The Symphony in D minor is the best-known orchestral work and the only mature symphony written by the 19th-century composer César Franck. It employs a cyclic form, with important themes recurring in all three movements.

After two years of work, Franck completed the symphony on August 22, 1888. It was premiered at the Paris Conservatory on 17 February 1889 under the direction of Jules Garcin. Franck dedicated it to his pupil Henri Duparc. Despite mixed reviews at the time, it has subsequently entered the international orchestral repertoire. Although today programmed less frequently in concerts than in the first half of the 20th century, it has been recorded numerous times (more than 70 recordings are available).

Background

Franck, born in 1822 in what is now Belgium, became a naturalised French citizen in 1871.[1] That year, he was a founding member of the Société nationale de musique, established in the wake of the Franco-Prussian War by Camille Saint-Saëns and Romain Bussine to promote French music.[2] When the Société split in November 1886 over the admission of performances of works by non-French composers, Franck became its new head and, along with his former student Vincent d'Indy, was a keen proponent of programming foreign composers.[3][4]

Franck's works after 1870 reflect his growing awareness of and interest in German music, especially that of Richard Wagner. Urged on principally by his student Henri Duparc, Franck "made an effort to study one of the Wagner scores every summer during the last period of his life.".[5] Although he remained ambivalent about Wagner's compositional approach, his estimation of Wagner's merits remained, unlike others in the Société nationale (notably Saint-Saens) "in no way influenced by the nationalist dimension."[5] As a result, Franck incorporated musical elements associated with Wagnerian or Germanic stylistic approaches into his later compositions. It has been suggested that "the quality of [Franck's] imagination, his resolution of formal problems, and the extreme chromaticism of his harmony are decidedly Germanic".[6] He remained an admirer of German music and was less troubled than some of his colleagues about the so-called "L'invasion germanique" of music in France in the 1870s.[2] Indeed, Franck dedicated the symphony "to my friend Henri Duparc," the student who had principally urged him to deepen his knowledge of Wagner's operas.[2][5][7]

Franck reached his creative peak in the 1870s, when he was in his late fifties. His Piano Quintet and the oratorio Les Béatitudes appeared in 1879, the Symphonic Variations in 1885 and the Violin Sonata in 1886.[8] In 1887 he began sketches for a symphony – a musical form more associated with German than with French music.[1] Saint-Saëns's "Organ" Symphony had been well received the previous year, but only one earlier symphony by a French composer had firmly established itself in the international orchestral repertoire: Berlioz's Symphonie fantastique composed in 1830.[9] Like Berlioz,[10] Franck revered Beethoven, and several commentators[n 1] have noted the influence of Beethoven, particularly the late string quartets, on the symphony, both as to form – Franck adopted a cyclic structure – and content.[9][12][11] Like Berlioz, Franck departed from the customary four-movement form of the classical symphony of Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven; unlike the Symphony fantastique by Berlioz, which is written in five movements, Franck´s symphony is written in three.[9]

Premiere and reception

Paris's symphony orchestras had a reputation for conservatism and avoiding modern works, but the Société des concerts of the Paris Conservatoire was an exception, giving performances of new works including Saint-Saëns's "Organ" Symphony (1888).[13] Franck's symphony was first performed on 17 February 1889 in the concert hall of the Conservatoire by the orchestra of the Société conducted by Jules Garcin.[13]

The piece divided opinion. Le Figaro commented, "The new work of M. César Franck is a very important composition and developed with the resources of the powerful art of the learned musician; but it is so dense and tight that we cannot grasp all its aspects and feel its effect at a first hearing, despite the analytical and thematic note that had been distributed to the audience". The paper contrasted the "exuberant enthusiasm" of some listeners with the coolness of the reception from others.[13] There were some hostile comments. Gounod was reported as calling the work "the affirmation of impotence taken to the point of dogma".[14] [n 2] Exception was taken in conservative quarters to Franck's orchestration: Vincent d'Indy said that an unnamed colleague of Franck's on the faculty of the Conservatoire asked, "Who ever heard of a cor anglais in a symphony? Just name a single symphony by Haydn or Beethoven introducing the cor anglais".[15][n 3] Franck's use of the brass was criticised as being too blatant, with cornets added to the usual orchestral trumpets.[17]

The noted music critic, Camille Bellaigue in an 1889 review published in Revue des Deux Mondes dismissed it as "arid and drab music, without ... grace or charm," and derided the principal four-bar theme upon which the symphony expands throughout as "hardly above the level of those given to Conservatoire students."[18]

