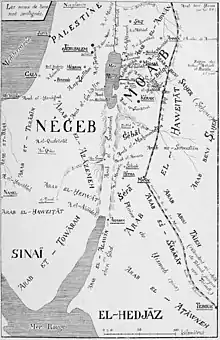

The Tirabin (Arabic: الترابين), were the most important Arab tribe in the Sinai Peninsula during the 19th century, and the largest inside Negev. Today this tribe resides in the Sinai Peninsula but also in Cairo, Ismailia, Giza, Al Sharqia and Suez, Israel (Negev), Jordan, Saudi Arabia and the Gaza strip.[1] A township named Tirabin al-Sana was built in Israel in 2004 especially for the members of al-Sana clan from Al-Tirabin tribe.

Al-Tirabin is considered the largest Bedouin tribe in the Negev and Sinai Peninsula and all Egypt, with over 500,000 people.

Origin

Tarabin traced their ancestry to one 'Atiya who belonged to the Quraysh tribe,[2] to which Mohammed the prophet of Islam belonged, and lived at Turba east of Mecca. It is believed that 'Atiya migrated to Sinai in the 14th Century. He was buried at al-Sharaf near Suez. 'Atiya had five sons to which various clans of the Tarabin trace their descent. Musa'id was remembered as ancestor of the Qusar; Hasbal of the Hasabila; Nab'a of the Naba'at; Sari of the Sarayi'a. These four sections lived in Sinai.[3]

Sinai Tarabin

The Sinai Tarabin Bedouin are currently located just north of Nuweiba and arrived to the peninsula around 300 years ago.[4] In 1874 they are recorded in a list of Bedouin, produced by the Palestine Exploration Fund, as "in the Desert of the Tih".[5]

Transformation of the Bedouin society and its problems

The past few decades have proved difficult for traditional Bedouin culture. Due to the changing surrounding and erection of new resort towns such as Sharm el-Sheikh Bedouin lifestyle is changing, too. Their once-nomadic culture is transforming and these changes are not easy for the community. We can see the erosion of traditional values and this community faces relatively new challenges, such as unemployment and various land issues. With urbanization and new education opportunities offered, Bedouin started to marry people outside their tribe which once was completely inappropriate.[1]

Unemployment issues

Bedouins living in the Sinai peninsula generally did not benefit from employment in the initial construction boom due to low wages offered. Sudanese and Egyptians workers were brought here as construction laborers instead. When the tourist industry started to bloom, local Bedouin increasingly moved into new service positions such as cab drivers, tour guides, campgrounds or cafe managers. However, the competition is very high, and many Sinai Bedouin are unemployed. Moreover, because of their traditional way of life, Bedouin women are usually not allowed to work outside their house.

Smuggling

Since there are not enough employment opportunities, Tarabin Bedouin as well as other Bedouin tribes living along the border between Egypt and Israel are involved in inter-border smuggling of drugs and weapons,[1] as well as infiltration of prostitutes and African labor workers.

Land issues

In most countries in the Middle East the Bedouin have no land rights, only users’ privileges,[6] and it is especially true for Egypt. Since the mid-1980s, the Bedouin who held desirable coastal property have lost control of much of their land as it was sold by the Egyptian government to hotel operators. Egypt did not see it as the land that belongs to Bedouin tribes, but rather as a state property.

In the summer of 1999, the latest dispossession of land took place when the army bulldozed Bedouin-run tourist campgrounds north of Nuweiba as part of the final phase of hotel development in the sector, overseen by the Tourist Development Agency (TDA). The director of the Tourist Development Agency dismissed Bedouin rights to most of the land, saying that they had not lived on the coast prior to 1982. Their traditional semi-nomadic culture has left Bedouin vulnerable to such claims.[7]

Attitude of Egyptian authorities

After the Egyptian Revolution of 2011, the Sinai Bedouin were given an unofficial autonomy due to political instability inside the country. But Egyptian authorities traditionally view the Bedouin cross-border ties with Israel, Jordan and Saudi Arabia with suspicion.[8] The Ouda Tarabin case is a good example of it.

Negev Tarabin

The descendants of 'Atiya's son Nijm lived around Beersheba, in what is now called the Negev. Nijm had two sons from which the two branches of the Negev Tarabin trace their line: the Nijmat and the Ghawali. The Nijmat were regarded as the paramount clan. Tradition has it that in time of war they would lead the whole tribe into battle. One of Nijm's grandsons is said to have journeyed to the Indian Subcontinent due to blood feuds with other tribes. His family is believed to have finally settled in the Punjab region while travelling with trade caravans and armies.

