| Part of a series on |

| Hindu scriptures and texts |

|---|

|

| Related Hindu texts |

The Taittirīya Upanishad (Devanagari: तैत्तिरीय उपनिषद्) is a Vedic era Sanskrit text, embedded as three chapters (adhyāya) of the Yajurveda. It is a mukhya (primary, principal) Upanishad, and likely composed about 6th century BC.[1]

The Taittirīya Upanishad is associated with the Taittirīya school of the Yajurveda, attributed to the pupils of sage Vaishampayana.[2] It lists as number 7 in the Muktika canon of 108 Upanishads.

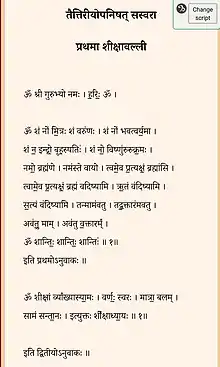

The Taittirīya Upanishad is the seventh, eighth and ninth chapters of Taittirīya Āraṇyaka, which are also called, respectively, the Śikṣāvallī, the Ānandavallī and the Bhṛguvallī.[3] This Upanishad is classified as part of the "black" Yajurveda, with the term "black" implying "the un-arranged, motley collection" of verses in Yajurveda, in contrast to the "white" (well arranged) Yajurveda where Brihadaranyaka Upanishad and Isha Upanishad are embedded.[3][4]

The Upanishad includes verses that are partly prayers and benedictions, partly instruction on phonetics and praxis, partly advice on ethics and morals given to graduating students from ancient Vedic gurukula-s (schools), partly a treatise on allegory, and partly philosophical instruction.[3]

Etymology

Taittiriya is a Sanskrit word that means "from Tittiri". The root of this name has been interpreted in two ways: "from Vedic sage Tittiri", who was the student of Yāska; or alternatively, it being a collection of verses from mythical students who became "partridges" (birds) in order to gain knowledge.[2] The later root of the title comes from the nature of Taittriya Upanishad which, like the rest of "dark or black Yajur Veda", is a motley, confusing collection of unrelated but individually meaningful verses.[2]

Each chapter of the Taittiriya Upanishad is called a Valli (वल्ली), which literally means a medicinal vine-like climbing plant that grows independently yet is attached to a main tree. Paul Deussen states that this symbolic terminology is apt and likely reflects the root and nature of the Taittiriya Upanishad, which too is largely independent of the liturgical Yajur Veda, and is attached to the main text.[3]

Chronology

The chronology of Taittiriya Upanishad, along with other Vedic era literature, is unclear.[5] All opinions rest on scanty evidence, assumptions about likely evolution of ideas, and on presumptions about which philosophy might have influenced which other Indian philosophies.[5][6]

Stephen Phillips[5] suggests that Taittiriya Upanishad was likely one of the early Upanishads, composed in the 1st half of 1st millennium BCE, after Brihadaranyaka, Chandogya, and Isha, but before Aitareya, Kaushitaki, Kena, Katha, Manduka, Prasna, Svetasvatara and Maitri Upanishads, as well as before the earliest Buddhist Pali and Jaina canons.[5]

Ranade[7] shares the view of Phillips in chronologically sequencing Taittiriya Upanishad with respect to other Upanishads. Paul Deussen[8] and Winternitz,[9] hold a similar view as that of Phillips, but place Taittiriya before Isha Upanishad, but after Brihadaranyaka Upanishad and Chandogya Upanishad.

According to a 1998 review by Patrick Olivelle, the Taittiriya Upanishad was composed in a pre-Buddhist period, possibly 6th to 5th century BCE.[10][11]

Structure

The Taittiriya Upanishad has three chapters: the Siksha Valli, the Ananda Valli and the Bhrigu Valli. The first chapter Siksha Valli includes twelve Anuvaka (lessons). The second chapter Ananda Valli, sometimes called Brahmananda Valli includes nine verses.[12] The third chapter Bhrigu Valli consists of ten verses.[13]

Some ancient and medieval Hindu scholars have classified the Taittiriya Upanishad differently, based on its structure. For example, Sâyana in his Bhasya (review and commentary) calls the Shiksha Valli (seventh chapter of the Aranyaka) as Sâmhitî-upanishad, and he prefers to treat the Ananda Valli and Bhrigu Valli (eighth and ninth Prapâthakas) as a separate Upanishad and calls it the Vārunya Upanishad.[12]

