| The Ascent | |

|---|---|

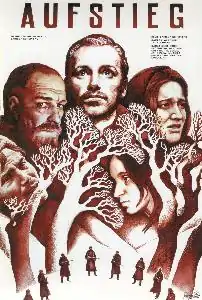

German poster - (left to right) Rybak, the village headman, Sotnikov, Basya, Demchikha | |

| Russian | Восхождение |

| Directed by | Larisa Shepitko |

| Written by | Vasil Bykaŭ (novel) Yuri Klepikov Larisa Shepitko |

| Based on | Sotnikov by Vasil Bykaŭ |

| Starring | Boris Plotnikov Vladimir Gostyukhin Sergei Yakovlev Lyudmila Polyakova Anatoli Solonitsyn |

| Cinematography | Vladimir Chukhnov Pavel Lebeshev |

| Music by | Alfred Schnittke |

Production company | |

Release date |

|

Running time | 111 minutes |

| Country | Soviet Union |

| Languages | Russian German |

The Ascent (Russian: Восхождение, tr. Voskhozhdeniye, literally - The Ascension) is a 1977 black-and-white Soviet drama film directed by Larisa Shepitko and made at Mosfilm.[1] The film was shot in January 1974 near Murom, Vladimir Oblast, Russia, in appalling winter conditions, as required by the script, based on the 1970 novel Sotnikov by Vasil Bykaŭ.[2] It was Shepitko's last film before her death in a car accident in 1979. The film won the Golden Bear award at the 27th Berlin International Film Festival in 1977.[3] It was also selected as the Soviet entry for the Best Foreign Language Film at the 50th Academy Awards, but was not accepted as a nominee.[4]

Plot

During the Great Patriotic War (World War II), two Soviet partisans, Sotnikov (Boris Plotnikov) and Rybak (Vladimir Gostyukhin) go to a Belarusian village in search of food. After taking a farm animal from the collaborationist headman (Sergei Yakovlev), they head back to their unit, but are spotted by a German patrol. After a protracted gunfight in the snow in which one of the Germans is killed, the two men get away, but Sotnikov is shot in the leg. Rybak has to take him to the nearest shelter, the home of Demchikha (Lyudmila Polyakova), the mother of three young children. However, they are discovered and captured.

The two men and a sobbing Demchikha are taken to the German headquarters. Sotnikov is interrogated first by local collaborator Portnov (Anatoli Solonitsyn), a former Soviet club-house director and children's choirmaster who became the local head of the Belarusian Auxiliary Police, loyal to the Germans. When Sotnikov refuses to answer Portnov's questions, he is brutally tortured by members of the collaborationist police, but gives up no information. However, Rybak tells as much as he thinks the police already know, hoping to live so he can escape later. Portnov offers him the job of policeman. Afterwards, they are imprisoned in the same cellar for the night with the headman, now suspected of supporting the partisans, Basya Meyer, a young Jewish girl hidden by one of the village members, and Demchikha. Sotnikov agrees to speak with Portnov the next day and shoulder all responsibility, hopefully absolving the others.

The next morning, all are led out of the cellar, with Sotnikov demanding to speak to Portnov, who brushes him off after an impassioned plea. Desperate, Rybak begs with Portnov to let him join the police, who allows it. Seeing this, Demchikha attempts to reveal who was hiding Basya but to no avail. Sotnikov and the others are led away and hanged.

As he heads back to the camp with his new comrades, Rybak is vilified by the villagers. With his guilt and lack of courage to escape, he tries to hang himself in the outhouse with his belt, but fails. A fellow policeman calls for Rybak until Rybak opens the door. The policeman tells him that their commander wants him and leaves him alone in the courtyard. Rybak stares out the open door and begins to laugh and weep.

Cast

- Boris Plotnikov as Sotnikov

- Vladimir Gostyukhin as Rybak

- Sergei Yakovlev as Village elder

- Lyudmila Polyakova as Demchikha

- Viktoriya Goldentul as Basya Meyer

- Anatoli Solonitsyn as Portnov, the collaborationist interrogator

- Maria Vinogradova as Village elder's wife

- Nikolai Sektimenko as Stas'

Production

Pre-production

All motion pictures are personal but the desire to film The Ascent was almost a physical need. If I had not shot this picture it would have been a catastrophe for me. I could not find any other material with which I could transmit my views on life, on the meaning of life.

