Teng (Chinese: 螣; pinyin: téng; Wade–Giles: tʻêng) or Tengshe (simplified Chinese: 腾蛇; traditional Chinese: 騰蛇; pinyin: téngshé; Wade–Giles: tʻêng-shê; lit. 'soaring snake') is a flying dragon in Chinese mythology.

Names

This legendary creature's names include teng 螣 "a flying dragon" (or te 螣 "a plant pest") and tengshe 螣蛇 "flying-dragon snake" or 騰蛇 "soaring snake".

Teng

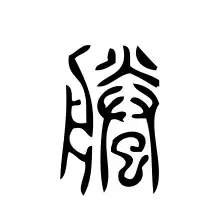

The Chinese character 螣 for teng or te graphically combines a phonetic element of zhen 朕 "I, we (only used by emperors)" with the "insect radical" 虫. This radical is typically used in characters for insects, worms, reptiles, and dragons (e.g., shen 蜃 "a sea-monster dragon" or jiao 蛟 "an aquatic dragon"). The earliest written form of teng 螣 is a (ca. 3rd century BCE) Seal script character written with the same radical and phonetic.

Teng 螣 has two etymologically cognate Chinese words written with this zhen 朕 phonetic and different radicals: teng 滕 (with the "water radical" 水) "gush up; inundate; Teng (state); a surname" and teng 騰 (with the "horse radical" 馬) "jump; gallop; prance; mount; ascend; fly swiftly upward; soar; rise". This latter teng, which is used to write the 騰蛇 tengshe flying dragon, occurs in draconic 4-character idioms such as longtenghuyue 龍騰虎躍 (lit. "dragon rising tiger leaping") "scene of bustling activity" and tengjiaoqifeng 騰蛟起鳳 ("rising dragon soaring phoenix", also reversible) "a rapidly rising talent; an exceptional literary/artistic talent; a genius".

The (3rd–2nd centuries BCE) Erya dictionary (16)[1] defines teng 螣 as tengshe 螣蛇 "teng-snake", and Guo Pu's commentary glosses it as a "[feilong 飛龍] flying dragon that drifts in the clouds and mist".

Some bilingual Chinese dictionaries translate teng as "wingless dragon", but this apparent ghost meaning is not found in monolingual Chinese sources. For instance, the Wiktionary and the Unihan Database translation equivalent for teng 螣 is "mythological wingless dragon of" [sic]. This dangling "of" appears to be copied from Robert Henry Mathews's dictionary[2] "A wingless dragon of the clouds", which adapted Herbert Giles's dictionary[3] "A wingless dragon which inhabits the clouds and is regarded as a creature of evil omen." While dragons are depicted as both winged and wingless (e.g., the lindworm "a bipedal wingless dragon"), Chinese dictionaries note teng "flying serpents" are wuzu 無足 "footless; legless" (see the Xunzi below) not "wingless".

Tengshe

"The teng 螣 dragon", says Carr, "had a semantically more transparent name of tengshe 騰蛇 'rising/ascending snake'." Tengshe is written with either teng 螣 "flying dragon" or teng 騰 "soaring; rising" and she 蛇 "snake; serpent".[1]

From the original "flying dragon; flying serpent" denotation, tengshe acquired three additional meanings: "an asterism" in Traditional Chinese star names, "a battle formation" in Chinese military history, and "lines above the mouth" in physiognomy.

First, Tengshe 螣蛇 Flying Serpent (or Tianshe 天蛇 "Heavenly Snake") is an asterism of 22 stars in the Chinese constellation Shi 室 Encampment, which is the northern 6th of the 7 Mansions in the Xuanwu 玄武 Black Tortoise constellation. These Tengshe stars spread across corresponding Western constellations of Andromeda, Lacerta, Cassiopeia, Cepheus, and Cygnus. In traditional Chinese art, Xuanwu is usually represented as a tortoise surrounded by a dragon or snake.

Second, Tengshe names "a battle formation". The (643–659 CE) Beishi history of Emperor Wencheng of Northern Wei Dynasty (r. 452–465 CE) describes a 454 CE battle. The Wei army routed enemy soldiers by deploying troops into over ten columns that changed between feilong "flying dragons", tengshe 螣蛇 "ascending snakes", and yuli 魚麗 "beautiful fishes" (alluding to Shijing 170).

Third, Tengshe "flying dragon" has a specialized meaning in Xiangshu 相術 "Chinese physiognomy", referring to "vertical lines rising from corners of the mouth".