The Upanishad is one of the earliest known texts where an index was included at the end of each section, along with the main text, as a structural layout of the book. At the end of each Vallĩ in Taittiriya Upanishad manuscripts, there is an index of the Anuvakas which it contains. The index includes the initial words and final words of each Anuvaka, as well as the number of sections in that Anuvaka.[12] For example, the first and second Anuvakas of Shiksha Valli state in their indices that there are five sections each in them, the fourth Anuvaka asserts there are three sections and one paragraph in it, while the twelfth Anuvaka states it has one section and five paragraphs.[12] The Ananda Valli, according to the embedded index, state each chapter to be much larger than currently surviving texts. For example, the 1st Anuvaka lists pratika words in its index as brahmavid, idam, ayam, and states the number of sections to be twenty one. The 2nd Anuvaka asserts it has twenty six sections, the 3rd claims twenty two, the 4th has eighteen, the 5th has twenty two, the 6th Anuvaka asserts in its index that it has twenty eight sections, 7th claims sixteen, 8th states it includes fifty one sections, while the 9th asserts it has eleven. Similarly, the third Valli lists the pratika and anukramani in the index for each of the ten Anuvakas.[12]

Content

| Part of a series on |

| Hindu scriptures and texts |

|---|

|

| Related Hindu texts |

Shiksha Valli

The Siksha Valli chapter of Taittiriya Upanishad derives its name from Shiksha (Sanskrit: शिक्षा), which literally means "instruction, education".[14] The various lessons of this first chapter are related to education of students in ancient Vedic era of India, their initiation into a school and their responsibilities after graduation.[15] It mentions lifelong "pursuit of knowledge", includes hints of "Self-knowledge", but is largely independent of the second and third chapter of the Upanishad which discuss Atman and Self-knowledge. Paul Deussen states that the Shiksha Valli was likely the earliest chapter composed of this Upanishad, and the text grew over time with additional chapters.[16]

The Siksha Valli includes promises by students entering the Vedic school, an outline of basic course content, the nature of advanced courses and creative work from human relationships, ethical and social responsibilities of the teacher and the students, the role of breathing and proper pronunciation of Vedic literature, the duties and ethical precepts that the graduate must live up to post-graduation.[16][17]

A student's promise - First Anuvāka

The first anuvaka (lesson) of Taittiriya Upanishad starts with benedictions, wherein states Adi Shankara, major Vedic deities are proclaimed to be manifestations of Brahman (Cosmic Self, the constant Universal Principle, Unchanging Reality).[12][18] Along with the benedictions, the first anuvaka includes a prayer and promise that a student in Vedic age of India was supposed to recite. Along with benedictions to Vedic deities, the recitation stated,[19]

The right will I will speak,

and I will speak the true,

May That (Brahman) protect me; may That protect the teacher.

Om! Peace! Peace! Peace!— Taittiriya Upanishad, Translated by Swami Sharvananda[19]

Adi Shankara comments that the "Peace" phrase is repeated thrice, because there are three potential obstacles to the gain of Self-knowledge by a student: one's own behavior, other people's behavior, and the devas; these sources are exhorted to peace.[18]

Phonetics and the theory of connecting links - Second and Third Anuvāka

The second anuvaka highlights phonetics as an element of the Vedic instruction. The verse asserts that the student must master the principles of sound as it is created and as perceived, in terms of the structure of linguistics, vowels, consonants, balancing, accentuation (stress, meter), speaking correctly, and the connection of sounds in a word from articulatory and auditory perspectives.[20] Taittirĩya Upanishad emphasizes, in its later anuvakas, svādhyāya, a practice that served as the principal tool for the oral preservation of the Vedas in their original form for over two millennia. Svādhyāya as a part of student's instruction, involved understanding the linguistic principles coupled with recitation practice of Indian scriptures, which enabled the mastering of entire chapters and books with accurate pronunciation.[21] The ancient Indian studies of linguistics and recitation tradition, as mentioned in the second anuvaka of Taittiriya Upanishad, helped transmit and preserve the extensive Vedic literature from 2nd millennium BCE onwards, long before the methods of mass printing and book preservation were developed. Michael Witzel explains it as follows,[21]

The Vedic texts were orally composed and transmitted, without the use of script, in an unbroken line of transmission from teacher to student that was formalized early on. This ensured an impeccable textual transmission superior to the classical texts of other cultures; it is, in fact, something like a tape-recording.... Not just the actual words, but even the long-lost musical (tonal) accent (as in old Greek or in Japanese) has been preserved up to the present.[21]

The third anuvaka of Shiksha Valli asserts that everything in the universe is connected. In its theory of "connecting links", it states that letters are joined to form words and words are joined to express ideas, just like earth and heavens are forms causally joined by space through the medium of Vayu (air), and just like the fire and the sun are forms causally connected through lightning with the medium of clouds. It asserts that it is knowledge that connects the teacher and the student through the medium of exposition, while the child is the connecting link between the father and the mother through the medium of procreation.[20][22] Speech (expression) is the joining link between upper and lower jaw, and it is speech which connects people.[23]

A teacher's prayer - Fourth Anuvāka

The fourth anuvaka of Shiksha Valli is a prayer of the teacher,[24]

Students, may they come to me! Svaha! (liturgy exclamation)

Students, may they flock to me! Svaha!

Students, may they rush to me! Svaha!

Students, may they be controlled! Svaha!

Students, may they be tranquil! Svaha!

(...)

As waters flow down the slope;

And the months with the passing of the days;

So, O Creator, from everywhere,

May students come to me! Svaha!

