| Chinese Garden of Friendship | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Chinese Garden of Friendship | |

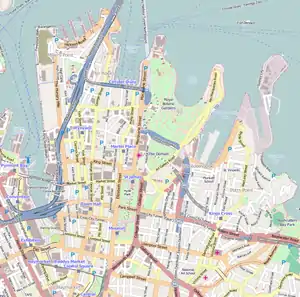

Location in the Sydney central business district | |

| Type | Chinese garden |

| Location | 1 Harbour Street, Sydney central business district, City of Sydney, New South Wales, Australia |

| Coordinates | 33°52′35″S 151°12′10″E / 33.8765°S 151.2028°E |

| Area | 1.03 hectares (3 acres) |

| Created | 1986–17 January 1988 |

| Designer |

|

| Operated by | Place Management NSW |

| Visitors | 230,000 (2016–17) |

| Status | Open all year |

| Official name | Chinese Garden of Friendship |

| Type | State heritage (complex / group) |

| Designated | 5 October 2018 |

| Reference no. | 2017 |

| Type | Other – Landscape – Cultural |

| Category | Landscape – Cultural |

| Builders |

|

| Chinese Garden of Friendship | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 誼園 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 谊园 | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

The Chinese Garden of Friendship (simplified Chinese: 谊园; traditional Chinese: 誼園) is a heritage-listed 1.03-hectare (3-acre) Chinese garden at 1 Harbour Street, in the Sydney Central Business District, City of Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. Modelled after the classic private gardens of the Ming dynasty, the garden offers an insight into Chinese heritage and culture. It was designed by Guangzhou Garden Planning & Building Design Institute, Tsang & Lee, and Edmond Bull & Corkery. It was built between 1986-1988 by Gutteridge Haskins & Davey, the Darling Harbour Authority, Imperial Gardens, Leightons, and Australian Native Landscapes. The gardens were added to the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 5 October 2018.[1]

The Chinese Garden of Friendship was designed by Sydney's Chinese sister city, Guangzhou. Its proximity to Sydney's Chinatown complements the area's already rich Chinese heritage and culture. The garden was officially opened 17 January 1988 as part of Sydney's Bicentennial Celebrations and named the Chinese Garden of Friendship symbolising the bond established between China and Australia.

The garden is located at the corner of Day Street and Pier Street, Darling Harbour, the former site of NSW Fresh Food and Ice Co.[2]

History

Prior to colonisation the site was open water adjacent to a low-lying swampy area. From about 1850 to 1984 the site was filled-in and used as industrial land.[1]

The land that would become the Chinese Garden of Friendship is in Cockle Bay and was progressively reclaimed and industrialised from the early years of the 19th century. Industries included ship building and repairs around the edges of the water, while further inland predominant uses were engineering workshops, metal foundries and food milling factories.[1]

The site was first developed by Mort's Fresh Food & Ice Company in the 1850s known for its internationally significant developments in refrigeration technology. Light industrial buildings on the site and in its vicinity were demolished in 1985 as part of the Bicentenary redevelopment of Darling Harbour. This site history is uncommon for overseas Chinese gardens, which are typically located in existing parklands. The exception is several gardens in Hong Kong that were built in the 1970s–80s on reclaimed waterside industrial land.[1]

The Landscape Section of NSW Public Works, Government Architect's Branch, was directly involved in development and construction of the garden. Oi Choong, then Head of the Landscape Section, noted that along with the Mount Tomah Botanic Garden, the Australian Botanic Garden Mount Annan and Bicentennial Park, Homebush Bay, the Chinese Garden of Friendship is one of the few seminal landscapes built to celebrate Australia's bicentenary.[1]

Henry Tsang OAM, a leading figure in Sydney's Chinese community, a member of Sydney City Council (1991–1999), and the New South Wales Legislative Council (1999–2009), advocated for the establishment of a Chinese garden in Sydney since the 1970s. At that time, overseas Chinese gardens were first established in Hong Kong and Singapore. In the early 1980s, the grounds of Sydney's two oldest Chinese temples (Tze Yup temple in Glebe, and Yiu Ming temple in Alexandria) were embellished with new boundary walls and pailou (gates). At the same time, the local Chinese community in British Columbia had succeeded in having a Chinese garden established in Vancouver, which opened in 1982.[1]

