young Australia's might;

Ring out provincial petty spite;

Ring in a broader brotherhood.

Ring, mighty bells; make up lost time;

Ring all the changes that you know.

We want more changes here, I trow,

Than you can give: begin to chime.

Ring night and day, with clarion clang;

Ring in the good; ring out the ill;

But don't, as some folk say you will,

Ring down the tower in which you hang.

Robert Garran[23]

Whilst criticism of the carvings continued throughout the remainder of the construction, completion of the tower progressed smoothly. The finishing stone to the tower was laid in 1885. The press celebrated its completion, hailing "the ornamentation of this façade of the building is in excellent taste, and artistic skill of the highest order has been exercised in carrying the designs."[24] Barnet was however unable to attend the stone laying ceremony for this completion, as he had travelled to Europe to make important notes on art and architecture, continuing research and observations to justify the designs of the Pitt Street carvings.[25][26]

Despite the controversies surrounding the construction of the second stage, the significance of Barnet's architecture on the mindset of the colony was profound.[5][20][27] The final moment heralding the completion of Barnet's vision occurred on 16 September 1891 when the Hon. Margaret Elizabeth Villiers (née Leigh), Lady Jersey, accompanied by her husband, the then-Governor of New South Wales, Victor Child Villiers, 7th Earl of Jersey, and the Countess of Kintore, officially set in motion the clockworks at the top of the GPO Campanile.[1][28] At the time of this completion in 1891, it became subject to a publicly published poem by Australian lawyer and pioneer of the Australian federation movement, Robert Garran.

Sculpture

George Street

As well as the coat of arms, sculptural additions to the George Street façade include classical allegories. At the centre of its 100-metre (330 ft) Martin Place façade is a white marble statutory group, featuring Queen Victoria flanked by allegorical figures.

Pitt Street carvings controversy

Whilst construction of stage two progressed smoothly, the initial unveiling of what would become denigrated as the Pitt Street "caricatures" in 1883 caused great controversy throughout the city. Conceived under the supervision of Barnet and with the works executed by Italian immigrant sculptor Tomaso Sani, the sculptures were designed as "a series of high relief figures...illustrating aspects of contemporary colonial society in a realistic manner to signify the integral place of the General Post Office in colonial life."[5] The controversy over the spandrel figures resulted from their comical references to real-life personalities (including Barnet himself). Realistic portrayal was contrary to the established practices of classical allegorical figures such as those used in the first stage of the GPO. The controversy significantly affected Banet's reputation. The severity of the carvings as a matter of aesthetic taste was taken so seriously that it was raised by the then vice-president of the Executive Council of the third Parkes Ministry in the New South Wales Legislative Assembly, Sir Frederick Darley (later, sixth Chief Justice of NSW), who was shocked by what he saw and tabled questions in parliament on 12 April 1883. In defence of the carvings, fellow member of the assembly, William Dalley read out a letter written by Barnet, in which the architect argued that the carvings were "bas-relief, realistic in character, representing the men and women in the costumes of the day. This has the advantage of truth, and fix the date and historical value of the work in opposition to the allegorical or classic sculpture which could not be allied in an intelligent form to express what is intended."[29] In subsequent debates on the matter, the issues of aesthetics and beauty were raised with Dalley at one point reminding the assembly of eminent English art critic John Ruskin's declaration that "beauty should be sought in daily associations."[30]

Running parallel to the discussions in parliament, various scathing opinions were published in the press. Anonymous letters to the editor as well as prominent statements by highly respected art critics and fellow architects all offered their opinion on the state of Sani's carvings. Lorando Jones, a prominent sculptor with previous exhibitions at the Royal Academy and the Victorian Society of Fine Arts declared that "those caricatures filling the spandrels at the Post Office are alti-mezzi-relievi, and not 'bas-reliefs' as Mr. Barnet called them..."[31] His comments were however eventually disregarded as personal and bitter, given Jones had previously been refused a commission by Barnet after Jones had been convicted of blasphemy in 1871.[5] J.J. De Libra, an art critic and writer, commented that the subject matter was commendable but that it the carvings were unsatisfactory because of "the execution of the design, and the degree of the relief."[32] With the rising tide of criticism, a newspaper of the time finally lamented that Barnet "...[now] stands alone against a world of carping critics."[33]