You are a neighbor!

Shine on me!

Come to me!— Taittirĩya Upanishad, I.4.2[25]

The structure of the fourth anuvaka is unusual because it starts as a metered verse but slowly metamorphoses into a rhythmic Sanskrit prose. Additionally, the construction of the verse has creative elements that permits multiple translations.[24] The fourth anuvaka is also structured as a liturgical text, with many parts rhythmically ending in Svāhā, a term used when oblations are offered during yajna rituals.[26]

A theory of Oneness and holy exclamations - Fifth and Sixth Anuvāka

The fifth anuvaka declares that "Bhūr! Bhuvaḥ! Svar!" are three holy exclamations, then adds that Bhur is the breathing out, Bhuvah is the breathing in, while Svar is the intermediate step between those two. It also states that "Brahman is Atman (Self), and all deities and divinities are its limbs", that "Self-knowledge is the Eternal Principle", and the human beings who have this Oneness and Self-knowledge are served by the gods.[27]

The second part of the sixth anuvaka of Shiksha Valli asserts that the "Atman (Self) exists" and when an individual Self attains certain characteristics, it becomes one with Brahman (Cosmic Self, Eternal Reality). These characteristics are listed as follows in verse 1.6.2 :

He (the self) obtains sovereignty and becomes the lord of the mind, the lord of speech, the lord of sight, the lord of hearing, and the lord of perception. And thereafter, this is what he becomes — the Brahman whose body is space, whose self is truth (satya), whose pleasure ground is the lifebreath (prana), and whose joy is the mind; the Brahman who is completely tranquil and immortal. O Pracinayogya, venerate it in this manner!

— Taittirĩya Upanishad, I.6.2[28]

The sixth anuvaka ends with exhortation to meditate on this Oneness principle, during Pracina yogya (प्राचीन योग्य, ancient yoga),[29] making it one of the earliest mentions of the practice of meditative Yoga as existent in ancient India.[30]

Parallelism in knowledge and what is Om - Seventh and Eighth Anuvāka

The seventh anuvaka of Shiksha Valli is an unconnected lesson asserting that "everything in this whole world is fivefold" - sensory organs, human anatomy (skin, flesh, sinews, bones, marrow), breathing, energy (fire, wind, sun, moon, stars), space (earth, aerial space, heavens, poles, intermediate poles).[31] This section does not contextually fit with the sixth or eighth lesson. It is the concluding words of the seventh anuvaka that makes it relevant to the Taittiriya Upanishad, by asserting the idea of fractal nature of existence where the same hidden principles of nature and reality are present in macro and micro forms, there is parallelism in all knowledge. Paul Deussen states that these concluding words of the seventh lesson of Shiksha Valli assert, "there is parallelism between man and the world, microcosm and macrocosm, and he who understands this idea of parallelism becomes there through the macrocosm itself".[32]

What is ॐ?

The eighth anuvaka, similarly, is another seemingly unconnected lesson. It includes an exposition of the syllable word Om (ॐ, sometimes spelled Aum), stating that this word is inner part of the word Brahman, it signifies the Brahman, it is this whole world states the eight lesson in the first section of the Taittiriya Upanishad. The verse asserts that this syllable word is used often and for diverse purposes, to remind and celebrate that Brahman. It lists the diverse uses of Om in ancient India, at invocations, at Agnidhra, in songs of the Samans, in prayers, in Sastras, during sacrifices, during rituals, during meditation, and during recitation of the Vedas.[31][33]

Ethical duties of human beings - Ninth Anuvāka

The ninth anuvaka of Shiksha Valli is a rhythmic recitation of ethical duties of all human beings, where svādhyāya is the "perusal of oneself" (study yourself), and the pravacana (प्रवचन, exposition and discussion of Vedas)[34] is emphasized.[35][36]

ऋतं च स्वाध्यायप्रवचने च । सत्यं च स्वाध्यायप्रवचने च । तपश्च स्वाध्यायप्रवचने च । दमश्च स्वाध्यायप्रवचने च । शमश्च स्वाध्यायप्रवचने च । अग्नयश्च स्वाध्यायप्रवचने च । अग्निहोत्रं च स्वाध्यायप्रवचने च । अतिथयश्च स्वाध्यायप्रवचने च । मानुषं च स्वाध्यायप्रवचने च । प्रजा च स्वाध्यायप्रवचने च । प्रजनश्च स्वाध्यायप्रवचने च । प्रजातिश्च स्वाध्यायप्रवचने च । सत्यमिति सत्यवचा राथीतरः । तप इति तपोनित्यः पौरुशिष्टिः । स्वाध्यायप्रवचने एवेति नाको मौद्गल्यः । तद्धि तपस्तद्धि तपः ॥[37]

Justice with svādhyāya and pravacana (must be practiced),

Truth with svādhyāya and pravacana,

Tapas with svādhyāya and pravacana,

Damah with svādhyāya and pravacana,

Tranquility and forgiveness with svādhyāya and pravacana,

Fire rituals with svādhyāya and pravacana,

Oblations during fire rituals with svādhyāya and pravacana,

Hospitality to one's guest to the best of one's ability with svādhyāya and pravacana,

Kind affability with all human beings with svādhyāya and pravacana,

Procreation with svādhyāya and pravacana,

Sexual intercourse with svādhyāya and pravacana,

Raising children to the best of one's ability with svādhyāya and pravacana,

Truthfulness opines (sage) Satyavacā Rāthītara,

Tapas opines (sage) Taponitya Pauruśiṣṭi,

Svādhyāya and pravacana opines (sage) Naka Maudgalya

– because that is tapas, that is tapas.

