| Tango | |

|---|---|

The bandoneon, an accordion-like instrument closely associated with tango | |

| Stylistic origins | |

| Cultural origins | Argentina, Uruguay |

| Subgenres | |

| Fusion genres | |

| Tango-rock | |

| Regional scenes | |

| Other topics | |

| |

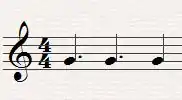

Tango is a style of music in 2

4 or 4

4 time that originated among European and African immigrant populations of Argentina and Uruguay (collectively, the "Rioplatenses").[2] It is traditionally played on a solo guitar, guitar duo, or an ensemble, known as the orquesta típica, which includes at least two violins, flute, piano, double bass, and at least two bandoneóns. Sometimes guitars and a clarinet join the ensemble. Tango may be purely instrumental or may include a vocalist. Tango music and dance have become popular throughout the world.

Origins

Even though present forms of tango developed in Argentina and Uruguay from the mid-19th century, there are records of 19th and early 20th-century tango styles in Cuba and Spain,[3] while there is a flamenco tango dance that may share a common ancestor in a minuet-style European dance.[4] All sources stress the influence of African communities and their rhythms, while the instruments and techniques brought in by European immigrants in the 20th century played a major role in the style's final definition, relating it to the salon music styles to which tango would contribute back at a later stage.

Angel Villoldo's 1903 tango "El Choclo" was first recorded no later than 1906 in Philadelphia.[5] Villoldo himself recorded it in Paris (possibly in April 1908, with the Orchestre Tzigane du Restaurant du Rat Mort),[6] as there were no recording studios in Argentina at the time.

Early tango was played by European immigrants in Buenos Aires and Montevideo.[7][8][9] The first generation of tango players from Buenos Aires was called "Guardia Vieja" (the Old Guard). It took time to move into wider circles; in the early 20th century, it was the favorite music of thugs and gangsters who visited brothels,[10] in a city with 100,000 more men than women (in 1914). The complex dances that arose from such rich music reflect how the men would practice the dance in groups, demonstrating male sexuality and causing a blending of emotion and aggressiveness. The music was played on portable instruments: flute, guitar, and violin trios, with bandoneón arriving at the end of the 19th century. The organito, a portable player-organ, broadened the popularity of certain songs. Eduardo Arolas was the major driver of the bandoneón's popularization, with Vicente Greco soon standardizing the tango sextet as consisting of piano, double bass, two violins, and two bandoneóns.

Like many forms of popular music, tango was associated with the underclass, and attempts were made to restrict its influence. In spite of the scorn, some, like writer Ricardo Güiraldes, were fans. Güiraldes played a part in the international popularization of tango, which had conquered the world by the end of World War I; he wrote the poem "Tango", which describes the music as the "all-absorbing love of a tyrant, jealously guarding his dominion, over women who have surrendered submissively, like obedient beasts".[4]

One song that would become the most widely known of all tango melodies[11] also dates from this time. The first two sections of "La Cumparsita" were composed as an instrumental march in 1916 by teenaged Gerardo Matos Rodríguez of Uruguay.[12][13]

Argentine roots of tango

Besides the global influences mentioned above, early tango was locally influenced by Payada, the Milonga from Argentine and Uruguay pampas, and Uruguayan candombe. In Argentina there was Milonga "from the country" since the mid eighteenth century. The first "payador" remembered is Santos Vega. The origins of Milonga seem to be in the pampa with strong African influences, especially though the local candombe (which would be related to its contemporary candombe in Buenos Aires and Montevideo). It is believed that this candombe existed and was practised in Argentina since the first slaves were brought into the country.[14]

Although the word "tango" to describe a music/dance style had been printed as early as 1823 in Havana, Cuba, the first Argentine written reference is from an 1866 newspaper that quotes the song "La Coqueta" (an Argentine tango).[15] In 1876, a tango-candombe called "El Merenguengué"[16][17] became very popular, after its success in the Afro-Argentines' carnival held in February of that year. It is played with harp, violin, and flute, in addition to the Afro-Argentine candombe drums ("Llamador" and "Repicador"). This has been seriously considered one of the strong points of departure for the birth and development of tango.[18]