By October 1883, the severity of the issue had led the Parkes Ministry Cabinet to appoint an independent board of experts to report on the carvings.[25] This board of enquiry reported to Barnet's superior, the Director of Public Works on 6 February 1884 and recommended that "Whilst we entirely commend the intention of Mr. Barnet in desiring to obtain of the subjects intended to be illustrated, we cannot but regret the plan and manner in which he has sought to perpetuate them...we unanimously recommend that they be cut out and that blocks of stone to be inserted, which can be decorated or not as may be thought desirable."[34] Referrals were also made to English critics, and Frederic Leighton, President of the Royal Academy in London was called upon to inspect images of the carvings. In a scathing review, formed from descriptions and photographs sent to him, he concluded that the carvings could be viewed with "nothing short of consternation and...disgust...a shameful disfigurement...ugly and degrading to the sense of sight."[5] Despite this setback, Barnet continued to reject these reports and criticisms, arguing that the photographs for study, taken on a level elevation rather than from Pitt Street, failed to correctly represent the final perspective and that the building scaffolding hindered key views to the carvings.[5]

It was also at this time that Barnet convinced editors of influential architectural publications in London to publish an article devoted to a discussion on art in New South Wales. Published on 19 September 1885, the article commended Barnet's desire for realistic sculpture but similar to previous criticisms, argued that the manner of execution was flawed.[25][35]

In 1890, whilst the bells of the GPO were finally being resolved, the long-standing issue of the Pitt Street carvings was also finally settled. In a dramatic reversal of opinion, described by the press as "astonish[ing]" and "extraordinary" the Legislative Assembly held a vote which favoured retention of the carvings by fifty-four votes to five. In an impassioned speech by assembly member Nicholas Hawken, the carvings were now acknowledged as "the beginning of art in Australia."[36] By this time however, the criticisms surrounding the carvings as well as pressures from a separate public enquiry into Barnet's handling of colonial defences had tarnished the Colonial Architect's reputation such that he had resigned from office and his department had been discreetly abolished, replaced by a reduced and reformed NSW Government Architect's Office.[5][20]

Opening ceremonies

Stage one opening (1874)

The first stage of the General Post Office building was completed in 1874 and on 1 September, a grand official opening ceremony was held with 1,500 guests, in celebration of the occasion.[14] Attended once again by Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh, the celebrations began during the evening, with a private conversazione hosted by Hercules Robinson, the then Governor of New South Wales and his wife, within the GPO itself. The room was described as "overflowing by a fashionable assemblage of ladies and gentlemen...very pleasingly and artistically adorned by magnificent works of art, flowers, plants and statues."[14][37]

The official opening ceremony speech was made by the General Post Office the Postmaster-General, (Sir) Saul Samuel who paid a glowing tribute to the work of Barnet.[20] Barnet, who was himself also present at the opening ceremony gave a speech in which he hoped that the GPO would be "taken as a sure sign of the permanent advancement of the colony and its vastly increased importance and prosperity..." and further celebrated a doubling in postage handling capacity, noting specifically in his statement to the press that the new building had a floor space of 35,247 square feet.[14][37] It was also at this time that he outlined his plans for stage two, of which the purchase of land and demolition of existing structures had already taken place. Newspapers covering the opening ceremony highlighted enthusiastically that "when the plans are fully executed, [the GPO] will not be surpassed by any similar structure in the Southern hemisphere."[37]

Stage two opening (1887)

_(2).jpg.webp)