Tenth Anuvāka

The tenth anuvaka is obscure, unrelated lesson, likely a corrupted or incomplete surviving version of the original, according to Paul Deussen. It is rhythmic with Mahabrihati Yavamadhya meter, a mathematical "8+8+12+8+8" structure.[38]

Max Muller translates it as an affirmation of one's Self as a capable, empowered blissful being.[39] The tenth anuvaka asserts, "I am he who shakes the tree. I am glorious like the top of a mountain. I, whose pure light (of knowledge) has risen, am that which is truly immortal, as it resides in the sun. I (Self) am the treasure, wise, immortal, imperishable. This is the teaching of the Veda, by sage Trisanku."[39] Shankara states[40] that the tree is a metaphor for the empirical world, which is shaken by knowledge and realization of Atman-Brahman (Self, eternal reality and hidden invisible principles).

Convocation address to graduating students, living ethically - Eleventh Anuvāka

The eleventh anuvaka of Shiksha Valli is a list of golden rules which the Vedic era teacher imparted to the graduating students as the ethical way of life.[41][42] The verses ask the graduate to take care of themselves and pursue Dharma, Artha and Kama to the best of their abilities. Parts of the verses in section 1.11.1, for example, state[41]

Never err from Truth,

Never err from Dharma,

Never neglect your well-being,

Never neglect your health,

Never neglect your prosperity,

Never neglect Svādhyāya (study of oneself) and Pravacana (exposition of Vedas).

The eleventh anuvaka of Shiksha Valli list behavioral guidelines for the graduating students from a gurukula,[43]

मातृदेवो भव । पितृदेवो भव ।

आचार्यदेवो भव । अतिथिदेवो भव ।

यान्यनवद्यानि कर्माणि तानि सेवितव्यानि । नो इतराणि ।

यान्यस्माकँ सुचरितानि तानि त्वयोपास्यानि । नो इतराणि ॥ २ ॥

Be one to whom a mother is as god, be one to whom a father is as god,

Be one to whom an Acharya (spiritual guide, scholars you learn from) is as god, be one to whom a guest is as god.[43]

Let your actions be uncensurable, none else.

Those acts that you consider good when done to you, do those to others, none else.

The third section of the eleventh anuvaka lists charity and giving, with faith, sympathy, modesty and cheerfulness, as ethical precept for the graduating students.[42]

Scholars have debated whether the guidelines to morality in this Taittiriya Upanishad anuvaka are consistent with the "Know yourself" spirit of the Upanishads. Adi Shankara states that they are, because there is a difference between theory and practice, learning the need for Self-knowledge and the ethics that results from such Self-knowledge is not same as living practice of the same. Ethical living accelerates Self-knowledge in the graduate.[41][42]

Graduating student's acknowledgment - Twelfth Anuvāka

The last anuvaka (lesson) of Taittiriya Upanishad, just like the first anuvaka, starts with benedictions, wherein Vedic deities are once again proclaimed to be manifestations of Brahman (Cosmic Self, Unchanging Reality).[12][44] Along with the benedictions, the last anuvaka includes an acknowledgment that mirrors the promise in first anuvaka,[45]

I have proclaimed you,

And you alone as the visible Brahman!

I have proclaimed you as the right!

I have proclaimed you as the true!

It has helped me.

It has helped the teacher.

Yes, it has helped me.

And it has helped the teacher.

Om, Peace! Peace! Peace!— Taittirĩya Upanishad, I.12.1, Translated by Patrick Olivelle[46]

Ananda Valli

ॐ

सह नाववतु ।

सह नौ भुनक्तु । सह वीर्यं करवावहै ।

तेजस्वि नावधीतमस्तु मा विद्विषावहै ।

ॐ शान्तिः शान्तिः शान्तिः ॥

Om!

May it (Brahman) protect us both (teacher and student)!

May we both enjoy knowledge! May we learn together!

May our study be brilliant! May we never quarrel!

Om! Peace! peace! peace!

