The thanatotranscriptome denotes all RNA transcripts produced from the portions of the genome still active or awakened in the internal organs of a body following its death. It is relevant to the study of the biochemistry, microbiology, and biophysics of thanatology, in particular within forensic science. Some genes may continue to be expressed in cells for up to 48 hours after death, producing new mRNA. Certain genes that are generally inhibited since the end of fetal development may be expressed again at this time.[1][2][3]

Scientific history

Clues to the existence of a post-mortem transcriptome existed at least since the beginning of the 21st century,[4] but the word thanatotranscriptome (from (thanatos-, Greek for "death") seems to have been first used in the scientific literature by Javan et al. in 2015,[2] following the introduction of the concept of the human thanatomicrobiome in 2014 at the 66th Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Forensic Sciences in Seattle, Washington.[5]

In 2016, researchers at the University of Washington confirmed that up to 2 days (48 hours) after the death of mice and zebrafish, many genes still functioned.[1][3] Changes in the quantities of mRNA in the bodies of the dead animals proved that hundreds of genes with very different functions awoke just after death. The researchers detected 548 genes that awoke after death in zebrafish and 515 in laboratory mice. Among these were genes involved in development of the organism, including genes that are normally activated only in utero or in ovo (in the egg) during fetal development.

The thanatomicrobiome is characterized by a diverse assortment of microorganisms located in internal organs (brain, heart, liver, and spleen) and blood samples collected after a human dies. It is defined as the microbial community of internal body sites, created by a successional process whereby trillions of microorganisms populate, proliferate, and/or die within the dead body, resulting in temporal modifications in the community composition over time.

Thanatotranscriptomic analysis

Characterization and quantification of the transcriptome in a given "dead" tissue can identify genetic assets, which can be used to determine the regulatory mechanisms and set networks of gene expression.

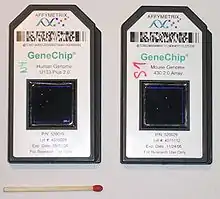

The techniques commonly used for simultaneously measuring the concentration of a large number of different types of mRNA include microarrays and high-throughput sequencing via RNA-Seq.

Analysis from a serology postmortem can characterize the transcriptome of a particular tissue cell type, or compare the transcriptomes between various experimental conditions. Such analysis can be complementary to the analysis of thanatomicrobiome to better understand the process of transformation of the necromass in the hours and days following death.[6]

Applications

Future applications of this information could include:

- Constructing a more accurate and nuanced definition of the phenomenon of "death".

- Helping forensic pathologists (or biologists or veterinarians) establish a more precise time of death (for example, in an eco-health investigation, when the practitioner needs information on the time or cause of poisoning, without a case of zoonosis). With a better understanding of the steps of this phenomenon in the human thanatomicrobiome, a coroner could, via a "postmortem serology",[7] establish with greater precision the time since death (by the hour, or even by the minute), which can be useful for investigations to reconstruct the conditions of death.[3]

- Illuminating the phenomena of cell death, apoptosis, and in particular the phenomenon of ischemia (including myocardial ischemia)[8] and the process of healing and resilience, perhaps even for the purpose of facilitating them. The post-mortem gene revival means that, for up to 48 hours following death, enough energy remains in the cells to activate some cellular machinery.[3] At least some of these genes appear to be those involved in physiological healing, or "auto-resuscitation".[3] Previous studies have shown that in people who have died by trauma, heart attack, or suffocation, various genes including those involved in cardiac muscle contraction and wound healing were active more than 12 hours after death.[8] Similar genetic evidence has been found in dental pulp.[9] Some authors in 2015 introduced the concept of "thanatotranscriptome apoptotic".[2]

- Understanding cancer. It has been found that genes involved in carcinogenesis are among those reactivated soon after death, with a peak of activity about 24 hours post-mortem.[3] A better understanding of this activity could shed light on the phenomenon of carcinogenesis and potentially lead to new tools to combat it.

- Improving the quality of organ transplants. The fact that cancer-related genes are activated following death can shed light on the timing of organ transplantation to reduce the incidence of cancer in transplant recipients.[3] Liver transplant recipients have been shown to be more prone to cancers after treatment than would be statistically normal. This phenomenon has been attributed to their post-operative diet, or to the immunosuppressive drugs administered to prevent their body from rejecting the transplant.[3] One hypothesis (yet to be verified) is that post-mortem cancer genes activated in the liver of the donor may also play a role.[3]

- Testing the hypothesis that after death, a rapid decrease of "suppressor gene" activity (which normally inhibit the activation of other genes, including those no longer needed after the fetal stage) would allow dormant genes wake up, at least for a short period of time.[3]

See also

References

- 1 2 Pozhitkov AE, Neme R, Domazet-Lošo T, Leroux BG, Soni S, Tautz D, Noble PA (January 2017). "Tracing the dynamics of gene transcripts after organismal death". Open Biology. 7 (1): 160267. doi:10.1098/rsob.160267. PMC 5303275. PMID 28123054.

- 1 2 3 Javan GT, Can I, Finley SJ, Soni S (December 2015). "The apoptotic thanatotranscriptome associated with the liver of cadavers". Forensic Science, Medicine, and Pathology. 11 (4): 509–516. doi:10.1007/s12024-015-9704-6. PMID 26318598. S2CID 21583165.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Williams A (21 June 2016). "Hundreds of genes seen sparking to life two days after death". New Scientist. Retrieved 6 March 2022.

- ↑ Vawter, Marquis P.; Evans, Simon; Choudary, Prabhakara; Tomita, Hiroaki; Meador-Woodruff, Jim; Molnar, Margherita; Li, Jun; Lopez, Juan F.; Myers, Rick; Cox, David; Watson, Stanley J.; Akil, Huda; Jones, Edward G.; Bunney, William E. (February 2004). "Gender-Specific Gene Expression in Post-Mortem Human Brain: Localization to Sex Chromosomes". Neuropsychopharmacology. 29 (2): 373–384. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1300337. ISSN 1740-634X. PMC 3130534. PMID 14583743.

- ↑ "Life After Human Death: The Thanatomicrobiome | American Academy of Forensic Sciences". www.aafs.org. 2014-12-31. Retrieved 2022-12-09.

- ↑ Javan GT, Finley SJ, Abidin Z, Mulle JG (2016-02-24). "The Thanatomicrobiome: A Missing Piece of the Microbial Puzzle of Death". Frontiers in Microbiology. 7: 225. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2016.00225. PMC 4764706. PMID 26941736.

- ↑ Moreno LI, Tate CM, Knott EL, McDaniel JE, Rogers SS, Koons BW, et al. (July 2012). "Determination of an effective housekeeping gene for the quantification of mRNA for forensic applications". Journal of Forensic Sciences. 57 (4): 1051–1058. doi:10.1111/j.1556-4029.2012.02086.x. PMID 22309221. S2CID 20576495.

- 1 2 González-Herrera L, Valenzuela A, Marchal JA, Lorente JA, Villanueva E (October 2013). "Studies on RNA integrity and gene expression in human myocardial tissue, pericardial fluid and blood, and its postmortem stability". Forensic Science International. 232 (1–3): 218–28. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2013.08.001. PMID 24053884.

- ↑ Poór VS, Lukács D, Nagy T, Rácz E, Sipos K (May 2016). "The rate of RNA degradation in human dental pulp reveals post-mortem interval". International Journal of Legal Medicine. 130 (3): 615–9. doi:10.1007/s00414-015-1295-y. PMID 26608472. S2CID 1155257.