As criticism of the carvings died down momentarily, the colonnade linking Pitt and George streets was fully opened to the public in May 1887. The public applauded the work of Barnet and demanded visions for a new civic piazza. Indeed, one newspaper illustrated an imaginary Italianate square declaring that it was "the General Post Office Square as it should be...a wide square, and the splendours of greenery and spraying fountains..."[38] As the tallest and arguably the largest civic structure in Sydney at the time, it could be seen from "all over the city" and thus, resulted in a public cry for a wider civic square to be constructed.[39] As a result of these public petitions, the Legislative Assembly passed the General Post Office (Approaches Improvement) Act, effectively permitting the government to purchase land north of the GPO for the creation of a wide public space between George and Pitt street.[4]

Additions by Walter Liberty Vernon (1898–1910s)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

The additions in the French style, with the adornment of swag around windows indicated a shift toward new trends in Australian architecture eventually becoming known as Federation Arts and Crafts movement championed by the suburban Federation Bungalow typology.

Continued development

Expansion and Royal Commission

On 2 June 1939 the Menzies government agreed to the creation of a Royal Commission to look into the £400,000 contract for extensions to the GPO.[40] On 8 June 1939 the terms of reference for the Royal Commission into the expansion works were released.[41] The enquiry was held under Justice Victor Maxwell KC[42][43] with the final report given in September 1939[44] finding "no suspicion of bribery or dishonesty of any sort".[45][46]

Wartime changes (1940–1996)

| External videos | |

|---|---|

The clock tower was disassembled in 1942 to reduce the visibility of the GPO in case of an air attack on Sydney. It was rebuilt in 1964.

When the clock was retrieved from storage in 1964, an "Eternity" inscription by Arthur Stace was found written in chalk inside the bell. It was left there and is now one of only two original Eternity inscriptions.

Refurbishment and current use (1996–present day)

Having remained as the headquarters of NSW postal system since its completion, the GPO was privatised and leased out in 1996 as part of the disbursement of assets by the Federal Government of Australia. It was refurbished through the work of Sydney-based architectural practice Clive Lucas Stapleton & Partners and subsequently the building houses shops, restaurants, hotel rooms, and the foyer of two adjoining tower blocks.[48] The refurbishment was completed in September 1999 to coincide with the 2000 Sydney Olympic Games. In 2019, cleaning and remediation of the facades and sculptures was undertaken by the building's owners.[49]

In the now heritage GPO building, Australia Post maintains a presence in the form of a "Post Shop" at the corner of Martin Place and George Street but the rest of the building is devoted to shops, cafes, restaurants and bars as well as a hotel and function rooms. The Fullerton Hotel and Macquarie Bank office towers stand behind the former courtyard, which was converted into an atrium.[50] The ground and lower ground floors house retail premises with the anchor tenant operating all the food and beverage operations known collectively as the "GPO Grand" (GPO Restaurants and Bars).[51]

Clock

The clock—"a three-train flatbed clock with gravity escapement"—was originally made in the United Kingdom and installed in 1891, but its hands were turned by an electric motor since 1989. In 2020 the clock underwent a major refurbishment involving repairs to the glass, stone and metalwork, as well as the mechanism. The intention was to maintain its heritage, make the clock accurate, and have it play a full Westminster chime like Big Ben.[52]

Ownership

With the merger of the colonial postal services, the GPO building was transferred to the federal Postmaster-General's department ("PMG") in 1901 after Federation. It remained in the ownership of the federal postal authority (now Australia Post), although following the 1996 conversion the building was leased for 99 years to Singapore-based Far East Organisation and its affiliate Sino Land Company, which own the adjoining luxury 5 star 416 room Fullerton Hotel Sydney. In July 2017 Australia Post announced that the freehold over the building had also been sold to Far East Organisation and Sino Land. The sale process has been criticised as secretive and offering inadequate protection for the significant historical building.[53] An "updated heritage management plan" was included in the sale and Australia Post said it would seek National Heritage listing for the newly sold building "in recognition of its historical importance and to reinforce existing heritage protections".[54] Criticism of the sale described it as simply "asset stripping" and referred to the government's lack of care of the city's heritage and its past, as well as doubts over the new owners' ability to protect the building in the future.[55] Sino Land, which is the sister company of Far East Organisation, is also notable for acquiring and owning The Fullerton Hotel Singapore, which was formerly the General Post Office of Singapore from 1928 to 1996. The iconic hotel is notable for being the prominent feature on Singapore's city waterfront. The hotel was gazetted as a conservation building by the Government of Singapore in 1997, prior to its sale to Sino Land. Beginning in April 2019, Sino Land had Stonemason and artist, Leichhardt, extensively clean the GPO facades and sculpture. In September when the hoarding was removed the sandstone sculpture appeared bleached and white, but slowly regained an unnatural uniform insipid grey colour that was artificial and quite unlike the beautiful warm colour of natural sandstone.