Te

The earliest occurrence of 螣 means te "a plant pest" instead of teng "a flying dragon". The (ca. 6th century BCE) Shijing (212 大田) describes farmers removing plant pests called mingte 螟螣 and maozei 蟊賊 in fields of grain. These Shijing names rhyme, and Bernhard Karlgren reconstructed them as Old Chinese *d'ək 螣 and *dz'ək 賊. The Mao Commentary glosses four insects; the ming 螟 eats hearts, the te 螣 eats leaves, the mao 蟊 eats roots, and the zei 賊 eats joints. Compare these translations:

- We remove the insects that eat the heart and the leaf, And those that eat the roots and the joints[4]

- Avaunt, all earwigs and pests[5]

- We remove the noxious insects from the ears and leaves, and the grubs from roots and stems[6]

Han Dynasty Chinese dictionaries write te 螣 "a plant pest" with the variant Chinese character 蟘. The Erya defines ming 螟 as "[insect that] eats seedlings and cores" and te 蟘 "[insect that] eats leaves". Guo Pu's commentary glosses these four pests as types of huang 蝗 "locusts; grasshoppers". The (121 CE) Shuowen Jiezi dictionary defines ming "insect that eats grain leaves" and te as "insect that eats sprout leaves".

The identity of this rare te 螣 or 蟘 "a grain pest" called remains uncertain. In Modern Standard Chinese usage, te only occurs as a literary archaism, while ming is used in words like mingling 螟蛉 "corn earworm; adopted son" and mingchong 螟虫 "snout moth's larva".

Classical usages

Chinese classic texts frequently mention tengshe 螣蛇 or 騰蛇 "flying dragons". The examples below are roughly arranged in chronological order, although some heterogeneous texts are of uncertain dates. Only texts with English translations are cited, excluding tengshe occurrences in texts such as the Guiguzi, Shuoyuan, and Shiji.

Xunzi

The (c. 4th century BCE) Confucianist Xunzi (1 勸學) first records the Classical Chinese idiom tengshe wuzu er fei 螣蛇無足而飛 "flying dragon is without feet yet flies", which figuratively means "success results from concentrating on one's abilities".

Hanfeizi

The (3rd century BCE) Legalist text Hanfeizi uses tengshe 騰蛇 in two chapters.

"Ten Faults" (十過),[9] uses it describing the Yellow Emperor's heavenly music.

In by-gone days the Yellow Emperor once called a meeting of devils and spirits at the top of the Western T'ai Mountain, he rode in a divine carriage pulled by [龍] dragons, with Pi-fang a tree deity keeping pace with the linchpin, Ch'ih-yu [a war deity] marching in the front, Earl Wind [a wind deity] sweeping the dirt, Master Rain [a rain deity] sprinkling water on the road, tigers and wolves leading in the front, devils and spirits following from behind, rising serpents rolling on the ground, and male and female phoenixes flying over the top.

The "Critique on the Concept of Political Purchase" (難勢,[10] quotes Shen Dao contrasting feilong 飛龍 "flying dragon" with tengshe 螣蛇 to explain shi 勢 "political purchase; strategic advantage".

Shen Tzu said: "The flying dragon mounts the clouds and the t'eng snake wanders in the mists. But when the clouds dissipate and the mists clear, the dragon and the snake become the same as the earthworm and the large-winged black ant because they have lost that on which they ride. Where men of superior character are subjugated by inferior men, it is because their authority is lacking and their position is low. Where the inferior are subjugated by the superior, it is because the authority of the latter is considerable and their position is high.

Chuci

The (3rd–2nd centuries BCE) Chuci parallels tengshe 騰蛇 with feiju 飛駏 "flying horse" in the poem "A Road Beyond" (通路).[11]

With team of dragons I mount the heavens, In ivory chariot borne aloft. ... I wander through all the constellations; I roam about round the Northern Pole. My upper garment is of red stuff; Of green silk is my under-robe. I loosen my girdle and let my clothes flow freely; I stretch out my trusty Gan-jiang sword. The Leaping Serpent follows behind me, the Flying Horse trots at my side.

Huainanzi

The (2nd century BCE) Huainanzi uses both tengshe graphic variants 螣蛇 (with the insect radical, chapters 9 and 18, which is not translated) and 騰蛇 (horse radical, chapter 17).

"The Art of Rulership" (9 主術訓),[12] uses tengshe 螣蛇 with yinglong 應龍 "responding dragon". The t'eng snake springs up into the mist; the flying ying dragon ascends into the sky mounting the clouds; a monkey is nimble in the trees and a fish is agile in the water."

The "Discourse on Forests" (17) 說林訓,[1] has tengshe 騰蛇 in the same 遊霧 "drifts into the mist" phrase, "The ascending snake can drift in the mist, yet it is endangered by the centipede."

Other texts

Tengshe frequently occurs in Chinese poetry. Two early examples are "The Dark Warrior shrinks into his shell; The Leaping Serpent twists and coils itself" ("Rhapsody on Contemplating the Mystery" by Zhang Heng, 78–139 CE,[13]) and "Though winged serpents ride high on the mist, They turn to dust and ashes at last" ("Though the Tortoise Lives Long" by Cao Cao, 155–220 CE.[14])

Mythology

The Chinese books above repeatedly parallel the tengshe "soaring snake; flying dragon" with its near synonym feilong "flying dragon". Like the tianlong "heavenly dragon", these creatures are associated with clouds and rainfall, as Visser explains.

