| Theban tomb TT8 | |

|---|---|

| Burial site of Kha and Merit | |

The burial chamber of Kha and Merit as discovered in 1906 | |

TT8 | |

| Coordinates | 25°43′44″N 32°36′03″E / 25.7289°N 32.6009°E |

| Location | Deir el-Medina, Theban Necropolis |

| Discovered | Before 1824 (chapel) 15 February 1906 (tomb) |

| Excavated by | Ernesto Schiaparelli (1906) Bernard Bruyère (1924) |

| Decoration | Offering and feasting scenes (chapel) Undecorated (tomb) |

The tomb of Kha and Merit, also known by its tomb number TT8, is the funerary chapel and tomb of the ancient Egyptian foreman Kha and his wife Merit, in Deir el-Medina. Active during the mid-Eighteenth Dynasty, Kha supervised the workforce who constructed royal tombs in the reigns of pharaohs Amenhotep II, Thutmose IV and Amenhotep III (r. 1425 – 1353 BC). Of unknown background, he rose to this position through skill and was rewarded by at least one king. He and his wife Merit had three known children. Kha died in his 50s or 60s, while Merit died before him, seemingly unexpectedly, in her 30s.

The couple's pyramid-chapel was known since at least 1824 when one of their funerary stele entered the collection of the Museo Egizio in Turin, Italy. Scenes from the chapel were first copied in the 19th century by early Egyptologists including John Gardiner Wilkinson and Karl Lepsius. The paintings show Kha and Merit receiving offerings from their children and appearing before Osiris, god of the dead. The texts of the chapel were defaced during the reign of Akhenaten and later restored, indicating it was one of the oldest chapels in the cemetery.

Kha and Merit's undisturbed tomb was discovered in February 1906 in excavations led by the Egyptologist Ernesto Schiaparelli on behalf of the Italian Archaeological Mission, dug into the base of the cliffs opposite the chapel. This separation contributed to its survival, allowing the entrance to be quickly buried by debris. The burial chamber contained over 400 items including carefully arranged stools and beds, neatly stacked storage chests of personal belongings, clothing and tools, tables piled with foods such as bread, meats and fruit, and the couple's two large wooden sarcophagi housing their coffined mummies. Merit's body was fitted with a funerary mask; Kha was provided with one of the earliest known copies of Book of the Dead. Their mummies were never unwrapped. The use of X-rays, CT scanning and chemical analysis has revealed neither were embalmed in the typical fashion but are well preserved. Both wear metal jewellery beneath their bandages, although only Kha has funerary amulets.

Almost the entire contents of the tomb was awarded to the excavators and was shipped to Italy soon after the discovery. It has been on display in the Museo Egizio in Turin since its arrival and has been redisplayed several times, most recently in 2015, where an entire gallery is dedicated to the exhibition of TT8.

Kha and Merit

| Kha and Merit in hieroglyphs | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Era: New Kingdom (1550–1069 BC) | ||||||||

Kha (also rendered KhaꜤ[1] or Khai[2]) was a foreman for the village of Deir el-Medina during the mid-Eighteenth Dynasty.[3] Often referred to as an architect in modern publications, he supervised the workmen responsible for cutting and decorating royal tombs in the Valley of the Kings (known as "the Great Place"[4]) in the reigns of Amenhotep II, Thutmose IV, and Amenhotep III (r. 1425 – 1353 BC).[5][6] His origins are unknown. His only attested parent is his father, Iuy, who bears no titles and about whom nothing is known.[7][8] Given his lack of hereditary titles, Kha is assumed to have attained his position through skill.[5] The Egyptologist Barbara Russo suggests that his mentor or tutor was a man named Neferhebef, who has similar titles to Kha and whose name appears on items in Kha's tomb. Additionally, he is depicted alongside his wife Taiunes in Kha's funerary chapel.[9] Evidently the two had a close relationship, sometimes suggested to be that of father and son,[10] although there is no evidence they were related.[7]

Kha likely began his career in the reign of Amenhotep II.[11] Ernesto Schiaparelli considered him to have been active in the reign of the preceding king, Thutmose III, based on the presence of seals bearing his name within the tomb[12] but this probably reflects the use of this king's name long after his reign.[13] Kha is generally thought to have been responsible for the design and cutting of the tombs of Amenhotep II, Thutmose IV, and Amenhotep III.[11] Russo proposes that Kha began his career under the supervision of Neferhebef, who oversaw the construction of the tomb of Amenhotep II.[14] He attained the role of "chief of the Great Place" (ḥry m st Ꜥꜣ(t)) during the reign of Thutmose IV and reached the peak of his career during the reign of Amenhotep III, when he was given the title of "overseer of (construction) works in the Great Place" (imy-r kꜣ(w)t m st Ꜥꜣ(t)).[15] Russo suggests Kha entered the bureaucracy at the end of his career, based on his titles of "overseer of the works of the central administration" (imy-r kꜣ(w)t pr-Ꜥꜣ) and "royal scribe" (sš nswt).[15] His position as "royal scribe" is debated as it only appears on two staves. Eleni Vassilika suggests "royal scribe" was an early position he held,[16] while Russo considers it was late in his career based on the style and intricacy of the staffs the title appears on.[17] Dimitri Laboury doubts the title referred to Kha at all, pointing to the many grammatical errors in texts in both the chapel and tomb, and posits the sticks were gifts from a colleague who bore the title.[18]

Kha enjoyed a successful career and received several royal gifts for his service. The first was a gilded cubit rod, given by Amenhotep II, and he later obtained a bronze pan from Amenhotep III. His most significant award was a "gold of honour", although which ruler it was given by is debated. Thutmose IV or Amenhotep III are considered the most likely candidates based on the style of the jewellery.[19][20] His mummy wears some of the jewellery he obtained, such as signet rings and a collar made of gold disc beads around his neck beneath his mummy wrappings.[21][22] Preparations for his tomb likely began in the reign of Thutmose IV, as his name occurs most frequently as a seal on vessels.[13] Based on the style of his coffins and the juvenilising art style seen on the painted funerary chests, Kha died in the reign of Amenhotep III, likely in his third decade of rule.[5][23] The period of his death can be further narrowed down to the last few years of Amenhotep's reign if, as Russo suggests, he is identical to the "royal scribe Kha" attested on jars from the palace complex of Malkata dating to the Sed (jubilee) festival in year 35.[24]

Merit (also transcribed as Meryt[1]) was Kha's wife. She is titled "lady of the house" (nbt pr), a common title given to married women.[25][26] She likely died before Kha and unexpectedly as she is buried in a coffin intended for her husband. They had three known children: two sons named Amenemopet and Nakhteftaneb, and a daughter also named Merit (Merit II).[5] A third son named Userhat is sometimes attributed to them but his father is identified as Sau, a scribe of grain-keeping. Amenemopet also worked in Deir el-Medina and is titled "servant in the royal necropolis".[27] No title is given for Nakhteftaneb;[27] he seems to have been in charge of the funerary cult of his parents.[28] Merit II became a singer of Amun. All the children outlived their mother[5] but Amenemopet may have died before his father.[28]

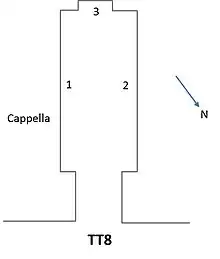

Chapel

Location and description

The funerary chapel of Kha and Merit is located at the northern end of the Deir el-Medina necropolis.[29][Note 1] Constructed of mudbrick, it takes the form of a small, slightly rectangular pyramid. The sides measure approximately 4.70 metres (15.4 ft) square and have an incline of 75 degrees, giving the structure a projected total height of 9.32 metres (30.6 ft); the exterior was plastered and whitewashed.[33][34] It is one of few surviving Eighteenth Dynasty chapels from Deir el-Medina and is an early example of the pyramid form,[35] derived from the tombs of contemporary nobility.[36][37] This shape became typical for chapels in the workmen's village in later dynasties.[35][36] The chapel was in a ruined state by the time of European interest in it, during 19th and 20th centuries;[38] the exterior was partially restored by the Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale (IFAO).[39] As of 2008, it is not open to tourists.[38]

The chapel was topped by a pyramidion of whitewashed sandstone decorated on all sides with sunk bas-reliefs of Kha worshipping the sun god Ra and inscribed with hymns to him at the stages of his journey: the east and damaged north faces adore Ra at sunrise, the south face praises him as he crosses the sky, and the west face worships Ra as he sets. The pyramidion was reused for a small, anonymous pyramid-chapel near the courtyard of TT290, a few metres south-east of TT8 and was rediscovered by Bernard Bruyère on 8 February 1923.[39][40] It is now housed in the Louvre in Paris, France.[41]