Architecture

Arcade

The columns and base which form the arcade of the General Post Office is constructed of high quality polished granite taken from the Louttit Quarry on the Moruya River, the general effect of which was "much admired".[56] True to Barnet's intentions, it had its inspiration in the Italian public buildings of Bologna, Vicenza and Venice.[15][37] Barnet preferred to use local materials wherever possible, rather than import "foreign materials". The use of granite rather than sandstone was also the result of structural needs, which Barnet himself during the opening ceremony described as being "necessitated by the immediate weight which was super-incumbent on small points of support, to form the arcade.[37] The sandstone which was carved from Pyrmont to form the mezzanine galleries and spandrels of the arcade were done in sizes which had never been attempted in Australia and the internal domed vaults demonstrated Barnet's innovative use of fireproof concrete.[37] The keystones along the arcade features exquisitely carved allegorical faces representative of the dominions within the British Empire and other foreign nations.

Historians have since noted that Barnet's design was an "eminently practical solution" which not only increased pedestrian access and a transition between exterior and interior of the building, but also gave the façade a sense of depth and character.[5] The introduction of a colonnade, at the time of its completion, doubled the width of St. Martin's Lane from three to six metres, allowing also for the transfer of goods and delivery of mail efficiently and effectively.[4] Architecturally, the arcade became a mediating type, not only for the street which would eventually become Martin Place, but also allowed Barnet to establish repetition and a sublimity of human proportion and scale.[20][57]

_John_Sharkey._(9832042033).jpg.webp)

Facade articulation

When the GPO was first opened to the public 1874, Barnet confirmed, in a statement to the press that "The style chosen for the design is Italian Renaissance, and was necessarily adapted to the uses of the building and the nature of the site."[37] The building has been variously identified as a form derived from a filtered Classicism with its roots in the Renaissance. In particular, its free use of Classical motifs finds its roots in the works of English architect and historian Charles Robert Cockerell.[58] Today, the style in which the façade has been articulated is variously identified as Victorian Free Classical or the Italian Renaissance Palazzo Style.[1] The three major street-facing facades all consist of a tripartite articulation and is composed from load bearing Sydney sandstone, supported by the granite columns which form the Martin Place arcade. Professor of Architecture at the University of Sydney, Leslie Wilkinson, commented that Barnet had high regard for these materials as "it could be quarried in very large blocks completely free of flaws."[5]

At the centre of its 100-metre (330 ft) Martin Place façade is a white marble statuary group, featuring Queen Victoria flanked by allegorical figures. Above this stands the clock tower.

Interiors

.jpg.webp)

The reworking of the interior retained the vast majority of the building's highly significant wrought iron and coke breeze arched structure. Large spaces in the upper levels were subdivided into hotel rooms. A 1920s building that housed the main postal hall enclosed by the Victorian era building was demolished, the 1922 Postal Hall reconstructed and a long span steel frame and glass roof structure added to seal a large atrium for the hotel. Some of the original internal courtyard facade elements demolished for the 1920s building were also reconstructed.