Tarabin Khokhar are a subsection of the Khokhar tribe who have been proven to have originated from a Quraysh Bedouin named Atiya. Atiya lived in Turba east of Mecca. He migrated to the Sinai peninsula in the 14th Century. He had five sons who together form the Arab et Tarabin tribe, whose inhabitants still reside in the Sinai and the Negev desert. Some migrated or settled down in Palestine, Egypt and Syria during Ottomon rule. One of his sons, Nijm and his two sons formed the most powerful clan of the Tarabin known as the Nijma't. The Tarabin Khokhar trace their ancestry from Suleman, the grandson of Nijm ibn Atiya. Suleman migrated from the Sinai to Syria as a result of a blood feud with a rival bedouin tribe. Name of the rival tribe is not known, but the Tiyaha are suspected to be the rivals. The descendants of Suleman continued their migration eastward and finally settled in riverlands of the Punjab. The brawn of the Tarabin Bedouin made them great recruits in the army of various Sultans of Iran and the Indian subcontinent. Successive generations changed from Tarabin to Tarabin Khokhar as a result of honors awarded to them. Intact family trees of Tarabin Khokhars tracing there ancestry back to Atiya from Nijm survive to this day. Latest genealogical evidence has corroborated this claim of descent.

In modern times, in 1915, the Nijmat leader Hammad Pasha al-Sufi led a force of 1,500 bedouin under Turkish command in their attack on the Suez Canal. He was head of the Turkish administration in Beersheba and died in 1924. The Ghawali had nine sub-sections. The most prominent was the Satut, who in 1873, under Sheikh Saqr ibn Dahshan Abu Sitta, had to leave their traditional land following a blood feud and sided with the Tiyaha in the war between them and the Tarabin. One of the Satut leaders, 'Aqib Saqr, was well known as a military leader. Khedive Isma'ail gave him land in Faqus district. The Turks exiled him to Jerusalem, where he died. His son Dahshan distinguished himself in the war with the 'Azazma, particularly at the Fight of Ramadan. He and some of his fighters migrated to Transjordania where they attached themselves to the Bani Saqr. During this time the leadership of the Ghawali was taken by the Zari'iyin clan. Their leader in 1915 was Salim who had to flee the Turkish authorities and was succeeded by 'Abd al Karim who died in 1931. He was succeeded by Muhammad Abu Zari.[9]

Sedentarization

Negev Bedouins experience similar problems to those encountered in Egypt. Prior to the establishment of Israel, the Negev Bedouins were a semi-nomadic society that had been through a process of sedentariness since the Ottoman rule of the region. By 1931, there were roughly 17,000 of them in Palestine[10] almost 90% worked in agriculture rather than solely raising livestock, and had clearly defined rules about land ownership.[11] After 1948, about 11,000 Bedouin remained in the Negev out of a pre-war population of between 65,000 and 95,000. Only 19 of the original 95 tribes were left. Those who remained were relocated by the IDF to an area east and south east of Beersheba called Siyag (fence in Hebrew).[12]

In 1969–1989, seven Bedouin townships with developed infrastructure were established in order to urbanize Tarabin and other Bedouin tribes and give them better life conditions. This policy so far proved only partially successful, as with erection of new villages and towns and some Bedouin population moving into brand new houses, it created several new problems. First, the townships were completely urban, and Bedouin prefer to live in rural-type settlements. It was one of the reasons why a part of the Bedouin society refused to move into new localities. But later on, this mistake was fixed by Israeli authorities.

As of process of sedentarization, it is full of hardships for any nation, since it means a harsh shift from one way of life to another – transition from wandering to permanent residence. Bedouin society based on tradition also experienced plenty of problems. The rate of unemployment remains high in bedouin townships, as well as crime level.[13] School through age 16 is mandatory by law, but the vast majority of the population does not receive a high school education although schooling is much more accessible now. Women are discriminated in the patriarchal-type Bedouin society.[14]

Approximately half the 170,000 Negev Bedouin live in 39 unrecognised villages without connection to the national electricity, water and telephone grids. The bedouin consist of 25% of the population of the Northern Negev and have jurisdiction over less than 2% of the land. Seven of the bedouin townships are amongst the 8 poorest localities in Israel.[15]

Land issues

Israeli Law is based mainly on Mandatory law, which in turn derives to a great extent from the Ottoman law. According to the Israeli Law, land ownership has to be registered in the land registry. One cannot claim land ownership unless he or she can prove that it is registered in a proper way. The process of land registration was started in the late Ottoman empire. But due to their semi-nomadic way of life, Bedouin did not realize the need to register their ownership rights since it brought with it responsibility to pay taxes, and they suffered from it later.