— Larisa Shepitko [5]

Before The Ascent, the director Larisa Shepitko shot the film You and Me. Production took place under an atmosphere of severe stress. Technical and organizational difficulties led to the necessity of calling an ambulance for the director's health. The release of the film was not any easier; the censors deleted critical scenes and Shepitko had to fight for every single one of them. This struggle was not always successful. Despite the fact that the film was one of the prize winners at the Venice Film Festival, the removed scenes were a terrible blow to Shepitko, who believed that changing an important moment leads to the loss of main ideas.[6]

For Shepitko it was a difficult time after the film's release. By her own admission, for a period of four months the director was in "a monstrous mental and physical exhaustion." The realization of what was subsequently necessary came to her suddenly while she was recuperating at a Sochi sanatorium, but her creative plans were undermined by a disastrous fall, which resulted in a serious concussion and a spinal injury. For a few weeks Shepitko was confined to bed. The situation was also aggravated by the fact that she was pregnant, but she felt that during her pregnancy she came to understand the complexities of life more fully. Every day she was haunted by the possibility of death; reading the novel Sotnikov by Vasil Býkaŭ during this period helped Shepitko express this state on the silver screen.[6]

Screenplay

For the most part the screenplay written by Yuri Klepikov follows the novel. Shepitko turned to Klepikov on the recommendation of her classmate Natalya Ryazantseva but he was already busy working on another script. Klepikov did not refuse the commission, but he asked to postpone working on The Ascent for a week. Shepitko urged him to start work immediately and a single telephone conversation with her convinced him to drop everything he was doing. Klepikov, by his own admission, "could not withstand the energy of the typhoon whose name was Larisa," and started the task of revising the literary foundation which he later described as "a piping philosophical parable which combined the high spirit of man with his obvious desire to keep the body as a receptacle of the spirit."[7] The result of the work became a 70-page script that Shepitko then meticulously edited.[7][8] Shepitko practised the "engineer's" approach: she did not tolerate uncertainty or haziness in work and did not rely on director's improvisation or creative inspiration. Every frame, every remark, every scene was carefully checked and planned in advance. According to Yuri Klepikov even "the fruitful spontaneity was due to the very environment of the shoot," which was ensured by the carefully crafted script.[9]

When adapting the script from Sotnikov the main concern of the director was not to lose the deeper philosophical content of the story. While the literary work by Býkaŭ was full of sensual details like "icy cold", "famine", "danger", Shepitko strongly discouraged attempts to be satisfied with external action and demanded an "internal justification" of each movement, gesture and glance of the heroes. In order to express the spiritual states she often had to deviate from the literary basis. For example, in the finale of the original story Rybak decides to hang himself in the latrine but discovers that he forgot to ask for the belt back which had been taken by the policemen an evening before. Theoretically, the film could portray the absence of the belt, but then - according to the writers - the scene would be limited to the designation of the circumstances: informative but unimpressive denial in terms of the artistic sense. The authors "returned" the belt to Rybak but he was deprived of the ability to hang himself; implying that even death refuses a traitor. Their idea was to leave Rybak alone with the knowledge of his fall. The following long close-up of majestic nature signified the freedom which Rybak desperately desires and was intended to emphasize the utmost despair "of a person who lost himself."[10]

Shepitko's husband Elem Klimov suggested the film's title. Long before, in 1963, a tradition was established between the future spouses that for a good idea they would receive ten roubles. When they just started dating, Klimov came up with the name for Shepitko's thesis film – Heat. Shepitko and Klimov decided to continue this playful approach of rewarding each other but after all the years of their union Klimov alone received the ten rouble reward and only twice: for Heat and for The Ascent.[11]