Relationship to Martin Place

It has been said by several influential architectural historians that the development and creation of Martin Place stems greatly from the construction of the General Post Office. When Barnet was first commissioned to build the new post office, the main façade faced George Street and the colonnade faced a tiny lane only 3 metres (9.8 ft) wide.[39] Through the articulation of the northern façade, with a well maintained continuity in proportion between the three types of openings along the levels of the GPO generated a harmonious module which allowed the full sense of grandeur to be realised. The use of government funds was granted so that land was purchased north of the GPO to provide an "appropriately scaled civic setting for the GPO."[4] Barnet's deliberate insertion of an arcade, proportional intents and the centring of the campanile along what was once a lane way were all architectural moves designed to develop a space which would link Pitt and George Streets. Some argue that Martin Place "was never planned. Nor was it entirely accidental"; rather the public square evolved through a "serendipitous mixture of architectural flair, public debate and individual determination."[39]

Others have however been more certain in the relationship between Martin Place and the GPO, saying for example that Barnet's "understanding of civic propriety and of the role of public buildings coincided with the Victorian concept of decorum: civic order and urban legibility established through public buildings."[30] In this view, the GPO and the subsequent construction of Martin Place show the "power of the building's presence to force the clearing of lesser buildings, to create a public space, reinforces this as does the design of a facing building that clearly understood its need to be complementary and referential."[27] It has been argued that the granite and sandstone arcade offers a transition between the public domain and interior spaces of the GPO, where a strong presence which "forced the clearing of lesser buildings" generates a public square.[30] The existence of Martin Place is largely "owed to the construction of the General Post Office"; Barnet knew changes would be made "because the completed building would clearly lack what was appropriate to it, a dignified square."[57]

See also

- Clarion Hotel Post, former post office now hotel, in Gothenburg, Sweden.

- Architecture of Sydney

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "General Post Office". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Department of Planning & Environment. H00763. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence. - 1 2 "General Post Office, No. 1 Martin Place, Sydney, NSW (Place ID 105509)". Australian Heritage Database. Australian Government. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- 1 2 "General Post Office, 1 Martin Pl, Sydney, NSW, Australia (Place ID 1836)". Australian Heritage Database. Australian Government. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Thalis, Philip; Cantril, Peter John (2013). Public Sydney: Drawing the City. Sydney, Australia: Historic Houses Trust and Content, Faculty of Built Environment, University of New South Wales, Australia. pp. 112–117. ISBN 9781876991425.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Bridges, Peter; McDonald, Don (1988). James Barnet: Colonial Architect. Sydney, Australia: Hale & Iremonger Pty Ltd. ISBN 0868062936.

- ↑ Bridges, Peter (1988). the City's Centrepiece: the history of the Sydney G.P.O. Marrickville, NSW: Hale & Iremonger Pty Ltd. pp. 51–57. ISBN 0868063045. OCLC 19512570.

- ↑ Scarlet, Ken (1980). Australian Sculptors. Melbourne, Australia: Thomas Nelso Australia Pty Ltd. pp. 579–582. ISBN 0170052923. OCLC 6943806.

- 1 2 Johnson, Chris (2000). Bingham-Hall, Patrick (ed.). James Barnet: The Universal Values of Civic Existence. Sydney, Australia: Pesaro Architectural Monographs. pp. 32–40. ISBN 0957756038.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ Orr, Kirsten (2007). "The Sydney General Post Office: A Metaphor for Australian Federation" (PDF). LIMINA: A Journal of Historical and Cultural Studies. 13. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

- ↑ "Sydney GPO Post Shop". Australia Post. Archived from the original on 8 October 2015. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- ↑ "Eora: Mapping Aboriginal Sydney 1770–1850" (PDF). State Library of New South Wales. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 11 August 2015.

- 1 2 McDonald, Ewen (2012). Site. Sydney, Australia: Museum of Contemporary Art Limited. p. 74. ISBN 9781921034565.

- ↑ "Indigenous People of Sydney". Royal Botanic Gardens & Domain Trust. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 11 August 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Johnston, D. L. (1966). An Investigation into the History of Buildings attributed to James Barnet, Colonial Architect from 1865 to 1890. (Thesis in Bachelor of Architecture, Honours at the University of New South Wales, Australia). Sydney, Australia. pp. 28–38.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - 1 2 3 4 5 Ellmoos, Laila. "The General Post Office". Dictionary of Sydney. Archived from the original on 6 October 2015. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- ↑ "Report from the Board of Enquiry on the General Post Office". NSWLC. 3. 1851.

