| The Burning | |

|---|---|

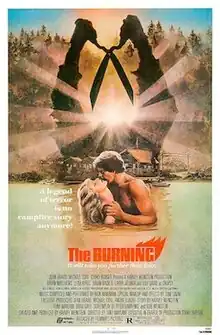

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Tony Maylam |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Story by |

|

| Produced by | Harvey Weinstein |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Harvey Harrison |

| Edited by | Jack Sholder |

| Music by | Rick Wakeman |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Filmways Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 91 minutes[2] |

| Country | United States[1] |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $1.5 million |

| Box office | $707,770 (United States/Canada) |

The Burning is a 1981 American slasher film directed by Tony Maylam, and starring Brian Matthews, Leah Ayres, Brian Backer, Larry Joshua, and Lou David. Its plot follows a summer camp caretaker who is horribly burnt from a prank gone wrong, where he seeks vengeance at a nearby summer camp years later. The film marks the debuts of actors Jason Alexander, Fisher Stevens, and Holly Hunter.

Based on the New York urban legend of the Cropsey maniac, the screenplay was written by Bob Weinstein and Peter Lawrence, from a story conceived by producer Harvey Weinstein, Tony Maylam, and Brad Grey. Rick Wakeman, of the progressive rock band Yes, composed the score.

The Burning was theatrically released on May 8, 1981, by Filmways. Its critical reception was largely unfavorable, with many film critics deriding its similarities to Friday the 13th and Friday the 13th Part 2 and its graphic violence. However, it has since become a cult classic[3] and received positive reappraisal from film critics.

Plot

One night at Camp Blackfoot, several campers pull a prank on Cropsy, the camp's alcoholic and abusive caretaker, by setting a worm-riddled skull with candles in the eye sockets next to his bed. When the caretaker is awoken by the campers banging on his window, he gets frightened by the skull and accidentally knocks it onto his bed, starting a fire. The flames reach a gas tank, which ignites Cropsy and his cabin. He runs outside, engulfed in flames, and stumbles down into a river as the boys flee. Despite his horrific injuries, Cropsy survives.

Five years later, Cropsy is released from the hospital despite dealing with failed skin grafts and wears a coat and hat to hide his disfigurement. A prostitute lures him to her apartment, where he stabs her with scissors in a fit of rage. He then arms himself with a pair of pruning shears and sets out for another summer camp, Stonewater. There, the counselors and campers are playing softball when a camper searching for a lost ball in the woods narrowly avoids Cropsy.

The next morning, a camper named Alfred scares Sally as she steps out of the shower. Her screams bring the attention of counselors Michelle and Todd, and campers Karen and Eddy catch him. Michelle is furious at Alfred and demands that he leaves, but Todd talks to him. He learns that Alfred has no friends and was merely pulling a prank on Sally. Sally's boyfriend Glazer confronts Alfred, but Todd gets him to back off, and the latter apologizes to Sally. Alfred spots Cropsy outside his window that night, but nobody believes him.

The following day, the campers are brought by Todd and Michelle on a canoe trip down to the river Devil's Creek. After Todd tells them about the legend of Cropsy, Karen and Eddy go to a lake to skinny dip. He leaves upset when she reconsiders having sex with him, and Karen leaves the lake to find her clothes scattered in the woods. As she collects them, Cropsy slashes her throat with his shears. The next morning, Michelle finds Karen and the canoes missing. Eddy, Fish, Woodstock, Diane, and Barbara search for the canoes on a makeshift raft. They spot a canoe and paddle to it, but Cropsy ambushes them by jumping out from the canoe and savagely murders them all with his shears.

Glazer has sex with Sally in the woods but suffers premature ejaculation. When he leaves to get matches for a campfire, Cropsy shoves his shears into Sally's chest. Her boyfriend returns only for Cropsy to stab him through the throat and pin him to a tree. Alfred witnesses his death and wakes up Todd, but Todd is rendered unconscious by Cropsy, who then chases after Alfred. Meanwhile, Michelle finds the mutilated bodies on the makeshift raft and brings the remaining campers back to the camp to contact the authorities.