The chapel faces the northeast and is entered through a single doorway with large doorposts. Nothing remains of the lintel and cornice they supported. Like other pyramid-chapels in the necropolis, there was probably a niche cut into the face of the pyramid, above the door, into which a small stele was set. The interior of the chapel is a single room measuring 3 by 1.6 metres (9.8 ft × 5.2 ft) with a vaulted ceiling 2.15 metres (7.1 ft) high; a small relieving chamber was probably present above. A niche in the back wall housed the stele now in the Museo Egizio, Turin, Italy. This wall is badly damaged, probably as a result of the removal of the stele.[42]

The chapel sits at the back of a walled rectangular courtyard which is set back into the rocky hillside.[33][43] It was likely entered through a gateway in the shape of a small pylon.[37] Unusually, the tomb is not directly associated with the chapel itself, instead being cut into the base of the cliffs opposite.[41] In 1924, Bernard Bruyère excavated the courtyard to see if the presence of a burial shaft close to the area was the reason for the separation. On the right side of the courtyard, 3 metres (9.8 ft) from the entrance of the chapel, in the expected location of a shaft, he found a pit 0.75 metres (2.5 ft) deep and 1 metre (3.3 ft) wide lined with mudbrick. Schiaparelli suggested that this pit was where Kha's additional copy of the Book of the Dead and other funerary items, known before the discovery of the tomb, were originally deposited. Bruyère suggests the separation of chapel and tomb is instead due to the very poor quality of the rock beneath the chapel and courtyard.[44]

The chapel during Schiaparelli's 1906 excavations

The chapel during Schiaparelli's 1906 excavations The interior of Kha and Merit's funerary chapel in 1906

The interior of Kha and Merit's funerary chapel in 1906.jpg.webp) Pyramidion of Kha's chapel, now in the Louvre

Pyramidion of Kha's chapel, now in the Louvre

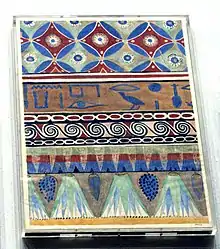

Decoration

The interior of the chapel was plastered and fully decorated but has been badly damaged over the millennia. On stylistic grounds, it was completed in the reigns of either Thutmose IV or Amenhotep III.[45] As with the exterior, the decorative scheme mimics the types of scenes and layouts seen in the chapels of the elite. Kha likely employed his own skilled workmen to execute the decoration. Unlike the tombs of nobles, the texts have errors such as unconventional hieroglyph groupings and omitted signs indicating the artists had "limited hieroglyphic literacy".[46]

The brightly coloured paintings have drawn attention, being copied by several Egyptologists in the 19th century including John Gardiner Wilkinson and Karl Lepsius.[41] Ernesto Schiaparelli briefly described the chapel in his 1927 publication of the burial chamber; a full study of the decoration was made in the 1930s by Jeanne Marie Thérèse Vandier d'Abbadie during the IFAO's excavations of the village.[47]

The ceiling is covered with two different geometric and floral patterns separated by a central inscription. The vault is bordered on each side by another band of text and an upper frieze of alternating lotus flowers, buds, and grapes separates the inscriptions from the wall scenes proper.[42]

The back wall, now badly damaged, is divided into three registers around the central stele niche. A pair of Anubis-jackals face each other across a large bouquet in the uppermost, semi-circular register.[48] Unlike the rest of the decoration, this is executed on a light grey ground.[49] In the second register, two men, one on the left and one on the right, kneel and offer bouquets. The left side of the lowest register shows a seated man and woman, who are identified as Neferhebef and Taiunes, with offerings before them and receive ministrations from a man, on the right side of the register, dressed as a sem-priest. He may be their son but his identity is unknown as the inscription is badly damaged.[1][49]

On the left wall Kha and Merit are depicted seated before an offering table in a banquet scene. Their daughter, also named Merit, bends to adjust her father's collar and one of their sons presents them with offerings. Below this scene, a narrow register depicts an additional offering of four amphorae, garlanded with flowers and fruit attended by a servant. The rest of the wall depicts guests and musicians. In a lower register, offering bearers advance in the opposite direction, towards a seated couple who are now mostly obliterated by damage.[50][51]

The right wall has the same layout as the left. The large scene depicts the god Osiris seated in a raised kiosk; he receives offerings from Kha and Merit, who are accompanied by their children. In the two smaller registers, servants approach with offerings of a goat or gazelle and a white ox wearing a floral garland.[52][53][54]

The decoration has received damage over the millennia since its execution. The first damage occurred only a decade or so after the chapel went into use. The name of the god Amun was erased wherever it occurred during the reign of Akhenaten. It was later restored but in a way that does not match the original text. Later, all the faces of the figures were hammered out, possibly by Copts.[55] The decoration near to the door deteriorated further after the partial collapse of the ceiling in this area.[53] The chapel was also targeted by robbers. The back wall was damaged in the 19th century during the removal of the stele, and a hieratic graffito, mentioned by Lepsius in the 1840s, was destroyed sometime after his publication.[1][56]

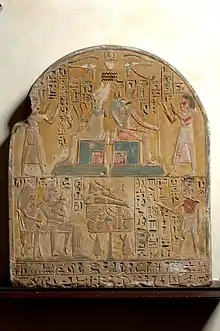

Steles

A painted stone stele dedicated to Kha and Merit once stood in the niche in the back wall of the chapel. In 1824 it was donated to the Museo Egizio as part of the collection of Bernardino Drovetti,[57] having been removed from the chapel and purchased by his agents around 1818.[58] The first register depicts Kha adoring Osiris and Anubis, who sit back to back. In the second register, Kha and Merit, accompanied by a young child, sit before a table of offerings; their son Amenemopet stands on the far side, officiating. The two lines of text at the bottom of the stele gives offerings to the gods Amun, Ra, Ra-Horakhty, and Osiris, and asks for funerary offerings to be given.[53]

A second stele is housed in the British Museum. The large upper register depicts Thutmose IV offering floral bouquets and incense to an enthroned Amun and the deified Ahmose-Nefertari, who stands behind him; Kha kneels in adoration below them in the second register. This stele was likely originally made for the Kha of TT8 and was later restored and adapted by another Deir el-Medina foreman, Inherkau (whose name can be abbreviated to Kha), owner of TT299. The image of Amun, hacked out during the Amarna Period, was restored, and the name and titles of Inherkau's wife Henutdjuu were added in ink instead of being cut into the stone.[59]

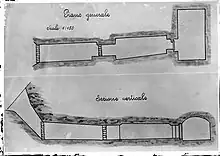

Tomb

Given his role in the construction of royal tombs, Kha probably participated in the construction of his own tomb (and chapel) along with his sons or workmen.[60] Atypically for non-royal tombs, the burial chamber was not associated with the chapel but dug into the cliffs nearby. This separation contributed to the tomb escaping the attention of robbers,[61] as did its position at the base of the cliffs, which allowed the entrance to be covered by debris from later tombs cut above.[3]

Discovery and investigation

The tomb was discovered on 15 February 1906 during excavations conducted by the Italian Archaeological Mission headed by the Egyptologist Ernesto Schiaparelli.[3] The Mission began investigating the village of Deir el-Medina in 1905 and their 1906 excavation season focused on the village necropolis.[62] The partially ruined chapel of Kha and Merit was what drew Schiaparelli's attention to this area. Unlike most of the ruined chapels on the hillsides, this was known to date to the Eighteenth Dynasty, based on the content of the scenes, and the erasure then restoration of the name of Amun.[61][32] He noted that the rubble below the opened and looted Twentieth Dynasty tombs in the cliffs to the north of the chapel was unlikely to be the product of the construction of these tombs alone. The excavator reasoned that "presumably other older tombs had been dug at the bottom of the mountain but were not visible because of being hidden by the debris".[63] Excavation began at the mouth of the valley and proceeded towards the end. More than 250 workers, divided into several gangs, excavated for four weeks, uncovering only opened and robbed tombs; the discoloured limestone fill was mixed with bone, pottery, and cloth. In February 1906, after clearing two thirds of the valley, and 25 metres (82 ft) north of Kha and Merit's chapel, an area of clean, white limestone chip was encountered.[63][57] A further two days of digging uncovered an irregular opening with a set of stairs that "descended steeply into the bowels of the mountain".[63] An intact blocking wall constructed of stones cemented with mud plaster was encountered at the bottom of the stairs. Wanting to make sure that the tomb was as intact as it appeared, a hole was made and the reis (foreman) Khalifa wriggled through it "and an immediate exclamation of joy on his part assured us that our hopes would not be dashed".[63] Evening was falling so work was suspended for the day; that night the tomb was guarded by the supervisor Benvenuto Savina and Alessandro Casati.[63]