In the mid-1970s, Israel let the Negev Bedouin register their land claims and issued special land claim certificates that served as the basis for the "right of possession" later granted by the government. These certificates served as the base for paying compensations to some 5000 Negev Bedouin when, following the signing of the Treaty of Peace with Egypt, there was a need to move an airport from Sinai to a Bedouin locality. After negotiations, all the local land claim certificate holders received money compensations and moved to Bedouin townships, where they built new houses and started businesses.[6]

As of today, there is a problem of trespassing on state lands and building unrecognized Bedouin settlements having no municipal status and facing demolition orders,[16] although all the Negev Bedouin have a permanent housing solution for them.

Attitude of Israeli authorities

In 2011 the Prawer Commission published its suggestion for relocation 30.000-40.000 Bedouin to government-approved townships.[17][18] This plan did not specify the means of doing it and has been criticized by the European Parliament.[19] After prolonged negotiations three agreements were made between the state authorities and the Tarabin Bedouin. As a consequence, the remainder of this tribe voluntarily moved into a state build settlement of Tirabin al-Sana.

A solar project

In 2011 an Israeli solar energy company Arava Power signed a contract with the Tarabin tribe in the Negev Desert to build a solar installation.[20] The company is negotiating with the government a 30% of Israel's guaranteed solar power feed-in tariff caps set apart just for the Bedouin people. A plan for a photovoltaic solar installation was approved by Ministry of Interior's Southern Regional Planning and Building Committee in September 2011.[21]

Members of the community

- Ouda Tarabin, an Israeli Bedouin imprisoned by Egypt for illegal border crossing[22]

- Haj Mousa Tarabin, a community leader[23]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Tamim Elyan, Metropolitan Bedouins: Tarabin tribe living in Cairo between urbanization and Bedouin traditions, Daily News Egypt

- ↑ Bedouin in the Negev desert Archived 2009-11-14 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Palestine Exploration Quarterly. (October 1937) Notes on the Bedouin Tribes of Beersheba District I. by S. Hillelson. Pages 243- 246.

- ↑ "Sinai on the Red Sea". Archived from the original on December 21, 2011. Retrieved February 19, 2012.

- ↑ Palestine Exploration Fund. Quarterly Statement for 1875. Page 28.

- 1 2 Dr. Yosef Ben-David (1999-07-01). "The Bedouin in Israel". Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

- ↑ Bedouins – the original inhabitants of Sinai

- ↑ Ed Douglas, Inside the Bedouin's secret garden, The Observer, The Guardian, September 23, 2007

- ↑ Palestine Exploration Quarterly. (October 1937) Notes on the Bedouin Tribes of Beersheba District I. by S. Hillelson. Pages 243- 246.

- ↑ "Census of Palestine, 1931".

- ↑ Human Rights Watch (March 2008 Vol 20, No 5) Off the Map. Land and Housing Rights Violations in Israel's Unrecognised Bedouin Villages. pp. 1,12.

- ↑ HRW. p. 12

- ↑ Blueprint Negev. Working with Bedouin communities

- ↑ Sarab Abu-Rabia-Queder The activism of Bedouin women: Social and political resistance Ben Gurion University

- ↑ HRW. pp. 1,3,10,91.

- ↑ Bedouins in the State of Israel Knesset official site

- ↑ Al Jazeera, 13 September 2011, Bedouin transfer plan shows Israel's racism

- ↑ Guardian, 3 November 2011, Bedouin's plight: "We want to maintain our traditions. But it's a dream here"

- ↑ Haaretz, 8 July 2012, European Parliament condemns Israel's policy toward Bedouin population

- ↑ Israeli solar company helps Bedouin profit from the sun The Consulate General of Israel to the southeast of Atlanta, November 16, 2011

- ↑ Sine shines on Bedouin Alondon, December 4, 2011

- ↑ Topic: Ouda Tarabin The Times of Israel

- ↑ Nathan Jeffay, Bedouin 'dream comes true' with solar field The Jewish Chronicle, February 23, 2012

Bibliography

- Guérin, Victor (1869). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). Vol. 1: Judee, pt. 2. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale. (pp. 267, 269)

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. Vol. 1. Boston: Crocker & Brewster. (pp. 92, 202, 230 to 274)

- Palmer, E.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund. (p.420)

External links

- A Facebook page devoted to Tarabin Bedouins

- Bedouins in South Sinai

- Lands of the Negev, a short film presented by Israel Land Administration describing the challenges faced in providing land management and infrastructure to the Bedouins in Israel's southern Negev region