Todd regains consciousness and chases after the killer with an axe. Cropsy grabs Alfred inside an abandoned mineshaft and pins him to a wall with his shears. Todd discovers Karen's body and sees Cropsy armed with a flamethrower, where he begins to remember being involved with the prank. He is attacked by Cropsy, who reveals his disfigurements, and Alfred frees himself to stab him with his own shears. Before they can leave, Cropsy reappears, and Todd ultimately slams the axe into his face, killing him. Alfred ignites his body with his own flamethrower, and they make their way outside to Michelle, who brought the police with her, as Cropsy's body burns away. At a campfire, another group of teenagers is seen retelling the story of Cropsy.

Cast

- Brian Matthews as Todd

- Keith Mandell as Young Todd

- Leah Ayres as Michelle

- Brian Backer as Alfred

- Lou David as Cropsy

- Larry Joshua as Glazer

- Jason Alexander as Dave

- Ned Eisenberg as Eddy

- Carrick Glenn as Sally

- Carolyn Houlihan as Karen

- Fisher Stevens as Woodstock

- Shelley Bruce as Tiger

- Sarah Chodoff as Barbara

- Bonnie Deroski as Marnie

- Holly Hunter as Sophie

- Kevi Kendall as Diane

- J.R. McKechnie as Fish

- George Parry as Alan

- Ame Segull as Rhoda

- Jeff De Hart as Supervisor

- Bruce Kluger as Rod

- Jerry McGee as Intern

- Mansoor Najeeullah as Orderly

- Willie Reale as Paul

- John Roach as Snoop

- K.C. Townsend as Hooker

- John Tripp as Camp Counselor

- James Van Verth as Jamie

- Therese Morreale as Girl Playing Softball

Production

Conception

In 1980, Harvey Weinstein was desperate to break into the movie business. Weinstein and producing partner Michael Cohl recognized the success of low-budget horror films such as The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974) and Halloween (1978), and began swapping horror stories. Having heard stories about the Cropsy legend when he was a young camper in upstate New York, Weinstein brought the idea to Cohl, who loved it.[4]

The project was initiated before the popularity of Sean S. Cunningham's sleeper hit Friday the 13th (1980), with Harvey Weinstein creating a five-page treatment in 1979 under the title "The Cropsy Maniac" and registering it in April 1980, a full month before Cunningham's film was released. Coincidentally, at the same time, director Joseph Ellison also had a film in pre-production under the title "The Burning", but changed the name to Don't Go in the House (1980) to avoid confusion with Weinstein's film. The production also bore similarities to another slasher movie in pre-production, a film that would become known as Madman (1982). In summer 1980, during a casting call for Madman, one of the actresses commented that her boyfriend was acting in The Burning. This prompted Madman to change its entire premise, which was built around the Cropsy legend. This led to a delay in its filming until October 1980, which proved costly as it didn't receive a theatrical release until January 1982. The over-saturation of genre films competing with each other was one of the side-effects of the early 1980s slasher boom.[4]

Cohl told Variety that he, Weinstein and producer Corky Burger took an early version of the script to the 1980 Cannes Film Festival, where it was well received, although they rejected initial six-figure offers, hoping to land more money once the film had been shot. This was a similar approach to how Friday the 13th had earned distribution with Paramount Pictures.[4]

British director Tony Maylam, known for rock music documentaries in the 1970s, was hired as The Burning's director in summer 1980. Maylam had met Weinstein and Burger while the producers worked as rock promoters.[4]

During his discussion with film critic Alan Jones on the audio commentary of MGM's DVD, Maylam said that once he came on board things moved very quickly. The screenplay was written in just six weeks and was sculpted to conform to the emerging genre conventions of the time. As the film takes place mostly outside and is set in summer, the production had a small window of opportunity in which to make the film or it risked having to wait until the following year. Knowing that the slasher craze would not last forever, and wanting to get their film released before it fizzled out, the producers rushed into production. The screenplay was written by Peter Lawrence and Harvey's brother Bob Weinstein. Again, reflecting an understanding of slasher movie conventions of the time, the script featured a murder every ten minutes in the script. It was Maylam's idea to make gardening shears Cropsy's weapon of choice.