—Taittiriya Upanishad, Anandavalli Invocation[47]

The second chapter of Taittiriya Upanishad, namely Ananda Valli and sometimes called Brahmananda Valli, focuses like other ancient Upanishads on the theme of Atman (Self). It asserts that "Atman exists", it is Brahman, and realizing it is the highest, empowering, liberating knowledge.[48] The Ananda Valli asserts that knowing one's Self is the path to freedom from all concerns, fears and to a positive state of blissful living.[48]

The Ananda Valli is remarkable for its Kosha (Sanskrit: कोष) theory (or Layered Maya theory), expressing that man reaches his highest potential and understands the deepest knowledge by a process of learning the right and unlearning the wrong. Real deeper knowledge is hidden in layers of superficial knowledge, but superficial knowledge is easier and simplistic. The Ananda Valli classifies these as concentric layers (sheaths) of knowledge-seeking.[49] The outermost layer it calls Annamaya which envelops and hides Pranamaya, which in turn envelops Manomaya, inside which is Vijnanamaya, and finally the Anandamaya which the Upanishad states is the innermost, deepest layer.[48][50][51]

The Ananda Valli asserts that Self-knowledge is "not" attainable by cultic worship of God or gods motivated by egoistic cravings and desires (Manomaya).[48] Vijnanamaya or one with segregated knowledge experiences the deeper state of existence but it too is insufficient. The complete, unified and blissful state of Self-knowledge is, states Ananda Valli, that where one becomes one with all reality, there is no separation between object and subject, I and we, Atman and Brahman. Realization of Atman is a deep state of absorption, oneness, communion.[48]

The Ananda valli is one of the earliest known theories in history on the nature of man and knowledge, and resembles but pre-dates the Hellenistic Hermetic and Neoplatonic theories recorded in different forms about a millennium later, such as those expressed in the Corpus Hermetica.[51][52]

Annamaya - First and Second Anuvāka

The first anuvaka commences by stating the premise and a summary of the entire Ananda Valli.[48]

ब्रह्मविदाप्नोति परम् । तदेषाऽभ्युक्ता । सत्यं ज्ञानमनन्तं ब्रह्म ।

One who knows Brahman, reaches the highest. Satya (reality, truth) is Brahman, Jnana (knowledge) is Brahman, Ananta (infinite) is Brahman.

Paul Deussen notes that the word Ananta in verse 1 may be vulgate, and a related term Ananda, similarly pronounced, is more consistent with the teachings of other Upanishads of Hinduism, particularly one of its central premise of Atman being sat-chit-ananda. In Deussen's review and translation, instead of "Brahman is infinite", an alternate expression would read "Brahman is bliss".[48]

The second anuvaka of Ananda Valli then proceeds to explain the first layer of man's nature and knowledge-seeking to be about "material man and material nature", with the metaphor of food.[54] The Taittiriya Upanishad asserts that both "material man and material nature" are caused by Brahman, are manifestations of Brahman, are Brahman, but only the outermost shell or sheath of existence.[54] The verse offers relational connection between natural elements, asserting that everything is food to something else in universe at the empirical level of existence, either at a given time, or over time.[54] All creatures are born out of this "food provided by nature and food provided by life with time". All creatures grow due to food, and thus are interdependent. All creatures, upon their death, become food in this food-chain, states Ananda Valli's second verse. Learning, knowing and understanding this "food chain" material nature of existence and the interdependence is the first essential, yet outermost incomplete knowledge.[54][55]

Pranamaya - Third Anuvāka

The second inner level of nature and knowledge-seeking is about life-force, asserts Ananda Valli's third anuvaka.[54] This life-force is identified by and dependent on breathing. Gods breathe, human beings breathe, animals breathe, as do all beings that exist. Life-force is more than material universe, it includes animating processes inside the being, particularly breathing, and this layer of nature and knowledge is Pranamaya kosha.[54]

Manomaya - Fourth Anuvāka

The next inner, deeper layer of nature and knowledge-seeking relates to Manas (mind, thought, will, wish), or Manomaya kosha.[54] Manas, asserts the fourth anuvaka of Ananda Valli, exists only in individual forms of beings. It is characterized by the power to will, the ability to wish, and the striving for prosperity through actions on the empirical nature, knowledge and beings.[56] The verse of fourth anuvaka add that this knowledge is essential yet incomplete, that it the knowledge of Brahman that truly liberates, and one who knows Atman-Brahman "dreads nothing, now and never" and "lives contently, in bliss".[56]

Vijñãnamaya - Fifth Anuvāka

The fifth anuvaka of Ananda Valli states that the "manomaya kosha" (thought, will, wish) envelops a deeper more profound layer of existence, which is the "vijnana-maya kosha" (knowledge, ethics, reason). This is the realm of knowledge observed in all human beings. The vijnana-maya is characterized by faith, justice, truth, yoga and mahas (power to perceive and reason). The individual who is aware of vijnana-maya, asserts the verses of Ananda Valli, offers knowledge as the work to others.[57]

Anandamaya - Sixth, Seventh, Eighth and Ninth Anuvāka

The sixth, seventh and eighth anuvaka of Ananda Valli states that the "vijnanamaya kosha" (knowledge, ethics, reason) envelops the deepest, hidden layer of existence, which is the "ananda-maya kosha" (bliss, tranquility, contentness). This is the inner most is the realm of Atman-Brahman (Self, spirituality).[58] The ananda-maya is characterized by love, joy, cheerfulness, bliss and Brahman. The individuals who are aware of ananda-maya, assert the sixth to eighth verses of Ananda Valli, are those who simultaneously realize the empirical and the spiritual, the conscious and unconscious, the changing and the eternal, the time and the timeless.[58]

