| The Cat and the Canary | |

|---|---|

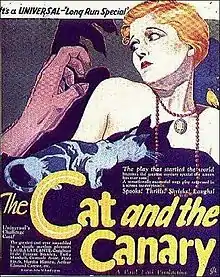

.jpg.webp) Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Paul Leni |

| Screenplay by | |

| Story by |

|

| Based on | The Cat and the Canary by John Willard |

| Produced by | Paul Kohner |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Gilbert Warrenton |

| Edited by | Martin G. Cohn |

| Music by | Hugo Riesenfeld |

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 82 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | Silent film / English intertitles |

The Cat and the Canary is a 1927 American silent comedy horror film directed by the German Expressionist filmmaker Paul Leni. An adaptation of John Willard's 1922 black-comedy play of the same name, the film stars Laura La Plante as Annabelle West, Forrest Stanley as Charlie Wilder, and Creighton Hale as Paul Jones. The plot revolves around the death of Cyrus West, who is Annabelle, Charlie, and Paul's uncle, and the reading of his will twenty years later. Annabelle inherits her uncle's fortune, but when she and her family spend the night in his haunted mansion, they are stalked by a mysterious figure. Meanwhile, a lunatic mainly known as the Cat escapes from an asylum and hides in the mansion.

The film is part of the genre of comedy horror films inspired by 1920s Broadway stage plays. Leni's adaptation of Willard's play blended expressionism with humor, a style for which Leni was notable and recognized by critics as unique. His directing style made The Cat and the Canary influential in the "old dark house" genre of films popular from the 1930s through the 1950s. The film was one of Universal's early horror productions and is considered "the cornerstone of Universal's school of horror".[1] The play has been filmed five other times, most notably in 1939, starring Bob Hope and Paulette Goddard.

Plot

In a decaying mansion overlooking the Hudson River, millionaire Cyrus West approaches death. His greedy family descends upon him like "cats around a canary", causing him to become insane. West orders that his last will and testament remain locked in a safe and go unread until the 20th anniversary of his death. As the appointed time arrives, West's lawyer, Roger Crosby (Tully Marshall), discovers that a second will mysteriously appeared in the safe. The second will may only be opened if the terms of the first will are not fulfilled. The caretaker of the West mansion, Mammy Pleasant (Martha Mattox), blames the manifestation of the second will on the ghost of Cyrus West, a notion that the astonished Crosby quickly rejects.

As midnight approaches, West's relatives arrive at the mansion: nephews Harry Blythe (Arthur Edmund Carewe), Charles "Charlie" Wilder (Forrest Stanley), Paul Jones (Creighton Hale), his sister Susan Sillsby (Flora Finch) and her niece Cecily Young (Gertrude Astor), and niece Annabelle West (Laura La Plante). Cyrus West's fortune is bequeathed to the most distant relative bearing the name "West": Annabelle. The will, however, stipulates that to inherit the fortune, she must be judged sane by a doctor, Ira Lazar (Lucien Littlefield). If she is deemed insane, the fortune is passed to the person named in the second will. The fortune includes the West diamonds which her uncle hid years ago. Annabelle realizes that she is now like her uncle, "in a cage surrounded by cats."

While the family prepares for dinner, a guard (George Siegmann) barges in and announces that an escaped lunatic called the Cat is either in the house or on the grounds. The guard tells Cecily, "He's a maniac who thinks he's a cat, and tears his victims like they were canaries!" Meanwhile, Crosby suspects someone in the family might try to harm Annabelle and decides to inform her of her successor. Before he speaks the person's name, a hairy hand with long nails emerges from a secret passage in a bookshelf and pulls him in, terrifying Annabelle. When she explains what happened to Crosby, the family immediately concludes that she is insane.

Alone in her assigned room, Annabelle examines a note slipped to her which reveals the location of the family jewels, fashioned into an elaborate necklace. She follows the note's instructions and soon discovers the hiding place, in a secret panel above the fireplace. She retires for the night, wearing the diamond-encrusted necklace.