The film originally had a different ending. A script dated July 6, 1980 shifted the location to one much more in keeping with a summer camp slasher. Originally, the showdown was to take place in a boathouse. Another big change is that Todd ends up as the "final boy" rather than as the heroic adult, and Alfred is killed by Cropsy. Other changes included an excised character named Alan, who was to be the love interest for Tiger. This version also ends with a campfire scene, but the last line is different: "...And every year he seeks revenge for the terrible things those kids did to him ... every year he kills!"[4]

The production company became Miramax, named after Harvey and Bob Weinstein's parents, Miriam and Max, who helped fund the picture. The budget is reported to have been between $500,000 and $1.5 million, although the latter is more often cited. Cohl admitted that the relatively inexperienced filmmakers underestimated production costs, which caused the movie to go over budget.[4]

Casting

Casting took place in New York in the spring of 1980, and Maylam met most of the cast in person. There was a remarkably quick turnaround, as the start date for filming was August 18, 1980 (although some shooting may have taken place prior to this date). Brian Matthews and Leah Ayres were cast first. Ayres already had a successful small screen career. Maylam reportedly insisted that Matthews dye his hair brown, as he did not think he would look macho enough with blonde hair. Larry Joshua was cast as one of the kids at the camp, even though he was older in real life than either Matthews or Ayres. Like most of the cast, it was his first role, but led to a long and successful career, mostly on the small screen. The rest of the cast was hired during a series of auditions. For some of the soon-to-be-stars, such as Holly Hunter, Jason Alexander, and Fisher Stevens, The Burning was the first big screen appearance.[4]

The Weinsteins and Maylam also secured the services of make-up supremo Tom Savini, who they flew to Pittsburgh to meet. Savini had worked on films such as Dawn of the Dead (1978), Friday the 13th (1980), Maniac (1980), and Eyes of a Stranger (1981). Savini turned down the chance to work on Friday the 13th Part 2 (1981), ostensibly because he could not understand the logic that Jason was fully grown and was now the killer, as well as what he described as "miscommunications" with the film's backers. He also said that he liked the script for The Burning more.[4]

Filming

The Burning was shot in the late summer of 1980 around Buffalo and North Tonawanda, New York. Much of the filming took place in and around existing summer camps to give it an authentic look while keeping costs down. The cast wore their own clothes throughout the production. Many of the cast were local to the New York area and were aware of the Cropsy legend.[5]

In the interview on the MGM DVD, Savini recalls that the cast were literally queuing up to find out how they would die, making him feel like an assassin. He was very hands-on with the production, though he did not have much time to put together the special effects. He only had three or four days to make the Cropsy make-up – the mask was created in his dressing room in-between special effects duties elsewhere on the film. In Grande Illusions, his first book on his life as a special effects guru, Savini says he based the look of Cropsy on a burnt beggar he had seen as a kid in Pittsburgh, as well as textbooks on burn victims. Due to time constraints, the resulting mask was more of a melt than a burn. Savini was pleased enough with what he had done that he subsequently agreed to go on a publicity tour for the film.[5]

Savini expanded on his Friday the 13th experience for his work on The Burning. The scene where a victim has her throat cut by Cropsy with the shears was similar in execution to the demise of the hitchhiker in the earlier film. Cropsy's demise, when the axe smashes into his face, is an almost identical effect to a scene in Friday the 13th.[5]

There has been much speculation as to why the mine system was chosen for the climactic battle between Cropsy and Todd. As an earlier script showed, it was originally meant to be a boat house at the camp, but this was switched to a cave system. Indeed, another subsequent version of the script has a scene in Cropsy's lair, where he looks over old newspaper clippings. Maylam says it was changed again to the copper mine because they found bats roosting in the boat house and considered it unsafe.[5]

Maylam has recalled that Carolyn Houlihan, who was Miss Ohio USA in 1979, found her nude scenes extremely difficult to do. Carrick Glenn, who also had a nude scene, was relaxed in front of the camera, according to the director.[5]