Beginning of production

The next step was the need for the script's approval from the State Committee for Cinematography. By that time Shepitko had already gained a reputation of an inconvenient director. In 1973, when she raised the topic of making the film, the answer from an official of the State Committee for Cinematography was a firm negative.[12] The director did not spark a confrontation but she also did not offer any other projects.[6] Throughout her directing career, Shepitko only started working on a film if she felt that "if she does not do it, then she dies."[13]

For help in overcoming the resistance of the authorities and the State Political Directorate, Shepitko turned to Gemma Firsova with whom she had studied at VGIK. Firsova was an administrator of an association of military-patriotic films. She was affected much more by the script than by the novel and the day she met Shepitko, she went to meet the Minister of Cinematography Philippe Ermash. In a conversation with Ermash's replacement (in her memoirs Firsova did not call Boris Pavlenok by his name), Firsova said that she took the script under her responsibility, with a lie that "everything will be fine with the State Political Directorate." Ermash's replacement reacted skeptically to the pleas, and the subsequent process from script approval to acceptance of the film's actors was accompanied by considerable difficulties. The main accusation was that Shepitko allegedly made a religious parable with a mystical tone from the partisan story; this was considered an insurrection in the atheistic Soviet cinema.[12] Shepitko retorted that she was not religious and that a story about betrayal was antediluvian. According to her, Judas and Jesus had always existed and that if the legend connected with people then this means that it was alive in every person.[6] Officials met Schnittke's score with resistance and they ordered that the allusions to biblical texts be removed.[14]

From the moment she read the story Sotnikov, it took Larisa Shepitko four years to prepare and to obtain permits from the authorities to begin shooting the picture.[15]

Casting

Shepitko decided to use unknown or little-known actors whose past roles would not cast a shadow on their characters in The Ascent. Because of this, she rejected Andrey Myagkov, who wanted to act in the picture. The same fate befell Nikolai Gubenko. Vladimir Vysotsky, who yearned to play Rybakov, also did not pass selection. At the time when the castings for The Ascent were taking place, Vysotsky was starring in the film The Negro of Peter the Great. Production of that film took place at the Mosfilm sound stage, adjacent to where the auditions were being held, and during his breaks Vysotsky often went to see what was happening at Shepitko's sound stage.[16]

From the beginning of the search for the actor who would play Sotnikov, Larisa Shepitko instructed Emma Baskakova, her casting assistant, to keep in mind the image of Christ, although it was impossible to mention this out loud.[6] Boris Plotnikov, a 25-year-old actor of the Sverdlovsk Theater, turned out to be the best candidate for the role according to the director, but the officials of Goskino saw in Shepitko's plan the intention to put Jesus on to the Soviet screen. Plotnikov, whose repertoire until then largely included the roles of magical animals,[17] even had to be made up for the purpose of greater glorification of the character so that the artistic council would approve him for the role. The actor went through seven test shots altogether for which he always had to fly to Moscow from Sverdlovsk.[18]

For the role of Rybak the director screened 20 candidates. The actor chosen for the role was the unknown actor Vladimir Gostyukhin.[8] Gostyukhin, who had worked for six years in the Soviet Army theater as a furniture and prop maker, had once replaced a sick actor in the play Unknown Soldier. His performance was noticed by Svetlana Klimova, who was the second unit director for Vasiliy Ordynski. Gostyukhin received an invitation to act in the series The Road to Calvary, where he played the role of the anarchist and bandit Krasilnikov for whom charisma and a strong temperament were required. It was while working that set that he was noticed by Larisa Shepitko's assistants. Gostyukhin was invited to audition for the role of Rybak, but initially could not equate "a woman of great beauty [Sheptiko] with the super-masculine, tough and tragic story by Vasil Býkaŭ." But after a 20-minute conversation with the director, he was convinced that only she could film the adaptation of this weighty book. Even so, Shepitko initially had doubts about the candidate, who even with his actor's training, was still only a stage laborer. Plotnikov had immediately attracted the director with his constitution, smile, look and plasticity while Gostyukhin's appearance did not coincide with how Shepitko saw Rybak: the young actor came to his audition with "frivolous" bangs which were uncharacteristic for a partisan. Gostyukhin's rude manners initially alienated other members of the selection committee but Shepitko explained away his behavior as shyness and decided to audition the candidate who had already at the first rehearsal made a strong impression on everyone with his dedication in realizing the character.[16][17]