While Annabelle sleeps, the same mysterious hand emerges from the wall behind her bed and snatches the diamonds from her neck. Once again, her sanity is questioned, but as Harry and Annabelle search the room, they discover a hidden passage in the wall and in it the corpse of Roger Crosby. Mammy Pleasant leaves to call the police, while Harry searches for the guard; Susan runs away in hysterics and hitches a ride with a milkman (Joe Murphy). Paul and Annabelle return to her room to search for the missing envelope, and discover that Crosby's body is missing. Paul vanishes as the secret passage closes behind him. Wandering in the hidden passages, Paul is attacked by the Cat and left for dead. He regains consciousness in time to rescue Annabelle. The police arrive and arrest the Cat, who is actually Charlie Wilder in disguise; the guard is his accomplice. Wilder is the person named in the second will; he had hoped to drive Annabelle insane so that he could receive the inheritance.

Cast

- Laura La Plante as Annabelle West

- Creighton Hale as Paul Jones

- Forrest Stanley as Charles Wilder

- Tully Marshall as Roger Crosby

- Gertrude Astor as Cecily

- Flora Finch as Susan

- Arthur Edmund Carewe as Harry Blythe

- Martha Mattox as Mammy Pleasant, housekeeper

- George Siegmann as the Guard

- Lucien Littlefield as Dr. Ira Lazar

- Hal Craig as Policeman (uncredited)

- Billy Engle as Taxi Driver (uncredited)

- Joe Murphy as Milkman (uncredited)

Production

The Cat and the Canary is the product of early 20th-century German Expressionism. According to art historian Joan Weinstein, expressionism includes the art styles of Die Brücke and Der Blaue Reiter, cubism, futurism, and abstraction. The key element that connects these styles is the concern for the expression of inner feelings over verisimilitude to nature.[2] Film historian Richard Peterson notes that "German cinema became famous for stories of psychological horror and for uncanny moods generated through lighting, set design and camera angles." Such filmmaking techniques drew on expressionist themes. Influential examples of German expressionist film include Robert Wiene's The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) about a deranged doctor and Paul Leni's Waxworks (1925) about a wax figure display at a fair.[3]

Waxworks impressed Carl Laemmle, the German-born president of Universal Pictures. Laemmle was struck by Leni's departure from expressionism by the inclusion of humor and playfulness during grotesque scenes.[3] Meanwhile, in the United States, D. W. Griffith's One Exciting Night (1922) began a Gothic horror film trend that Laemmle wanted to capitalize on; subsequent films in the genre like Alfred E. Green's now lost The Ghost Breaker (1922), Frank Tuttle's Puritan Passions (1923), Roland West's The Monster (1925) and The Bat (1926), and Alfred Santell's The Gorilla (1927)—all comedy horror film adaptations of Broadway stage plays—proved successful.[4][5]

Laemmle turned to John Willard's popular play The Cat and the Canary, which centered on an heiress whose family tries to drive her insane to steal her inheritance. Willard hesitated in permitting Laemmle to film his play because, as historian Douglas Brode explains, "that would have exposed to virtually everyone the trick ending, ... destroying the play's potential as an ongoing moneymaker." Nevertheless, Willard was convinced and the play was adapted into a screenplay by Alfred A. Cohn and Robert F. Hill.[6]

Casting

The Cat and the Canary features veteran silent film stars Laura La Plante, Creighton Hale, and Forrest Stanley. According to film historian Gary Don Rhodes, La Plante's part in The Cat and the Canary was typical for women in horror and mystery films: "The female in the horror film ... becomes the hunted, the quarry. She has little to do, and so the question becomes 'What will be done with her?'" Rhodes adds, "The heroines are young and beautiful, but represent more a prize to be possessed—whether "stolen" by a villain or "owned" by a young hero at the films' conclusions."[7] Following The Cat and the Canary, La Plante maintained a career with Universal, but she is described as a "victim of talkies."[8] She received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame before her death in 1996 from Alzheimer's disease.[9]