The first tango "group" was composed of two Afro-Argentines: "the black" Casimiro Alcorta (violin) and "the mulatto" Sinforoso (clarinet).[19] They played small concerts in Buenos Aires from the early 1870s until the early 1890s. Alcorta is the author of "Entrada Prohibida" (Prohibited Entry),[20] sung by the brothers Teisseire. He is also credited with the tango "Concha sucia", which was later adapted and sung by F. Canaro as "Cara sucia" (Dirty Face).[21]

Before the 1900s, the following tangos were being played: "El queco" (anonymous, attributed to clarinetist Lino Galeano in 1885);[22] "Señora casera" (anonymous, 1880); "Andate a la recoleta" (anonymous, 1880);[22] "El Porteñito" (by the Spaniard Gabriel Diez in 1880);[22] "Tango Nº1" (Jose Machado, 1883); "Dame la lata" (Juan Perez, 1888);[22] "Que polvo con tanto viento" (anonymous, 1890);[22] "No me tires con la tapa de la olla" (A.A. 1893); and "El Talar" (Prudencio Aragon, 1895).[23] One of the first women to write tango scores was Eloísa D'Herbil. She wrote such pieces as "Y a mí qué" (What Do I Care), "Che no calotiés!" (Hey, No Stealing!), and others, between 1872 and 1885.[24][25]

The first recorded musical score is "La Canguela" (1889). The first copyrighted tango score is "El entrerriano", released in 1896 and printed in 1898 by Rosendo Mendizabal, an Afro-Argentine. As for the transition between the old "Tango criollo" (Milonga from the pampas, evolved with touches of Afro-Argentine candombe, and some Habanera), and the tango of the Old Guard, there are the following songs:

- Ángel Villoldo - "El choclo", 1903; "El Pimpolla", 1904; "La Vida del Carretero", 1905; and "El Negro Alegre", 1907

- Gabino Ezeiza - "El Tango Patagones", 1905

- Higinio Cazón - "El Taita", 1905

Moreover, the first tango recorded by an orchestra was "Don Juan", whose author is Ernesto Ponzio. It was recorded by the orchestra of Vicente Greco.[26][27]

1920s and 1930s, Carlos Gardel

Tango soon gained popularity in Europe, beginning in France. Superstar Carlos Gardel soon became a sex symbol who brought tango to new audiences, especially in the United States, due to his sensual depictions of the dance in film. In the 1920s, tango moved out of the lower-class brothels and became a more respectable form of music and dance. Bandleaders like Roberto Firpo and Francisco Canaro dropped the flute and added a double bass in its place. Lyrics were still typically macho, blaming women for countless heartaches, and the dance moves were still sexual and aggressive.

Carlos Gardel became especially associated with the transition from a lower-class "gangster" music to a respectable middle-class dance. He helped develop tango-canción in the 1920s and became one of the most popular tango artists of all time. He was also one of the precursors of the "Golden Age of Tango".

Gardel's death was followed by a division into movements within tango. Evolutionists like Aníbal Troilo and Carlos di Sarli were opposed to traditionalists like Rodolfo Biagi and Juan d'Arienzo.

Golden Age

The "Golden Age" of tango music and dance is generally agreed to have been the period from about 1935 to 1952, roughly contemporaneous with the big band era in the United States. Tango was performed by orquestas típicas, bands often including over a dozen performers.

Some of the many popular and influential orchestras included those of Mariano Mores, Juan d'Arienzo, Francisco Canaro, and Aníbal Troilo. D'Arienzo was called the "Rey del compás" or "King of the beat", for the insistent, driving rhythm which can be heard on many of his recordings. "El flete" is an excellent example of D'Arienzo's approach. Canaro's early milongas are generally the slowest and easiest to dance to; and for that reason, they are the most frequently played at tango dances (milongas); "Milonga Sentimental" is a classic example.

Beginning in the Golden Age and continuing afterwards, the orchestras of Osvaldo Pugliese and Carlos di Sarli made many recordings. Di Sarli had a lush, grandiose sound, and emphasized strings and piano over the bandoneón, which is heard in "A la gran muñeca" and "Bahía Blanca" (the name of his home town).

Pugliese's first recordings were not too different from those of other dance orchestras, but he developed a complex, rich, and sometimes discordant sound, which is heard in his signature pieces "Gallo ciego", "Emancipación", and "La yumba". Pugliese's later music was played for an audience and not intended for dancing, although it is often used for stage choreography for its dramatic potential, and sometimes played late at night at milongas.