The actor for the role of Portnov was selected based on the image of Sotnikov. Larisa Shepitko wanted to find someone similar in external characteristics to Plotnikov, saying, "They are similar, but Portnov is an antipode to Sotnikov based on internal beliefs. This should be a very good actor. Their duel, yes, yes, the fight with Sotnikov - the eternal conflict, the everlasting battle between spirit and lack of spirituality ... Dying, suffering Sotnikov wins because he is strong in spirit. He dies and rises above his tormentor."

Anatoly Solonitsyn at first did not see anything interesting in what he thought of as a "supporting role", and which he considered a "rehash" of what had been filmed earlier. Initially, the actor did not even understand what was wanted of him despite the fact that he diligently played the "enemy," a "man with a bruised heart," or a "man without a future" as was required. But he felt that the character would turn out to be little but a caricature, as in cheap popular literature.[19] Only a long conversation with the director allowed him to understand her vision of Portnov: the personification of the negative side in the eternal history of man's struggle with the animal inside himself in the name of the supreme value – namely, the value of the spirit. The director insisted that the Great Patriotic War was won by the Soviet people because of their high level of awareness, so Portnov's "anti-hero" role was especially important because the character was supposed to emphasize the superiority of the human spirit's power over matter.[6]

Filming

Filming began on Jan. 6, 1974 – the birthday of the director Shepitko (according to other sources filming began on January 5[20]) - in the vicinity of the town of Murom. The first scenes were shot on location in the middle of fields, forests and ravines despite the fact that the weather was forty degrees below zero. According to Boris Plotnikov the frost and the virginal snow were mandatory conditions which Vasil Býkaŭ had set out in his story.[18] This approach was endorsed by Larisa Shepitko, according to whom the actors had to "feel the winter all the way down to their very cells" for a more reliable way of entering the character.[6] Together with this, the filming process was planned in such a way that the actors started with the easiest acting in the psychological sense, and scenes which allowed them to gradually sink into their characters.[21]

From the outset Shepitko managed to inspire every co-worker with her idea; they understood the film to be about sacred things: motherland, higher values, conscience, duty and spiritual heroism. Her ability to enthrall her colleagues had already manifested before: Yuri Vizbor (lead actor in the movie You and Me) said: "We worked for Larisa, specifically, personally for her. She had faith and that was the reason. Faith in goodness and the need for our work, and it is this faith that was absolutely a material substance, which can be very real to rely on."

In the harsh conditions in which the shoot took place, this factor was very important: extras and crew members were frostbitten, but no one complained. Shepitko herself did not ask for or require special treatment and her colleagues remembered her as an example of courage, faith, patience, and extraordinary care. For example, Boris Plotnikov was dressed very lightly and quickly grew numb from the cold and the piercing winds in the open field; but after the command "Stop! Cut!" the director came over to him to warm him up and to thank him. She also had to warm up Vladimir Gostyukhin who later wrote: "It was worth it “to die” in the scene to be able to feel her gratitude." He said that almost no one knew what effort Shepitko gave when shooting each frame. Sometimes Gostyukhin had to carry the director from the car to the hotel room by himself: Shepitko was sometimes not very physically well and occasionally her strength weakened. Long before The Ascent, Shepitko became ill with hepatitis on the set of the movie Heat. Ignoring advice to go to Moscow, she went on to shoot the picture from a stretcher on which she was brought from the infectious barracks.[22] Moreover, Shepitko did not recuperate enough, and the consequences of the disease adversely affected her well-being in the future, in particular on the set of The Ascent. In addition she experienced extreme pain which was caused by her recent spinal trauma. But Shepitko still rose two to three hours before the crew to have time to prepare, after which she worked to the maximum limit of her capabilities throughout the day. For example, in one long scene, the partisans are running away with difficulty through the thick snow from their pursuers. On screen it was necessary to show the deadly fatigue of the flushed, panting people. To prevent hypocrisy in the scenes, the director ran alongside the actors while filming, experiencing their exhausted state with them.[15] With this dedication the shooting took place without interruption and was completed one month ahead of schedule.[18]