The following morning,[64] with the Inspector of Antiquities of Upper Egypt, Arthur Weigall, in attendance, the first wall was demolished, revealing a horizontal corridor. Less than 10 metres (33 ft) ahead was another intact blocking wall which opened into a taller, carefully cut passage. This corridor contained overflow from the burial chamber, these items included Kha's bed with bundles of persea branches underneath, a large lamp stand, baskets, jars, baskets of fruit, a wooden stool, and a whip with Kha's name written on it.[63][65] The passage was sealed by a wooden door which "looked for all the world as though it had been set up yesterday"[66] and locked with a wooden lock; the spring for the bolt was carefully sealed with clay.[66] A thin saw was inserted between the two planks of wood and used to cut the crossbars on the back of the door, allowing entry into the burial chamber and preserving the lock.[63]

Weigall was the first to enter the room, followed by Schiaparelli and members of his team including Francesco Ballerini, Casati, Savina, and the dragoman Ghattas.[63] The newly revealed burial chamber was rectangular, measuring 5.6 by 3.4 metres (18 ft × 11 ft) with a 2.9 metres (9.5 ft) high barrel vaulted ceiling.[54] The walls were smoothed, plastered, and painted yellow but otherwise undecorated. The contents, which "looked new and undecayed"[67] were carefully placed "in perfect order in the chamber, just as the relatives of the deceased had arranged it before leaving the tomb".[63] Kha and Merit's black wooden sarcophagi were placed against the back and right walls respectively, both were covered with linen palls still "soft and strong like the sheets of our beds".[67] Against the left wall was Merit's bed, "made up with sheets, blankets, and two headrests".[63] At its foot was her toilet box, and near it was her large wig box. Opposite, garlanded and standing on a chair, was a wooden statue of Kha. The rest of the space was filled with stools piled with linen, tables laden with bread, sycamore and persea branches, pottery, alabaster, and bronze jars on stands and tables, stacked boxes, nets of doum palm fruit, and another lamp stand, similar to the one found outside the room.[63]

The tomb and its contents were recorded, photographed, and cleared in only three days, likely due to fear of theft. A single plan drawing was made which noted the locations of eighteen key objects, and few photos of the interior were taken. On 18 February 1906 the contents were transferred to the tomb of Amun-her-khepeshef (QV55) in the Valley of the Queens before being shipped to Cairo and ultimately to Italy.[37][68]

Schiaparelli published the discovery over 20 years later, in 1927, a year before his death. The large volume makes some omissions and mistakes in recalling the specifics of the discovery, such as neglecting to mention the date of the discovery,[69] stating that many of Kha's possessions were in a box too small for them, and saying that Merit's toilet box was unsealed.[70] The publication used a blank floor plan and only three photos of the burial chamber, leading to confusion regarding the positioning of objects not included in the unpublished plan or seen in photographs.[71]

Contents

Discovered entirely intact and containing over 440 items, TT8 is considered the "most abundant and complete non-royal burial assemblage ever found in Egypt".[3] The majority of the objects were used by Kha and Merit in life, such as clothing and furniture. Clothing was laundered and neatly folded in baskets or chests, and some furniture was given a fresh coat of paint. Other pieces were made to be placed in the tomb, having painted decoration in imitation of expensive inlay work and hieroglyphic texts that are often full of grammatical errors. The various boxes and chests were labelled for the use of either Kha or Merit with brief inscriptions in ink.[72] Different kinds of breads, meats, vegetables, fruits and wine were also provided for the deceased to eat in the afterlife. Despite the large number of items within the tomb, they were carefully laid out in an orderly way that "suggested a tidying-up done that very morning".[73] The quality and quantity of objects is assumed to be typical of an upper-middle class burial.[22] Although less richly outfitted than noble or royal burials, it provides a more complete picture of the variety of food, clothing, and personal objects expected in burials during the mid-Eighteenth Dynasty.[22] Since 2017, the tomb's contents have been the subject of the "TT8 Project", a multidisciplinary and non-invasive study of all the objects, the full publication of which is planned for 2024.[3]

Personal possessions

The personal items belonging to the couple were found neatly stored in various boxes, chests, and baskets.[74] Kha's personal possessions make up the bulk of the objects, with some 196 items inscribed for him.[75] These included work tools such as a rare folding wooden cubit rod (in its own leather pouch),[76] scribal palettes, a drill, chisel, an adze, and a possible level. Among his cosmetics were bronze razors in a leather bag, a comb, and tubes of kohl. Also present were items for preparing and serving drinks, including a funnel, two metal strainers, a silver jar, and faience bowls.[74] His clothing, marked with his monogram, was stored in several boxes and a bag. All were made of linen and consisted of 59 loincloths and 19 tunics, and further rectangular pieces of fabric, identified by Schiaparelli as four shawls and 26 sashes or kilts; seven of these were knotted together with loincloths to form sets of clothing.[77][74] Other objects belonging to Kha were distributed around the tomb, such as four sticks (two with decorative bark inlay), and a traveling mat, folded on a net of doum palm nuts.[74]

Several items within the tomb were gifts to Kha from others. A cubit rod covered entirely in gold leaf and bearing the cartouches of Amenhotep II was likely an award from that king, although Kha's name does not appear on it.[78] Another royal gift was a large dish with the throne name of Amenhotep III inscribed on the handle. It was likely produced in the royal workshops and presumably given to Kha as part of a royal award.[79] A large metal situla bears the name and titles of Userhat, a priest of the funerary cults of Mutnofret, wife of Thutmose I, and Sitamun, daughter of Ahmose I. He likely worked in the west of Thebes, presumably the Deir el-Medina area, and the gift was in recognition of Kha's high status at the height of his career.[80] One of Kha's two scribal palettes dates to the reign of Thutmose IV and belonged to a high official named Amenmes, who was buried in TT118.[81] Among his titles was "overseer of all of the construction works of the king", meaning he oversaw all of the royal construction projects and in this role likely worked directly with Kha.[82] One stick was a gift from Neferhebef, with a dedicatory inscription recording that it was made by him, presumably for Kha, but the space where Kha's name would be inserted was left blank.[83] Another stick belonged to Khaemwaset, who likely worked alongside him as he also bears the title "chief of the Great Place". Kha's senet board had previously belonged to a man named Benermeret who was associated with the cult of Amun at Karnak temple, and who had it inscribed and decorated for his parents Neferhebef and Taiunes.[84]

Merit's personal possessions were much fewer than Kha's, and were placed beside her bed, near the door.[85] Egyptologist Lynn Meskell considers this difference in the quantity of items to be a reflection of the inequality between the sexes at the elite level of ancient Egyptian society.[86] A large wooden cabinet, 1.10 metres (3.6 ft) tall, contained her wig which "still shines with the perfumed oils that were applied to it".[85] It is one of the best examples to have survived from ancient Egypt and represents the "enveloping" style of wig that was common during the Eighteenth and early Nineteenth Dynasties. It is made of locks of human hair styled into tight waves and ending in tiny ringlets. At the back, the wig forms three thick plaits. It would not have been thick enough to entirely cover Merit's own hair when worn and would have been an addition to her own styled hair. Investigation using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry indicated the presence of plant oils and "balsam". As no fixative is present on the wig, it is suggested it was styled by braiding when wet, and that the oils mentioned by Schiaparelli are a "perfumed moisturizing treatment meant to keep the hair in good condition".[87][88] Two smaller baskets contained personal effects such as needles, a razor, bone hairpins, combs, spare braids of hair, a tool possibly used to curl hair or wigs, and dried raisins. A large sheet, stained with oil but carefully stored, was considered by Schiaparelli to be Merit's dressing gown.[89][90] Merit's cosmetics were stored inside a box likely made especially for the funeral, with funerary inscriptions and painted in imitation of inlay. They consisted of a wooden comb and vessels of alabaster and faience holding ointments and oils; two objects were of multi-coloured glass – a small jar for oils and a kohl tube.[89][91]

Kha's folding cubit rod with leather case

Kha's folding cubit rod with leather case Kha's senet board, originally made for Neferhebef

Kha's senet board, originally made for Neferhebef Merit's wig, styled by being plaited while wet and unplaited when dry, to give a crimped effect[87]

Merit's wig, styled by being plaited while wet and unplaited when dry, to give a crimped effect[87]