Eventually, tango transcended its Latin boundaries as European bands adopted it into their dance repertoires. Non-traditional instruments were often added, such as the accordion (in place of the bandoneon), saxophone, clarinet, ukulele, mandolin, electric organ, etc., as well as lyrics in non-Spanish languages. European tango became a mainstream worldwide dance and popular music style, alongside foxtrot, slow waltz, and rumba. It somewhat diverged from its Argentinian origin and developed characteristic European styles. Famous European band leaders who adopted tango included, to name a few, Otto Dobrindt, Marek Weber, Oskar Joost, Barnabas von Geczy, Jose Lucchesi, Kurt Widmann, Adalbert Lutter, Paul Godwin, Alexander Tsfasman, as well as famous singers Leo Monosson, Zarah Leander, Rudi Schuricke, Tino Rossi, Janus Poplawski, Mieczysław Fogg, Pyotr Leshchenko, and others. The popularity of European tango precipitously declined with the advent of rock-n-roll in the 1950s–60s.[28][29][30][31][32]

Tango nuevo

The later age of tango has been dominated by Ástor Piazzolla, whose "Adiós nonino" became the most influential work of tango music since Carlos Gardel's "El día que me quieras" was released in 1935. During the 1950s, Piazzolla consciously tried to create a more academic form with new sounds breaking the classic forms of tango, drawing the derision of purists and old-time performers. The 1970s saw Buenos Aires developing a fusion of jazz and tango. Litto Nebbia and Siglo XX were especially popular within this movement. In the 1970s and 1980s, the vocal octet Buenos Aires 8 recorded classic tangos in elaborate arrangements, with complex harmonies and jazz influence, and also recorded an album with compositions by Piazzolla.

The so-called post-Piazzolla generation (1980–) includes musicians such as Dino Saluzzi, Rodolfo Mederos, Gustavo Beytelmann, and Juan Jose Mosalini. Piazzolla and his followers developed nuevo tango, a musical genre that incorporated jazz and classical influences into a more experimental style.

In the late 1990s, composer and pianist Fernando Otero[33] continued to add elements to the innovation process which had started decades ago, expanding the orchestration and form while including improvisation and atonal aspects in his work.

1990s–2000s tango

In the second half of the 1990s, a new movement of tango composers and tango orchestras playing new songs was born in Buenos Aires. It was mainly influenced by the old orchestra style rather than by Piazzolla’s renewal and experiments with electronic music.

Over the first two decades of the 21st century, the movement has grown with the creation of countless bands playing new tangos. The most prominent figures leading this phenomenon have been the Orquesta Típica Fernandez Fierro, whose creator, Julian Peralta,[34][35][36][37] would later start Astillero and the Orquesta Típica Julián Peralta. Other bands have also become part of the movement, such as Orquesta Rascacielos, Altertango, Ciudad Baigón, as well as singer-songwriters Alfredo "Tape" Rubín,[34][38] Victoria di Raimondo,[39] Juan Serén,[34][40] Natalí de Vicenzo,[36] and Pacha González.[36][37][40]

Neotango

Tango development did not stop with tango nuevo. 21st-century tango is referred to as neotango. These recent trends can be described as "electro tango" or "tango fusion", where the electronic influences range from subtle to dominant.

Tanghetto and Carlos Libedinsky are good examples of the subtle use of electronic elements. The music still has its tango feeling, the complex rhythmic and melodious entanglement that makes tango so unique. Gotan Project is a group that formed in 1999 in Paris, consisting of musicians Philippe Cohen Solal, Eduardo Makaroff, and Christoph H. Muller. Their releases include Vuelvo al Sur/El capitalismo foráneo (2000), La Revancha del Tango (2001), Inspiración Espiración (2004), and Lunático (2006). Their sound features electronic elements like samples, beats, and sounds on top of a tango groove. Some dancers enjoy dancing to this music, although many traditional dancers regard it as a definite break in style and tradition.

Bajofondo Tango Club is another example of electro-tango. Further examples can be found on the CDs Tango?, Hybrid Tango, Tangophobia Vol. 1, Tango Crash (with a major jazz influence), Latin Tango by Rodrigo Favela (featuring classic and modern elements), NuTango, Tango Fusion Club Vol. 1 by the creator of the milonga called "Tango Fusion Club" in Munich, Felino by the Norwegian group Electrocutango, and Electronic Tango, a compilation CD. In 2004, the music label World Music Network released a collection under the title The Rough Guide to Tango Nuevo.

