| Valley of the Queens وادي الملكات (Arabic) Ta-Set-Neferu (Egyptian) | |

|---|---|

General view of the Valley of the Queens | |

| Location | Luxor, Egypt |

| Coordinates | 25°43′39″N 32°35′35″E / 25.72750°N 32.59306°E |

| Official name | Ancient Thebes with its Necropolis |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, iii, vi |

| Designated | 1979 (third session) |

| Reference no. | 87 |

| Region | Arab states |

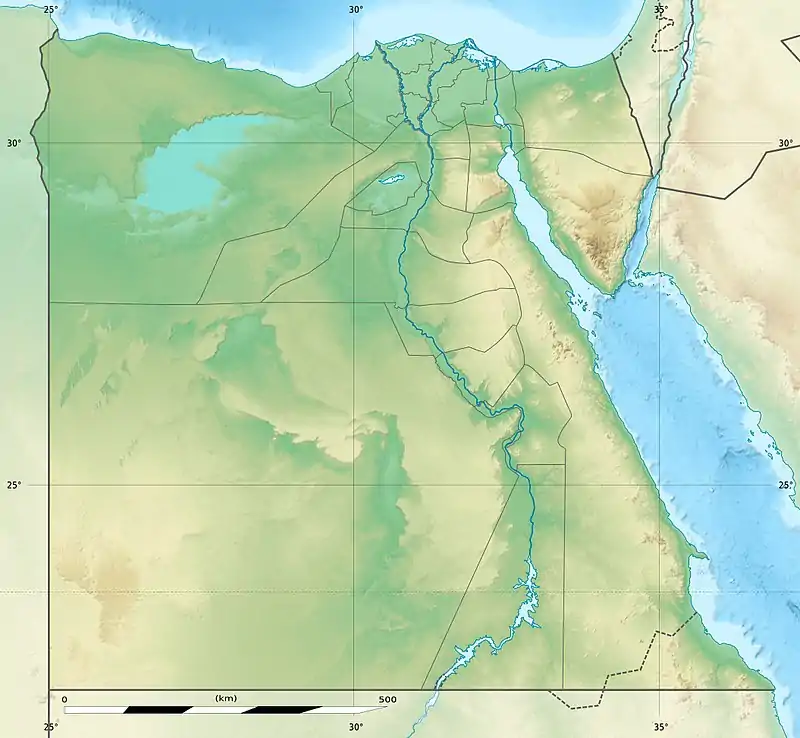

Location within Egypt | |

| Valley of the Queens in hieroglyphs | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Ta-set-neferu T3-st-nfrw The place of beauty | ||||||||

The Valley of the Queens (Arabic: وادي الملكات Wādī al-Malekāt) is a site in Egypt, in which queens, princes, princesses, and other high ranking officials were buried. Pharaohs themselves were buried in the Valley of the Kings. The Valley of the Queens was known anciently as Ta-Set-Neferu, which has a double meaning of "The Place of Beauty" and/or "the Place of the Royal Children".[1] Excavation of the tombs at the Valley of the Queens was pioneered by Ernesto Schiaparelli and Francesco Ballerini in the early 1900s.[2]

The Valley of the Queens consists of the main wadi, which contains most of the tombs, along with the Valley of Prince Ahmose, the Valley of the Rope, the Valley of the Three Pits, and the Valley of the Dolmen. The main wadi contains 91 tombs and the subsidiary valleys add another 19 tombs. The burials in the subsidiary valleys all date to the 18th Dynasty.[3]

The reason for choosing the Valley of the Queens as a burial site is not known. The close proximity to the workers' village of Deir el-Medina and the Valley of the Kings may have been a factor. Another consideration could have been the existence of a sacred grotto dedicated to Hathor at the entrance of the Valley. This grotto may have been associated with rejuvenation of the dead.[3]

Along with the Valley of the Kings and nearby Thebes, the Valley of the Queens was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1979.[4]

Geology

The Valley of the Queens is on a geological array of limestones, marls, clays, chalks, and shale. The clays in the valley have undergone expansion and shrinkage due to recurrent flash-flooding throughout the valley. This shrinkage has been one cause of unstable tomb construction and later tomb damage in the valley. Rockslides resulting from shrunk clay deposits and tectonic events have damaged not only the tombs of the valley but also the wall paintings within them.[5]