Furniture and furnishings

The tomb contained many items of everyday furniture including stools, footrests, tables, and beds, sourced from the couple's house in Deir el-Medina.[Note 2] The most obvious funerary piece was a single high-backed chair, on which was placed a statuette of Kha. Like the other pieces, it has a funerary inscription but uses paint instead of costly inlay, and lacks wear on the strung seat. Fourteen stools of various forms were placed in the tomb; these were all items used by Kha and Merit in life. The most unusual example is a folding stool with a leather seat and legs ending in duck heads inlaid with ivory. The tables found in the tomb were simple, either of wood, or constructed of papyrus stems. A single small table had more elaborate construction, being made of wooden slats; it held Kha's senet box when found, which may have been its usual purpose. The largest pieces of furniture belonging to Kha and Merit were their beds, each with a strung cord mattress. Kha's bed was placed in the corridor outside the burial chamber due to lack of space within the room. Merit's was made up with sheets, blankets, and two headrests, one of which was entirely wrapped in fabric. Thirteen chests of varying sizes and styles made up the rest of the furniture placed within the tomb. All were of wood, plain or white-washed but five were painted in imitation of inlay and of these, three bore scenes of Kha and Merit receiving offerings from their sons.[94][95]

The two wooden lamp stands are the only examples of their kind from ancient Egypt. They are made in the shape of papyrus stalks with open umbels and approximately 1.5 metres (4.9 ft) tall. Only the example found inside the burial chamber had a bronze lamp, variously identified as having the shape of a leaf,[96] bird,[97] or bulti-fish;[98] it had been left half-full of fat with the wick burning when the tomb was closed.[99][100]

Folding stool with leather seat and legs ending in carved duck heads

Folding stool with leather seat and legs ending in carved duck heads Merit's bed, around which many of her personal belongings were found, and some of the numerous wooden stools found in the tomb

Merit's bed, around which many of her personal belongings were found, and some of the numerous wooden stools found in the tomb One of the wooden boxes with painted decoration in imitation of inlay

One of the wooden boxes with painted decoration in imitation of inlay Lampstand from the burial chamber shaped like a papyrus stalk with bronze lamp

Lampstand from the burial chamber shaped like a papyrus stalk with bronze lamp

Food and drink

The tomb was stocked with numerous foodstuffs which were piled on tables and in bowls, packed in amphorae, and stored in baskets. The most numerous category was bread of "a more varied and plentiful assortment than has been discovered in any other tomb or exists in any museum".[101] The bulk of the loaves were arranged on the low tables or packed within a large ceramic vessel. Most were of the standard round flat form but others were made into various shapes such as triangles, jars or trussed animals, or have grooves or holes that may suggest fertility. Wine was also well represented, the containers for which were labelled with their year and place of origin. Most were sealed but those that were open had evaporated over the millennia, leaving only a residue. Chunks of meat and roasted birds were stored salted in amphorae while salted fish were placed in bowls among the bread. Vegetable dishes consisted of minced and seasoned greens in bowls and jars accompanied by bundles of garlic and onions, and baskets of cumin seeds. Fruits included grapes, dates, figs, and nets of doum palm nuts.[102][103] Imported species were represented by a box of almonds (mixed with domestically-grown tiger nuts) and a basket of juniper berries.[104] Thirteen sealed alabaster vessels contained oils, seven of which Schiaparelli identified as the "seven sacred oils" used in funerary ritual. Also included was oil and salt for cooking and the fuel needed for the kitchen fire, in the form of dried cow dung.[102][103] Few of the sealed vessels were opened by Schiaparelli so the contents of sealed (and unsealed) containers have been investigated using non-invasive techniques such as X-ray fluorescence (XRF), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS), and types of mass spectrometry (MS), which has identified the presence of oils, fats, beeswax, and other organic compounds.[105][106]

Carob fruit secured to a tall stand with papyrus strips

Carob fruit secured to a tall stand with papyrus strips Various forms of bread, including one shaped like a trussed gazelle

Various forms of bread, including one shaped like a trussed gazelle An opened and broken amphora containing salted birds

An opened and broken amphora containing salted birds Sealed and unsealed painted amphorae and jugs that contained liquids

Sealed and unsealed painted amphorae and jugs that contained liquids

Sarcophagi and coffins

The largest items within the tomb were the two outer coffins (sarcophagi) containing the mummiform coffins and mummies of Kha and Merit.[107] Kha's was placed against the far wall, with Merit's positioned at a right angle to it against the long wall.[108] Both were covered by large linen sheets, the fabric covering Kha's being approximately 15 metres (49 ft) long and 2 metres (6.6 ft) wide.[109] The two sarcophagi are similar in style and construction, although they differ in size (Kha's is larger), and base (Kha's with sledge runners and Merit's without). Both are made of black-painted sycamore wood without any additional decoration.[110] Referred to as "bitumen" in Schiaparelli's publication, the black coating is made mainly of Pistacia resin and small amounts of other plant-derived products.[111] Similar sarcophagi with additional gilded or painted text and figures were found in the tombs of the contemporary nobles Yuya, his wife Thuya, and Maiherpri, but Schiaparelli remarks that sarcophagi of this type must "have been common to all high-ranking dignitaries, princes, and princesses" having found fragments of such boxes during his excavations in the Valley of the Queens.[109][112] Given their large size, they were brought into the tomb in sections and reassembled; marks made on the edges of each piece assisted in this task.[109]

Kha's sarcophagus contained a further set of two nested coffins in human shape. They are "superb examples" of the wealth and craftsmanship seen during the reign of Amenhotep III.[113] They are of identical style and workmanship to those of the nobility, if of smaller size.[114] The outer coffin has a black-based design but "the face, hands, alternate stripes of the wig, bands of inscriptions and figures of funerary gods in gilded gesso".[113] When revealed, it was covered almost entirely by Kha's copy of the Book of the Dead.[115][5] Underneath, the neck of the coffin was draped with a garland of melilot leaves, cornflowers, and lotus petals. The innermost coffin was entirely gilded.[115] The eyes and eyebrows are inlaid with quartz or rock crystal and black glass or obsidian, with blue glass for the eyebrows and cosmetic lines, all set into bronze or copper sockets. Across his chest is a broad collar with falcon-head terminals and below, his arms are crossed in the manner of Osiris, god of the dead. Below is the goddess Nut as a vulture with outstretched wings grasping two shen-signs in her talons.[116] Across the chest of this was placed a similar floral garland. The red-dyed flax ropes used to lower the inner coffin into the outer were still in place around the ankle and neck. Additionally, the inner coffin sat on a layer of natron inside the outer coffin. The lids of the coffins were closed with small wooden dowels.[115]

Merit's sarcophagus contained only a single coffin wrapped in a linen shroud. The coffin was not made for her; it is much too large for her mummy and the inscriptions only name Kha.[117] Merit's coffin combines features of Kha's outer and inner coffins, with the lid being entirely gilded and the trough having a black-based design.[118] The discrepancy in design represents a merging of the typical two-coffin set into one.[119][120] Her coffin is of lesser quality than Kha's and is less costly;[121] the sculpting of the face is rougher, the figures of deities are roughly rendered, and the text is incised instead of being modeled in plaster.[119] The difference in quality is likely due to this coffin being commissioned by Kha earlier in his career, before he could afford a more expensive two-coffin set.[122] A large figure of the goddess Nut is painted on the interior of the coffin trough.[123] Merit likely died unexpectedly, resulting in a coffin made for her husband being used for her burial.[124]

The outer anthropoid coffin of Kha

The outer anthropoid coffin of Kha Side view of the outer coffin of Kha

Side view of the outer coffin of Kha Inner coffin of Kha

Inner coffin of Kha Side view of the inner coffin of Kha

Side view of the inner coffin of Kha Merit's inner coffin, adorned with a vulture goddess on the chest, similar to her husband's

Merit's inner coffin, adorned with a vulture goddess on the chest, similar to her husband's