Musical impact and classical interpreters

Although tango music was strictly circumscribed to the tango interpreters, it was the classically trained Argentinian pianist Arminda Canteros (1911–2002) who used to play tangos to satisfy the requests of her father, who could not understand classical music. She developed her own style and had a weekly program of tango music for a radio station in Rosario, Argentina in the 1930s and 1940s. Since tango playing was considered the epitome of machismo, she had to take the masculine pseudonym "Juancho" for the broadcasts.[41][42]

Canteros settled in New York City in 1970, where in 1989, she recorded the album Tangos, at the age of 78.[43] Following Cantero’s example, another Argentinian female pianist brought tango music to the concert halls: Cecilia Pillado played a complete tango recital at the Berliner Philharmonie in 1997 and recorded that program for her CD Cexilia’s Tangos.[44]

Since then, tango has become part of the repertoire for great classical musicians like the baritone Jorge Chaminé with his Tangos, recorded with bandoneónist Olivier Manoury. Additionally, al Tango, Yo-Yo Ma, Martha Argerich, Daniel Barenboim, Gidon Kremer, Plácido Domingo, and Marcelo Álvarez have performed and recorded tangos.

Some classical composers have written tangos, such as Isaac Albéniz in España (1890), Erik Satie in Le Tango perpétuel (1914), and Igor Stravinsky in Histoire du Soldat (1918). Nikolai Myaskovsky composed an Argentinian death tango for the poem "War and Peace". Kurt Weill continued this style in The Threepenny Opera (1928) (Die Dreigroschenoper), with "Tango Ballade", or "Zuhälterballade", a fateful song about underworld life (a symphonic version commissioned by Otto Klemperer); a bit later, he composed "Youkali" (Tango-Habanera), with French lyrics. Also noteworthy was the accordionist John Serry Sr., who composed "Tango of Love" and "Petite Tango" for accordion quartet (1955).[45] The list of composers who wrote inspired by tango music also includes John Cage in "Perpetual Tango" (1984), John Harbison in "Tango Seen from Ground Level" (1991), and Milton Babbitt in "It Takes Twelve to Tango" (1984). The influence of Piazzolla has fallen on a number of contemporary composers. The "Tango Mortale" in Arcadiana by Thomas Adès is an example.

Many popular songs in the United States have borrowed melodies from tango: the earliest published tango, "El Choclo", lent its melody to the fifties hit "Kiss of Fire". Similarly, "Adiós Muchachos" became "I Get Ideas", and "Strange Sensation" was based on "La Cumparsita".

Showing tango music's continued popularity, multiple international radio stations broadcast nonstop tango music today.[46]

See also

References

- ↑ Blatter, Alfred (2007). Revisiting Music Theory: A Guide to the Practice (New York: Routledge), p. 28. ISBN 978-0-415-97439-4 (cloth); ISBN 978-0-415-97440-0 (pbk).

- ↑ Termine, Laura (30 September 2009). "Argentina, Uruguay bury hatchet to snatch tango honor". Buenos Aires. Archived from the original on 27 February 2014. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

- ↑ José Luis Ortiz Nuevo El origen del tango americano Madrid and La Habana 1849

- 1 2 Christine Denniston. Couple Dancing and the Beginning of Tango 2003

- ↑ "Victor matrix B-3624. El choclo / Victor Argentine Orchestra". Discography of American Historical Recordings. Univ. of Calif. Retrieved 19 November 2017.

- ↑ Tangocommuter (28 July 2014). "Ángel Villoldo, Paris and early tango". Retrieved 19 November 2017.

- ↑ Norese, María Rosalía: Contextualization and analysis of tango. Its origins to the emergence of the avant-garde. University of Salamanca, 2002 (restricted online copy, p. 5, at Google Books)

- ↑ "Investigando el Tango – Tésis Doctoral – Dra. Marta Rosalía Norese". Archived from the original on 24 September 2016. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- ↑ "Todotango.com – Todo sobre el tango argentino". Archived from the original on 3 November 2013. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- ↑ Tango and whores (in Spanish)

- ↑ McLean, Michael (May 2008). Care to Tango?, Book 2. Alfred Music. ISBN 978-0-7390-5100-9.