These last anuvakas of the second Valli of Tattiriya Upanishad assert that he who has Self-knowledge is well constituted, he realizes the essence, he is full of bliss. He exists in peace within and without, his is a state of calm joy irrespective of circumstances, he is One with everything and everyone. He fears nothing, he fears no one, he lives his true nature, he is free from pride, he is free from guilt, he is beyond good and evil, he is free from craving desires and thus all the universe is in him and is his.[58] His blissful being is Atman-Brahman, and Atman-Brahman is the bliss that is he.

Bhṛgu Vallī

The third Valli of Tattiriya Upanishad repeats the ideas of Ananda Valli, through a story about sage Bhrigu. The chapter is also similar in its themes and focus to those found in chapter 3 of Kausitaki Upanishad and chapter 8 of Chandogya Upanishad.[59] The Bhrigu Valli's theme is the exposition of the concept of Atman-Brahman (Self) and what it means to be a self-realized, free, liberated human being.[60]

The first six anuvakas of Bhrigu Valli are called Bhargavi Varuni Vidya, which means "the knowledge Bhrigu got from (his father) Varuni". It is in these anuvakas that sage Varuni advises Bhrigu with one of the oft-cited definition of Brahman, as "that from which beings originate, through which they live, and in which they re-enter after death, explore that because that is Brahman".[59] This thematic, all encompassing, eternal nature of reality and existence develops as the basis for Bhrigu's emphasis on introspection and inwardization, to help peel off the outer husks of knowledge, in order to reach and realize the innermost kernel of spiritual Self-knowledge.[59]

The last four of the ten anuvakas of Bhrigu Valli build on this foundation, but once again like Ananda Valli, use the metaphor of "food" as in Ananda Valli.[59] As with Ananda Valli, in Bhrigu Valli, everything and everyone is asserted to be connected and deeply inter-related to everything and everyone else, by being food (of energy, of material, of knowledge). "Food is founded on food", asserts verse 3.9 of Taittiriya Upanishad, which then illustrates the idea with the specific example "earth is founded on (food for) space, and space is founded on (food for) earth".[59]

Brahman is bliss for clearly,

it is from bliss that these beings are born;

through bliss, once born, do they live;

& into bliss do they pass upon death— Sixth Anuvāka, Bhrigu Valli, Taittiriya Upanishad 3.6, Translated by Patrick Olivelle[61]

After discussing the nature of Brahman, the Bhrigu Valli chapter of Taittiriya Upanishad recommends the following maxims and vows:[12][59][62]

- "Never scorn food", which metaphorically means "never scorn anything or anyone".

- "Increase food", which metaphorically means "increase prosperity of everyone and everything".

- "Refuse no guest to your house, and share food with everyone including strangers", which metaphorically means "compassionately help everyone, sharing plentiful prosperity and knowledge".

The Taittiriya Upanishad closes with the following advaita declaration,[59][60]

Ha u! Ha u! Ha u!

I am food! I am food! I am food!

I eat food! I eat food! I eat food!

I set the rhythm! I set the rhythm! I set the rhythm!

I am the first-born of Ṛta,[63]

Born before the gods,

in the navel of the immortal.

The one who gives me

will indeed eat me.

I am food!

I eat him who eats the food!

I have conquered the whole universe!

I am like the light in the heavens (firmament)!

(And so will) anyone who knows this, that is the hidden teaching (upanishad)— Bhrigu Valli, Taittiriya Upanishad 3.10[64]

Translations

A number of commentaries were published on the Taittiriya Upanishad in Sanskrit and Indian languages through the years, including popular ones by Shankara, Sayanana and Ramanuja. Though, the first European translations of the work began to appear in 1805, up to the early 1900s some information on vedas were known to Europeans before. They began to appear in English, German and French, primarily by Max Muller, Griffith, Muir, and Wilson, all of whom were either western academics based in Europe or in colonial India.[65] The Taittiriya Upanishad was first translated in Non Indian languages Jacqueline Hirst, in her analysis of Adi Shankara's works, states that Taittiriya Upanishad Bhasya provides one of his key exegesis. Shankara presents Knowledge and Truth as different, non-superimposable but interrelated. Knowledge can be right or wrong, correct or incorrect, a distinction that principles of Truth and Truthfulness help distinguish. Truth cleanses knowledge, helping man understand the nature of empirical truths and hidden truths (invisible laws and principles, Self). Together states Shankara in his Taittiriya Upanishad Bhasya, Knowledge and Truth point to Oneness of all, Brahman as nothing other than Self in every human being.[66]

Paul Horsch, in his review of the historical development of Dharma concept and ethics in Indian philosophies, includes Taittiriya Upanishad as among the ancient influential texts.[67] Kirkwood makes a similar observation.[68]