With the announcement in 1984 of the bicentenary redevelopment of Darling Harbour, the local Chinese community lobbied the NSW government for a garden site in Darling Harbour. Tsang approached Neville Wran, the premier of New South Wales (1976–1986), to allocate an area of crown land for a traditional Chinese garden to celebrate the role of the Chinese community in developing Australia's commercial and social structures since the early 19th century. Tsang and the local Chinese community were able to secure from Wran a site adjacent to Chinatown in Haymarket and helped facilitate an intergovernmental relationship between the Province of Guangdong and State of New South Wales to jointly fund, design and construct the new garden.[1]

The relationship between Sydney and Guangzhou (historically called Canton in English), the capital of Guangdong province, is particularly strong because of trade and migration since the earliest days of colonisation. The agreement stipulated Guangdong would provide the design of the garden and key building materials, furniture and artworks that are intrinsic to the classic garden typology, while New South Wales would manage and fund its construction through the Darling Harbour Authority.[1]

There is considerable documentation of the challenges with building the garden, from the initial Cantonese concept drawings, their conversion into Australian-style construction drawings, sourcing local trades people with the skills to undertake very unusual construction methodologies, finding suitable local building materials, importing special materials from China such as artworks, furniture, tiles and feature rocks, and the politics of Chinese working on the site within the strict union rules and regulations of the time.[1]

The Chinese Garden of Friendship formally opened to the public in 1988 during the Bicentennial celebrations. The Bicentennial celebrations strongly focused on Australia's achievements as a multi-cultural society with an official theme of "Living Together". It was the first such garden in the southern hemisphere, the second in an English-language settler society after Vancouver, and among the earliest in the world.[1]

Launching The Chinese Garden of Friendship's 30th Anniversary in 2018, the initiative of Minister Victor Dominello with the Chinese Gardens Advisory Panel welcomed key community leaders and representatives to celebrate Chinese New Year during a magical auspicious evening that marks CNY in one of the city's key cultural places. 2018 will see the garden's planned development plans and community collaboration in building a prosperous future for the gardens. The gardens held a festival to celebrate 30-year anniversary with events between 29 September to 14 October 2018.[1]

On 4 October 2018, Dominello, as Minister for Services and Property, used an event celebrating the garden's 30th anniversary as an opportunity to announce that Gabrielle Upton, the minister for heritage, had recently added the place on the State Heritage Register. The event was well attended by the Heritage Council with the Chair, Deputy Chair, Mark Dunn, Louise Cox, Bruce Pettman, and with Prof Richard Mackay amongst a strong Chinese community presence.[1]

Description

The garden is a designed landscape largely enclosed by a masonry wall, covering 1.03 hectares (3 acres) in area. This area is composed of three main elements:[1]

- garden landscaping, 5,700 square metres (61,000 sq ft)

- lake and streams, 3,300 square metres (36,000 sq ft)

- pavilions and other structures, 1,300 square metres (14,000 sq ft)

The site includes the forecourt entrance stairs, two imperial guardian lion (or ski) statues and plantings of Chinese elms (Ulmus parvifolia), all of which adjoin the garden wall outside the garden proper.[1]

The garden design is a built and horticultural expression of a private garden, sometimes described as a scholar's or classical garden.[1]

Garden typologies created over the last thousand years from the Song to the Qin dynasty demonstrate many historical, philosophical and regional variations. For instance, the cold climate Northern garden styles favour deciduous plant species and an urban character, while the warmer temperate climates of the Southern styles are marked by lusher sub-tropical plantings. Southern styles are sometimes called Cantonese, from their associations with Guangdong, Guangxi and Hainan provinces and Hong Kong and Macau, or Lingnam, meaning "south of the mountains", referring to the region's location south of the Five Ranges of the Yangtze Valley. Generally, a private garden is a place of retreat and reflection, poetry, art, calligraphy and horticulture.[1]

The Garden of Friendship design weaves the principles of auspicious positioning and orientation to channel positive qi energy through the garden; provides a preferred large and central water body to capture positive energy otherwise expressed as wealth and prosperity; demonstrates the placement of landforms to block unfavourable weather while opening the garden to the positive movement of the sun; places pavilions around the water body to reflect upon and disseminate the positive energy stored within the water body; and establishes key visual connections between the host and guest pavilions and landscape. A 2004 feng shui assessment of the garden considered it as a reflection of these design principles and as an embodiment of the five elemental relationships between water, earth, air, wood and steel.[1]