Maylam maintains that he was Cropsy for about 90% of the movie, as he could not get anyone else to hold the shears the way he wanted (to perfect the gleam bouncing off the metal).[5]

Post-production

The film was edited by Jack Sholder, who went on shortly to direct the first film for New Line Cinema, the slasher Alone in the Dark (1982), starring Jack Palance, Martin Landau, and Donald Pleasence. He also directed A Nightmare on Elm Street 2: Freddy's Revenge (1985), a sequel to the 1984 classic.[5]

Maylam has said that there was talk of a sequel at the time The Burning was wrapping; however, Maylam was leery of being type-cast as a horror director and the disappointing box office performance of the original stalled the sequel's production.[5]

Promotion and release

According to Maylam, the film received a very good response at test screenings. In February 1981, Filmways Pictures picked up the rights to distribute the film from Miramax for an undisclosed sum after viewing it in Los Angeles. According to Variety, Filmways was in financial difficulties and saw an opportunity to make quick money during the slasher boom. The company had already produced Brian De Palma's Dressed to Kill (1980), which had made serious money the previous year. Filmways also released horror thrillers such as The Town That Dreaded Sundown (1976), Without Warning (1980), and The Last House on the Left (1972). Filmways originally was intent on renaming the film Tales Around the Campfire due to its now-iconic campfire scenes, but its original title remained. The film was subsequently sold to foreign territories including Britain, Germany, France, Spain and Japan at the 1981 Cannes Film Festival.[6]

Box office

The film opened on May 8, 1981, in Florida on 110 screens, with a regional rollout following on May 22.[7][8]

According to Variety, the film did especially well in Buffalo, near where it had lensed, playing in three theaters and two drive-ins, bringing in $33,000. Interest soon fizzled, and the film suffered a more than 50% drop-off in box office receipts the following week.[6] Despite this brief bright spot, overall box office for The Burning was initially pretty dismal. It lasted in the top 50 for only four weeks, with a take of just $270,508. Variety reported it received a "chilly reception" in San Francisco and Chicago. Unlike in Buffalo, it opened elsewhere to stiff competition: it debuted at number 23 behind slasher films Happy Birthday to Me, which was at number one, and Friday the 13th Part 2 at number two; however, The Burning also opened on far fewer screens than those wider releases.[6]

The oversaturation of the slasher film market did not help draw in audiences to The Burning. Aside from having the very similar-plotted Friday the 13th Part 2 also playing, the film suffered from competition with Happy Birthday to Me, Final Exam, The Fan, Graduation Day, Eyes of a Stranger, and a successful re-release of Tobe Hooper's The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. The success of Friday the 13th Part 2 hampered The Burning's attendance, as the audience flocked to the known property.[6]

The Burning opened in New York with new poster artwork (showing a face with a fire reflected in an eye) on November 5, 1982, distributed by Orion Pictures, who had recently merged with Filmways.[7] The New York Times film critic Janet Maslin's gave a scathing review.[9] An ad in Variety from November 17 noted that the film had grossed $401,258 in just 7 days.[7] Its last week on Variety sample chart was December 8, where it had slipped from 78 screens the previous week to just 8 that week, with a final gross of $707,770.

Promotional press artwork also exists under the title Cropsy, but it is unclear when it played theaters under that title, as it was a common practice to give films multiple names in an effort to trick audiences into seeing it multiple times. According to the MPAA site, it may have also played under the title Campfire Tales. These releases and re-releases make it difficult to find a definitive box office tally for the film.[6]

According to Tony Maylam, the film sold well around the world, making back its $1.5 million budget. The film performed well in Japan when it was released there in September 1981.[10][11] Variety reported it making a total of $283,477 in a week at just four cinemas in Tokyo.[10] In its first 16 days, it had grossed $1.2 million from 11 theatres in Japan.[10]

The film was released to British screens on November 5, 1981, by HandMade Films, where it was met with modest success. Within a couple of weeks it was on a double feature with When a Stranger Calls (1979), which did not boost its fortunes, as Variety said it soon "hit the skids" with "pathetic" results.[6]

