| |

| Author | Louise Erdrich |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Series | "The Birchbark House Series" |

Publication date | 1999 |

Published in English | 1999 |

| Followed by | The Game of Silence (2006) The Porcupine Year (2008) Chickadee(2012) Makoons (2016) |

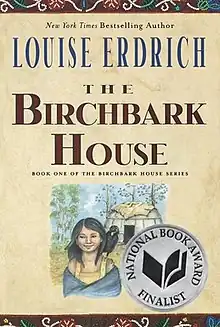

The Birchbark House is a 1999 indigenous juvenile realistic fiction novel by Louise Erdrich, and is the first book in a five book series known as The Birchbark series. The story follows the life of Omakayas and her Ojibwe community beginning in 1847 near present-day Lake Superior. The Birchbark House has received positive reviews and was a 1999 National Book Award Finalist for young people's fiction.[1]

After the prologue, the novel continues through the eyes of a seven-year-old young girl, Omakayas ("her name means "little frog" because her first step was a hop). The circular motion of the Ojibwa culture is represented through the motions of the four seasons, Neebin (summer), Dagwaging (fall). Biboon (winter), and Zeegwun (spring). The community works together to hunt, build, gather, and survive according to the needs of the tribe according to each season. Omakayas cares for her family because she knew that with the winter comes a smallpox epidemic. She learns about her connection to all nature, and discovers her gift of dreams. The most important thing Omakayas learns about herself is why she didn't get smallpox when most everyone in the community did. She has three siblings: a baby named Neewo (who dies from smallpox), Little Pinch (later changed to Big Pinch) and Angeline.

The novel includes decorative pencil drawings, as well as a map of the Ojibwa community, and a glossary of Ojibwa language translations.[2]

Background

The Birchbark House originally began as a story Erdrich would tell her daughters. Erdrich was also moved to write The Birchbark House to show aspects of a real native family during that time in history. The popular media that existed at the time of her writing often portrayed Native Americans in a negative light, e.g. the racism against natives in Little House on the Prairie. Erdrich wanted to counter this narrative by sharing her own version of these stories. As a child, Erdrich frequently visited Madeline Island, where her family originated.[3] Because of this familiarity, Erdrich chose to set her novel in this part region, telling the story of her family’s people, the Turtle Mountain Chippewa.[4] She hoped that in telling this story she could deepen the understanding that the public had of Native Americans, saying that ”there's this humanity that's been lost in the public perception about Native American people.”[3] The series reinforces the deeper emotional aspects of the Ojibwe, and reminds the reader of their prevailing lineage.[5]

Erdrich's larger vision was to give readers a more in depth look into native families. She wanted to make accessing real native lives easier giving children a more well rounded view.[3] The prevailing portrayal of Native Americans in American literature, especially children's books, primarily view natives as people who just went away, and were always going to. Viewing them through their perspective shows that they are people who have survived. Erdrich also planned to create a series of books depicting the displacement of her people over a century, and how they ended up in Turtle Mountain North Dakota.[6] So far she has completed 5 books: The Birchbark House (1999), The Game of Silence (2005), The Porcupine Year (2008), Chickadee (2012), and Makoons (2016).[7]

Erdrich researched for The Birchbark House through past stories from oral history and texts. She also read through trappers' journals which had accounted for the epidemic and the moving of her people. Some parts of the book were inspired from her own life. Many of the illustrations and storylines were first hand experiences, like her own pet crow or a makak (birchbark eating bowl). Some characters, like Old Tallow, are based on actual people. Her character resembles a real six foot Ojibwa bear hunter, who had a pack of dogs and a statement coat. Omakayas’s name is taken from a tribal roll, which uses a different spelling than the standard Ojibwa way to say little frog, which would be “Omakakeens.” Erdrich guessed either it was a lost dialect or a misspelling, and chose to use this older version of the word to keep it grounded in the time period.[3]

Structure and plot

The novel, which takes place on Lake Superior, is separated into the four seasons. However, before the book begins in Summer it opens with a prologue. The prologue seems out of place but it fulfills an important part of the plot of the book. The four seasons, as follows, are summer, fall, winter, and finally spring. Inside each season Erdrich defines the experiences Omakayas has with fellow community members and the nature around her.