This process of "translation", in which a Southern-style garden was recontextualised in the setting of the new Darling Harbour development, brought together a unique fusion of Cantonese and Sydneysider styles, materials, artisanship and horticultural practices. In the spirit of "translation", the garden's plantings have evolved greatly since that time. It was very raw when opened and being a new landscape was overplanted in the expectation that natural losses would occur. It has prospered, and over time plants have been removed to give others around them room to expand, and to preserve particular visual connections.[1]

Like any living garden, the Garden of Friendship is continually changing, and these dynamic processes are actively managed to retain the original design, spirit, and integrity while allowing its evolution in response to climatic and social changes, and the natural life cycles of living plants.[1]

Key elements within the townscape setting for the Garden of Friendship are Tumbalong Park and Tumbalong Boulevard. Tumbalong Park is a key link in the qi line from the garden to Cockle Bay, while the boulevard is the effective buffer between the garden and the very large International Convention Centre Sydney structures. The qi line has been marked since 2017 by a bronze strip across the stage in Tumbalong Park symbolically linking the garden with the parkland and the waters of Darling Harbour.[1]

The garden wall

The garden is enclosed by a white painted, rendered masonry wall on three sides (south, east and north). The wall is approximately 4 metres (13 ft) in height and capped with scroll styled terracotta tiles. The western side is defined by a palisade fence transitioning to a mixed water and pavilion edge. The palisade fence is atypical but included so passing pedestrians can see into and be attracted to visit the garden. This "open" fence also has a very important role in the feng shui of the garden, allowing the qi energy to move from the garden towards Cockle Bay.[1]

Forecourt

The garden entrance has stairs and podiums with two imperial guardian lion (or shi) statues protecting the entrance, one male and one female. Some ceramic trays (pen or pun) and some specimen stones, are from Guangdong.[1]

Pavilions

There are 17 pavilions in the garden, some interconnected, others are free standing, constructed with components from both China and Australia, including:[1]

- grey roof tiles (Guangdong)

- golden glazed roof (Guangdong)

- Gurr pavilion, granite paving and handrails (Guangdong)

- grey bricks (from Guangdong, recycled from demolished historic buildings). The bricks were refurbished and polished in China.

- grey floor tiles (Shanghai)

- grey ceramic door and window reveals (Shanghai)

- ceramic grills (Shanghai)

- granite column bases, margins, cladding, handrails, paving and door frames (Fujian)

- geometric timber tracery, and other structural elements (New South Wales)

Pavilion artworks

All art including calligraphy, wall hangings and paintings are a gift from the government of Guangdong.[1]

Pavilion furniture

All traditional furniture pieces are a gift from Guangdong, while the recent addition of a display cabinet in the Water Pavilion was designed and built in New South Wales.[1]

Water

The water bodies including the lake, pond and brooks, are constructed with a concrete base liner. The waterfall rockwork is sprayed concrete over a wire formwork, similar to the technique used in the artificial grottoes in the animal enclosures at Taronga Zoo, Mosman. Water is recycled, filtered and UV treated similarly to a public fountain system.[1]

Garden rock

All general landscape rock is water-weathered fossiliferous limestone from an ancient river bed, excavated from Cumnock Station, in Cabonne Shire, NSW Central West. In China, similarly water-worn rock was very highly prized in gardens, often coming from Lake Tai. This represents a local variation in material on a traditional pattern of use.[1]

Garden granite bridges

All stone bridges are granite from Guangdong, China.[1]

Featured rock sculptures

- Ying rocks in the Courtyard of Welcoming Fragrance are weathered limestone quarried from the mountains of Yingde, a district in south Guangdong

- Ying rock sculptured mountain and stairs to the Tea House are from Yingde in China

- Taihui rock in the garden of the Hall of Longevity is a rare weathered limestone from Lake Tai in China and a gift from Guangdong

- Wax rock in paved courtyard of Hall of Longevity is a rare river-moulded rock and a gift from Guangdong.[1]

The Dragon Wall

The Dragon Wall is a double sided, free-standing screen made of glazed terracotta from China, commissioned specifically for this garden and a gift from the government of Guangdong. The wall depicts a blue dragon representing New South Wales and a brown dragon representing Guangdong, both are in search of the pearl of wisdom. The wall design is based on the "nine dragon walls" in Datong, Shangxi. The wall was manufactured by Shiran Glazed Pottery in 943 pieces and assembled on site by potters from China.[1]