Bhatta states that Taittiriya Upanishad is one of earliest expositions of education system in ancient Indian culture.[69]

Paul Deussen, in his preface to Taittiriya Upanishad's translation, states that Ananda Valli chapter of Taittiriya Upanishad is "one of the most beautiful evidences of the ancient Indian's deep absorption in the mystery of nature and of the inmost part of the human being".[70]

The Taittiriya Upanishad has been translated into a number of Indian languages as well, by a large number of scholars including Dayanand Saraswati, Bhandarkar, and in more recent years, by organisations such as the Chinmayananda mission.[71]

See also

References

- ↑ Angot, Michel. (2007) Taittiriya-Upanisad avec le commentaire de Samkara, p.7. College de France, Paris. ISBN 2-86803-074-2

- 1 2 3 A Weber, History of Indian Literature, p. 87, at Google Books, Trubner & Co, pages 87-91

- 1 2 3 4 Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 217-219

- ↑ Taittiriya Upanishad SS Sastri (Translator), The Aitereya and Taittiriya Upanishad, pages 57-192

- 1 2 3 4 Stephen Phillips (2009), Yoga, Karma, and Rebirth: A Brief History and Philosophy, Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0231144858, Chapter 1

- ↑ Patrick Olivelle (1996), The Early Upanishads: Annotated Text & Translation, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195124354, Introduction Chapter

- ↑ RD Ranade, A Constructive Survey of Upanishadic Philosophy, Chapter 1, pages 13-18

- ↑ Paul Deussen, The Philosophy of the Upanishads, pages 22-26

- ↑ M Winternitz (2010), History of Indian Literature, Vol 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120802643

- ↑ Patrick Olivelle (1998). The Early Upanishads: Annotated Text and Translation. Oxford University Press. pp. 12–13. ISBN 978-0-19-512435-4.

- ↑ Stephen Phillips (2009). Yoga, Karma, and Rebirth: A Brief History and Philosophy. Columbia University Press. pp. 28–30. ISBN 978-0-231-14485-8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Max Muller, The Sacred Books of the East, Volume 15, Oxford University Press, Chapter 3: Taittiriya Upanishad, Archived Online

- ↑ Original: Taittiriya Upanishad (Sanskrit);

English Translation: Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 220-246 - ↑ zikSA Sanskrit English Dictionary, Cologne University, Germany

- ↑ CP Bhatta (2009), Holistic Personality Development through Education: Ancient Indian Cultural Experiences, Journal of Human Values, vol. 15, no. 1, pages 49-59

- 1 2 Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 220-231

- ↑ Aitareya and Taittiriya Upanishads with Shankara Bhashya SA Sastri (Translator), pages 56-192

- 1 2 Aitareya and Taittiriya Upanishads with Shankara Bhashya SA Sastri (Translator), page 62

- 1 2 Swami Sharvananda, Taittiriya Upanishad, Ramakrishna Math, Chennai, ISBN 81-7823-050-X, page 6-7

- 1 2 Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 222-223

- 1 2 3 Flood, Gavin, ed. (2003). The Blackwell Companion to Hinduism. Blackwell Publishing Ltd. pp. 68–70. ISBN 1-4051-3251-5.

- ↑ Taittiriya Upanishad SS Sastri (Translator), The Aitereya and Taittiriya Upanishad, pages 65-67

- ↑ Max Muller, Taittiriya Upanishad in The Sacred Books of the East, Volume 15, Oxford University Press

- 1 2 Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 223-224

- ↑ Translation by Patrick Olivelle, http://www.ahandfulofleaves.org/documents/the%20early%20upanisads%20annotated%20text%20and%20translation_olivelle.pdf

- ↑ Taittiriya Upanishad SS Sastri (Translator), The Aitereya and Taittiriya Upanishad, pages 69-71

- ↑ Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, page 225

- ↑ Translation by Patrick Olivelle, http://www.ahandfulofleaves.org/documents/the%20early%20upanisads%20annotated%20text%20and%20translation_olivelle.pdf

- ↑ Sanskrit original: इति प्राचीनयोग्योपास्स्व; Wikisource

- ↑ Taittiriya Upanishad - Shiksha Valli, Chapter VI SS Sastri (Translator), The Aitereya and Taittiriya Upanishad, page 77

- 1 2 Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, page 227

- ↑ Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, page 226

- ↑ Taittiriya Upanishad - Shiksha Valli, Chapter VIII SS Sastri (Translator), The Aitereya and Taittiriya Upanishad, pages 82-84

- ↑ pravacana Sanskrit English Dictionary, Cologne University, Germany

- 1 2 Taittiriya Upanishad SS Sastri (Translator), The Aitereya and Taittiriya Upanishad, pages 84-86

- 1 2 Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, page 228

- ↑ तैत्तिरीयोपनिषद् - शीक्षावल्ली ॥ नवमोऽनुवाकः ॥ (Wikisource)