Universal chose Irish actor Creighton Hale to play hero Paul Jones, Annabelle's cousin. Hale had appeared in 64 silent films before The Cat and the Canary, notably the 1914 serial The Exploits of Elaine and D. W. Griffith's Way Down East (1920) and Orphans of the Storm (1921).[10] Hale's role in The Cat and the Canary was to provide comic relief. According to critic John Howard Reid, "He is forever backing into furniture or finding himself in a risqué position under a bed or wrestling with stray objects like falling books or enormous bed-springs."[11] Hale had trouble finding a solid career in sound film. Many of his parts were minor and uncredited.[12]

The villain Charles Wilder was played by Forrest Stanley, an actor who had been cast in films such as When Knighthood Was in Flower (1922), Bavu (1923), Through the Dark (1924) and Shadow of the Law (1926). After his performance in The Cat and the Canary, Stanley played lesser roles in films such as Show Boat (1936) and Curse of the Undead (1959) and the television series Alfred Hitchcock Presents, Studio 57, and Gunsmoke.[13]

The film contained a supporting cast referred to by one film historian as "second-rate"[14] and "excellent" by another.[11] Tully Marshall played the suspicious lawyer Roger Crosby, Martha Mattox was cast as the sinister and superstitious housekeeper Mammy Pleasant, and Gertrude Astor and Flora Finch played greedy relatives Cecily Young and Aunt Susan Sillsby, respectively.[11] Lucien Littlefield was cast as deranged psychiatrist Dr. Ira Lazar who bore an eerie resemblance to Werner Krauss's title character in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari.[15]

Directing

As Universal anticipated, director Paul Leni turned Willard's play into an expressionist film suited to an American audience. Historian Bernard F. Dick observes that "Leni reduced German expressionism, with its weird chiaroscuro, asymmetric sets, and excessive stylization, to a format compatible with American film practice."[16] Jenn Dlugos argues that "many stage play movie adaptations [of the 1920s] fall into the trap of looking like 'a stage play taped for the big screen' with minimal emphasis on the environment and plenty of stage play overacting."[17] This, however, was not the case for Leni's film. Richard Scheib notes that "Leni's style is something that lifts The Cat and the Canary up and away from being merely a filmed stage play and gives it an amazing visual dynamism."[18]

Leni used similar camera effects found in German expressionist films such as The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari to set the atmosphere of The Cat and the Canary. The film opens with a hand wiping cobwebs away to reveal the title credits. Other effects include "dramatic shadows, portentous superimpositions and moody sequences in which the camera glides through corridors with billowing curtains."[3] Film historian Jan-Christopher Horak explains that a "matched dissolve from an image of the mansion and its oddly shaped towers to the oversized bottles of medicine that the dearly departed has been forced to consume functions as a double image of a prison, dwarfing the old man who sits alive with his will in a corner of the frame."[19] Leni worked with the cast to add to the mood created by lighting and camera angles. Cinematographer Gilbert Warrenton recalled that Leni used a gong to startle the actors. Warrenton mused, "He beat that thing worse than the Salvation Army beat a drum."[20]

While the film contains elements of horror, according to film historian Dennis L. White it "is structured with an end other than horror in mind. Some scenes may achieve horror, and some characters dramatically experience horror, but for these films conventional clues and a logical explanation, at least an explanation plausible in hindsight, are usually crucial, and are of necessity their makers' first concern."[21]

Besides directing, Leni was a painter and set designer. The sets of the film were designed by Leni and fabricated by Charles D. Hall, who later designed the sets of Dracula (1931) and Frankenstein (1931).[22] Leni hoped to eschew realism for visual designs that reflected the emotions of characters. He wrote, "It is not extreme reality that the camera perceives, but the reality of the inner event, which is more profound, effective and moving than what we see through everyday eyes ...."[3] Leni went on to direct the Charlie Chan film The Chinese Parrot (1927), The Man Who Laughs (1928), and The Last Warning (1929) before his death in 1929 from blood poisoning.[23]

