| Tamanowas Rock | |

|---|---|

| Chimacum Rock, Tamanous Rock | |

| |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 440 ft (130 m) |

| Prominence | 150 ft (46 m)[1] |

| Coordinates | 48°01′19″N 122°47′36″W / 48.02208°N 122.79339°W |

| Geography | |

| Location | Jefferson County, Washington, US |

| Parent range | Near Olympic Mountains |

| Topo map | USGS Port Townsend South, WA |

| Geology | |

| Mountain type | Batholith |

| Tamanowas Rock Sanctuary | |

|---|---|

Location in the United States | |

| Nearest city | Chimacum, Washington |

| Coordinates | 48°01′19″N 122°47′36″W / 48.02208°N 122.79339°W |

| Area | 84.4 acres (34.2 ha)[2][3] |

| Established | 1990s–December 21, 2012[4] |

| Governing body | Jamestown S'Klallam Tribe |

Tamanowas Rock (Clallam: t̕əménəwəs) (also spelled Tamanous[5]), also called Chimacum Rock, is a 150-foot (46 m) high rock with caves and crevices that lies in a forest adjacent to Anderson Lake State Park, near Port Townsend, Washington.[1][6]: 169 It is a sacred site to the Coast Salish peoples of the Pacific Northwest and a pilgrimage site.[7] The rock was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2015.[8]

History

Tamanowas Rock is said to have first been used 10,000 years ago by the Chimakum (or Chemacum) people,leading to its alternate name "Chimacum Rock", whose name is also found in other local geographic features.[3] In accordance with legend, it may have been used as a refuge from the tsunami caused by the 1700 Cascadia earthquake, and earlier as a lookout for hunting now-extinct mastodon.[9] "Tamanowas" means "spirit power" in the Klallam language.[4]

Preservation

The site is either a registered archaeological site, or nominated to become one with the Washington State Department of Archaeology.[10]

In 2013, the rock was purchased with 62 acres (25 ha) of surrounding land by the Jamestown S'Klallam Tribe for preservation, at the end of a series of loans and purchases by organizations including Washington State Parks, Bullitt Foundation and Jefferson Land Trust, that started in 2009.[5][6] The land was added to an existing 22-acre purchase by the tribe. Prior to this, it was a rock climbing site,[11][12] a practice which was ended when the S'Klallam Tribe took ownership.[1][7][13][4]

Desecration

In 2014, the rock was desecrated with graffiti, gaining national and international attention.[14][15][16][17][18][19]

Geology

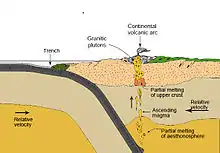

The mineral composition is Eocene subaerial adakitic lava and lava breccia.[20] Dikes of similar composition exist in the Blue Hills near Bremerton 60 km away, both thought to be created by subduction of the Kula-Farallon Ridge beneath North America. They may be related by being part of a magmatic arc , they may be two isolated volcanic centers, or they may have been created at a single center and displaced along a fault (see Puget Sound faults).[21][22]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Tamanowas Rock site on Olympic Peninsula purchased by Jamestown S'Kallam tribe, Associated Press, January 6, 2013 – via The Oregonian

- ↑ "Listing of acreage – December 31, 2011" (XLSX). Land Resource Division, National Park Service. Retrieved May 13, 2012. (National Park Service Acreage Reports)

- 1 2 Tamanowas Rock Sanctuary, Jefferson Land Trust, archived from the original on 2015-07-26, retrieved 2015-06-22

- 1 2 3 "Jamestown S'Klallam Tribe buys sacred site of Tamanowas Rock", Peninsula Daily News, January 6, 2013

- 1 2 Barney Burke (December 17, 2009), "Tamanous Rock, forever: Tamanous Rock, sacred to S'Klallams, preserved from development", Port Townsend Leader

- 1 2 Middleton, Beth Rose (2011). Trust in the Land: New Directions in Tribal Conservation. University of Arizona Press. pp. 169–172. ISBN 9780816502295.

- 1 2 2013 Annual Report (PDF), Jamestown S'Klallam Tribe, 2014, p. 27

- ↑ National Park Service (August 14, 2015), Weekly List of Actions Taken on Properties: 8/03/15 through 8/07/15, retrieved August 14, 2015.

- ↑ Dan McShane (January 7, 2013), "Tamanowas Rock Update", Reading the Washington Landscape (blog)

- ↑ Washington State Advisory Council on Historic Preservation's nominations, Washington State Department of Archaeology, archived from the original on 2015-06-23, retrieved 2015-06-22

- ↑ Jeff Chew (April 18, 2010), "View from Tamanowas' top: Conservation groups fret over future of Jefferson monolith", Peninsula Daily News

- ↑ Dan McShane (October 29, 2010), "Adakite and Tamanowas Rock (Chimacum Rock)", Reading the Washington Landscape (blog)

- ↑ Blumhagen, Stephanie (2013). Collaboration for Protection of a Sacred Site: A Case Study on Tamanowas Rock (PDF) (Master of Environmental Studies thesis). The Evergreen State College.

- ↑ "Affectionate Graffiti Mars Sacred Indian Site", The New York Times, August 3, 2014

- ↑ Lover's Graffiti Scrawled Across Sacred Rock: A vandal daubed the huge letters on a spiritual rock that has been used for millennia by Salish Native Americans, Sky News, 5 August 2014

- ↑ Ancient Native American site desecrated, Associated Press, August 4, 2014 – via CBS News

- ↑ Graffiti mars sacred Indian site in US, Press Trust of India, 4 August 2014 – via Zee News

- ↑ "Graffiti mars sacred Indian site in US", New Zealand Herald, August 3, 2014

- ↑ "Tribe offers reward for info on Tamanowas Rock vandalism", Peninsula Daily News, August 9, 2014

- ↑ Dave Tucker (November 8, 2010), "Tamanowas Rock, Chimacum, Olympic Peninsula", Northwest Geology Field Trips (blog)

- ↑ Hahn, M., A. Graettinger, J. Gustafson, Caroline J. Ponzini, et al. 2004. "Eocene pyroclastic deposits at Chimacum, Washington; adakite magmatism in the Cascadia Forearc." Abstracts With Programs - Geological Society Of America 36(4; 4): 69-69. abstract

- ↑ Tepper, J.; Clark, K.; Asmerom, Y.; McIntosh, W. (December 2002), "Eocene Adakites Associated With Initiation of Cascade Subduction, Puget Lowlands, WA", American Geophysical Union, Fall Meeting 2002, abstract #V11A-1381, vol. 2002, Bibcode:2002AGUFM.V11A1381T, 2002AGUFM.V11A1381T