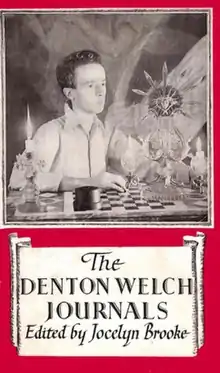

First edition | |

| Author | Denton Welch (Jocelyn Brooke, editor) |

|---|---|

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Diaries |

| Publisher | Hamish Hamilton |

Publication date | 1952 |

| Media type | Print (Hardback) |

| Pages | 268 |

| Preceded by | A Last Sheaf |

| Followed by | I Left My Grandfather's House |

The Denton Welch Journals refers to a number of works which published the notebooks of the English writer and painter Denton Welch. These he kept from July 1942 until four months before his death in 1948. To date, three versions have been issued: two published by Hamish Hamilton (1952 and 1973) and one by Viking Penguin (1984).

Background

Although published after his death, Michael De-la-Noy, in his introduction to the 1984 edition states that the "journals" title was the author's own,[1] as Welch had never intended merely to keep a daily diary.[2] As such, the notebooks include undated fragments, a substantial entry for an uncompleted novel, as well as poetry and longer prose passages (all of which were published separately). De-la-Noy observes that several of the entries seem intended as a recollection write-up for use elsewhere, potentially prompted by an anniversary or other memory-triggering event.[3] As if to emphasise their non-linear nature, the manuscripts themselves are not physically diaries but "nineteen thin, paper-covered 'school' exercise-books."[4] James Methuen-Campbell has noted that the journals (now in the Denton Welch Archive at the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin) appear to have been written "with a definite eye on posterity".[5] Having been left the invalided victim of a near-fatal collision between his bicycle and a motor car in 1935, Welch was acutely aware of his mortality, and it seems to have been rarely far from his thoughts. As he confided in a letter to his partner Eric Oliver, "I think I'm going to have a very sticky death".[6]

As might be expected from personal papers, the journals are an unvarnished depiction of the author's frailties. Welch's first biographer Robert Phillips states that they portray him,

"at his most thoroughly unprofessional, disclosing the life of a high-strung, complex, temperamental young man who, in spite of obvious gifts, is visited with... spitefulness, childishness, vanity, gloryseeking, and materialism"[7]

not to mention snobbery and callousness. In the view of Michael De-la-Noy, these undoubted shortcomings are counterbalanced by "a consistent honesty about himself" which, given the hugely challenging physical circumstances he faced, display "a perfectly justified self-indulgence".[8]

The first publication of the Journals, under the editorship of Jocelyn Brooke, came out in 1952, and was the third publication sanctioned by Welch's literary executors (after A Voice Through a Cloud (1950) and A Last Sheaf (1951)). This version was of necessity heavily edited, ultimately losing of half the overall content, because, as Brooke noted in his introduction: "... a number of the omitted passages, though not legally actionable, might well cause offence or embarrassment to the persons concerned..."[9] As Phillips adds, "[t]his is the risk one runs... in publishing the diary of a man just dead."[10] Of what is included, almost all the names of people not in Welch's immediate circle are redacted; Edith Sitwell is a notable exception.[11][12]

Phillips' comments were made in the light of the second edition of the Journals, published in 1973 and after its editor's death, which did not augment the original edition in any way. Phillips implies that some of the entries remain absent as they are "frankly homosexual" in nature.[13]

The third edition of 1984 was prompted by the discovery of additional material by the actor Benjamin Whitrow.[14] Whitrow had been corresponding with one of Welch's friends, Francis Streeten. After Streeten's death, Whitrow found amongst his belongings Brooke's typescript working copy of the journals,[15] and these he used to uncover (in some cases decipher) the material Brooke had excised.[16] This new edition completely revised the content, replacing all the redacted names, and expanding Brooke's edition by some 75,000 words[17] but not including the longer prose passages and some of the poetry (published in A Last Sheaf), and novel fragment (published as I Left My Grandfather's House in 1958).[18] However, reviewing[19] this edition, the writer Alan Hollinghurst expressed reservations about its veracity: finding errors in the extracts De-la-Noy quoted from the Journals in his biography, Hollinghurst wondered which ones were the misprints.[20][21] In his notes to his 2002 biography, James Methuen-Campbell identifies several other misprints or misreadings present in the 1984 edition.[22]

Notes and references

- ↑ Curiously, neither De-la-Noy nor Brooke elected to use the plain, innominate version of the title (Journals) for their editions, despite the author providing it.

