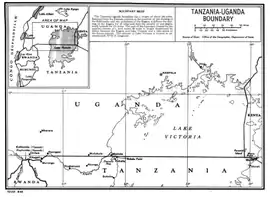

The Tanganyika laughter epidemic of 1962 was an outbreak of mass hysteria—or mass psychogenic illness (MPI)—rumored to have occurred in or near the village of Kashasha on the western coast of Lake Victoria in Tanganyika (which, once united with Zanzibar, became the modern nation of Tanzania) near the border with Uganda.[1]

History

The laughter epidemic began on January 30, 1962, at a mission-run boarding school for girls in Kashasha. It started with three girls and spread throughout the school, affecting 95 of the 159 pupils, aged 12–18.[2][3] Symptoms lasted from a few hours to 16 days, averaging around 7 days.[4] The teaching staff were unaffected and reported that students were unable to concentrate on their lessons. The first outbreak in Kashasha lasted roughly 48 days. The school was forced to close on March 18, 1962.[5] When it reopened on May 21, a second phase of the outbreak affected an additional 57 pupils. The all-girl boarding school reclosed at the end of June.[4][3]

The epidemic spread to Nshamba of the Muleba District, a village 55 miles west of Bukoba, where several of the girls lived.[5] In April and May 1962, 217 mostly young villagers had laughing attacks over the course of 34 days. The Kashasha school was sued for allowing the children and their parents to transmit it to the surrounding area. In June, the laughing epidemic spread to Ramashenye girls' middle school, affecting 48 girls.[2] Additional schools and the Kanyangereka village were also affected to some degree.[5] The phenomenon died off 18 months after it started. All areas affected were within a 100-mile radius of Bukoba.[4] In all, 14 schools were shut down and 1000 people were affected.[6]

Causes and symptoms

Symptoms[7] of the Tanganyika 'laughter epidemic' included:

- laughter

- crying

- general restlessness

- general pain

- fainting

- respiratory problems

- rashes

General mass hysteria causes:

Many of the symptoms experienced during the 'laughter epidemic' were stress-induced due to various external factors. The stress and anxiety that provokes mass hysteria outbreaks are reactions to perceived threats, cultural transitions, instances of uncertainty, and social stressors.[4] Due to the majority of the population affected by this epidemic being young and adolescent children, the outbreak has been attributed to the young not having the appropriate coping skills to manage such stresses and anxieties. Coinciding with this, adolescents have a need for acceptance and are eager to blend into a group, making them vulnerable to influence contagion.[8]

External factors

Linguist Christian F. Hempelmann has theorized that the episode was stress-induced. In 1962, Tanganyika had just won its independence, he said, and students had reported feeling stressed because of higher expectations by teachers and parents. MPI, he says, usually occurs in people without a lot of power. "MPI is a last resort for people of a low status. It's an easy way for them to express that something is wrong."[4]

Sociologist Robert Bartholomew and psychiatrist Simon Wessely both put forward a culture-specific epidemic hysteria hypothesis, pointing out that the occurrences in 1960s Africa were prevalent in missionary schools and Tanganyikan society was ruled by strict traditional elders, so the likelihood is the hysteria was a manifestation of the cultural dissonance between the "traditional conservatism" at home and the new ideas challenging those beliefs in school, which they termed 'conversion reactions'.[9]

Connected events

The laughter epidemic was one of three sequential behavioral epidemics that occurred in the vicinity of Lake Victoria.[4] These three major epidemics were classified as events of mass hysteria or mania. According to Benjamin H. Kagwa's observations in the East African Medical Journal, a notable characteristic is the prevalence of typical symptoms within specific ethnic groups, where the occurrence and propagation of comparable symptoms are aligned with tribal boundaries.[10] As with the hysteria epidemic in Tanganyika, these 'manias' are attributed to the radically shifting culture that began to stray away from the traditional cultural beliefs of local tribes and communities.

"We must not, however, think for one moment that this is peculiar to Africans. There is much historical evidence to prove that emotional upheavals associated with hysteria occur whenever a people's cultural roots and beliefs become suddenly shattered" -Benjamin H. Kagwa[10]

| Location | Start Date | Type of 'Manias' | Symptoms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bukoba, Tanganyika (now Tanzania) | January 1962 | laughter mania | laughter, crying, restlessness, pain, fainting, respiratory problems, rashes, and anxiety/stress |

| Kigezi, Uganda | July 1963 | running mania | running, chest pain, agitation, talkativeness, violence, anorexia, exhaustion, quietness, and depression |

| Mbale, Uganda | November 1963 | running mania | running, chest pain, agitation, talkativeness, violence, anorexia, exhaustion, quietness, and depression |

See also

References

- ↑ Jeffries, Stuart (21 November 2007). "The outbreak of hysteria that's no fun at all". The Guardian. Guardian News and Media Limited.

- 1 2 Provine, Robert R. (January–February 1996). "Laughter". American Scientist. 84 (1): 38–47. Archived from the original on 19 January 2009.

- 1 2 Rankin, A.M.; Philip, A.P.A. (May 1963). "An epidemic of laughing in the Bukoba district of Tanganyika". Central African Journal of Medicine. 69: 167–170. PMID 13973013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Hempelmann, Christian F. (2007). "The Epic Tanganyika Laughter Epidemic Revisited". Humor: International Journal of Humor Research. 20 (1): 49–71. doi:10.1515/HUMOR.2007.003. S2CID 144703655.

- 1 2 3 Radiolab (25 February 2008). "Laughter". WNYC Studios. Retrieved 16 June 2019.

- ↑ Bartholomew, Robert E. (2001). Little Green Men, Meowing Nuns and Head-Hunting Panics: A Study of Mass Psychogenic Illness and Social Delusion. Jefferson, North Carolina: Macfarland & Company. p. 52. ISBN 0-7864-0997-5.

- ↑ Sebastian, Simone (29 July 2003). "Examining 1962's 'laughter epidemic'". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 6 May 2023.

- ↑ Zhao, Gang; Cheng, Quinglin; Dong, Xianming; Xie, Li (13 December 2021). "Mass hysteria attack rates in children and adolescents: a meta-analysis". Journal of International Medical Research. 49 (12). doi:10.1177/03000605211039812. PMC 8829737. PMID 34898296.

- ↑ Bartholomew, Robert; Evans, Hilary (2014). Outbreak! The Encyclopedia of Extraordinary Social Behavior. McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-7888-0.

- 1 2 3 "The Problem of Mass Hysteria in East Africa by Benjamin H. Kagwa. East African Medical Journal, 41 (December 1964), 560-565". Transcultural Psychiatric Research Review and Newsletter. 3 (1): 35–37. April 1966. doi:10.1177/136346156600300113. S2CID 46332096.

External links

- "Information on MPI". Archived from the original on 20 June 2010.

- Article from CBC News

- WNYC radio program with a section discussing the epidemic