Mummies

The wrapped mummies of Kha and Merit were found undisturbed within their coffins. Schiaparelli decided against unwrapping them, so the pair have been investigated with non-invasive methods. They were X-rayed in 1966 and 2014,[125] and CT scanned in 2002 at the Institute of Radiology in Turin[25] and again in 2016.[126] Neither had undergone a mummification procedure typical for the Eighteenth Dynasty; their internal organs were not removed, explaining the absence of canopic jars.[127] The lack of organ removal has led to suggestions that the bodies were treated using a shorter procedure, with little care,[128] or that they were not embalmed at all[121] despite their status. However, their organs, including their eyes and optic nerves, are excellently preserved. Chemical analysis of textile samples from their mummies indicate that they were both treated with an embalming recipe. Kha's consists of a mix of animal fat or plant oil and plant-derived extracts, gums, and conifer resin. Merit's is different, consisting of an unusual oil (fish) mixed with plant extracts, gums, resin, and beeswax; similar results, with the addition of Pistacia resin, were obtained from a sample of the red shroud that covered her mummy within the coffin. Both of these embalming recipes were made of costly ingredients that were hard to obtain, some of which were imported into Egypt, and would have had effective anti-bacterial and insecticidal properties. Natron, the main desiccating agent used in mummification, was also utilised within Kha's coffin and appears as white spots on the surface of Merit's wrappings. This study indicates that, contrary to previous opinions, their bodies were indeed embalmed, at significant effort and cost. That the methods used for them differ from the royal mummification method is not surprising, given the difference in status and the economics of Deir el-Medina; Bianucci and co-authors suggest that few in Deir el-Medina would have been mummified in the typical (royal) fashion.[129]

Kha

The mummy of Kha is wrapped in many layers of linen and covered with a linen shroud. The shroud is secured by a double layer of linen bandages running down the centre of the body. This is crossed by four narrow bands at the shoulders, hips, knees, and ankles. Restoration work carried out in the 2000s used a nylon net to consolidate the outer layers of linen, weakened by a previous fungal attack.[130] Kha's mummy is not fitted with a funerary mask. It is generally thought that he donated his mask for his wife's burial[131] but the reason that he did not have another made for his own burial is unknown.[22][132] His body is 1.68 metres (5.5 ft) tall and he lies on his back with his arms extended; his hands are placed over the pubic area.[133]

Kha was 50 to 60 years old at the time of his death, with an estimated height of 1.71 metres (5.6 ft).[134] He was in reasonably good health at the time of his death. His teeth were in poor condition, having lost all the premolars and molars in the upper jaw and several molars in the bottom jaw. He had osteoarthritis in his knees and lower back[135] and many arteries show signs of calcification.[134] His gallbladder contained fourteen gallstones, judged to most likely be pigment stones.[136] His right elbow had an inflammation (enthesopathy) at the insertion point of the triceps brachii.[137] CT examination identified that Kha had fractured his first lumbar vertebra, an injury which left it flattened.[134] Later X-ray analysis considers this injury to have occurred after his death.[137] No attempt was made to remove his organs, which are still in place and are well preserved. There is a large air-filled gap between Kha's torso and the bandage layers, suggesting his body was not fully dried before wrapping.[128] His cause of death is unknown.[137] Despite his sarcophagus being placed in the furthest corner of the tomb, Kha is thought to have died after his wife, as some of his objects were placed in the corridor due to lack of space.[138]

Kha's body is equipped with metal jewellery, likely of gold. Around his neck is a necklace of large gold discs known as a shebyu-collar. This item of jewellery was given by the king as part of the "gold of honour", a reward for service. These necklaces are well known from ancient Egypt, being depicted in many statues and tombs of nobility including those of Sennefer, Ay and Horemheb.[139][140] Kha's collar has only a single strand of beads instead of the usual two, leading to the suggestion that it may be the longer, outermost strand.[141] He wears a pair of large earrings, one of the earliest known ancient Egyptian men to do so.[139] These may also have been part of his royal reward, as similar earrings are depicted, albeit more rarely, in "gold of honour" reward scenes.[142] Kha wears six finger rings; three have fixed oval bezels, one has a fixed rectangular bezel, and two have swiveling bezels of either faience or stone.[143] Further jewellery is purely funerary in nature. These consist of a stone heart scarab on a gold wire or chain, a stone or faience tyet amulet, and a gold foil bracelet around each upper arm.[134] On his forehead is a stone snake head amulet, likely in carnelian or jasper. The usual location of this amulet is around the neck, where it assists in the deceased's ability to breathe in the afterlife. Its placement on his forehead is possibly in imitation of the royal uraeus worn by kings, signaling that the villagers considered Kha the "king" of Deir el-Medina.[143][144]

Merit

After raising the lid, Merit's mummy appeared like a vision, her head and part of the chest covered by a fine gilded mask and the head and body leaning slightly to the left, in the arms of the goddess Nut, painted on the inside of the box, in the languid and weary pose of a person resting and dreaming. The large frozen eyes of the mask, filled with an anguished expression, seemed to be staring at all of us standing around her, as if imploring us to leave her in peace.[124]

Merit's coffin, intended for Kha, is much too large for her and the space around her body was packed with fabric bearing her husband's monogram. A sheet of linen was folded into a pad placed under the mummy and the space under her feet and around her body was filled with eight rolls of bandages.[145] No padding was placed at the head end as the closed coffin would have been placed upright to receive funerary rites so there was no danger of the mummy sliding towards that end. When found, her body lay slanted to her left within the coffin, likely having moved during transport to the tomb.[146] The mummy was wrapped in a further sheet of linen over the top of the shroud, the end of which was tucked under her gilded mummy mask. Her white shroud is stitched up the back with a whip stitch using a thick cord.[145] In 2002 her mummy was sewed into a custom-dyed nylon net to consolidate the fabric.[144]

Unlike Kha, Merit's mummy is fitted with a cartonnage mask. The mask is constructed from eight layers of linen covered in layers of white stucco primer. It has inlaid eyes, of which only one original remains, made of alabaster and obsidian with cosmetic lines and eyebrows of blue paste. The surface is covered in gold leaf now tarnished to a reddish colour, and the striped wig is coloured with Egyptian blue. The broad collar is composed of alternating bands of carnelian, dark blue paste imitating lapis lazuli, and turquoise. The pectoral below the collar is decorated with a blue and red painted vulture on a yellow ground. The mask was probably intended for Kha and was donated by him for his wife's burial. By the time of discovery the mask had sustained some damage, particularly to the back and sides, and one of the inlaid eyes was missing. This may be a result of the mask being much too big for Merit's head, leading to collapse once placed in the coffin.[144] Alternatively, the damage and the missing eye have been attributed to rough handling by Schiaparelli's workmen.[147][148] The mask was restored in 1967 but degraded quickly and further restoration was carried out in 2002, before being placed on a new padded mount in 2004. The back of the mask could not be restored as it was found detached underneath the mummy and had soaked up the oils and resins and flattened by the weight; it is now stored separately.[144]

Merit lies with her arms extended and hands nearly crossed over the pubis. Her age at death is estimated to be between 25 and 35.[128][149] Her body is 1.47 metres (4.8 ft) tall and estimates for her height in life vary between 1.48 metres (4.9 ft)[128] and 1.60 metres (5.2 ft).[149] She wears a long, crimped wig on her head,[126] which is turned slightly to the right. This twist is suggested to be the result of the method of wrapping her head, in which a right handed embalmer pulled on the left side of the bandages to tighten them as he wrapped.[144] Her teeth have little wear but some molars, premolars and a canine have been lost and others have cavities. She is less well-preserved than her husband, with many of her ribs and vertebrae broken and displaced due to postmortem damage to the torso. No attempt was made to remove her brain or other internal organs. Given that she was buried in a coffin intended for Kha, her death was likely unexpected but her cause of death is unknown.[150][128]

Like Kha, her body wears metal jewellery. Around her neck is a triple-strand necklace of fine gold beads; the strings have broken and the beads have scattered, with some being seen by her ankles. Across her chest and shoulders is a gold and stone broad collar similar in design to one from the burial of three foreign wives of Thutmose III[151] and the collars seen on the coffins and mask of Thuya.[152] Her ears are double pierced and she wears two pairs of ribbed hoop earrings. She wears four gold rings on her left hand; a further ring is seen behind her shoulder on X-ray and CT images. This ring has either been displaced from her finger by postmortem damage[151] or was intended for her right hand and forgotten during the wrapping process, being slipped into the shroud before burial.[131] A second gold ring was found during conservation work, stuck to the back of her mask in the embalming resins. The bezel is incised with an image of a Hathor-cow wearing a menat necklace and standing on a boat under a palm tree. This design is similar to a ring found on the body of Nefertity in tomb DM1159a.[131] Around her waist is a beaded girdle of metal cowrie shell-shaped beads interspersed with strings of small non-metal beads. Cowries are associated with fertility[131] and similar girdles are known from the burials of Sithathoriunet and three of Thutmose III's foreign wives. On each wrist are ten-stranded bracelets of metal and non-metal beads with a sliding catch. They appear to have the same design as the necklace and girdle and probably formed part of a set.[151][131] Merit was not equipped with any funerary amulets, possibly due to her unexpected death.[151]