The structuring of the seasons helps show the connectedness to nature this novel holds. Instead of thinking of months and years, the seasons and climate are some of the only true measurements of time necessary to the lifestyle of our main characters. The structure of the book provides insight into Omakayas and her family’s lifestyle but also about Ojibwe culture. “Many traditional Ojibwe stories are passed from elders to younger generations and serve to strengthen intergenerational relationships and teach valuable lessons to children, while others are told just for entertainment purposes. Some of the most common and widely known stories are those about the origins of various animals, traditions, and other aspects of Ojibwe history and culture.”[8]

While the seasons are an important part of the structuring of the novel, the prologue breaks this established structure and starts the book off with a small instance of foreshadowing. Without any context, The Birchbark House begins with the sentence “The only person left alive on the island was a baby girl.” The following portions of the novel, divided into seasons, show Omakayas’ day to day life. Encountering and connecting with animals, spending time with her family, as well as learning skills, and facing challenges along the way.

Not until the end of this novel is Omakayas’ secret unveiled, and the connection from the prologue fully explained. That secret is her ability to “heal” those around her. Louise Erdrich tends to structure books in this manner, saving information, most of the time regarding familial status, alongside the protagonist’s true origins until the end. For example, this structuring is used in Erdrich’s novels Love Medicine and Future Home of the Living God.[9]

Characters

One of the central themes of Erdrich's novel is community. There are many characters in The Birchbark House. The following are the characters most of the novel is centered on.

Omakayas - Omakayas is the 7-year-old protagonist of the novel. Although she has complicated feelings about her siblings, she loves her family very much. Her healing gift became evident when her tribe fell ill from smallpox. She is brave, caring, selfless, and compassionate. Despite her name not being a direct translation of any Ojibwe word, it can be inferred that it is rooted from makwa, meaning bear, and aya, meaning owning.[10]

Nokomis – The maternal grandmother of Omakayas. She lives with Omakayas and her family. She mentors Omakayas to listen to the land and demonstrates her connection to nature through her offerings of tobacco leaves. After tough times befall her family, Nokomis dreams the location of a deer, which once it was hunted and killed, saved the family from starvation. Nokomis is wise, strict, and reliable.

Yellow Kettle (Mama) – Omakayas's mother is a strong woman who does not often display her anger, but at times her anger pours out. She is the one who keeps the family structure intact while Deydey is traveling. The direct translation of yellow kettle into Ojibwe is Ozaawi Akik. Akik is the Ojibwa word for kettle; however it also has a second meaning: engine or motor. Also, with ozaawaabikad meaning brass,[11]

Deydey (Mikwam) – Omakayas's father is mixed race, half-white and half-Ojibwa. He is a trader who is gone trading during some of the novel. He has a strong personality tempered by moments of tenderness and care. The meaning of Mikwam in the Ojibwe language is 'ice.'[12]

Neewo - Omakayas' baby brother whoM Omakayas loves very much. She often pretends that Neewo is her own baby. Neewo feels a stronger connection to Omakayas than he has to his other siblings. He falls victim to the smallpox epidemic. Readers learn that Omakayas has some form of immunization from the disease, and Neewo may find a subconscious feeling of safety being around Omakayas. The name Neewo comes from the Ojibwa word niiwogonagizi, meaning fourth (typically of the month).[13] This is a direct naming as he is the fourth child in the family.

Angeline – Omakayas's older sister whom Omakayas loves but is very jealous of due to perceived perfection. Angeline is very smart and is known in the community for her beauty and her excellent skills in beading. She is usually kind to Omakayas, but can be cold-hearted.

Pinch – Omakayas's younger brother whom Omakayas loves. As his sister, Omakayas sees the flaws in his character, such as his laziness. Pinch is also something of a trickster, often using his wits to get out of undesirable tasks. Omakayas does not enjoy Pinch. Pinch saves everyone at the end.

Fishtail - Fishtail was a close friend of Deydey and Ten Snow’s husband. He also is one of the members in the community who is learning to read the tracks of the whites. In other words, he is attempting to learn the English alphabet to better aid communication and treaty negotiations with the whites.

Ten Snow – Ten snow is a connection to the family. She is a close friend of Angeline and Fishtail’s wife. She, along with many others, was a victim of the smallpox epidemic.

Old Tallow – A neighbor in the tribe who acts as an “aunt” figure to Omakayas. Omakayas understood that Old Tallow treated her with more respect than she did the other children, whom Old Tallow would yell at and send away from her cabin.[3] When the family and community are suffering through the smallpox epidemic, Old Tallow helps Omakayas care for the sick. At the end of the novel, Old Tallow revealed Omakayas’s origins, helping her to emotionally heal from the death of her younger brother.