The Classics have taught us that the dragon is thunder, and at the same time that he is a water animal akin to the snake, sleeping in pools during winter and arising in spring. When autumn comes with its dry weather, the dragon descends and dives into the water to remain there till spring arrives again.[15]

The (1578 CE) Bencao Gangmu (43),[16] mentions this mythic serpent, "There are flying snakes without feet such as the 螣蛇 T'eng She." The commentary explains, "The t'eng-she changes into a dragon. This divine snake can ride upon the clouds and fly about over a thousand miles. If it is heard, (this means) pregnancy."[17]

Wolfram Eberhard surveys the cultural background of tengshe "ascending snake" myths.[18]

Frequently, in the early literature, the snake steps into the clouds [Shenzi, Baopuzi, Huainanzi]. Here one suspects that the word dragon was taboo and had to be substituted; this is confirmed by Chung-ch'ang T'ung [Hou Han Shu] stating that the ascending snake loses it scales. One can hardly speak of scales in the case of a real snake, but a dragon was believed to be scaly. Otherwise this flying snake may be compared with the folktale of the fight between centipede and snake which is associated with Thai culture … The dragon-like snake in the sky is again the dragon lung, again of the Thai cultures. Otherwise the "ascending snake" (t'eng-she) may mean a constellation of stars near the Milky Way [Xingjing]. According to Ko Hung [Baopuzi] it makes lightning, and this again equates it with the dragon lung.

Legends about flying snakes, serpents, and dragons are widespread in comparative mythology, exemplified by the Biblical Fiery flying serpent. Snakes in the genus Chrysopelea are commonly known as "flying snakes".

References

- Visser, Marinus Willern de (2008) [1913]. The Dragon in China and Japan. Introduction by Loren Coleman. Amsterdam - New York City: J. Müller - Cosimo Classics (reprint). ISBN 9781605204093. Internet Archive.

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 Tr. Carr, Michael (1990). "Chinese Dragon Names" (PDF). Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area. 13 (2): 87–189. p. 111.

- ↑ Mathews, Robert H., ed. 1931. Mathews' Chinese-English Dictionary. Presbyterian Mission Press. Rev. American ed. 1943. Harvard University Press. p. 894.

- ↑ Giles, Herbert A., ed. 1892. A Chinese-English Dictionary. Kelly & Walsh. 2nd. ed. 1912. p. 1352.

- ↑ F. Max Müller, ed. (1899). Sacred Books of the East. Volume 3. The Shû King (Classic of History) - The religious portions of the Shih King (Classic of Poetry) - The Hsiâo King (Classic of Filial Piety). Translated by Legge, James (2nd ed.). Clarendon Press. p. 372.

- ↑ The Book of Songs. Translated by Waley, Arthur. Grove. 1960 [1937]. p. 171.

- ↑ The Book of Odes. Translated by Karlgren, Bernhard. Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities. 1950. p. 166.

- ↑ Dubs, Homer, tr. 1928. The Works of Hsuntze, Translated from the Chinese, with Notes. Arthur Probsthain. p. 35.

- ↑ Knoblock, John, tr. 1988. Xunzi, A Translation and Study of the Complete Works, Volume 1, Books 1–6. Stanford University Press. p. 139.

- ↑ Tr. Liao, W.K. [Wenkui] (1939). The Complete Works of Han Fei Tzu. Arthur Probsthain. p. 77.

- ↑ Tr. Ames, Roger T. 1983. The Art of Rulership: A Study of Ancient Chinese Political Thought. University of Hawaii Press. p. 74.

- ↑ Hawkes, David, tr. 1985. The Songs of the South: An Anthology of Ancient Chinese Poems by Qu Yuan and Other Poets. Penguin. p. 271.

- ↑ Tr. Ames 1981, p. 176.

- ↑ Tr. Knechtges, David R. 1982. Wen Xuan, Or, Selections of Refined Literature. Cambridge University Press. p. 127.

- ↑ Tr. Ward, Jean Elizabeth. 2008. The Times of Lady Dai. Lulu. p. 19.

- ↑ Visser 1913, p. 109.

- ↑ Tr. Read, Bernard E. (1934). "Chinese Materia Medica VII; Dragons and Snakes". Peking Natural History Bulletin. Peking Society of Natural History: 349.

- ↑ Tr. Visser 1913, p. 75n2.

- ↑ Eberhard, Wolfram. 1968. The Local Cultures of South and East China. E. J. Brill. pp. 385-6.

External links

- 螣 entry, Chinese Etymology