- ↑ "Set in stone" (PDF). North Sydney City Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 September 2007.

- ↑ Carment, David (2011). "Bradley's Head". Dictionary of Sydney. Archived from the original on 26 March 2017. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- ↑ "Contracts Entered into for the Erection of the New General Post Office". New South Wales Government Gazette. 20 December 1867. p. 17.

- 1 2 3 4 5 McDonald, D.I. Barnet, James Johnstone (1827–1904). National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Archived from the original on 10 December 2015. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ↑ "The New Post Office". The Sydney Morning Herald. 2 April 1869. p. 5. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ↑ "Public Works". The Sydney Morning Herald. 8 September 1869. p. 8. Retrieved 17 October 2015 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "The Post Office Bells". Evening News. Trove – National Library of Australia. 30 June 1891. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- ↑ "The Extension of the Post Office Buildings – Completion of the Stonework". The Sydney Morning Herald. 2 October 1885. p. 12. Retrieved 1 November 2015 – via Trove.

- 1 2 3 Johnson, Chris (2000). Barnet and Australian Identity: Universal or Local, Imported or Native?. Sydney, Australia: Pesaro Architectural Monographs. pp. 32–39. ISBN 0957756038.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ "The Colonial Architect". The Sydney Morning Herald. 22 January 1885. p. 5. Retrieved 1 November 2015 – via Trove.

- 1 2 Johnson, Chris (1997). Gates, Colonnades & Carvings – Barnet's Architecture of Representation: A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Master of Architecture, History and Theory. Sydney, Australia: The University of New South Wales.

- ↑ "Social Events". The Sydney Morning Herald. 21 September 1891. p. 4. Retrieved 1 November 2015 – via Trove.

- ↑ "Parliament of New South Wales – Legislative Assembly, Thursday 12 October 1883 – The Carvings at the General Post Office". The Sydney Morning Herald. 13 October 1883. p. 2. Retrieved 31 October 2015 – via Trove.

- 1 2 3 Johnson, Chris (1999). Shaping Sydney: Public Architecture & Civic Decorum. Sydney, Australia: Hale & Iremonger. pp. 80–83, 100–104. ISBN 0868066850.

- ↑ Jones, W. Lorando (19 April 1883). "The Post Office Carvings". The Sydney Morning Herald. p. 7. Retrieved 1 November 2015 – via Trove.

- ↑ de Libra, J. J. (20 April 1883). "The Carvings on the Post Office – to the Editor of the Herald". The Sydney Morning Herald. p. 3. Retrieved 15 January 2016.

- ↑ "To hold as twere the mirror up to nature. Our Illustrations". Illustrated Sydney News. 15 June 1886. p. 3. Retrieved 15 January 2016.

- ↑ "The Post Office Carvings". The Sydney Morning Herald. 12 February 1884. p. 5. Retrieved 1 November 2015 – via Trove.

- ↑ "The Post Office Carvings". The Sydney Morning Herald. 30 October 1885. p. 3. Retrieved 1 November 2015 – via Trove.

- ↑ "The Legislative Assembly". The Sydney Morning Herald. 17 December 1890. p. 5. Retrieved 1 November 2015 – via Trove.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Opening of the New Post Office". The Sydney Morning Herald. 2 September 1874. p. 6. Retrieved 19 January 2016 – via Trove.

- ↑ "General Post Office Square, as it should be". Illustrated Sydney News. 26 January 1888. p. 22. Retrieved 1 November 2015.

- 1 2 3 Meacham, Steve (1 October 2007). "A city's heart builds on a sense of place". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- ↑ "MENZIES MINISTRY HAS TRYING DAY". The Telegraph. 2 June 1939. Retrieved 30 December 2022 – via Trove.

- ↑ "ROYAL COMMISSION". Dubbo Liberal and Macquarie Advocate. 8 June 1939. Retrieved 30 December 2022 – via Trove.

- ↑ "SYDNEY G.P.O. CONTRACT". Australian Worker. 14 June 1939. Retrieved 30 December 2022 – via Trove.