- ↑ Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 228-229

- 1 2 Max Muller, The Sacred Books of the East, Volume 15, Oxford University Press, Chapter 3: Taittiriya Upanishad, see Siksha Valli - Tenth Anuvaka

- ↑ Taittiriya Upanishad SS Sastri (Translator), The Aitereya and Taittiriya Upanishad, pages 86-89

- 1 2 3 4 5 Taittiriya Upanishad SS Sastri (Translator), The Aitereya and Taittiriya Upanishad, pages 89-92

- 1 2 3 4 5 Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 229-231

- 1 2 Taittiriya Upanishad Thirteen Principle Upanishads, Robert Hume (Translator), pages 281-282

- ↑ Aitareya and Taittiriya Upanishads with Shankara Bhashya SA Sastri (Translator), pages 94-96

- ↑ Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, page 231-232

- ↑ Article title

- ↑

- Original Sanskrit: Taittiriya Upanishad 2.1.1 Wikisource;

- Translation 1: Taittiriya Upanishad SS Sastri (Translator), The Aitereya and Taittiriya Upanishad, pages 104-105

- Translation 2: Max Muller, The Sacred Books of the East, Volume 15, Oxford University Press, Chapter 3: Taittiriya Upanishad, see Ananda Valli Invocation

- ↑ PT Raju, The Concept of the Spiritual in Indian Thought, Philosophy East and West, Vol. 4, No. 3, pages 195-213

- ↑ S Mukerjee (2011), Indian Management Philosophy, in The Palgrave Handbook of Spirituality and Business (Editors: Luk Bouckaert and Laszlo Zsolnai), Palgrave Macmillan, ISBN 978-0230238312, pages 82-83

- 1 2 Eliot Deutsch (1980), Advaita Vedanta: A Philosophical Reconstruction, University of Hawaii Press, pages 56-60

- ↑ The Corpus Hermeticum and Hermetic Tradition GRS Mead (Translator); also see The Hymns of Hermes in the same source.

- ↑ Taittiriya Upanishad Thirteen Principle Upanishads, Robert Hume (Translator), pages 283-284

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 234-236

- ↑ Taittiriya Upanishad SS Sastri (Translator), The Aitereya and Taittiriya Upanishad, pages 104-112

- 1 2 Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 233-237

- ↑ Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, page 237

- 1 2 3 Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 237-240

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 241-246

- 1 2 Taittiriya Upanishad AM Sastri (Translator), GTA Printing Works, Mysore, pages 699-791

- ↑ Article title

- ↑ Taittiriya Upanishad SS Sastri (Translator), The Aitereya and Taittiriya Upanishad, pages 170-192

- ↑ right, just, natural order, connecting principle

- ↑ Patrick Olivelle, http://www.ahandfulofleaves.org/documents/the%20early%20upanisads%20annotated%20text%20and%20translation_olivelle.pdf

- ↑ Griffith, Ralph (1 November 1896). The hymns of the Rig Veda (2 ed.). Kotagiri, Nilgiris.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Jacqueline Suthren Hirst (2004), Images of Śaṃkara: Understanding the Other, International Journal of Hindu Studies, Vol. 8, No. 1/3 (Jan., 2004), pages 157-181

- ↑ Paul Horsch, From Creation Myth to World Law: The early history of Dharma, Translated by Jarrod L. Whitaker (2004), Journal of Indian Philosophy, vol. 32, pages 423–448

- ↑ William G. Kirkwood (1989), Truthfulness as a standard for speech in ancient India, Southern Communication Journal, Volume 54, Issue 3, pages 213-234

- ↑ CP Bhatta (2009), Holistic Personality Development through Education - Ancient Indian Cultural Experiences, Journal of Human Values, January/June 2009, vol. 15, no. 1, pages 49-59

- ↑ Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, page 232

- ↑ Sarma, RVSN. "Purusha Suktam - the vedic hymn" (PDF). Retrieved 18 September 2018.

Further reading

- Outlines Of Indian Philosophy by M.Hiriyanna. Motilal Banarasidas Publishers.

- Kannada Translation of Taittireeya Upanishad by Swami Adidevananda Ramakrishna Mission Publishers.

External links

- The Taittiriya Upanishad with the commentaries of Śaṅkarāchārya, Sureśvarāchārya and Sāyaṇa (Vidyāraṇya) Translated by AM Sastry (proofread edition with proper unicode diacritics and a glossary); originally scanned at archive.org)

- Taittiriya Upanishad, Translated by Swami Sharvananda with the original text in Devanagari, transliteration of each shloka, and word-for-word English rendering followed by a running translation and notes based on Shankaracharya's commentary. ISBN 81-7823-050-X

- Taittiriya Upanishad, Multiple translations (Johnston, Nikhilānanda, Gambhirananda)

- Taittiriya Upanishad, Sanskrit manuscript

- Taittiriya Upanishad, Sanskrit manuscript with Vedic accents

- Taittiriya Upanishad Archived 13 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine Vision of Advaita Vedanta in Taittiriya Upanishad