In order to achieve the desired performance from the actors, Shepitko sometimes talked for a long time with them out in the cold. For example, despite the crew's full readiness, the director would talk for a long time with Boris Plotnikov, whose character she carefully directed during the filming. Shepitko's habit of clearly stating her thoughts contributed to a successful transmission of information; she did not use abstruse terms that might mask the lack of clarity. [23] She waited for the necessary expression of emotion, for the right facial expression and gestures and then suddenly would give the order to start filming. Boris Plotnikov later said that he would have liked to repeat this experience in other films, but never did. On working with Shepitko, Plotnikov spoke of "a meeting with a living genius." Vasil Býkaŭ also shared a similar opinion about the film's director, he called her "Dostoevsky in a skirt." Býkaŭ valued Larisa Shepitko very highly and once admitted that had he met her before, he would have written Sotnikov differently.[18]

Vladimir Gostyukhin described the filming process not as acting but as "death in every frame." For him and Plotnikov it was extremely important to validate the director's trust, since she had needed to defend their casting choices long and hard in front of the Soviet film authorities. Gostyukhin spoke of Shepitko's ability to convey an idea to the actors, akin to hypnosis, under which he with Plotnikov - the newcomers to the film studio - could produce the "miracle of transformation." During the first rehearsal Shepitko even sprayed their faces with snow. By the latter's suggestion it was done to collect their attention and will and also to give texture and credibility to their characters. Later it became a kind of ritual, often preceding the next take on the film set.[15] Gostyukhin recalled that he transformed into Rybak to such a degree that even the made-up bruise only fell from his face after three weeks. After the film was shot the actor tried for such a long time to leave his role behind and to become himself again that he refused to star in Shepitko's next planned film, entitled Farewell, despite her persistent requests.[16]

The production designer Yuriy Raksha later spoke about the situation as follows:

We started to work and began our unique existence along with the characters. I can say that the film matured us too. Speaking about the holy things, about categories of high spirituality, we were obligated to apply high standards to ourselves too. It was impossible to be one person on the set and to be another one in real life.

Release

The film was nearly banned: regulatory authorities believed that a "religious parable with a mystical tinge" was shot instead of a partisan story. The chances were very high that the film would be shelved, until Elem Klimov (the husband of Larisa Shepitko and also a film director by profession) decided to take a desperate step. While Klimov was preparing for the shooting of the film Kill Hitler (which was released under the title of Come and See in 1985), he met with Pyotr Masherov, the first secretary of the Communist Party of Belarus, who strongly supported the director and even acted as a historical consultant. During the war, the senior official was himself a partisan and moreover in 1942 the German occupiers hanged his mother for collaborating with the partisans.[6][22]

When Klimov, bypassing Mosfilm, invited Masherov to a special preview of The Ascent, Masherov initially was skeptical and was expecting to see "effeminate directorial work." The still somewhat wet film was brought to Minsk directly from the lab, and Larisa Shepitko herself sat at the mixing console .[24] Twenty or thirty minutes after Masherov had started watching, he found he could not tear himself away from the screen, and by the middle of the movie he was crying, without hiding away from the republic's leaders who were present in the hall. At the end of the film, Masherov - contrary to tradition (usually at such premieres opinions were heard first from the lower ranks and then from the highest) - came on stage and spoke for about forty minutes. His words were not recorded by anyone but Elem Klimov testified to his wife that his excited speech was one of the best he ever heard addressed. The Belarusian writer and veteran of the Great Patriotic War Ales Adamovich, who was present at the screening, described Masherov as someone who questioned, "Where did this girl come from, who of course experienced nothing of the sort, but knows all about it, how could she express it like this?"[25] After a few days, The Ascent was formally accepted without any amendments.[6][22]

In July 2018, it was selected for screening in the Venice Classics section at the 75th Venice International Film Festival.[26]

The film was first released on North American home video in a boxed DVD set by The Criterion Collection in 2008 through its Eclipse series, where it was paired with Wings. [27] Criterion later released it on Blu-ray in 2021. [28]

See also

References

- ↑ Peter Rollberg (2016). Historical Dictionary of Russian and Soviet Cinema. US: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 65–66. ISBN 978-1442268425.