- ↑ ToTANGO. LA CUMPARSITA – Tango's Most Famous Song Archived 30 December 2005 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ TodoTango. Ricardo García Blaya. Tangos and Legends: La Cumparsita Archived 10 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Revista Quilombo – Noticias, columnas, articulos y opiniones" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 March 2012. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- ↑ "Notas - Historia del Tango - El nacimiento del Tango - hlm!.Tango - Hágase la música - hagaselamusica.com". Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- ↑ Tango-candombe afroargentino "El Merenguengué". Archived 21 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Jorge Gutman

op. cit. - ↑ Museum House of Carlos Gardel “The Black history of Tango”. Archived 6 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ www.RrinconDelTango.com. ""Historia del tango-Los primitivos conjuntos" por Tesy Cariaga – Buenos Aires – Argentina.- .: Rincón del Tango :". Archived from the original on 12 July 2006. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- ↑ El negro Casimiro Alcorta, y su tango "Entrada Prohibida". Archived 6 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ El negro Casimiro Alcorta, y su tango "Concha Sucia".

- 1 2 3 4 5 Scholz, Cora (2008). Tango argentino—seine Ursprünge und soziokulturelle Entwicklung (in German). GRIN Verlag. p. 19. ISBN 978-3-640-11862-5.

- ↑ "Lugares de baile". Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- ↑ Horvath, Ricardo (2006). Esos malditos tangos: apuntes para la otra historia (in Spanish). Buenos Aires, Argentina: Editorial Biblos. p. 61. ISBN 978-950-786-549-7.

- ↑ Ostuni, Ricardo (22 November 2011). "La baronesa del tango" [The baroness of tango] (in Spanish). Buenos Aires, Argentina: InfoNews. Archived from the original on 14 July 2017. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- ↑ "Todotango.com – Todo sobre el tango argentino". Archived from the original on 16 May 2013. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- ↑ "Todotango.com – Todo sobre el tango argentino". Archived from the original on 23 March 2014. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- ↑ Jürgen Wölfer Jazz in Deutschland – Das Lexikon. Alle Musiker und Plattenfirmen von 1920 bis heute. Hannibal Verlag: Höfen 2008, ISBN 978-3-85445-274-4

- ↑ Michael H. Kater: Gewagtes Spiel. Jazz im Nationalsozialismus. Cologne 1995, ISBN 3-423-30666-1.

- ↑ Schnoor, Hans: Barnabás von Géczy. Aufstieg einer Kunst. Dresden: Verlag der Dr. Güntzschen Stiftung o.J.(um 1937) mit Diskografie B.v.G. auf Electrola-Schallplatten.

- ↑ Драгилёв, Д. Лабиринты русского танго. — СПб.: Алетейя, 2008. — 168 с — ISBN 978-5-91419-021-4

- ↑ Bruce Bastin, notes to "German Tango Bands 1925–1939", Harlequin CD HQCD-127

- ↑ Michael Hill. "About Fernando Otero". Nonesuch Records. Retrieved 13 May 2013.

- 1 2 3 "Julián Peralta: La selección de los tangos nuevos". Retrieved 9 October 2016.

- ↑ Cas, Andrés. "Levantar al tango de su siesta". Clarin.com. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Tangos de estreno: clásicos de las orquestas del futuro". Retrieved 9 October 2016.

- 1 2 tiempoar.com.ar. ""Pensamos al tango como una música popular" – tiempoar.com.ar". tiempoar.com.ar. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

- ↑ Peters, Lucas. "Tango, te cambiaron la pinta". Clarin.com. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

- ↑ "Di Raimondo: Cantar en una orquesta típica es un sueño". Diario Uno. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

- 1 2 "Canción porteña en el festival de tango". Retrieved 9 October 2016.

- ↑ JohnDavidChapman (8 August 2011). "Arminda Canteros, pianist, plays Invierno Porteño by Astor Piazzolla". Archived from the original on 21 December 2021. Retrieved 2 August 2016 – via YouTube.

- ↑ "El Tango y sus invitados: Arminda Canteros". Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- ↑ "El Tango y sus invitados: Arminda Canteros – Tangos(Solos de piano)-1989". Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- ↑ "Tango Malambo – Cecilia Pillado´s Label". Archived from the original on 17 August 2016. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- ↑ Library of Congress- Copyright Office, Tango of Love, Petite Tango. Copyright – Alpha Music Co., New York, NY. Composer: John Serry Sr. 1955

- ↑ Argentine Tango Radio