At a later hearing of the work, Le Ménestrel balanced criticism and praise: it found the music gloomy and pompous, with little to say, but saying it "with the conviction of the Pope pronouncing on dogma".[19] Nonetheless, Le Ménestrel judged the work a considerable achievement, worthy of a musician with noble tendencies, though one who had made the excusable mistake of "aspiring to a pedestal a little too high for him".[19]

Outside of the nationalist environment of French music criticism of the late nineteenth century, Franck's symphony quickly became popular. Concert programs reveal that this symphony became one of the most frequently performed French symphonies and rivalled the popularity of Beethoven's works.[3] Within several years of its composition, the symphony was regularly being programmed across Europe and in the United States. It received its American premiere in Boston on 16 January 1899 under the baton of Wilhelm Gericke.[20]

From the 1920s to around the 1970s, the symphony was popular with audiences and was frequently performed by leading U.S. orchestras, but since then it has substantially declined in prominence and is no longer part of the orchestral canon. In 2022, musicians attributed this to changing musical tastes, an overfamiliarity with the music, or the spirituality of the processional slow movement becoming less relevant in a more secular age.[21]

Analysis

Instrumentation

The score calls for two flutes, two oboes, cor anglais, two clarinets, bass clarinet, two bassoons, four horns, two cornets, two trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani, harp and strings.[22]

Form

In a departure from typical late-romantic symphonic structure, the Symphony in D minor is in three movements, each of which makes reference to the initial four-bar theme introduced at the beginning of the piece.

- Lento; Allegro ma non troppo.

- An expansion of a standard sonata-allegro form, the symphony begins with a harmonically lithe subject (below) that is spun through widely different keys throughout the movement.

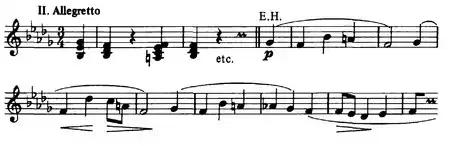

- Allegretto

- Famous for the haunting melody played by the cor anglais above plucked harp and strings. The movement is punctuated by two trios and a lively section that is reminiscent of a scherzo.

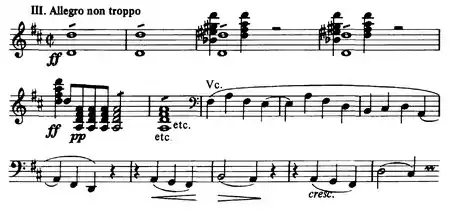

- Finale: Allegro non troppo

- The movement begins with a joyful and upbeat melody and is written in a variant of Sonata form. The coda, which recapitulates the core thematic material of the symphony, is an exultant exclamation of the first theme, inverting its initial lugubrious appearance and bringing the symphony back to its beginnings.

Recordings

The work has been frequently recorded. The BBC published a list of recordings in connection with its programme Record Review, on which a comparative review of recordings was broadcast in 2017:[23]

Notes, references and sources

Notes

- ↑ Donald Tovey cited the String Quartet No. 13;[9] Daniel Gregory Mason No. 16;[11] and in a study in The Musical Times, F. H. Shera mentioned both.[12]

- ↑ "Cette symphonie, c'est l'affirmation de l'impuissance poussée jusqu'au dogme"[14]

- ↑ Laurence Davies points out in his biography of Franck that in fact Haydn had used the cor anglais in one of his symphonies: No. 22 in E♭ major, The Philosopher.[16]

References

- 1 2 Trevitt, John, and Joël-Marie Fauquet. "Franck, César(-Auguste-Jean-Guillaume-Hubert)", Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press, 2001. Retrieved 30 June 2021 (subscription required)

- 1 2 3 Strasser, Michael. "The Société Nationale and Its Adversaries: The Musical Politics of L'Invasion Germanique in the 1870s", 19th-Century Music, vol. 24, no. 3, 2001, pp. 225–251 (subscription required)

- 1 2 Deruchie, Andrew (2013). The French symphony at the fin de siècle : style, culture, and the symphonic tradition. Rochester, NY. ISBN 978-1-58046-838-1. OCLC 859154652.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ "Société nationale de musique", Bibliotheque nationale de France. Retrieved 13 May 2021

- 1 2 3 Fauquet, Joël-Marie (2004). "César Franck als Vokalkomponist". In Jost, Peter (ed.). César Franck: Werk und Rezeption (in German). Stuttgart: Steiner Verlag. p. 17. ISBN 9783515082655. OCLC 470365126.