The main, or Mountain Gate

This gate was a gift from the government of Guangdong.[1]

Landscape paving

All paving including pebble mosaics are supplied and laid by New South Wales contractors. The mosaic patterns are both decorative and suggest a natural stone scree found along the edges of lakes and rivers.[1]

Planting

All plants were sourced in New South Wales, including Australian and exotic species. There are two lychee trees (Litchi chinensis) that were planted by visiting governors of Guangdong province in 2009 and 2015. Lychee is one of the "four great fruits of Lingnan", along with banana, pineapple and paw paw.[1]

Penjing (kV) collection

Penjing (Chinese: 盆景) roughly translates as "landscapes in a tray" or "tray scenery". It focuses on creating a miniature landscape of trees and rock, sometimes with added figurines and landscape elements such as bridges, pavilions and farm animals. The collection commenced in 1992 and is largely created in the Cantonese or Lingnan style of penjing, which is particular to Guangdong and Guangxi provinces. This style pays particular attention to matching the natural and artificial elements, such as plant and pot.[1]

There are 17 individual examples in the collection, composed of 13 different species including two Port Jackson figs (Ficus rubignosa).[1]

Ages of individual penjing, where known, range from 12 years to about 70 years. All have been cultivated and styled in Sydney by penjing artists. Two very old and well regarded penjing were sent from Guangdong as a gift in 1988, but they did not survive the quarantine fumigation process. Some of the ceramic trays (pen or pun), and some of the specimen stones, are from Guangdong. The penjing collection is owned by the Crown through Place Management NSW.[1]

Condition

As at 6 June 2018, the condition of the gardens' fabric was good to excellent; and the archaeological potential was moderate to high. The integrity of the site was excellent. Overall, the garden is little changed since construction. The plantings have matured considerably since 1988 and have at times affected key visual connections between various elements. General maintenance and considered interventions are addressing these matters over time.[1]

Modifications and dates

- 2005: Conversion of the Blue Room (pre-2005 it was used as a cafe), located above the current cafe seating area, due to poor access. The Blue Room remains in original condition and is now used as a meeting room and for internal staff activities only. As of 2018, it was not accessible to the public.[1]

- An original memorabilia shop was converted into the current cafe. To build a new kitchen, a small open courtyard at the back of the shop, where the penjing collection was originally displayed, was demolished. The penjing collection was relocated to the Courtyard of Welcoming Fragrance as the garden entry.[1]

- The forecourt was remodelled to accommodate an access ramp for those with a disability, and generally enlarged to the west to give the entrance more presence in the broader Darling Harbour landscape.[1]

- In 2013, the public toilet along the southern wall was internally renovated. There was no change in its footprint.[1]

- The pavilions are in original condition. Ongoing maintenance has focussed on painting and minor repairs only.[1]

In popular culture

The garden was used as a scene for Dulcea's compound in 20th Century Fox's 1995 superhero film Mighty Morphin Power Rangers: The Movie and also in the filming of The Wolverine in October 2012.[3] Although many features of the gardens were changed or covered up as the movie was set in Japan – removal of all Chinese calligraphy and dragon motifs and a temporary pavilion built in the centre of the lake.

Heritage listing

As of 6 August 2018, The Chinese Garden of Friendship is state significant as an outstanding exemplar of a community-based late overseas Chinese garden. It was the first Southern or Cantonese style garden in New South Wales developed cooperatively between Sydney's Chinese communities and public authorities in New South Wales and Guangdong.[1]

The garden demonstrates living traditions of over a thousand years in formal garden design and making in China and long continuities of particularly Southern, formal garden design and horticultural practices. It transcends boundaries between Cantonese cultural sensibilities within Sydney's urban context. Its penjing collection of miniature landscapes, cultivated in Sydney, diverse in their use of indigenous plant species such as the Port Jackson fig as well as species from China. The collection's cross-cultural significance is enhanced by geometric timber tracery screens and open-sided pavilions copied from historic Sydney models as a conscious expression of Chinoiserie. They provided a degree of popular familiarity and receptivity to Chinese gardens that hailed the construction of this garden.[1]

