Tashigang

བཀྲ་ཤིས་སྒང་་ | |

|---|---|

| Zhaxigang Village | |

Tashigang | |

| Coordinates: 32°30′35″N 79°40′34″E / 32.50972°N 79.67611°E | |

| Country | China |

| Region | Tibet |

| Prefecture | Ngari Prefecture |

| County | Gar County |

| Postal code | 859000 |

| Area code | 0897 |

| Zhaxigang | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 扎西崗村 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 扎西岗村 | ||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Zhā xī gǎng cūn | ||||||

| Literal meaning | "Tashigang Village" | ||||||

| |||||||

Tashigang[1][lower-alpha 1] (Tibetan: བཀྲ་ཤིས་སྒང་, Wylie: bkra shis sgang, THL: tra shi gang, transl. "auspicious hillock"),[9] with a Chinese spelling Zhaxigang (Chinese: 扎西崗村; pinyin: Zhā xī gǎng cūn), is a village in the Gar County of the Ngari Prefecture, Tibet.[10][11][12] The village forms the central district of the Zhaxigang Township. It houses an ancient monastery dating to the 11th century.

Geography

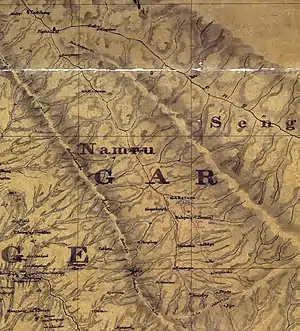

Tashigang is in the Indus Valley, close to the border with Ladakh (Indian union territory), near the confluence of the Sengge Zangbo and Gartang rivers (the two headwaters of the Indus River).[4] Sven Hedin described the Tashigang monastery as follows:

Right in front of us the monastery Tashi-gang gradually grows larger. Its walls are erected on the top of an isolated rock of solid porphyrite, which crops up from the bottom of the Indus valley like an island drawn out from north to south. ... on the short side stand two round free-standing towers, ... The whole is surrounded by a moat 10 feet deep...[13]

Tashigang was described by European travellers in the 18th and 19th centuries as the first Tibetan village, as they travelled from Ladakh towards Kailas–Manasarovar.[8] It was at a distance of a day's march from Demchok, which was regarded as the Ladakh–Tibet border since the 17th-century Treaty of Tingmosgang between the two nations.[14]

History

Early medieval period

During the Tibetan Era of Fragmentation, Kyide Nyimagon, a descendant of emperor Langdarma escaped to Western Tibet (then called Ngari or Ngari Khorsum) and established a small kingdom at Rala in the Sengge Zangbo valley close to Tashigang. He built a red fort (Kharmar).[lower-alpha 2][18] (See Strachey's map for Rala.) Subsequently, Nyimagon expanded his kingdom to the entire Ngari. After his death, the kingdom was divided among his three sons, the eldest son receiving Maryul (Ladakh and Rudok), the second son receiving Guge-Purang and the third son Zanskar (in western Ladakh). According to the current interpretations of the sources, Ladakh's southern border was at Demchok Karpo, a stony white peak beside the Ladakhi village of Demchok.[19] This would lead to the conclusion that Tashigang and the original Kharmar fort were part of Guge.

Medieval period

A monastery was founded at Tashigang by the New Tantra Tradition school of Rinchen Zangpo during the 10th–11th centuries.[20] During the 13th–14th centuries, it was converted into a Kagyu monastery, along with several others in western Guge. Karl Ryavec suggests that this may have happened due to some political decline in the kingdom.[21]

Ladakhi ruler Sengge Namgyal (r. 1616–1642) conquered and annexed Guge in 1630.[22] He is credited with building a new monastery at Tashigang.[23] It was a Drukpa monastery associated with Taktsang Repa.[24][25]

During the reign of Sengge Namgyal's successor, Deldan Namgyal, Ladakh faced an invasion from Central Tibet under the Fifth Dalai Lama, who was at that time being assisted by the Mongol army. The forces defeated the Ladakhis in Guge, key battles being fought near Rala, and then invaded Ladakh itself.[26] After three years of siege, the Ladakhis requested the help of Kashmiris (under Mughal empire), who drove them out of Ladakh. The retreating troops fled to Tashigang where they ensconced themselves in its fort.[27]