The mummy of Merit with cartonnage mask, wrapped in her outer shroud

The mummy of Merit with cartonnage mask, wrapped in her outer shroud The mummy of Merit

The mummy of Merit

Other funerary equipment

Kha's copy of the Book of the Dead, some 13 metres (43 ft) long, was found laid out atop his outer mummiform coffin. At the time of its discovery it was "perfectly conserved and as supple as if recently made".[115] It is one of the earliest copies known,[153] and the only one found in Deir el-Medina dating to the Eighteenth Dynasty.[154] It features colourful vignettes in which Kha is depicted generically, showing less customization than in the copies of Yuya and Maiherpri. It is written in cursive hieroglyphs which are closer in style to Maiherpri's[153] but the composition is more similar to Yuya's. It is unique within the known Eighteenth Dynasty examples for including Chapter 175. A second copy of the Book of the Dead belonging to Kha is now in the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris but its provenance is unknown.[154] It may originally have come from the pit Bruyère found in front of their chapel. This copy was likely intended for Merit as her name appears more often than Kha's, a unique instance in the Eighteenth Dynasty of a woman being provided with her own copy. Alternatively, it could be a separate copy which ultimately went unused and was put aside for reuse.[155]

A wooden ka statuette was placed in the tomb, standing on a chair. The 43 cm (17 in) tall figure depicts a youthful Kha wearing a kilt, striding forward. The eyes and wig are painted and the column of text down the front of his kilt is filled with yellow pigment but the surface is otherwise plain. The inscription asks that his ka may receive "all that appears on the table of offerings to Amun, king of the gods".[156] Around the shoulders of the figure was a garland of melilot leaves; another was folded at its feet.[156] The rectangular base is also inscribed with an offering formula ensuring Kha received the standard bread, beer, ox and fowl with the additional alabaster, linen, wine, and milk.[157] This item is not without parallel as there are occasional examples from other contemporary non-noble Theban tombs. However, given the number of similar wooden statuettes known, this practice was likely much more common. Such figures are generally absent from contemporary elite (robbed) burials, possibly indicating they were made of valuable metal and looted by ancient robbers.[158]

Kha was provided with two ushabti for his use in the afterlife. One is made of stone and the other is wooden and was provided with its own miniature sarcophagus and agricultural tools. These were placed immediately behind and in front of the statuette.[156][159] Merit was not given any ushabti. This inequality between the spouses is not unusual as a similar imbalance is seen in the burial of Yuya and Thuya.[146]

Location and display of objects

Following the discovery, Gaston Maspero, director of the Antiquities Service, awarded the vast majority of the contents of TT8 to the excavators. They are housed today in the Museo Egizio in Turin. The Egyptian Museum in Cairo retained few objects from the tomb, keeping one of the two lamp stands, loaves of bread, three blocks of salt, and nineteen pottery vases.[37] This may be because Maspero considered the contents of TT8 to be duplicates or not unlike anything already in the museum's collection.[160][161]

The contents of the tomb have been displayed since their arrival in Italy. Within months of arriving, the change in humidity affected the leather seats of the stools and the Book of the Dead, rendering them both fragile and cracked.[148] The objects were displayed within a single small room, refurbished in the 1960s, which gave visitors "a good idea of the place at the moment of discovery".[123][162] They were moved to a larger gallery in the 2000s, and redisplayed again in 2015 in an even more spacious gallery after the Museo Egizio underwent extensive renovations.[162]

Notes

- ↑ The chapel has the number TT8. The standard numbering system for private tombs in the Theban necropolis was implemented by the Antiquities Service in the early 1900s and published by the Egyptologists Alan Gardiner and Arthur Weigall in 1913. Tombs and chapels discovered later were added in sequence.[30][31] Kha and Merit's burial chamber, located separately from their chapel, was initially given the tomb number 269 before being connected with the existing chapel number.[32]

- ↑ Kha and Merit are presumed to have lived in Deir el-Medina.[92] No house can be definitely assigned to the couple. Vassilika and Russo consider the possibility that they lived temporarily in the village during work periods and had a separate residence elsewhere, based on the large quantity of furniture and the small house sizes in the workmen's village.[60][93]

References

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 5 Porter & Moss 1960, pp. 16–18.

- ↑ Eaton-Krauss 1999.

- 1 2 3 4 5 La Nasa et al. 2022, p. 1.

- ↑ Reeves & Wilkinson 1996, p. 18.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Bianucci et al. 2015, p. 4.

- ↑ Ferraris 2018, p. 12.

- 1 2 Russo 2012, p. 67.

- ↑ Töpfer 2019, p. 12.

- ↑ Russo 2012, pp. 22, 77.

- ↑ Trapani 2015, p. 2221.

- 1 2 Forbes 1998, p. 112.

- ↑ Schiaparelli 2008, p. 60.

- 1 2 Trapani 2012, p. 167.

- ↑ Russo 2012, p. 73.

- 1 2 Russo 2012, pp. 67–69.

- ↑ Vassilika 2010, p. 7.

- ↑ Russo 2012, p. 70.

- ↑ Laboury 2023, p. 127.

- ↑ Russo 2012, pp. 23, 31.

- ↑ Binder 2008, p. 240.

- ↑ Russo 2012, pp. 24, 31.

- 1 2 3 4 Forbes 1998, p. 113.

- ↑ Forbes 1998, p. 102.

- ↑ Russo 2012, pp. 63, 78.

- 1 2 Martina et al. 2005, p. 42.

- ↑ Koltsida 2007, p. 125.

- 1 2 Trapani 2015, pp. 2221–2222.

- 1 2 Russo 2012, p. 66.

- ↑ Forbes 1998, p. 132.

- ↑ Porter & Moss 1960, p. vii.

- ↑ Gardiner & Weigall 1913.

- 1 2 Bruyère 1925.

- 1 2 Vandier d'Abbadie 1939, p. 2.

- ↑ Bruyère 1924, p. 53.

- 1 2 Meskell 1998, p. 371.

- 1 2 Russo 2012, p. 64.

- 1 2 3 4 Sousa 2019, p. 63.

- 1 2 Forbes 1998, p. 135.

- 1 2 Ferraris 2022, p. 610.

- ↑ Bruyère 1924, pp. 51–54.

- 1 2 3 Hobson 1987, pp. 118–119.

- 1 2 Vandier d'Abbadie 1939, p. 4.

- ↑ Schiaparelli 2008, p. 56.

- ↑ Bruyère 1925, pp. 53–55.

- ↑ Russo 2012, p. 22.

- ↑ Laboury 2023, pp. 126–127.

- ↑ Vandier d'Abbadie 1939, p. 1.

- ↑ Schiaparelli 2008, p. 58.

- 1 2 Vandier d'Abbadie 1939, p. 5.

- ↑ Porter & Moss 1960, p. 1618.

- ↑ Vandier d'Abbadie 1939, pp. 5–7.

- ↑ Vandier d'Abbadie 1939, p. 7.

- 1 2 3 Schiaparelli 2008, p. 57.

- 1 2 Sousa 2019, p. 64.

- ↑ Vandier d'Abbadie 1939, p. 8.

- ↑ Vandier d'Abbadie 1939, pp. 5, 8.

- 1 2 Bianucci et al. 2015, p. 2.

- ↑ Del Vesco & Poole 2018, pp. 98–99.

- ↑ Eaton-Krauss 1999, pp. 127–128.

- 1 2 Vassilika 2010, p. 10.

- 1 2 Russo 2012, p. 4.

- ↑ Del Vesco & Poole 2018, p. 107.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Schiaparelli 2008, pp. 15–17.

- ↑ Vassilika 2010, p. 22.

- ↑ Weigall 1911, pp. 178–179.

- 1 2 Weigall 1911, p. 178.

- 1 2 Weigall 1911, p. 180.

- ↑ Forbes 1998, p. 61.

- ↑ Forbes 1998, p. 114.

- ↑ Vassilika 2010, pp. 25–26.

- ↑ Vassilika 2010, pp. 22–23.

- ↑ Vassilika 2010, pp. 13–16.

- ↑ Weigall 1911.

- 1 2 3 4 Schiaparelli 2008, pp. 28–33.

- ↑ Meskell 1998, p. 372.

- ↑ Nishimoto 2017, p. 450.

- ↑ Sousa 2019, p. 73.

- ↑ Russo 2012, p. 11.

- ↑ Russo 2012, p. 45.

- ↑ Russo 2012, pp. 46–47.

- ↑ Russo 2012, pp. 22–23.

- ↑ Russo 2012, pp. 36, 77.