Andeg – An injured crow who became Omakayas’s pet after Omakayas nursed him back to health. Through Andeg, readers have a sense of the connection Omakayas has with animals. Andeg is the Ojibwa word for crow.[14]

Themes

Culture

The Birchbark House relies heavily on the storytelling tradition of the Ojibwe culture.[15] Storytelling forms a basis for the relationship between Omakayas and her grandmother Nokomis. Within The Birchbark House, stories are something the family, especially Omakayas, look forward to and cherish during the harsh winter months when these stories are told more commonly.

Not only does Erdrich depict oral storytelling throughout the book but she also briefly describes the Ojibwe tradition of pow wows. Despite the harsh winter months the Ojibwe people have found ways to not only embrace their culture but have fun. As stated within the novel, “Standing at the center with Ten Snow, she gracefully danced to the beat. Thimbles ringing, her body moved in exact time… Trade silver tokens, bracelets, armbands, crosses flashed and ribbons swirled as the dancers moved in joy and excitement…”.[1] This is one of many monumental moments throughout the year for the Ojibwe people; as they also come together for both rice gathering and maple sugar collection. Events like these allow the Ojibwe to come together as one and celebrate not only their indigenous roots, but also their means of survival.

Language

Erdrich has conveyed the importance of the Ojibwa language within the storytelling in the novel. According to Sabra McIntosh, "[Stories] pass on family history, folklore, superstitions and customs. Nokomis tells stories in the cold of winter. Deydey tells stories whenever he is home, usually about his travels. The family and especially the children relish story telling time. We know from the author’s notes that Ojibwa was a spoken, not written, language. Their history and identity survives through such storytelling."[16]

Reception

Peter G. Beilder, writing in the journal Studies in American Indian Literature, said, "Much of the story, perhaps too much of it, is taken up with what we might think of as cultural background about Ojibwa life."[17] He also notes: "many readers will recognize the now-familiar Erdrich style that borders on overwriting but stops just short."[17] Beidler argues that the book sometimes gets a little redundant and over-explained; however he still enjoyed the novel. He praises the characters, noting how Omakayas learns from her elders. Little features like this give good characterization.[17]

References

- 1 2 "The Birchbark House". National Book Foundation. Archived from the original on April 15, 2022. Retrieved May 10, 2022.

- ↑ Erdrich, Louise. The Birchbark House, 1999.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "TeachingBooks | Author & Book Resources to Support Reading Education". www.teachingbooks.net. Retrieved 2022-09-14.

- ↑ "Louise Erdrich On Her Personal Connection To Native Peoples' 'Fight For Survival'". NPR.org. Retrieved 2022-09-14.

- ↑ Stirrup, David (2013-07-19), "Native American literature", Louise Erdrich, Manchester University Press, doi:10.7765/9781847793485.00006, ISBN 978-1-84779-348-5, retrieved 2023-11-01

- ↑ admin (2007-08-17). "The Girl from Spirit Island". About ALA. Retrieved 2022-09-14.

- ↑ "Birchbark House Series by Louise Erdrich". www.goodreads.com. Retrieved 2022-09-14.

- ↑ "Lake Superior Ojibwe Gallery Learning Guide". 1854 Treaty Authority. 3 December 2018. Retrieved 2022-09-14.

- ↑ Beidler, Peter G. (2000). "Review of The Birchbark House". Studies in American Indian Literatures. 12 (1): 85–89. ISSN 0730-3238. JSTOR 20736953.

- ↑ "The Ojibwe People's Dictionary". ojibwe.lib.umn.edu. Retrieved 2022-09-14.

- ↑ "The Ojibwe People's Dictionary". ojibwe.lib.umn.edu. Retrieved 2022-09-14.

- ↑ "The Ojibwe People's Dictionary". ojibwe.lib.umn.edu. Retrieved 2022-09-14.

- ↑ "The Ojibwe People's Dictionary". ojibwe.lib.umn.edu. Retrieved 2022-09-14.

- ↑ "The Ojibwe People's Dictionary". ojibwe.lib.umn.edu. Retrieved 2022-09-14.

- ↑ Gargano, Elizabeth (2006). "Oral Narrative and Ojibwa Story Cycles in Louise Erdrich's The Birchbark House and The Game of Silence". Children's Literature Association Quarterly. 31 (1): 27–39. doi:10.1353/chq.2006.0027. ISSN 1553-1201. S2CID 144812437.

- ↑ McIntosh, Sabra. "The Birchbark House". Archived from the original on 23 August 2006.

- 1 2 3 Beidler, Peter G. (Spring 2000). "Review of The Birchbark House". Studies in American Indian Literatures. 12 (1 (Children's Literature)): 85–89. JSTOR 20736953 – via JSTOR.