Twenty five Mongol military officers are said to have settled in Tashigang. In 1715, the Jesuit missionary Ippolito Desideri found the region garrisoned by a body of "Tartar" (Mongol) and Tibetan troops, headed by a "Tartar prince". Even today, their descendants are called sog dmag ("the twenty-five Mongol Warriors"). The Drukpa monastery of Tashigang was converted to the Gelugpa order.[24][28]

Modern period

Demographics

In 2013, Zhaxigang Village consisted of 111 households with a total of 332 people.[29]

Notes

- ↑ Alternative spellings include Trashigang,[2] Tashikang,[3] Tashigong[4][5] and Tashegong.[6] Older spellings were "Tushigung" (also "Chang Tushigung"),[1] "Trescy-Khang", and "Tuzhzheegong".[7][8]

- ↑ The ruins of a red fort claimed to have been built by Nyimagon are located at 32°28′56″N 79°51′33″E / 32.48230°N 79.85917°E.[15][16] A close-up photograph was published in Chinese National Geography.[17]

References

- 1 2 Lange, Decoding Mid-19th Century Maps (2017), p. 354.

- ↑ Shakabpa, One Hundred Thousand Moons (2009), pp. 583–584.

- ↑ Strachey, Capt. H. (1853). "Physical Geography of Western Tibet". The Journal of the Royal Geographical Society, Volume 23. Royal Geographical Society (Great Britain). pp. 1–68.

- 1 2 Gazetteer of Kashmir and Ladak (1890), p. 374.

- ↑ Arpi, Claude (December 2016) [abridged version published in Indian Defence Review, 19 May 2017], The Case of Demchok (PDF)

- ↑ Cheema, Crimson Chinar (2015), p. 108.

- ↑ Report of the Officials, Indian Report (2016), p. 42 (SW80).

- 1 2 Fisher, Rose & Huttenback, Himalayan Battleground (1963), pp. 105–106: "The earliest of these was the account by an Italian Jesuit, Ippolito Desideri, who traveled this route in 1716 and who described "Trescy-Khang" (Tashigong) as a "town on the frontier between Second and Third Tibet [i.e., between Ladakh and Tibet]". In 1820, J. B. Fraser published an itinerary of this same route which indicated that "Donzog [Demchok], thus far in Ludhak" was reached on the eleventh stage and on the following day "Tuzhzheegong (a Chinese fort)."

- ↑ "Tashigang Border Defense Company's "defense those things"". China Youth Daily. 4 November 2011. Archived from the original on 8 January 2012.

- ↑ "Introduction to Zhaxigang Village". www.tcmap.com.cn. Retrieved 8 September 2021.

- ↑ "Tibetan departments to change the style of work". China News Service. 16 October 2013.

- ↑ "Tibet 10,000 cadres relayed to the village work to serve the masses". www.gov.cn. 16 November 2015.

- ↑ Lange, Decoding Mid-19th Century Maps (2017), p. 356.

- ↑ Emmer, the Tibet-Ladakh-Mughal War (2007), pp. 99–100: "The frontier with Tibet was fixed at the Lha ri stream at Bde mchog (Demchok), approximately at that place where it is even today."

- ↑ Ryavec, A Historical Atlas of Tibet (2015), p. 73.

- ↑ "Rè lā hóng bǎo" 热拉红堡 [Rala Red Fort]. Ali Regional Tourism Bureau. Retrieved 10 July 2022 – via 57tibet.com.

- ↑ Zhao, Chunjiang; Gao, Baojun (May 2020). Lei, Dongjun (ed.). "Xīzàng diǎn jiǎo cūn, qiánfāng jù yìndù diāobǎo jǐn 600 mǐ" 西藏典角村,前方距印度碉堡仅600米 [Dianjiao Village in Tibet, only 600 meters away from the Indian Bunker in front]. Chinese National Geography. Image 7. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

- ↑ Ahmad, The Ancient Frontier of Ladakh (1960), p. 313.

- ↑ Ahmad, New Light on the Tibet-Ladakh-Mughal War (1968), p. 340.

- ↑ Ryavec, A Historical Atlas of Tibet (2015), p. 75.

- ↑ Ryavec, A Historical Atlas of Tibet (2015), p. 77.

- ↑ Fisher, Rose & Huttenback, Himalayan Battleground (1963).

