| Accident | |

|---|---|

| Date | January 16, 1942 |

| Summary | Controlled flight into terrain due to pilot error |

| Site | Potosi Mountain, Nevada, U.S. 35°57′04″N 115°29′29″W / 35.9510°N 115.4914°W |

| Aircraft type | Douglas DC-3 |

| Operator | Transcontinental and Western Air |

| Registration | NC1946 |

| Flight origin | New York, New York, U.S. |

| 1st stopover | Indianapolis, Indiana, U.S. |

| 2nd stopover | St. Louis, Missouri, U.S. |

| 3rd stopover | Albuquerque, New Mexico, U.S. |

| 4th stopover | Las Vegas Airport, Las Vegas, Nevada, U.S. |

| Destination | Burbank, California, U.S. |

| Occupants | 22 |

| Passengers | 19 |

| Crew | 3 |

| Fatalities | 22 |

| Survivors | 0 |

TWA Flight 3 was a twin-engine Douglas DC-3-382 propliner, registration NC1946, operated by Transcontinental and Western Air (TWA) as a scheduled domestic passenger flight from New York, New York, to Burbank, California, in the United States, via several stopovers including Las Vegas, Nevada.[1] On January 16, 1942 at 19:20 PST, fifteen minutes after takeoff from Las Vegas Airport (now Nellis Air Force Base) bound for Burbank, the aircraft was destroyed when it crashed into a sheer cliff on Potosi Mountain, 32 miles (51 km) southwest of the airport, at an elevation of 7,770 ft (2,370 m) above sea level.[2] All 22 people on board, including movie star Carole Lombard, her mother, and three crew members, died in the crash. The Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB) investigated the accident and determined that the cause was a navigation error by the captain.[1]

Flight history

Transcontinental and Western Air (TWA) Flight 3 was flying a transcontinental route from New York City to Burbank, California, with multiple intermediate stops, including Indianapolis, St. Louis, Albuquerque, and Las Vegas.[1]

On the morning of January 16, 1942, at 4:00 local time, actress Carole Lombard, her mother, and her MGM press agent boarded Flight 3 in Indianapolis. Lombard, eager to meet her husband Clark Gable in Los Angeles, was returning from a successful war bond promotion tour in the Midwest, where she helped raise over $2 million.[3]

Upon arrival in Albuquerque, Lombard and her companions were asked to surrender their seats for the continuing flight segment to make room for fifteen United States Army Air Corps personnel flying to California. Lombard insisted that because of her war bond efforts she was also essential, and she convinced the station agent to let her group reboard the flight. Other passengers were removed instead, including violinist Joseph Szigeti.[3][4][5] The original flight crew was replaced by a new crew at Albuquerque. A refueling stop was planned at Winslow, Arizona, because of the higher passenger load and forecast headwinds. However, in the air the new captain decided to skip the Winslow stop and to proceed directly to Las Vegas.[1]

After a brief refueling stop at Las Vegas Airport (now Nellis Air Force Base) the plane took off on a clear, moonless[6] night for its final leg to Burbank. Fifteen minutes later, flying almost 7 mi (11 km) off course, it crashed into a near-vertical cliff on Potosi Mountain in the Spring Mountain range at 7,770 ft (2,370 m), about 80 ft (24 m) below the top of the cliff and 730 ft (220 m) below the summit, killing all aboard.[1]

Investigation

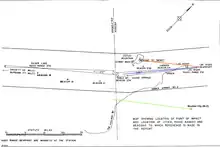

The accident was investigated by the Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB). Eyewitness and other evidence suggested that Flight 3 proceeded from its departure at Las Vegas along essentially a straight line, 10° right of the designated airway, into high terrain that rose above the flight altitude of 8,000 ft (2,400 m).[lower-alpha 1] This indicated to investigators that the crew was not using radio navigation to follow the airway (defined by the low frequency range), which would have provided them safe obstacle clearance, but was instead using a compass heading.[lower-alpha 2] Visibility was generally good, but since most airway light beacons had been turned off because of the ongoing Second World War they were not usable, although one important beacon was operating normally.[1][lower-alpha 3]