Reception and influence

The Cat and the Canary debuted in New York City's Colony Theatre on September 9, 1927,[11][24] and was a "box office success".[19] Variety opined, "What distinguishes Universal's film version of the ... play is Paul Leni's intelligent handling of a weird theme, introducing some of his novel settings and ideas with which he became identified .... The film runs a bit overlong .... Otherwise it's a more than average satisfying feature ...."[25] A New York Times review expounded, "This is a film which ought to be exhibited before many other directors to show them how a story should be told, for in all that he does Mr. Leni does not seem to strain at a point. He does it as naturally as a man twisting the ends of his mustache in thought."[26] Nonetheless, as film historian Bernard F. Dick points out, "[e]xponents of Caligarisme, expressionism in the extreme ... naturally thought Leni had vulgarized the conventions [of expressionism]". Dick, however, notes that Leni had only "lighten[ed] [expressionist themes] so they could enter American cinema without the baggage of a movement that had spiraled out of control."[16]

Modern critics address the film's impact and influence. Michael Atkinson of The Village Voice remarks, "[Leni's] adroitly atmospheric film is virtually an ideogram of narrative suspension and impact";[27] Chris Dashiell states that "[e]verything is so exaggerated, so lacking in subtlety, that we soon stop caring what happens, despite a few mildly scary effects", although he admits that the film "had a great effect on the horror genre, and even Hitchcock cited it as an influence."[28] Tony Rayns has called the film "the definitive 'haunted house' movie .... Leni wisely plays it mainly for laughs, but his prowling, Murnau-like camera work generates a frisson or two along the way. It is, in fact, hugely entertaining ...."[29] John Calhoun feels that what makes the film both "important and influential" was "Leni's uncanny ability to bring out the period's slapstick elements in the story's hackneyed conventions: the sliding panels and disappearing acts are so fast paced and expertly timed that the picture looks like a first-rate door-slamming farce .... At the same time, Leni didn't short-circuit the horrific aspects ...."[30]

Although not the first film set in a supposed haunted house, The Cat and the Canary started the pattern for the "old dark house" genre.[31] The term is derived from English director James Whale's The Old Dark House (1932), which was heavily influenced by Leni's film,[15] and refers to "films in which murders are committed by masked killers in old mansions."[32] Supernatural events in the film are all explained at the film's conclusion as the work of a criminal. Other films in this genre influenced by The Cat and the Canary include The Last Warning, House on Haunted Hill (1959), and the monster films of Abbott and Costello and Laurel and Hardy.[33][34]

In 2001, the American Film Institute nominated this film for AFI's 100 Years...100 Thrills.[35] On Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds a rating of 93% based on 41 reviews with the consensus: "Bringing its sturdy setup thrillingly to life, The Cat and the Canary proves Paul Leni a director with a deft hand for suspenseful stories and expertly assembled ensembles."[36]

Other film versions

The Cat and the Canary has been filmed five other times. Rupert Julian's The Cat Creeps (1930) and the Spanish language La Voluntad del muerto (The Will of the Dead Man) directed by George Melford and Enrique Tovar Ávalos were the first "talkie" versions of the play; they were produced and distributed by Universal Pictures in 1930.[3] Although the first sound films produced by Universal, neither was as influential on the genre as the first film and The Cat Creeps is lost.[37]

The plot had become too familiar, as film historian Douglas Brode notes, and it "seemed likely the play would be put away in a drawer [indefinitely]."[6] Yet Elliott Nugent's film, The Cat and the Canary (1939), proved successful.[38][39] Nugent "had the inspired idea to openly play the piece for laughs."[6] The film was produced by Paramount and stars comedic actor Bob Hope. Hope plays Wally Campbell, a character based on Creighton Hale's performance as Paul Jones. One critic suggests that Hope developed the character better than Hale and was funnier and more engaging.[11]