The current landscape of the Valley of the Queens was built through faulting and subsequent slumping during the Pliocene and Pleistocene epochs. Thus, the original horizontal stratigraphy of the area has been subject to tilting. This tilting has revealed deposits of minerals like anhydrite, gypsum, and halite. Salt from halite in the ground is also damaging to the paintings within tombs. Seeping groundwater has permeated the tombs and is the cause of the dissolved and recrystallized salt.[5]

Gypsum, along with clay, is most often believed to be the plasters used in ancient Egypt. Due to the lack of data, however, it is hard to determine what exactly composes the ancient plasters. Such beliefs are contested because of variations of plaster color, hardness, and amount used in a particular tomb.[6]

Eighteenth Dynasty

One of the first tombs constructed in the Valley of the Queens is the tomb of Princess Ahmose, a daughter of Seqenenre Tao and Queen Sitdjehuti. This tomb likely dates to the reign of Thutmose I. The tombs from this period also include several members of the nobility, including a head of the stables and a vizier.[3]

The tombs from the Valley of the Three Pits mostly date to the Thutmosid period. The tombs are labeled with letters A - L. This valley also contains three shaft tombs, which are the origin of the valley's name. The modern labels for these three tombs are QV 89, QV 90, and QV 91.[3]

The Valley of the Dolmen contains an old trail used by the workmen traveling from Deir el-Medina to the Valley of the Queens. Along this path is a small rock-cut temple dedicated to Ptah and Meretseger.[3]

The tombs from this time period are generally simple in form and consist of a chamber and a shaft for burial. Some of the tombs were extended in size to accommodate more than one burial. The tombs include those of several royal princes and princesses, as well as some nobles.[3]

A tomb of the Princesses was located in the Valley. This tomb dates to the time of Amenhotep III. Its location is currently unknown, but finds from the tomb are in museums and include fragments of burial equipment for several members of the royal family.[7] The items include a canopic jar fragment of the King's Wife Henut. She is thought to have lived mid-18th Dynasty. Her name was enclosed in a cartouche. Canopic jar fragments mentioning Prince Menkheperre, a son of Tuthmosis III and Merytre Hatshepsut, were found. A King's Great Wife Nebetnehat from the mid-18th Dynasty is attested because her name was enclosed in a cartouche on canopic fragments. Canopic jar fragments with the name of the King's Daughter Ti from the mid-18th Dynasty were found as well.[8][9]

Nineteenth Dynasty

During the 19th Dynasty the use of the Valley became more selective. The tombs from this period belong exclusively to royal women. Many of the high-ranking wives of Ramesses I, Seti I and Ramesses II were buried in the Valley. One of the most well-known examples is the resting place carved out of the rock for Queen Nefertari (1290–1224 BCE). The polychrome reliefs in her tomb are still intact. Other members of the royal family continued to be buried in the Valley of the Kings. Tomb KV5, the tomb of the sons of Ramesses II, is an example of this practice.[3]

The tomb of Queen Satre (QV 38) was likely the first tomb prepared during this dynasty. It was probably started during the reign of Ramesses I and finished during the reign of Seti I. Several tombs were prepared without an owner in mind, and the names were included upon the death of the royal female.[3]

Twentieth Dynasty

During the beginning of the 20th Dynasty the Valley was still used extensively. Tombs for the wives of Ramesses III were prepared, and in a departure from the conventions of the previous dynasty, several tombs were prepared for royal sons as well. The construction of tombs continued at least until the reign of Ramesses VI. The Turin Papyrus mentions the creation of six tombs during the reign of Ramesses VI. It is not known which tombs are referred to in that papyrus.[3]

There is evidence of economic turmoil during the 20th Dynasty. Records show that the workers went on strike during the reign of Ramesses III, and towards the end of the dynasty there are reports of tomb robberies.[3]

Third Intermediate Period and later

The Valley was no longer a royal burial site after the close of the 20th Dynasty. Many of the tombs were extensively reused. Several tombs were modified so that they could hold multiple burials. In some cases this involved digging burial pits in the existing tombs. Not much is known about the use of the Valley of the Queens during the Ptolemaic Period but during the Roman Period there was a renewed, extensive use of the Valley as a burial site. During the Coptic Period some Hermit shelters were erected. Tombs QV60 (Nebettawy) and QV73 (Henuttawy) show signs of Coptic occupation. Wall scenes were covered with plaster and decorated with Christian symbols. The Christian presence lasted until the 7th century CE.[3]

Threats to Conservation

Conservation efforts in the Valley of the Queens happen in multiple ways. Some large concerns for the site include protection against mass tourism and a concoction of other natural risks.