- ↑ Prem Singh Jina (1996), Ladakh: The Land and the People, Indus Publishing, p. 88, ISBN 978-81-7387-057-6

- 1 2 Jinpa, Why did Tibet and Ladakh Clash? (2015), pp. 134–135.

- ↑ Handa, Buddhist Western Himalaya (2001): "During the reign of Senge Namgyel and his successor, Deldan Namgyel,... the Mahasiddha [Taktsang Repa] got many monasteries built. Magnificent monasteries were built at Hemis, Theg-mchog (Chemrey), Anle [Hanle] and Tashigong."

- ↑ Petech, Luciano (September 1947), "The Tibetan-Ladakhi Moghul War of 1681–83", The Indian Historical Quarterly, 23 (3): 178 – via archive.org

- ↑ Emmer, Gerhard (2007), "Dga' Ldan Tshe Dbang Dpal Bzang Po and the Tibet-Ladakh-Mughal War of 1679–84", Proceedings of the Tenth Seminar of the IATS, 2003. Volume 9: The Mongolia-Tibet Interface: Opening New Research Terrains in Inner Asia, BRILL, p. 98, ISBN 978-90-474-2171-9

- ↑ Dorje, Gyurme (1999), Footprint Tibet Handbook with Bhutan (2nd ed.), Bath: Footprint Handbooks, pp. 354–355, ISBN 0-8442-2190-2 – via archive.org

- ↑ "The basic situation of each township in Gaer County". www.xzge.gov.cn. 19 March 2015. Archived from the original on 28 July 2017.

Bibliography

- Gazetteer of Kashmir and Ladak, Calcutta: Superintendent of Government Printing, 1890

- Palat, Madhavan K., ed. (2016) [1962], "Report of the Officials of the Governments of India and the People's Republic of China on the Boundary Question", Selected Works of Jawaharlal Nehru, Second Series, Volume 66, Jawaharlal Nehru Memorial Fund/Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-01-994670-1-3 – via archive.org

- Ahmad, Zahiruddin (July 1960), "The Ancient Frontier of Ladakh", The World Today, 16 (7): 313–318, JSTOR 40393242

- Ahmad, Zahiruddin (September–December 1968), "New Light on the Tibet-Ladakh-Mughal War of 1679–84", East and West, Istituto Italiano per l'Africa e l'Oriente (IsIAO), 18 (3/4): 340–361, JSTOR 29755343

- Cheema, Brig Amar (2015), The Crimson Chinar: The Kashmir Conflict: A Politico Military Perspective, Lancer Publishers, pp. 51–, ISBN 978-81-7062-301-4

- Emmer, Gerhard (2007), "Dga' Ldan Tshe Dbang Dpal Bzang Po and the Tibet-Ladakh-Mughal War of 1679-84", Proceedings of the Tenth Seminar of the IATS, 2003. Volume 9: The Mongolia-Tibet Interface: Opening New Research Terrains in Inner Asia, BRILL, pp. 81–108, ISBN 978-90-474-2171-9

- Fisher, Margaret W.; Rose, Leo E.; Huttenback, Robert A. (1963), Himalayan Battleground: Sino-Indian Rivalry in Ladakh, Praeger – via archive.org

- Handa, O. C. (2001), Buddhist Western Himalaya: A politico-religious history, Indus Publishing, ISBN 978-81-7387-124-5

- Jinpa, Nawang (Autumn 2015), "Why Did Tibet and Ladakh Clash in the 17th Century?: Rethinking the Background to the 'Mongol War' in Ngari (1679-1684)", The Tibet Journal, 40 (2): 113–150, JSTOR /tibetjournal.40.2.113

- Lange, Diana (2017), "Decoding Mid-19th Century Maps of the Border Area between Western Tibet, Ladakh, and Spiti", Revue d'Etudes Tibétaines,The Spiti Valley Recovering the Past and Exploring the Present

- Ryavec, Karl E. (2015), A Historical Atlas of Tibet, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0-226-24394-8

- Shakabpa, Tsepon Wangchuk Deden (2009), One Hundred Thousand Moons: An Advanced Political History of Tibet, BRILL, ISBN 978-90-04-17732-1

External links

- Zhaxigang Township, OpenStreetMap, retrieved 8 September 2021.