Other film adaptations include Katten och kanariefågeln (The Cat and the Canary), a 1961 Swedish television film directed by Jan Molander and The Cat and the Canary (1978), a British film directed by Radley Metzger. The 1978 version was produced by Richard Gordon, who explained "Well, it hadn't been done since the Bob Hope version, it had never been done in colour, it was a well-known title, had a certain reputation, and it was something that logically could or in fact should be made in England."[40]

References

- ↑ Carlos Clarens, An Illustrated History of Horror and Science-Fiction Films: The Classic Era, 1895–1967 (New York: Da Capo Press, 1997), p. 56, ISBN 0-306-80800-5.

- ↑ Joan Weinstein, The End of Expressionism: Art and the November Revolution in Germany, 1918–1919 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990), p. 3, ISBN 0-226-89059-7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Richard Peterson, liner notes, The Cat and the Canary (DVD, Image Entertainment, 2005).

- ↑ Steve Neale, Genre and Hollywood (London: Routledge, 2000), p. 95, ISBN 0-415-02606-7.

- ↑ Ian Conrich, "Before Sound: Universal, Silent Cinema, and the Last of the Horror Spectaculars", in The Horror Film, ed. Stephen Price, (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 2004), p. 47, ISBN 0-8135-3363-5.

- 1 2 3 Douglas Brode, Edge of Your Seat: The 100 Greatest Movie Thrillers (New York: Citadel Press, 2003), p. 32, ISBN 0-8065-2382-4.

- ↑ Rhodes, Gary Don (2001). White Zombie. Anatomy of a Horror Film. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-4766-0491-6.

- ↑ Hans J. Wollstein, Laura La Plante biography at AllMovie Archived April 26, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved January 12, 2007.

- ↑ Robert McG. Thomas Jr. (October 17, 1996). "Laura La Plante Dies at 92; Archetypal Damsel in Distress". New York Times. p. B14.

- ↑ Hal Erickson, Creighton Hale biography at AllMovie Archived April 26, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved January 12, 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 5 John Howard Reid, These Movies Won No Hollywood Awards (Lulu Press, 2005), p. 39, ISBN 1-4116-5846-9.

- ↑ Joseph M. Curran, Hibernian Green on the Silver Screen: The Irish and American Movies (Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press, 1989), p. 27, ISBN 0-313-26491-0.

- ↑ Hans J. Wollstein, Forrest Stanley biography at AllMovie Archived April 26, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved January 12, 2004.

- ↑ Thomas Schatz, The Genius of the System: Hollywood Filmmaking in the Studio Era (New York: Owl Books, 1996), p. 89, ISBN 0-8050-4666-6.

- 1 2 Clarens, Illustrated History of Horror, p. 57.

- 1 2 Bernard F. Dick, City of Dreams: The Making and Remaking of Universal Pictures (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1997), p. 56, ISBN 0-8131-2016-0.

- ↑ Jenn Dlugos, review of The Cat and the Canary DVD, at Classic-Horror; last accessed January 4, 2007.

- ↑ Richard Scheib, review of The Cat and the Canary, at The SF, Horror and Fantasy Film Review Archived November 10, 2006, at the Wayback Machine; last accessed January 4, 2007.

- 1 2 Jan-Christopher Horak, "Sauerkraut and Sausages with a Little Goulash: Germans in Hollywood, 1927." Film History 17 (2005): pp. 241.

- ↑ Gilbert Warrenton, quoted in Kevin Brownlow, "Annus Mirabilis: The Film in 1927", Film History 17 (2005): p. 173.

- ↑ Dennis L. White, "The Poetics of Horror: More than Meets the Eye", Cinema Journal 10 (No. 2, Spring 1971): p. 5.