- ↑ Russo 2012, pp. 19–20.

- ↑ Russo 2012, p. 18.

- 1 2 Schiaparelli 2008, p. 33.

- ↑ Meskell 1998, p. 376.

- 1 2 Buckley & Fletcher 2016.

- ↑ Forbes 1998, p. 85.

- 1 2 Schiaparelli 2008, pp. 33–34.

- ↑ Forbes 1998, pp. 84–85.

- ↑ Forbes 1998, pp. 86–87.

- ↑ Forbes 1998, p. 88.

- ↑ Russo 2012, p. 65.

- ↑ Schiaparelli 2008, pp. 37–40.

- ↑ Forbes 1998, pp. 87–92.

- ↑ Forbes 1998, p. 93.

- ↑ Schiaparelli 2008, p. 44.

- ↑ Wilkinson 1992, p. 111.

- ↑ Schiaparelli 2008, pp. 43–44.

- ↑ Forbes 1998, pp. 92–93.

- ↑ Schiaparelli 2008, pp. 46–47.

- 1 2 Schiaparelli 2008, pp. 46–50.

- 1 2 Forbes 1998, pp. 105–108.

- ↑ Shahat 2019, p. 69-70.

- ↑ Festa et al. 2021.

- ↑ La Nasa et al. 2022.

- ↑ Forbes 1998, p. 63.

- ↑ Forbes 1998, p. 144.

- 1 2 3 Schiaparelli 2008, p. 19.

- ↑ Forbes 1998, pp. 63–64.

- ↑ Bianucci et al. 2015, p. 15.

- ↑ Forbes 1998, p. 64.

- 1 2 Kozloff 1998, p. 118.

- ↑ Forbes 1998, pp. 65–68.

- 1 2 3 4 Schiaparelli 2008, p. 20.

- ↑ Kozloff 1998, pp. 118–119.

- ↑ Schiaparelli 2008, pp. 21–22.

- ↑ Schiaparelli 2008, p. 21.

- 1 2 Sousa 2019, p. 80.

- ↑ Bettum 2018, p. 285.

- 1 2 Meskell 1998, p. 373.

- ↑ Sousa 2019, p. 89.

- 1 2 Curto & Mancini 1968, p. 77.

- 1 2 Schiaparelli 2008, p. 22.

- ↑ Bianucci et al. 2015, pp. 4–6.

- 1 2 Gordan-Rastelli 2019, p. 51.

- ↑ Bianucci et al. 2015, p. 3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Martina et al. 2005, p. 44.

- ↑ Bianucci et al. 2015, pp. 16–18.

- ↑ Marochetti et al. 2005, p. 243.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Marochetti et al. 2005, p. 246.

- ↑ Casini 2017, p. 66.

- ↑ Bianucci et al. 2015, p. 6.

- 1 2 3 4 Martina et al. 2005, p. 43.

- ↑ Bianucci et al. 2015, pp. 6–7.

- ↑ Cesarani et al. 2009, p. 1194.

- 1 2 3 Bianucci et al. 2015, p. 7.

- ↑ Forbes 1998, p. 113, 144.

- 1 2 Bianucci et al. 2015, pp. 12–13.

- ↑ Brand 2006, pp. 17–18.

- ↑ Binder 2008, p. 43.

- ↑ Trapani 2015, pp. 2222–2223.

- 1 2 Bianucci et al. 2015, p. 13.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Marochetti et al. 2005, p. 245.

- 1 2 Marochetti et al. 2005, p. 244.

- 1 2 Forbes 1998, p. 75.

- ↑ Curto & Mancini 1968, pp. 77–78.

- 1 2 Vassilika 2010, p. 27.

- 1 2 Bianucci et al. 2015, p. 9.

- ↑ Bianucci et al. 2015, pp. 9–11.

- 1 2 3 4 Bianucci et al. 2015, pp. 14–15.

- ↑ Russo 2012, p. 31.

- 1 2 Forbes 1998, p. 121.

- 1 2 Trapani 2012, p. 166.

- ↑ Vassilika 2010, p. 77.

- 1 2 3 Schiaparelli 2008, p. 26.

- ↑ Sousa 2019.

- ↑ Smith 1992, p. 200.

- ↑ Sousa 2019, pp. 74–75.

- ↑ Forbes 1998, pp. 61–63.

- ↑ Vassilika 2010, p. 24.

- 1 2 Forbes 1998, pp. 114–115.

Works cited

- Bettum, Anders (2018). "Nesting (Part Two): Merging of Coffin Layers in New Kingdom Coffin Decoration". In Taylor, John H.; Vandenbeusch, Marie (eds.). Ancient Egyptian Coffins: Craft Traditions and Functionality. Leuven: Peeters. pp. 275–291. ISBN 978-90-429-3465-8.

- Bianucci, Raffaella; Habicht, Michael E.; Buckley, Stephen; Fletcher, Joann; Seiler, Roger; Öhrström, Lena M.; Vassilika, Eleni; Böni, Thomas; Rühli, Frank J. (22 July 2015). "Shedding New Light on the 18th Dynasty Mummies of the Royal Architect Kha and His Spouse Merit". PLOS ONE. 10 (7): e0131916. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1031916B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0131916. PMC 4511739. PMID 26200778.

- Binder, Susanne (2008). The Gold of Honour in New Kingdom Egypt. Oxford: Aris and Phillips. ISBN 978-0-85668-899-7.

- Brand, Peter (2006). "The Shebyu-Collar in the New Kingdom Part I". Studies in Memory of Nicholas B. Millet (Journal of the Society for the Study of Egyptian Antiquities). 33: 17–28. Retrieved 16 April 2023.

- Bruyère, Bernard (1924). "Rapport sur les Fouilles de Deir El Médineh (1922–1923)". Fouilles de l'Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale (in French). Institut français d'archéologie orientale. 1 (1). Retrieved 31 January 2022.

- Bruyère, Bernard (1925). "Rapport sur les Fouilles de Deir El Médineh (1923–1924)". Fouilles de l'Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale (in French). Institut français d'archéologie orientale. 2 (2). Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- Buckley, Stephen; Fletcher, Joann (21 November 2016). "The Hair and Wig of Meryt: Grooming in the 18th Dynasty". Internet Archaeology (42). doi:10.11141/ia.42.6.4. ISSN 1363-5387. Retrieved 2 October 2022.

- Casini, Emanuele (2017). "Remarks on Ancient Egyptian Cartonnage Mummy Masks from the Late Old Kingdom to the End of the New Kingdom". In Chyla, Julia M.; Dębowska-Ludwin, Joanna; Rosińska-Balik, Karolina; Walsh, Carl (eds.). Current Research in Egyptology 2016: Proceedings of the Seventeenth Annual Symposium. Oxford: Oxbow Books. pp. 56–73. ISBN 978-1-78570-600-4.

- Cesarani, Federico; Martina, Maria Cristina; Boano, Rosa; Grilletto, Renato; D’Amicone, Elvira; Venturi, Claudio; Gandini, Giovanni (1 July 2009). "Multidetector CT Study of Gallbladder Stones in a Wrapped Egyptian Mummy". RadioGraphics. 29 (4): 1191–1194. doi:10.1148/rg.294085246. ISSN 0271-5333. PMID 19605665. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- Curto, Silvio; Mancini, M. (1968). "News of Kha' and Meryt". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 54: 77–81. doi:10.2307/3855908. JSTOR 3855908. Retrieved 7 January 2023.

- Del Vesco, Paolo; Poole, Federico (2018). "Deir el-Medina in the Egyptian Museum of Turin. An Overview, and the Way Forward". In Dorn, Andreas; Polis, Stéphane (eds.). Outside the Box: Selected Papers from the Conference "Deir el-Medina and the Theban Necropolis in Contact" Liège, 27–29 October 2014. Liège: Presses Universitaires de Liège. pp. 97–130. ISBN 978-2-87562-166-5. Retrieved 24 November 2022.

- Eaton-Krauss, M. (1999). "The Fate of Sennefer and Senetnay at Karnak Temple and in the Valley of the Kings". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 85: 113–129. doi:10.2307/3822430. JSTOR 3822430.

- Ferraris, Enrico (2018). La Tomba di Kha e Merit (in Italian) (eBook ed.). Modena: Franco Cosimo Panini. ISBN 9788857014388.

- Ferraris, Enrico (2022). "TT8 Project: An Introduction". Deir el-Medina: Through the Kaleidoscope; Proceedings of the International Workshop Turin 8th-10th October 2018. Turin: Museo Egizio. pp. 599–619. ISBN 9788857018300.