- ↑ "Hon. Allan Victor [I] Maxwell CMG". NSW State Archives & Records.

- ↑ "Royal Commissions and Commissions of Inquiry". aph.gov.au. Parliament House, Canberra. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- ↑ "No Suspicion of Bribery Rules Royal Commission in Sydney G.P.O. Report". The Telegraph. 29 July 1939. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- ↑ "Royal Commission regarding the contract for the erection of additions to the General Post Office, Sydney [1939] AURoyalC 1 (22 September 1939)". austlii.edu.au. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- ↑ Removal of the Sydney GPO Clock Tower (1942). National Archives of Australia. C4189/1.

- ↑ "No. 1 Martin Place – Sydney GPO". Clive Lucas Stapleton & Partners – Architects & Heritage Consultants. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- ↑ Barlass, Tim (19 April 2019). "GPO's 'petrified marionettes' get facelift from new hotel owner". The Sydney Morning Herald.

- ↑ "No. 1 Martin Place". The Westin Sydney. Archived from the original on 6 July 2007. Retrieved 22 March 2007.

- ↑ "GPO Grand website". Archived from the original on 13 November 2018. Retrieved 11 December 2018.

- ↑ Barlass, Tim (16 July 2020). "Look no hands as Sydney's GPO clock gets a makeover". The Sydney Morning Herald.

- ↑ "Sydney GPO site signed and delivered to Singaporean joint venture". The Australian. 27 July 2017. Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- ↑ Evans, Michael (26 July 2017). "Australia Post confirms sale of historic Sydney GPO, seeks heritage listing". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 30 July 2017. Retrieved 30 July 2017.

- ↑ Farrelly, Elizabeth (29 July 2017). "GPO endgame: Sale of most loved building to Singaporean billionaires an asset strip". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 29 July 2017. Retrieved 30 July 2017.

- ↑ Baker, Richard Thomas (1908). Building and Ornamental Stones of New South Wales Franco-British Exhibition, London, 1908. Sydney, NSW: Dept. of Public Instruction. p. 20.

- 1 2 Kohane, Peter (2000). Bingham-Hall, Patrick (ed.). James Barnet: The Universal Values of Civic Existence. Sydney, Australia: Pesaro Architectural Monographs. pp. 10–21. ISBN 0957756038.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ Apperly, Richard; Irving, Robert; Reynolds, Peter (1995). A Pictorial Guide to Identifying Australian Architecture. Sydney, Australia: Angus & Robertson. pp. 56–59. ISBN 020718562X.

Bibliography

- "Commerce Walking Tour". 2007.

- Attraction Homepage (2007). "Commerce Walking Tour" (PDF).

- Biddulph, C. L. (1874). "The GPO Waltz – dedicated to "The Hon., The Post Master and his staff"".

- Burn, J. S. (1967). The General Post Office. National Trust Listing Card.

- Clive Lucas, Stapleton & Partners Pty Ltd (1991). General Post Office Sydney. Conservation Analysis and Draft Conservation Management Plan.

- Le Sueur, Angela; Quint, Graham (2017). 'Trust Action: Sale of Sydney's GPO Building: a national disgrace'.

Attribution

![]() This Wikipedia article contains material from General Post Office, entry number 763 in the New South Wales State Heritage Register published by the State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) 2018 under CC-BY 4.0 licence, accessed on 13 October 2018.

This Wikipedia article contains material from General Post Office, entry number 763 in the New South Wales State Heritage Register published by the State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) 2018 under CC-BY 4.0 licence, accessed on 13 October 2018.

External links

- GPO Sydney Archived 7 January 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- Ellmoos, Laila (2008). "General Post Office". Dictionary of Sydney. Dictionary of Sydney Trust. Retrieved 10 October 2015. (CC-By-SA)

- "Royal Commission regarding the contract for the erection of additions to the General Post Office, Sydney [1939] AURoyalC 1 (22 September 1939)". austlii.edu.au. Retrieved 30 December 2022.