- ↑ John T. Soister, Up from the Vault: Rare Thrillers of the 1920s and 1930s (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 2004), p. 69, ISBN 0-7864-1745-5.

- ↑ Graham Petrie, Hollywood Destinies: European Directors in America, 1922–1931 (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2002), pp. 186–189 ISBN 0-8143-2958-6.

- ↑ "Projection Jottings", New York Times, May 15, 1927, p. X5.

- ↑ Variety review of The Cat and the Canary, quoted in Roy Kinnard, Horror in Silent Films: A Filmography, 1896–1929 (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 1995), p. 200, ISBN 0-7864-0751-4.

- ↑ Mourdant Hall, "Mr. Leni's Clever Film; 'Cat and Canary' an Exception to the Rule in Mystery Pictures", New York Times, September 18, 1927, p. X5.

- ↑ Michael Atkinson, review of The Cat and the Canary DVD, The Village Voice (New York), March 3, 2005, available here Archived November 5, 2006, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Chris Dashiell, review of The Cat and the Canary, at CineScene.com Archived December 5, 2006, at the Wayback Machine; last accessed January 4, 2007.

- ↑ Tony Rayns, The Time Out Film Guide, Second Edition, Edited by Tom Milne (London: Penguin Books, 1991), p. 106, ISBN 0-14-014592-3.

- ↑ John Calhoun, The Penguin Encyclopedia of Horror and the Supernatural, edited by Jack Sullivan (New York: Viking, 1986), p. 73, ISBN 0-670-80902-0.

- ↑ Schatz, Genius of the System, p. 88.

- ↑ Jeffrey S. Miller, Horror Spoofs of Abbott and Costello: A Critical Assessment of the Comedy Team's Monster Films (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 2004), p. 2, ISBN 0-7864-1922-9.

- ↑ Miller, Horror Spoofs, pp. 2–3.

- ↑ Joseph Maddrey, Nightmares in Red, White, and Blue: The Evolution of the American Horror Film (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 2004), p. 40, ISBN 0-7864-1860-5.

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Thrills Nominees" (PDF). Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ↑ "The Cat and the Canary (1927)". Rotten Tomatoes.

- ↑ Soister, Up from the Vault, p. 74.

- ↑ Douglas W. McCaffrey, The Road to Comedy: The Films of Bob Hope, (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 2005), pp. 28–29, ISBN 0-275-98257-2.

- ↑ Alan Jones, The Rough Guide to Horror Movies (New York: Rough Guides, 2005), p. 77, ISBN 1-84353-521-1.

- ↑ Interview with Richard Gordon, in Tom Weaver, Return of the B Science Fiction and Horror Heroes: The Mutant Melding of Two Volumes of Classic Interviews (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 2000), p. 192, ISBN 0-7864-0755-7.

Further reading

- Bock, Hans-Michael (Ed.) Paul Leni: Grafik, Theater, Film. Frankfurt am Main: Deutsches Filmmuseum, 1986. ISBN 978388799008-4

- Everson, William K. American Silent Film. New York: Da Capo Press, 1998. ISBN 0-306-80876-5.

- Hogan, David. Dark Romance: Sexuality in the Horror Film. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 1997. ISBN 0-7864-0474-4.

- MacCaffrey, Donald W., and Christopher P. Jacobs. Guide to the Silent Years of American Cinema. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1999. ISBN 0-313-30345-2.

- Prawer, S. S. Caligari's Children: The Film as Tale of Terror. New York: Da Capo Press, 1989. ISBN 0-306-80347-X.

- Worland, Rick. The Horror Film: A Brief Introduction. Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishing, 2007. ISBN 1-4051-3902-1.

External links

- The Cat and the Canary at IMDb

- The Cat and the Canary at Rotten Tomatoes

- The Cat and the Canary at AllMovie

- Stills at www.silentfilmstillarchive.com

- The Cat and the Canary (1927) on YouTube