- ↑ De-la-Noy, Michael (ed.) (1984a) The Journals of Denton Welch, Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. ISBN 9780140100938. p. x

- ↑ De-la-Noy (1984a), p. xi

- ↑ Brooke, Jocelyn (ed.) (1952) The Denton Welch Journals, London: Hamish Hamilton, p. xv

- ↑ Methuen-Campbell, James (2002) Denton Welch: Writer and Artist, Carlton-in-Coverdale: Tartarus Press ISBN 1872621600, p. 114

- ↑ Quoted in De-la-Noy, Michael (1984b) Denton Welch: The Making of a Writer, London: Viking ISBN 0670800562, p. 212

- ↑ Phillips, Robert (1974) Denton Welch, New York: Twayne, p. 148

- ↑ De-la-Noy (1984a) p. xii

- ↑ Brooke (1952) p. xiv

- ↑ Phillips (1974) p. 147

- ↑ Brooke (1952) p. 4

- ↑ Brooke had apparently intended to follow this publication with a volume of Welch's letters, as a letter in The Times Literary Supplement of 15 May 1953 indicates. According to John Russell Taylor in a December 1984 review of the revised journals in The Times, the "upset" caused by Brooke's edition caused it to be dropped, and to date a volume of Welch's collected letters is yet to be published.

- ↑ Phillips (1974) p. 147

- ↑ De-la-Noy (1984a) p. xi

- ↑ In his 1988 biography of Edward Sackville-West, Michael De-la-Noy suggests that Eric Oliver had originally entrusted editorship of the journals to Streeten; one to whom, in De-la-Noy's words, "it would have been rash to trust with a shopping list." (ISBN 9780370311647, p. 242). In a letter to Brooke, Sackville-West referred to Oliver as a "seedy nobody".

- ↑ Whitrow, Benjamin (2013) "Feverish Haste", Slightly Foxed 38, ISBN 9781906562502

- ↑ De-la-Noy (1984a) p. x

- ↑ The 1984 edition is not completely unexpurgated, however. De-la-Noy states in the introduction that "two very minor cuts have been made on the grounds of libel" with a further excision of "gratuitous gossip." (1984a, p. x)

- ↑ Hollinghurst, Alan (1984) "Diminished Pictures", Times Literary Supplement, December 21 1984, p. 1479-80

- ↑ Hollinghurst found over seventy inconsistences: as an example, in the 1984 edition of the Journals, Welch identifies his partner's aunt as "...delicate and gentle" (De-la-Noy (1984a) p. 167) whereas in the biography this is quoted as "...delicate and genteel" (De-la-Noy (1984b), p. 236)

- ↑ Jean-Louis Chevalier's overview of the Denton Welch papers at the University of Texas at Austin for the Texas Quarterly, Summer 1972, quotes a handful of passages from the journals which Brooke did not use. Even here there are inconsistencies with the 1984 publication. For instance, "golden brown" becomes "gold brown" in the 1984 edition, "verandah" becomes "veranda", "all those fifty years ago" becomes "all those years ago". These errors are all in a single journal entry and on one page. Even more critically, an entry for January 4 1944 states: "... I thought how many times I had sat in tea-shops and restaurants alone, listening to others talking, watching them, fitting into their lives, then watching them walk out of the door and away for ever." (p. 12). In the 1984 edition, De-la-Noy omits a comma, and in so doing changes the meaning: "... watching them fitting in to their lives, then watching them walk out of the door..." (1984a, p. 180).

- ↑ The tale of how the 1984 edition came into being is particularly labyrinthine: after Welch's death, his friend Helen Roeder transcribed the journals into a typewritten copy, almost certainly making errors in the process. Jocelyn Brooke used this transcription for his 1952 edition (and it appears he physically cut and pasted Roeder's work to achieve this). This heavily-edited document passed (possibly back - see note 15 above) into the hands of Francis Streeten, and thence to Benjamin Whitrow, who attempted to reconstruct the original material from what remained. De-la-Noy used this as the basis for his edition, stating that it "saved me hours of routine work" (1984a, p. xi), presumably meaning the work of verifying its accuracy with the originals in Texas.