A key piece of evidence was the flight plan form, completed by the first officer in Albuquerque (but not signed by the captain, despite a company requirement to do so). On the form, the planned outbound magnetic course from Las Vegas was listed as 218°, which is close to the flight path actually flown by the crew to the crash point.[lower-alpha 4] Since this course, flown at 8,000 ft, is lower than the terrain in that direction (which rises to about 8,500 ft (2,600 m)), the board concluded that it was clearly an error. The board speculated that because both pilots had flown to Burbank much more frequently from Boulder City Airport than from Las Vegas,[lower-alpha 5] and that from Boulder City an outbound magnetic course of 218° would have been a reasonable choice to join the airway to Burbank, the crew likely inadvertently used the Boulder City outbound course instead of the appropriate Las Vegas course. Boulder City was not used as a refueling point on this trip as it had no runway lighting. To test its hypothesis, the CAB asked to review some other completed TWA flight plan forms for flights between Albuquerque and Las Vegas. The CAB members were surprised to discover a form from another flight that had also specified the same incorrect 218° outbound course from Las Vegas. TWA's chief pilot testified that the course written on that form was "obviously a mistake".[1]

The CAB issued a final report with the following probable cause statement:[1]

Upon the basis of the foregoing findings and of the entire record available at this time, we find that the probable cause of the accident to aircraft NC 1946 on January 16, 1942, was the failure of the captain after departure from Las Vegas to follow the proper course by making use of the navigational facilities available to him.

The CAB added the following contributing factors:[1]

- The use of an erroneous compass course

- Blackout of most of the beacons in the neighborhood of the accident made necessary by the war emergency

- Failure of the pilot to comply with TWA's directive of July 17, 1941, issued in accordance with a suggestion from the Administrator of Civil Aeronautics requesting pilots to confine their flight movements to the actual on-course signals

Conspiracy

In the book My Lunches with Orson, Orson Welles claims that he had been told by a security agent that Flight 3 was shot down by Nazi agents who knew of the route in advance.[7] He also claimed that news of the shooting was kept quiet to prevent vigilante action against Americans of German ancestry.[7] Neither claim was confirmed.[8]

See also

- List of accidents and incidents involving commercial aircraft

- 1949 Mexicana DC-3 crash that killed Mexican actress Blanca Estela Pavon

Notes

- ↑ According to the CAB report, the crash point was 6.7 mi (10.8 km) northwest of the center line of the airway, which was the southwest leg of the Las Vegas radio range.

- ↑ According to the CAB report, on July 15, 1941, the Civil Aeronautics Administration (CAA) sent TWA and other airlines an advisory notice "suggesting that pilots be instructed to confine their flight movements, day or night, contact or instrument, to the actual on-course signal of the radio ranges serving the airway involved". Two days later, TWA's Chief Pilot "incorporated this notice verbatim and requested pilots to be guided accordingly". The CAB cites this "failure of the [captain] to comply with TWA's directive" as a contributing cause.

- ↑ According to the CAB report, the one operating beacon in the area, referred to as "Arden beacon 24" (see diagram), was located 2.5 miles to the right of the airway. Had the crew used it as reference and passed to its left, the accident would have been avoided. The CAB speculated that the captain either ignored the beacon, or incorrectly assumed that it was centered on the airway, passing well to its right and into high terrain.

- ↑ The course flown to the crash point was 215° magnetic.

- ↑ Boulder City Airport (BLD) at that time, also called Bullock Airport, is now decommissioned. It was located just north of the modern Boulder City Municipal Airport (61B).

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "Final report of January 16, 1942 accident involving NC1946, Docket No. SA-58, File No. 119-42". Civil Aeronautics Board. July 16, 1942. Retrieved June 1, 2021. – PDF Alt URL

- ↑ "ASN accident record". ASN. Retrieved October 6, 2023.

- 1 2 "Tales of Vegas Past: The death of Carole Lombard". Las Vegas Mercury. March 6, 2003. Archived from the original on April 27, 2013. (archived)

- ↑ "CATASTROPHE: End of a Mission". Time. January 26, 1942. Archived from the original on December 11, 2008.

- ↑ "4 Gave Seats In Death Plane To Army Fliers". Greeley Daily Tribune. Greeley, Colorado. Associated Press. January 17, 1942. p. 1. Retrieved May 28, 2022 – via newspapers.com.

- ↑ Moon Phases Calendar for January, 1942, Calendar-12.com, retrieved February 1, 2018

- 1 2 Jaglom, Henry (2013), My Lunches With Orson, Metropolitan, pp. 63–64, ISBN 978-0-8050-9725-2

- ↑ Matzen, Robert (2017). Fireball: Carole Lombard and the Mystery of Flight 3. Pittsburgh: GoodKnight Books. p. 322. ISBN 978-0-9962740-9-8.

External links

- LostFlights – Aviation Archaeology site

- Location of crash site – on www.birdandhike.com

- Names of those aboard the aircraft via Google newspapers (scroll down to mid-page)

- Crash 75th anniversary via Las Vegas Review-Journal (also available archived)