Censorship

Despite the graphic gore effects of slasher films being the driving force behind their box office success, the MPAA gave in to the critical reception and reaction of pressure groups who were protesting the films in the wake of violent acts, such as the assassination of John Lennon, and the growing debate about violence in the media. The Burning was heavily trimmed to receive its R rating. The film remained cut in the United States until its 2007 DVD release that restored the scenes of gore.[6]

The British cinema release of The Burning was severely cut as well by the BBFC, receiving an X certificate on September 23, 1981, with cuts to the scissor murder of the prostitute and some gore during the raft attack. When the film was accidentally released uncut on video in the United Kingdom by Thorn EMI, the tape was liable for seizure and prosecution under the Obscene Publications Acts. Thorn-EMI had unwittingly released a "video nasty", a term used to coin films judged as obscene and too violent for home rental. They tried to rectify matters by reissuing a BBFC-approved version. The original uncut Thorn-EMI release is worth a great deal of money today. In 1992, the United Kingdom video re-release suffered additional cuts to the raft attack, plus cuts to the killing of Karen. It was finally released fully uncut in 2002.[6]

Critical response

On Rotten Tomatoes, the film has an approval rating of 77% based on reviews from 13 critics, with an average rating of 6.90/10.[12] On Metacritic, the film has a weighted average score of 42 out of 100, based on reviews from 5 critics, indicating "mixed or average reviews".[13]

A number of critics noted the film's graphic violence and parallels to Friday the 13th (1980) and its sequel: On his weekly "Sneak Previews" show with Gene Siskel, Roger Ebert chose the film as one of the critics' "Dogs of the Week"; Ebert was particularly unimpressed by the film's similarity to Friday the 13th Part II, another slasher film from the summer of 1981 that he despised. Bill Cosford of the Miami Herald praised the film's dialogue and special effects as convincing, but similarly noted that it bore too many similarities to films such as Friday the 13th and Friday the 13th Part II.[14] Joe Baltake of the Philadelphia Daily News also compared the film to Friday the 13th, but added that, where that film "is periodically nasty, The Burning is all nastiness."[15] A review published in Variety was similarly critical of the film, describing it as derivative and overtly violent.[16]

Janet Maslin of The New York Times wrote: "The Burning makes a few minor departures from the usual cliches of its genre, though it carefully preserves the violence and sadism that are schlock horror's sine qua non".[9]

The Time Out film guide wrote: "Suspensewise, it's proficient enough, but familiarity with this sort of stuff can breed contempt".[17] Kim Newman of Empire magazine was critical of the film for being "an obvious imitation of Friday the 13th" but praised Tom Savini's special effects.[18] AllMovie wrote: "With deliberant pacing and shocking scenes of full-on gore, The Burning delivers on the creep-out levels and would probably be better regarded if not for the boom of familiar flicks that came out after this release".[19] While reviewing the film's 2013 Blu-ray release from Scream Factory, Scott Weinberg of Fearnet wrote, "[The Burning is] dated and sort of dull. But there's some amazing gore, and the new Blu-ray makes it shine".[20] Leonard Maltin gave the film one out of a possible four stars, calling it "[an] awful Friday the 13th rip-off".[21]

Home media

The Burning was released on DVD in North America for the first time ever on September 11, 2007, by MGM Home Entertainment.[22] The DVD contains several extras, including a commentary by director Tony Maylam, a featurette covering Savini's make-up effects, a stills gallery, and the theatrical trailer. Despite the DVD cover displaying the 'R' rating, the print used is the full uncut version.[23]

Shout! Factory released The Burning on Blu-ray Disc/DVD Combo Pack on May 21, 2013, under their sub-label Scream Factory.[24] In May 2023, Scream Factory announced a forthcoming Ultra HD Blu-ray release scheduled for July 11, 2023.[25]