Die Wagner Frage weist im Hinblick auf Franck besondere Bedeutung auf. Vor 1870 kannte Franck Wagner nur sehr oberflächlich. Folglich lässt sich als einzige Einfluss Wagners auf Francks Musikstil lediglich die zunehmende Chromatik in Anschlag bringen. Eingeschränkt wird dies zudem dadurch, dass Chromatik bereits in einigen Werken France aus dem 1840er Jahren, unter dem Einfluss Liszts, anzutreffen ist. Nach 1870 wurde Frank von seinen Schülern, in erster Linie von Henri Duparc, zur Musik Wagners gedränkt. Frank urteilte freilich über die Walküre negativ, und die Begeisterung, die er nach der Überlieferung von Bréville für den ersten Akt von Tristan und Isolde äußerte, den er in den Concerts Lamoureux 1884 hörte, steht im Widerspruch zum Missfallen, zu dem in die Lektüre der Partitur veranlasste. Dennoch bemühte sich Franck unter dem Druck seine Schüler in seiner letzten Lebenszeit, jeden Sommer eine der Wagner Partituren zu studieren. Aber er ärgerte sich, wenn diese sich auf Wagner beriefen, um eine anderen kompositorische Lösung zu finden als die, die er ihnen vorschlug. In der Tat, empfand wohl Franck wie andere französische Musiker für Wagner Bewunderung wie Abscheu, mit dem einen unterschied, dass für ihn der nationalistische Aspekt nicht in Betracht kam.

- ↑ Sackville-West and Shawe-Taylor, p. 285

- ↑ Franck, title page

- ↑ Bayliss, p. 205

- 1 2 3 4 Bayliss, p. 203

- ↑ Bonds, p. 409

- 1 2 Mason, p. 71

- 1 2 Shera, F. H. "César Franck's Symphony in D Minor". The Musical Times, April 1936, pp. 314–317 (subscription required)

- 1 2 3 Darcours, Charles. "Notes de musique", Le Figaro, 20 February 1889, p. 6

- 1 2 Kunel, p. 190 and Stove, p. 266

- ↑ D'Indy, p. 62; and Davies, p. 236

- ↑ Davies, p. 236

- ↑ Mason, p. 69

- ↑

Bellaigue, Camille (15 March 1889). "Revue Musicale". Revue des Deux Mondes. 92 (2). 460. JSTOR 44777533.

Oh! l'aride et grise musique, dépourvue de grâce, de charme et de sourire! Les motifs eux-mêmes manquent le plus souvent d'intérêt : le premier, sorte de point d'interrogation musical, n'est guère au-dessus de ces thèmes qu'on fait développer par les élèves du Conservatoire.

- 1 2 Boutarel, Amédée "Concert Lamoureux", Le Ménestrel: journal de musique, 26 November 1893, p. 383

- ↑ Burk, John N. (1945). "Wilhelm Gericke: A Centennial Retrospect". The Musical Quarterly. 31 (2): 163–187. doi:10.1093/mq/XXXI.2.163. JSTOR 739507.

- ↑ Allen, David (2022-03-18). "What Happened to One of Classical Music's Most Popular Pieces?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2022-03-19.

- ↑ Franck, p. 1

- ↑ "Record Review", BBC. Retrieved 1 July 2021

Sources

Books

- Bayliss, Stanley (1949). "César Franck". In Ralph Hill (ed.). The Symphony. Harmondsworth: Penguin. OCLC 1023580432.

- Davies, Laurence (1977). César Franck and his Circle. New York: Da Capo. OCLC 311525906.

- D'Indy, Vincent (1909). César Franck. London: John Lane. OCLC 13598593.

- Franck, César (1890). Symphony in D minor (PDF). Paris: Hamelle. OCLC 1156443684.

- Kunel, Maurice (1947). La Vie de César Franck. Paris: Grasset. OCLC 751302461.

- Mason, Daniel Gregory (1920). The Appreciation of Music, Vol. III: Short Studies of Great Masterpieces =. New York: H.W. Gray. OCLC 670027725.;

- Sackville-West, Edward; Desmond Shawe-Taylor (1955). The Record Guide. London: Collins. OCLC 500373060.

- Stove, R. J. (2012). César Franck: His Life and Times. Lanham: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-81-088208-9.

Journals

- Bonds, Mark Evan (Autumn 1992). "Sinfonia anti-eroica: Berlioz's Harold en Italie and the Anxiety of Beethoven's Influence". The Journal of Musicology. 10 (4): 417–463. doi:10.2307/763644. JSTOR 763644. (subscription required)

See also

External links

- Symphony in D minor: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project