- Festa, G.; Saladino, M. L.; Mollica Nardo, V.; Armetta, F.; Renda, V.; Nasillo, G.; Pitonzo, R.; Spinella, A.; Borla, M.; Ferraris, E.; Turina, V.; Ponterio, R. C. (9 February 2021). "Identifying the Unknown Content of an Ancient Egyptian Sealed Alabaster Vase from Kha and Merit's Tomb Using Multiple Techniques and Multicomponent Sample Analysis in an Interdisciplinary Applied Chemistry Course". Journal of Chemical Education. 98 (2): 461–468. Bibcode:2021JChEd..98..461F. doi:10.1021/acs.jchemed.0c00386. hdl:10447/530775. ISSN 0021-9584. S2CID 230616659. Retrieved 4 February 2022.

- Forbes, Dennis C. (1998). Tombs. Treasures. Mummies : Seven Great Discoveries of Egyptian Archaeology in Five Volumes. Book Two, The Tombs of Maiherpri (KV36) & Kha & Merit (TT8) (2015 Reprint ed.). Weaverville: Kmt Communications LLC. ISBN 978-1512371956.

- Gardiner, Alan H.; Weigall, Arthur E. P. (1913). A Topographical Catalogue of the Private Tombs of Thebes. London: Bernard Quaritch.

- Gordan-Rastelli, Lucy (2019). "Invisible Archaeology: Beyond the Naked Eye". KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt. 30 (3): 39–54. Archived from the original on 7 January 2023.

- Hobson, Christine (1987). The World of the Pharaohs: A Complete Guide to Ancient Egypt (1993 paperback ed.). New York: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 9780500275603.

- Koltsida, Aikaterini (2007). "Domestic Space and Gender Roles in Ancient Egyptian Village Households: A View from Amarna Workmen's Village and Deir el-Medina". British School at Athens Studies. 15: 121–127. ISSN 2159-4996.

- Kozloff, Arielle P. (1998). "The Decorative and Funerary Arts During the Reign of Amenhotep III". In O'Connor, David; Cline, Eric H. (eds.). Amenhotep III: Perspectives on His Reign. United States of America: The University of Michigan Press. pp. 95–123. ISBN 0-472-10742-9.

- Laboury, Dimitri (2023). "On the Alleged Involvement of the Deir el-Medina Crew in the Making of Elite Tombs in the Theban Necropolis During the Eighteenth Dynasty: A Reassessment". In Bryan, Betsy M.; Dorman, Peter F. (eds.). Mural Decoration in the Theban Necropolis. United States of America: University of Chicago. pp. 115–138. ISBN 978-1-61491-089-3.

- La Nasa, Jacopo; Degano, Ilaria; Modugno, Francesca; Guerrini, Camilla; Facchetti, Federica; Turina, Valentina; Carretta, Andrea; Greco, Christian; Ferraris, Enrico; Colombini, Maria Perla; Ribechini, Erika (May 2022). "Archaeology of the Invisible: The Scent of Kha and Merit". Journal of Archaeological Science. 141: 105577. Bibcode:2022JArSc.141j5577L. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2022.105577. S2CID 247374925.

- Marochetti, Elisa Fiore; Oliva, Cinza; Doneux, Kristine; Curti, Alessandra; Janot, Francis (2005). "The Mummies of Kha and Merit: Embalming Ritual and Restauration[sic] Work". Journal of Biological Research – Bollettino della Società Italiana di Biologia Sperimentale. 80 (1): 243–247. doi:10.4081/jbr.2005.10195. S2CID 239503089. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- Martina, Maria Cristina; Cesarani, Federico; Boano, Rosa; Donadoni Roveri, Anna Maria; Ferraris, Andrea; Grilletto, Renato; Gandini, Giovanni (2005). "Kha and Merit: Multidetector Computed Tomography and 3D Reconstructions of Two Mummies from the Egyptian Museum of Turin". Journal of Biological Research – Bollettino della Società Italiana di Biologia Sperimentale. 80 (1). doi:10.4081/jbr.2005.10088. S2CID 86115996. Retrieved 8 January 2023.

- Meskell, Lynn (1998). "Intimate Archaeologies: The Case of Kha and Merit". World Archaeology. 29 (3): 363–379. doi:10.1080/00438243.1998.9980385. ISSN 0043-8243. JSTOR 125036. Retrieved 1 February 2022.

- Nishimoto, Naoko (2017). "The Folding Cubit Rod of Kha in Museo Egizio di Torino, S.8391". In Rosati, Gloria; Guidotti, Maria Cristina (eds.). Proceedings of the XI International Congress of Egyptologists: Florence Egyptian Museum Florence, 23–30 August 2015. Oxford: Archaeopress Publishing Limited. pp. 450–456. ISBN 978-1-78491-600-8. Retrieved 24 November 2022.

- Porter, Bertha; Moss, Rosalind L. B. Moss (1960). Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Reliefs, and Paintings I: The Theban Necropolis Part 1. Private Tombs (PDF) (1970 reprint ed.). Oxford: Griffith Institute. Retrieved 4 February 2022.

- Reeves, Nicholas; Wilkinson, Richard H. (1996). The Complete Valley of the Kings: Tombs and Treasures of Egypt's Greatest Pharaohs (2010 paperback ed.). London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-28403-2.

- Russo, Barbara (2012). Kha (TT 8) and His Colleagues: The Gifts in His Funerary Equipment and Related Artefacts from Western Thebes. London: Golden House Publications. ISBN 978-1-906137-28-1.

- Schiaparelli, Ernesto (2008) [1927]. La Tomba Intatta Dell'architetto Kha Nella Necropoli Di Tebe: The Intact Tomb of the Architect Kha in the Necropolis of Thebes (in Italian and English). Translated by Fisher, Barbara. Turin: AdArte. ISBN 9788889082096.

- Shahat, Amr Khalaf (2019). "An Archaeobotanical Study of the Food in the Tomb of Kha and Merit". Backdirt: Cotsen Institute of Archaeology: 68–71.

- Smith, Stuart Tyson (1992). "Intact Theban tombs and the New Kingdom burial assemblage". Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Abteilung Kairo. 48: 193–231. Retrieved 14 November 2022.

- Sousa, Rogerio (19 December 2019). Gilded Flesh: Coffins and Afterlife in Ancient Egypt. Oxbow Books. ISBN 978-1-78925-263-7.

- Töpfer, Susanne (2019). Il Libro dei Morti di Kha (in Italian). Turin: Museo Egizio. ISBN 9788857015095. Retrieved 14 November 2022.

- Trapani, Marcella (2012). "Behind the Mirror: Art and Prestige in Kha's Funerary Equipment". In Kóthay, Katalin Anna (ed.). Art and Society. Ancient and Modern Contexts of Egyptian Art. Budapest: Museum of Fine Arts. pp. 159–168. ISBN 978-963-7063-91-6. Retrieved 13 November 2022.

- Trapani, Marcella (2015). "Kha's Funerary Equipment at the Egyptian Museum in Turin: Resumption of the Archaeological Study". In Kousoulis, P.; Lazaridis, N. (eds.). Proceedings of the Tenth International Congress of Egyptologists, University of the Aegean, Rhodes, 22–29 May 2008 (Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta 241) Volume II. Leuven: Peeters. pp. 2217–2232. ISBN 978-90-429-2550-2. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- Vandier d'Abbadie, Jeanne Marie Thérèse (1939). "Deux Tombes de Deir El Médineh (1) La Chapelle de Khâ (2) La tombe du scribe royal Amenemopet (1939)". Mémoires Publiés par les Membres de l'Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale (in French). Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale. 73: 1–18. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- Vassilika, Eleni (2010). The Tomb of Kha: The Architect. Torino: Fondazione Museo delle Antichità Egizie di Torino. ISBN 9788881171286.

- Weigall, Arthur E. P. B. (1911). The Treasury of Ancient Egypt. Edinburgh and London: William Blackwood and Sons. Retrieved 12 July 2021.

- Wilkinson, Richard H. (1992). Reading Egyptian Art: A Hieroglyphic Guide to Ancient Egyptian Painting and Sculpture (1998 ed.). London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-27751-6. Retrieved 2 October 2022.

External links

- Virtual reconstruction of tomb as discovered

- Virtual tour of the Deir el-Medina and Tomb of Kha galleries

- Archeologia Invisibile exhibition featuring the mummies of Kha and Merit, and 3D printed replicas of their jewellery (in Italian)

- Bibliography of TT8 on the Theban Mapping Project (archived)

- Scans of tracings of parts of TT8 chapel paintings by N. de Garis Davies