| Temple of Claudius | |

|---|---|

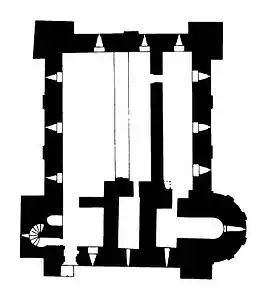

Floor plan | |

| General information | |

| Type | Roman temple |

| Architectural style | Classical |

| Location | Colchester, England |

| Address | CO1 1TJ |

| Completed | 49 AD |

| Demolished | c. 60 AD (original temple); 1070-1080 AD (second temple) |

The Temple of Claudius (Lat. Templum Claudii) or Temple of the Deified Claudius (Lat. Templum Divi Claudii) was a large octastyle temple built in Camulodunum, the modern Colchester in Essex.[1][2] The main building was constructed between 49 and 60 AD, although additions were built throughout the Roman-era.[3] Today, it forms the base of the Norman Colchester Castle.[1][4] It is one of at least eight Roman-era pagan temples in Colchester,[5] and was the largest temple of its kind in Roman Britain;[1][4] its current remains potentially represent the earliest existing Roman stonework in the country.[4]

History

After the Roman conquest of Britain led in person by the Emperor Claudius in 43 AD, a legionary fortress was established at Camulodunon, the Iron Age capital of the Trinovantes and Catuvellauni tribes.[1] This fortress was later converted into a town for retired soldiers in 49 AD,[6] and was renamed Camulodunum, a Latin rendition of the Celtic name of the site.[1] The town was the capital of the new province of Britannia,[1] and had several public buildings befitting its status.[5] These included a theatre, a curia (council chamber), forum and a large classical-style temple.[4][5] The temple's construction began during Claudius' reign, and it was dedicated to him after his death in 54 AD,[1][5] with the official name of the town becoming Colonia Claudia Victricensis ('the City of Claudius' Victory') and the temple becoming the Templum Divi Claudii ('the Temple of the Deified Claudius').[1] The temple was the centre for the imperial cult in the province, as is mentioned in Seneca's 1st-century book the Apocolocyntosis, which mocks both the deceased Claudius and the Britons for their supposed piety[7] towards him.[8][9]

Construction

The podium of the temple was constructed by pouring a mix of mortar and stone into trenches cut into the ground.[1] This base still survives today, and from the position of its load-bearing walls can be made out the superstructures layout.[1] This appears to conform to the plans of Vitruvius in his De Architectura for a classical octastyle temple.[1][2][5]

The podium is rectangular, aligned north–south. The main chamber of the temple, the cella, was positioned at the back of the podium, and would have been a 285-square-metre (3,070 sq ft) rectangular room (its length based on the position of the podium's vaults, would have been one and a quarter its width, in keeping with Vitruvian design)[1] and was also aligned north–south, with a southern entrance.[1] It would have had no windows and, based on Vitruvian geometry and analogies from elsewhere combined with the knowledge from the existing dimensions of the podium, would have been about 20 metres (66 ft) high.[1] The cella's back wall was against the back of the podium.[1] Ten columns would have run along the east and west exterior sides of the temple, with none around the back of the chamber (peripteral style).[1] Eight columns would have run across the front of the cella (hence "octastyle").[1] The pronaos in front of the cella would have had six columns along its sides.[1] The temple was eustyle, meaning that the space between each column was two and a quarter times the diameter of the column, except for the two central columns at the front of the temple portico, which were three diameters apart.[1] The temple is constructed from septaria obtained from the Essex coast, possibly from near Walton-on-the-Naze, and large flint nodules, whilst the roof would have been of imbrex and tegula.[1] The columns are made from a core of curved brick, with the exterior and capitals rendered in plaster.[1] Polished marble, including Purbeck marble and rare giallo antico from Tunisia, and stone (including tufa from the Hampshire coast) would have faced the temple, large fragments of which have been found nearby.[1] Pieces of inscriptions on marble and large bronzed letters have been found around the site.[1] An altar stood in front of the podium of the temple.[1][3] The temple stood in the centre of a large precinct (temenos), parts of the wall of which are still visible beneath the later Norman castle bailey earthen bank.[4] In 2014 columns from the monumental façade of the precinct were discovered behind the High Street, with plans to make them visible to the public.[10] The entranceway to the precinct took the form of a tufa-faced 8-metre (26 ft) wide monumental arch flanked by a columned arcade screen.[1] Further excavations showed that the precinct was adorned with arcades and about 120 metres (390 ft) long.[11]

Boudican revolt and aftermath

In 60/1 AD the Iceni rebelled against the Romans, joined by the Trinovantes who were native to the area around Camulodunum.[1] As the symbol of Roman rule in Britain, the colonia of Camulodunum was the first target of the rebels, with its Temple seen in British eyes as the "arx aeternae dominationis" ("stronghold of everlasting domination") according to Tacitus.[4] The town was destroyed, with survivors taking refuge in the cella of the Temple, whose large bronze doors and strong, windowless chamber provided a safe haven.[1] However, the rebels laid siege to the Temple, which was stormed after two days. Tacitus wrote:

In the attack everything was broken down and burnt. The temple where the soldiers had congregated was besieged for two days and then sacked.[4]

The decapitated bronze head of a statue was found in the River Alde in Suffolk, and has been interpreted as having been taken from the Temple of Claudius by the Iceni. It has come to be identified as a bust of the Emperor Nero, who ruled during Boudica's rebellion.[1][12] The town and temple were rebuilt in the years after the attack, with the colonia reaching a peak of population in the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD.[1][3][4] The temple was one of the main public buildings in the town, and its façade and precinct were added to and enlarged over time.[1][3]

The temple in the Late Roman town

In contrast to the scaling down of private buildings in the town during the 4th century, there was an increase in the size and grandeur of public buildings in the period 275-400 AD.[3] The Temple of Claudius and its associated temenos buildings were reconstructed in the early 4th century, along with the possible forum-basilica building to the south of it.[1][3] The temple appears to have had a large apsidal hall built across the front of the podium steps, with numismatic dating evidence taking the date of the building up to at least 395 AD.[3] The changes to the temple in the 4th century may have been the result of the temple being converted to Christian use, as several Christian sites have been identified in the town from the Late Roman period,[3][13] and a Roman potsherd inscribed with a Chi Rho symbol was found at the site.[1]

Saxon and Norman periods

Large amounts of the superstructure of the temple were standing throughout the Saxon period,[1][4] when the temple was known as King Coel's Palace.[1][5] The medieval Colchester Chronicle states that the Norman architects of Colchester Castle built the structure on the remains of this "palace" in the years 1070–1080, with archaeological evidence showing that the base of the temple was used as the foundations of the castle.[1] Evidence has been uncovered from excavations in 2014 shows that the columns of the temple precinct entrance may also have been demolished in the Norman period to allow the building of the castle's bailey.[10] The podium was rediscovered in the 17th century when the underside of the temple's base was grubbed out, creating "vaults" under the castle.[1] The underside of the castle was not identified as the podium of the temple until archaeologist Mortimer Wheeler examined it in the early 20th century and found that the Norman builders had clasped the castle's walls to the Roman concrete podium.[1] Today the 17th-century "vaults" are open to visitors, showing the underside of the temple.[4]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 Crummy, Philip (1997) City of Victory; the story of Colchester - Britain's first Roman town. Published by Colchester Archaeological Trust (ISBN 1 897719 04 3)

- 1 2 "Temple of Claudius at Camulodunon (Colchester)". retrieved 27/07/2014

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Faulkner, Neil. (1994) Late Roman Colchester, In Oxford Journal of Archaeology 13(1)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Wilson, Roger J.A. (2002) A Guide to the Roman Remains in Britain (Fourth Edition). Published by Constable. (ISBN 1-84119-318-6)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Iron-Age and Roman Colchester | British History Online". www.british-history.ac.uk. Retrieved 27 July 2014.

- ↑ Crummy, Philip (1984) Colchester Archaeological Report 3: Excavations at Lion Walk, Balkerne Lane, and Middleborough, Colchester, Essex. Published by Colchester Archaeological Trust (ISBN 0-9503727-4-9)

- ↑ According to Tacitus the expenses for the temple's upkeep were among the cause of the Boudican Revolt: "delectique sacerdotes specie religionis omnes fortunas effundebant." i.e. "and the chosen priests wasted whole fortunes for the cult's sake." Annales 14.31

- ↑ Intro to Petronius – The Satyricon/Seneca – The Apocolocyntosis (1986) Published by Penguin Classics. (ISBN 0-14-044489-0)

- ↑ Apocolocyntosis - 8. "He wants to become a god: it's not enough that he has a temple in Britain, that the barbarians worship him and pray to him like to a god to obtain the benevolence of the idiot." - Original Latin+Greek: Deus fieri vult: parum est quod templum in Britannia habet, quod hunc barbari colunt et ut deum orant μωροῦ εὐιλὰτου τυχεῖν

- 1 2 "The Trust's investigation of Roman arcade in local press". www.thecolchesterarchaeologist.co.uk. Colchester Archaeological Trust. 25 July 2015. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- ↑ Remains of 'extraordinary' Roman arcade found in Colchester

- 1 2 "Bronze head of a Roman Emperor". British Museum.

- ↑ Crummy, Nina; Crummy, Philip; and Crossan, Carl (1993) Colchester Archaeological Report 9: Excavations of Roman and later cemeteries, churches and monastic sites in Colchester, 1971-88. Published by Colchester Archaeological Trust (ISBN 1-897719-01-9)

External links

- Colchester Temples at Roman-Britain.co.uk

- The Annals of Tacitus. Book 14, Chapter 31