In later Anglo-Saxon England, 10th to 11th centuries, a thegn (pronounced /θeɪn/) or thane[1] (or thayn in Shakespearean English) was an aristocrat who owned substantial land in one or more counties. Thanes ranked at the third level in lay society, below the king and ealdormen.[2] Thanage refers to the tenure by which lands were held by a thane as well as the rank.

The term thane was also used in early medieval Scandinavia for a class of retainers, and thane was a title given to local royal officials in medieval eastern Scotland, equivalent in rank to the child of an earl.

Etymology

|

| Cyning (sovereign) |

| Ætheling (prince) |

| Ealdorman (Earl) |

| Hold / High-reeve |

| Thegn |

| Thingmen / housecarl (retainer) |

| Reeve / Verderer (bailiff) |

| Churl (free tenant) |

| Villein (serf) |

| Cottar (cottager) |

| Þēow (slave) |

The Old English þeġ(e)n (IPA: [ˈθej(e)n], "man, attendant, retainer") is cognate with Old High German degan and Old Norse þegn ("thane, franklin, freeman, man").[3]

The thane had a military significance, and its usual Latin translation was miles, meaning soldier, although minister was often used. An Anglo-Saxon Dictionary describes a thane as "one engaged in a king's or a queen's service, whether in the household or in the country". It adds: "the word... seems gradually to acquire a technical meaning... denoting a class, containing several degrees".[4]

Origins

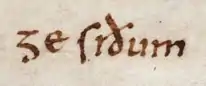

By the eighth century, the common term for a noble was gesith. There were both land-owning and landless gesiths.[5] A landless gesith would serve as a retainer in the comitatus of a king, queen, or lord (Old English: hlaford, literally "bread-giver"). In return, they were provided protection (Old English: mund) and gifts of gold and silver. Young nobles were raised with the children of kings to someday become their gesith.[6] A gesith might be granted an estate in reward for loyal service.[7]

In the tenth century, the word gesith was replaced with the word thegn.[7] Thegn is only used once in the laws before the time of Aethelstan (c. 895–940), but more frequently in the charters.[4] Apparently unconnected to the German and Dutch word dienen, or serve, H. M. Chadwick suggests "the sense of subordination must have been inherent... from the earliest time".[8] It gradually expanded in meaning and use, to denote a member of a territorial nobility, while thegnhood was attainable by fulfilling certain conditions.[4]

The nobility of pre-conquest England was ranked according to the heriot paid in the following order: earl, king's thegn, median thegn. In Anglo-Saxon society, king's thegns attended the king in person, bringing their own attendants and resources. A "median thegn" did not hold land directly from the king, but through an intermediary lord.

Status

The thegn was of higher status than the ceorl. Chadwick states that "from the time of Æthelstan, the distinction between thegn and ceorl was the broad line of demarcation between the classes of society". The relative status was reflected in the level of weregild provided by the thegn, generally fixed at 1,200 shillings, or six times that of the ceorl. The thegn was the twelfhynde man of the laws, as distinct from the twyhynde man, or ceorl.[4]

While some inherited the rank of thegn, others acquired it through property ownership or wealth. The Geþyncðo stated, "And if a ceorl throve, so that he had fully five hides of his own land, church and kitchen, bellhouse and burh-gate-seat, and special duty in the king's hail, then was he thenceforth of thegn-right worthy." This also applied to merchants who "fared thrice over the wide sea by his own means."[9] In the same way, a successful thegn might hope to become an earl.[4]

Eventually, the increase in the number of thegns produced a subdivision of the order. There arose a class of king's thegns corresponding to the earlier thegns and a larger class of inferior thegns including some who were the thegns of bishops or of other thegns. The king's thegns had special privileges and only the king had jurisdiction over his thegns. In Latin, king's thegn was translated as comes ("count").[10] In the law of Cnut, a king's thegns paid a larger heriot than ordinary thegns.[4]

The distinction between the ordinary thegns and the king's thegns, or those of the first class, has been defined by folklorist Sir George Laurence Gomme as "a Baron, or petty Prince, ruling under the Sovereign".[11] This is analogous to the evolution of a warlord's henchman to vassal (one of Charlemagne's great companions).

In the Domesday Book, Old English þegn has become tainus in the Latin form, but the word does not imply high status. Domesday Book lists the taini who hold lands directly from the king at the end of their respective counties, but the term became devalued, perhaps partly as the number of thegns increased.

Although their exact role is unclear, the twelve senior thegns of the hundred played a part in the development of the English system of justice. Under a law of Aethelred they "seem to have acted as the judicial committee of the court for the purposes of accusation".[12] This suggests some connection with the modern jury trial.

Post-conquest England

After the Norman conquest of England in 1066, William the Conqueror replaced the Anglo-Saxon aristocracy with Normans, who replaced the previous terminology with their own names for such social ranks. Those previously known as thegns became part of the knightly class.[4]

Runestones

During the later part of the tenth and in the eleventh centuries in Denmark and Sweden, it became common for families or comrades to raise memorial runestones. Approximately fifty of these note that the deceased was a thegn. Examples of such runestones include Sö 170 at Nälberga, Vg 59 at Norra Härene, Vg 150 at Velanda, DR 143 at Gunderup, DR 209 at Glavendrup, and DR 277 at Rydsgård.

See also

References

Citations

- ↑ "Thane" Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 25 July 2023.

- ↑ Keynes 2014, pp. 459–461.

- ↑ Northvegr – Zoëga's A Concise Dictionary of Old Icelandic

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Holland 1911, p. 743.

- ↑ Loyn 1955, pp. 530 & 532.

- ↑ Jolliffe 1961, p. 14–15.

- 1 2 Loyn 1955, p. 530.

- ↑ Chadwick 1905, pp. 84–85.

- ↑ Stubbs 1895, p. 65.

- ↑ Britannica 1998.

- ↑ Gomme 1886, p. 296.

- ↑ Holdsworth 1903, p. 7.

Sources

- Chadwick, Hector Munro (1905). Studies on Anglo-Saxon Institutions. Cambridge University Press.

- Gomme, Laurence (1886). Dialect, Proverbs and Word-lore. Elliott Stock.

- Holdsworth, William Searle (1903). A History of English Law. Vol. 1. London: Methuen & Co.

- Holland, Arthur William (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 26 (11th ed.). p. 743.

- Jolliffe, J. E. A. (1961). The Constitutional History of Medieval England from the English Settlement to 1485 (4th ed.). Adams and Charles Black.

- Keynes, Simon (2014). "Thegn". In Lapidge, Michael; Blair, John; Keynes, Simon; Scragg, Donald (eds.). The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Anglo-Saxon England (2nd ed.). Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley Blackwell. pp. 459–461. ISBN 978-0-470-65632-7.

- Loyn, HR (1955). "Gesiths and Thegns in Anglo-Saxon England from the Seventh to Tenth Century". The English Historical Review. 70 (277): 529–549. doi:10.1093/ehr/LXX.CCLXXVII.529. JSTOR 558038.

- Stubbs, William (1895). Select Charters and Other Illustrations of English Constitutional History, from the Earliest Times to the Reign of Edward the First (8th ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- "Thane". Encyclopedia Britannica. 20 July 1998.

Further reading

- Stubbs, William (1874). The Constitutional History of England, in Its Origin and Development. Vol. 1. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 149–158.

- Sukhino-Khomenko, Denis. "Thegns in the Social Order of Anglo-Saxon England and Viking-Age Scandinavia: Outlines of a Methodological Reassessment." Interdisciplinary and Comparative Methodologies 14 (2019): 25-50.