The garden is a unifying element tying the larger scale of the new Darling Harbour and older, more intimate spaces of Haymarket's streets and lanes. The continuing development of Sydney's Chinese communities are reflected in its Southern Chinese design and artisanship, in conjunction with Sydney and New South Wales' materials and construction. The garden provides continuity to a landscape rooted in the ever-more sophisticated Haymarket Chinatown of which it is now a distinct quarter.[1]

The garden symbolises the welcoming of Australian-Chinese communities into New South Wales and Australian society. It represents the successful collaboration of Cantonese and Sydney designers, technicians and tradesmen and the transfer of traditional skills and techniques. It is a unique example of cross-cultural exchange in the construction of built and landscape forms that clearly demonstrate the rich heritage of Guangdong and Southern China translated into a new and unique garden enjoyed by the whole community.[1]

Chinese Garden of Friendship was listed on the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 5 October 2018 having satisfied the following criteria:[1]

- The place is important in demonstrating the course, or pattern, of cultural or natural history in New South Wales.

- The place is important in demonstrating aesthetic characteristics and/or a high degree of creative or technical achievement in New South Wales.

- The place has a strong or special association with a particular community or cultural group in New South Wales for social, cultural or spiritual reasons.

- The place possesses uncommon, rare or endangered aspects of the cultural or natural history of New South Wales.

Gallery

Waterfalls in the garden

Waterfalls in the garden Entrance to the garden

Entrance to the garden Statue at the entrance

Statue at the entrance Fish pond in the garden

Fish pond in the garden

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 "Chinese Garden of Friendship". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Department of Planning & Environment. H02017. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence. - ↑ "Chinese Garden of Friendship Statement of Significance". NSW Property. Government of New South Wales. Archived from the original on 21 March 2020. Retrieved 16 August 2016.

- ↑ "Filming Location Matching "Chinese Garden of Friendship, Darling Harbour, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia" (Sorted by Popularity Ascending)". IMDb. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

Bibliography

- Beattie, James (2007). 'Growing Chinese Influences in New Zealand Chinese Gardens: Identity & Meaning'.

- Brash, Carol (2011). 'Classical Chinese Gardens in Twenty-First Century America: Cultivating the Past'.

- Campbell, Duncan (2011). 'Transplanted Gardens: aspects of the design of the Garden of Benificence, Wellington, New Zealand'.

- Choy, Howard, Feng Shui Architects (2004). Report of Feng Shui Analysis and Conceptual Advice.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Commonwealth of Australia (Australian Heritage Commission: publisher) (2002). Tracking the Dragon: A guide for finding and assessing Chinese Australian Heritage Places.

- Li, Han (2015). 'From the Astor Court to Liu Fang Yuan: Exhibiting 'Chinese-ness' in America'.

- Hodges, Sue (2012). Interpretation Strategy 2012: Chinese Garden of Friendship.

- Cheng, Ji (1988). The Craft of Gardens.

- McCormack, Terri (2008). "'Chinese Garden of Friendship'".

- Missingham, Dr Greg (2007). Japan: 10+, China: 1: a first attempt at explaining the numerical discrepancy between Japanese-stype gardens outside Japan and Chinese-style gardens outside China.

- Nowland, Peter (Sydney Harbour Foreshore Authority) (2012). The Chinese Garden of Friendship Horticultural Major Maintenance Plan 2012–2015.

- Rinaldi, Bianca Maria (2011). The Chinese Garden – Garden Types for Contemporary Landscape Architecture.

- Rose, Lorna & Colliton, Gary (1988). The Garden of Friendship.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Sydney City Council (2019). Cartographica – Sydney on the Map.

- Sydney Harbour Foreshore Authority: Planning & Infrastructure (2012). The Chinese Garden of Friendship – Horticulture Major Maintenance Plan 2012–2015.

Attribution

![]() This Wikipedia article was originally based on Chinese Garden of Friendship, entry number 2017 in the New South Wales State Heritage Register published by the State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) 2019 under CC-BY 4.0 licence, accessed on 26 December 2019.

This Wikipedia article was originally based on Chinese Garden of Friendship, entry number 2017 in the New South Wales State Heritage Register published by the State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) 2019 under CC-BY 4.0 licence, accessed on 26 December 2019.

External links

- Official website

- McCormack, Terri (2008). "Chinese Garden of Friendship". Dictionary of Sydney. Retrieved 26 September 2015. [CC-By-SA]