Soundtrack

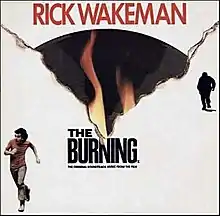

| The Burning | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Soundtrack album by | ||||

| Released | 1981 | |||

| Recorded | 1981 | |||

| Studio | Workshoppe Recording Studios, New York | |||

| Genre | Progressive rock | |||

| Length | 35.42 | |||

| Label | Charisma | |||

| Producer | Rick Wakeman | |||

| Rick Wakeman chronology | ||||

| ||||

A soundtrack album featuring Rick Wakeman's score was released on LP in 1981 in Europe, and shortly after in the United States and Japan.[26] It includes music from the film and rock band arrangements by Wakeman, known as The Wakeman Variations, as well as selections from the score, written by Alan Brewer and Anna Pepper. Brewer was musical director for the film and co-producer of the score and soundtrack album with Wakeman.[27][28]

The soundtrack was released in the United Kingdom for the first time on CD in February 2007.[29]

- Track listing[27]

- "Theme from The Burning" – 3:32

- "The Chase Continues (Po's Plane)" – 3:53

- "Variations on the Fire" – 5:13

- "Shear Terror and More" – 4:39

- "The Burning (End Title Theme)" – 2:00

- "Campfire Story" – 3:08

- "The Fire" – 3:25

- "Doin' It" – 2:42

- "Devil's Creek Breakdown" – 2:21

- "The Chase" – 2:00

- "Shear Terror" – 2:49

Legacy

Many people involved in The Burning have gone onto achieve great success. Bob and Harvey Weinstein have become successful film producers, acting as founders and heads of Miramax Films from 1979 until 2005 (which was owned by The Walt Disney Company from 1993 until 2010), when they created The Weinstein Company. Bob is also the founder and head of Dimension Films, which continues to release genre films, though many of them heavily reedited by Weinstein from 1992 until 2019, including the successful Scream slasher film franchise and five of the Halloween films. Harvey won an Academy Award for producing Shakespeare in Love and has garnered seven Tony Awards for producing a variety of winning plays and musicals, including The Producers, Billy Elliot the Musical, and August: Osage County. Brad Grey, who received a writing credit on The Burning, became the chairman and CEO of Paramount Pictures, a position he held from 2005 until his death in 2017. Grey produced eight of the ten top-grossing films to come from the studio. Actress Holly Hunter won an Academy Award in 1993 for her performance in The Piano, and was also nominated for her performances in Broadcast News (1987), The Firm (1993), and Thirteen (2003), as well as winning two Emmy Awards and receiving seven nominations. Jason Alexander would star in the long-running, critically acclaimed sitcom Seinfeld as George Costanza. Fisher Stevens would star in The Flamingo Kid (1984) and Short Circuit (1986), before turning to documentary directing, where he won an Academy Award for his film The Cove (2010) and an Independent Spirit Award for Crazy Love (2007).

The film was cited by Hifumi Kono as being the inspiration for Bobby Barrow's signature scissors weapon in Clock Tower.[30]

In 2009, writer-director Joshua Zeman and director Barbara Brancaccio released a documentary titled Cropsey, which details the Cropsey maniac urban legend on which The Burning is based. Despite sharing little connection to The Burning, the film re-ignited the popular mythos of the character.[31]

In 2017, Complex magazine named The Burning the 12th-best slasher film of all time.[32] The following year, Paste included it in their list of "The 50 Best Slasher Movies of All Time",[33] while Cropsy was ranked the 12th-greatest slasher villain of all time by LA Weekly.[34]

In October 2017, former-production assistant Paula Wachowiak alleged that producer Harvey Weinstein's history of predatory behavior went back as far as the initial filming of The Burning in June 1980. Then a 24-year-old University at Buffalo graduate and divorced mother, Wachowiak was tasked with getting Weinstein to sign checks for an auditor working with the production's accounting department. When Wachowiak arrived at Weinstein's hotel room to have him sign the checks, he allegedly answered the door wearing only a towel, that he then dropped and asked for a massage from his employee. When Wachowiak refused, she alleges that Weinstein harassed her about the incident through the rest of the film's production, up until the film's May 1981 premiere.[35]

References

- 1 2 "Credits". BFI Film & Television Database. London: British Film Institute. Archived from the original on May 6, 2014. Retrieved May 6, 2014.

- ↑ "THE BURNING (X)". HandMade Films. British Board of Film Classification. September 23, 1981. Retrieved July 25, 2013.