- ↑ И жизнь, и слезы, и любовь. Bulvar magazine. 3 January 2013. Retrieved 22 May 2015.

- ↑ "Berlinale 1977 - Filmdatenblatt". Archiv der Internationale Filmfestspiele in Berlin. 1977. Retrieved 2010-02-27.

- ↑ Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences

- ↑ Klimov 1987.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Валентина Хованская. Лариса. Воспоминания о работе с Ларисой Шепитько (in Russian). Archived from the original on 2015-04-19. Retrieved 2013-05-30.

- 1 2 Klimov 1987, p. 93.

- 1 2 Восхождение (1976) (in Russian). Энциклопедия отечественного кино.

- ↑ Klimov 1987, pp. 94–95.

- ↑ Klimov 1987, p. 94.

- ↑ Klimov 1987, p. 18.

- 1 2 Гибель режиссёра Ларисы Шепитько (in Russian). Официальный сайт Льва Дурова. Archived from the original on 2013-06-22. Retrieved 2013-05-31.

- ↑ Марина Базавлук. Восхождение (in Russian). История кино. Archived from the original on 2012-12-11. Retrieved 2013-05-31.

- ↑ Gemma Firsova (December 2006). Предупреждение. О Ларисе Шепитько (in Russian). Искусство кино. Archived from the original on 2013-03-17. Retrieved 2013-05-31.

- 1 2 3 Владимир Гостюхин (записал Ю. Коршак). Снегом обожженное лицо (in Russian). История кино. Archived from the original on 2012-12-11. Retrieved 2013-06-07.

- 1 2 3 Анжелика Заозерская (2011-07-21). Актёр Владимир Гостюхин: Самая ранимая и зависимая – это профессия артиста (in Russian). Театрал. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2013-06-04.

- 1 2 Юрий Тюрин. Владимир Гостюхин. Творческая биография (in Russian). Русское кино. Archived from the original on 2013-04-26. Retrieved 2013-06-04.

- 1 2 3 4 И жизнь, и слёзы, и любовь (in Russian). Бульвар Гордона. 2013-01-13. Archived from the original on 2013-06-27. Retrieved 2013-05-31.

- ↑ Klimov 1987, pp. 62–63.

- ↑ Klimov 1987, p. 50.

- ↑ Klimov 1987, p. 51.

- 1 2 3 Ивойлова И. (2003). Восхождение (in Russian). М.: Труд.

- ↑ Klimov 1987, p. 41.

- ↑ Klimov 1987, p. 12.

- ↑ Klimov 1987, p. 15.

- ↑ "Biennale Cinema 2018, Venice Classics". labiennale.org. 13 July 2018. Retrieved 22 July 2018.

- ↑ "Eclipse Series 11: Larisa Shepitko". The Criterion Collection. Retrieved 2023-04-24.

- ↑ "The Ascent". The Criterion Collection. Retrieved 2023-04-24.

Literature

- Klimov, Elem (1987). Лариса: книга о Ларисе Шепитько [Larisa: book about Larisa Shepitko] (in Russian). Moscow: Iskusstvo. p. 290.

- Klimov, Hermann; Murzina, Marina; Plahov, Andrei; Fomina, Raisa (2008). Элем Климов. Неснятое кино [Elem Klimov. Unshot cinema] (in Russian). Moscow: Chroniqueur. p. 384. ISBN 978-5-901238-52-3.

External links

- The Ascent at IMDb

- The Ascent at AllMovie

- The Ascent at Turner Classic Movies

- The Ascent at the official Mosfilm site with English subtitles

- The Ascent: Out in the Cold an essay by Fanny Howe at the Criterion Collection