Mass Tourism

With the rise of the tourism industry, affects humans have on archaeological sites is becoming a topic of interest for preservation teams. The relatively small size and delicate ecosystem of many of the Valley of the Queens tombs are threatened by human interaction. An off balance of humidity and CO2 from humans contributes to the continued degradation of tombs and the art within them. Other factors that lead to tomb deterioration are graffiti, touching, and head bumping due to small spaces.[10]

Light fixtures installed in some of the tombs for better viewing are also a threat to conservation efforts in the area. Large amounts of lint from visitors' clothes stays in the air and settles on tomb floors and other fixtures, creating an increased fire hazard. As lint settles on the modern light fixtures, the likeliness of combustion increases.[10]

Steps taken to combat and limit affects on Valley of the Queens tombs from tourism comprise of building walled paths that control tourist traffic, constructing shelters at some of the more popular tombs such as QV 66 - Nefertari's tomb. Other methods used to preserve Nefertari's tomb are a viewing time limited to 15 minutes, separate ticket purchase, and the addition of an air-circulation system to the tomb. As for other tombs, plexiglass shields and wooden floors have been installed to protect the entombed and their resting places.[11]

Animal Populations

Commonly located in open tombs in the Valley of the Queens is small to large bat colonies. Although beneficial for the natural ecosystem, bats are detrimental to the tombs, the wall paintings, and the health of tourists in the valley. Urine and feces from bats damages the rocks, plasters, and paints used for tomb construction and decoration. Also stemming from bat excrement is the increased possibility of visitors getting histoplasmosis. Contact with bat populations also increases the possibility of bat bites and rabies transmission.[10]

In an attempt to limit bat occupation of certain tombs, instillation of doors and has been proposed. Bat populations must be removed from the tombs before any preventative measures can be taken.[12] Due to ecological importance, some tombs have been selected to remain open to bat colonies. Tombs selected are as follows: QV 15, QV 48, AND QV 78.[10]

Burials

References

- ↑ "The Valley of the Queens and the Western Wadis". Theban Mapping Project.

- ↑ "Schiaparelli, Ernesto". Theban Mapping Project.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Demas, Martha, and Neville Agnew, eds. 2012. Valley of the Queens Assessment Report: Volume 1. Los Angeles, CA: Getty Conservation Institute. Getty Conservation Institute, link to article

- ↑ "Ancient Thebes with its Necropolis". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- 1 2 Demas, Martha; Agnew, Neville (2016). "Valley of the Queens Assessment Report: Volume 1". The Getty Conservation Institute.

- ↑ Wong, Lori; Rickerby, Stephen; Rava, Amarilli; Sharkawi, Alaa El-Din (2012). "Developing Approaches for Conserving Painted Plasters in the Royal Tombs of the Valley of the Queens". ResearchGate.

- ↑ Dodson A. and Hilton D. The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt, London 2004

- ↑ Porter, Bertha and Moss, Rosalind, Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Statues, Reliefs and Paintings Volume I: The Theban Necropolis, Part 2. Royal Tombs and Smaller Cemeteries, Griffith Institute. 1964, pp. 766–767

- ↑ "QV 30 Nebiri". Theban Mapping Project. Retrieved April 30, 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 Demas, Martha; Agnew, Neville (2016). "Valley of the Queens Assessment Report: Volume 1". The Getty Conservation Institute.

- ↑ "The Valley of the Queens and the Western Wadis". Theban Mapping Project.

- ↑ Demas, Martha; Agnew, Neville (2016). "Valley of the Queens Assessment Report: Volume 2." The Getty Conservation Institute.

Bibliography

- Sims, Lesley (2000). A Visitor's Guide to Ancient Egypt. Saffron Hill, London: Usborne Publishing. ISBN 0746030673.

Sources

- Bunson, Margaret (1991). "Valley of the Queens". Encyclopædia of Ancient Egypt. New York. ISBN 9780816020935.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

External links

- Theban Mapping Project – Includes descriptions, images and plans of most of the tombs.

- "Tour Egypt: Valley of the Queens in Thebes, Egypt". Retrieved 27 March 2013.

- "Getty Conservation Institute: Valley of the Queens". Retrieved 27 March 2013.