- ↑ Jamie Lee. "Do You Feel The Burning? A Review". Yell Magazine. Retrieved December 6, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Kerswell, J.A. "The Burning (1981) pre-prod". Hysteria-Lives. Retrieved August 19, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Kerswell, J.A. "The Burning (1981) Production". Hysteria-Lives. Retrieved August 19, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Kerswell, J.A. "The Burning (1981) Promotion". Hysteria-Lives. Retrieved August 19, 2014.

- 1 2 3 The Burning at the American Film Institute Catalog. Retrieved May 27, 2023.

- ↑ "Filmways schedules a new horror movie". The Times. April 1, 1981. p. 23 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 Maslin, Janet (November 5, 1982). "'Burning,' from Horror Genre". The New York Times.

- 1 2 3 "The Burning Scorches Japan". Variety. October 7, 1981. p. 29.

- ↑ Jerome, Deborah (November 5, 1982). "The "Burning" is rather routine". The Record. p. 32 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "The Burning (1981)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved August 19, 2023.

- ↑ "The Burning". Metacritic.

- ↑ Cosford, Bill (May 11, 1981). "'Burning' filmgoers will feel some familiar chills". Miami Herald. p. 5C – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Baltake, Joe (May 27, 1981). "Audience May Burn You Up At Gore Flick of the Week". Philadelphia Daily News. p. 26 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Variety staff (May 24, 1981). "'The Burning' fizzles under barrage of gore". Courier-Post. p. 6F – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Milne, Tom, ed. (1991). The Time Out Film Guide (Second ed.). Penguin Books. p. 92.

- ↑ Kim Newman (January 1, 2000). "The Burning". Empire.

- ↑ Wheeler, Jeremy. "The Burning – Review – AllMovie". AllMovie. Retrieved July 21, 2012.

- ↑ Weinberg, Scott (May 22, 2013). "The Burning (1981) Blu-ray Review". Fearnet. Archived from the original on June 14, 2013.

- ↑ Maltin, Leonard (2013). Leonard Maltin's 2014 Movie Guide. Penguin Press. p. 199. ISBN 978-0-451-41810-4.

- ↑ "The Burning". Amazon.com. Retrieved July 6, 2012.

- ↑ "'Rewind' DVD comparison". Dvdcompare.net. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- ↑ "The Burning and The Town That Dreaded Sundown: Blu-ray/DVD Cover Art and Release Details". Daily Dead. February 2013. Retrieved October 1, 2014.

- ↑ Squires, Jon (May 1, 2023). "1980s Slasher 'The Burning' Gets a 4K Ultra HD Upgrade This Summer". Bloody Disgusting. Archived from the original on May 28, 2023.

- ↑ "Burning, The (1981)". Soundtrackcollector.com. Retrieved July 6, 2012.

- 1 2 Stephen Raiteri. "The Burning – Rick Wakeman : Songs, Reviews, Credits, Awards". AllMusic. Retrieved July 6, 2012.

- ↑ "BME: Rick Wakeman, Nashville Film Festival". bmemusic.com. Retrieved July 6, 2012.

- ↑ "The Burning". Amazon.com. Retrieved July 6, 2012.

- ↑ "THIS IS COMPLETELY TRUE. (About Nude Maker and CT)". w11.zetaboards.com. July 19, 2007. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- ↑ Kerswell, J.A. "Cropsy Legend". Retrieved August 19, 2014.

- ↑ Barone, Matt (October 23, 2017). "The Best Slasher Films of All Time". Complex. Archived from the original on July 23, 2020.

- ↑ Vorel, Jim (August 8, 2018). "The Best Slasher Movies of All Time". Paste. Archived from the original on July 23, 2020.

- ↑ Byrnes, Chad (October 22, 2018). "A Killer List: The Greatest Movie Slashers of All Time". LA Weekly. Archived from the original on July 23, 2020.

- ↑ Becker, Maki (October 15, 2017). "'You disgust me': Buffalo woman tells of 1980 encounter with Weinstein". The Buffalo News. Archived from the original on May 28, 2023.