| The Dragon Painter | |

|---|---|

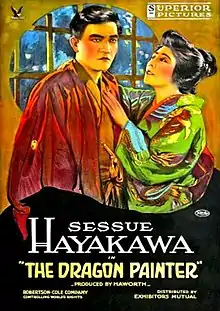

Theatrical poster | |

| Directed by | William Worthington |

| Written by | Richard Schayer |

| Based on | The Dragon Painter by Mary McNeil Fenollosa |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Frank D. Williams |

| Music by | Mark Izu, 2005 restoration |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Robertson-Cole Distributing Corporation |

Release date |

|

Running time | 53 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | silent |

The Dragon Painter is a 1919 English language silent romance drama film. It is based on the novel of the same name, written by Mary McNeil Fenollosa. It stars Sessue Hayakawa as a young painter who believes that his fiancée (played by Hayakawa's wife Tsuru Aoki), is a princess who has been captured and turned into a dragon. It was directed by William Worthington and filmed in Yosemite Valley, Yosemite National Park, and in the Japanese Tea Garden in Coronado, California.

The Dragon Painter was restored in 1988 by the American Film Institute with the George Eastman House and MoMA. In 2014, the film was added to the National Film Registry for being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[1][2][3]

Plot

Tatsu (Hayakawa) lives within the mountains of Hakawa, Japan, creating a series of paintings and disposing of them upon completion, shouting to the gods to return his fiancée, a princess who he believed was turned into a dragon. Meanwhile, in Tokyo, Kano Indara (Peil, Sr.), a famous painter, seeks a protege and heir to continue the family bloodline of master paintings.

Tatsu heads to a nearby village and demands some paper from the locals. His unusual behavior catches the attention of Uchida (Fujita), a surveyor and friend of Indara. While on a surveying expedition in the mountains, one of Tatsu's discarded paintings comes into Uchida's possession. Amazed at the artwork, Uchida invites Tatsu to Tokyo, claiming that Indara knows the whereabouts of the lost princess.

Tatsu arrives at a dinner prepared in his honor, but his wild disposition causes a ruckus. He throws a cushion and chases off other guests. Tatsu is about to leave when Indara presents a dance by the lost princess, who he explains is in the form of his only daughter, Ume-ko (Aoki). Tatsu demands Ume-ko's hand in marriage; Indara agrees on the condition that Tatsu be his son and disciple to carry on the Indara name.

Shortly after their marriage, Tatsu unable to paint, explains that ever since he found happiness, he has no reason to do so. The Indaras try to encourage Tatsu to paint but to no avail. Realizing that Tatsu's longing to find his lost princess is what granted him his ability to paint, Ume-ko tells her father that by her death, Tatsu's talent may be restored. The following morning, Tatsu discovers a letter from Ume-ko, saying that she had committed suicide in hopes that it would restore Tatsu's ability. Distraught at what has happened, Tatsu attempts suicide by drowning at a nearby waterfall, but is unsuccessful. Tatsu's sorrow continues to grow as time passes until one day he sees what appears to be Ume-ko's ghost at the family garden, which motivates him to paint once more. Tatsu's latest work gives him and the Indaras international recognition, but shortly after his success, his sorrow returns. This prompts Ume-ko, who was in hiding all the while, to return to an amazed Tatsu. The film ends with Tatsu painting in the mountains with Ume-ko by his side.

Cast

- Sessue Hayakawa as Tatsu, "Dragon painter"

- Tsuru Aoki as Ume-ko

- Edward Peil, Sr. as Kano Indara

- Toyo Fujita as Uchida

Production

The film was produced by Hayakawa's own production company Haworth Pictures Corporation and distributed by Robertson-Cole Distributing Corporation. After Hayakawa starred in the critically and commercially successful film The Cheat, Aoki's film career was restricted to playing the love interest of Hayakawa in her future films.[4] Aoki's off-screen image was that of a Japanese woman who had adapted herself to America middle class habits. Daisuke Miyao suggests in the biography of Hayakawa Sessue Hayakawa: Silent Cinema and Transnational Stardom that the name of Piel's character might have been a mixture of names of a Japanese painter Kano and Chinese painter Indara. A print of the film was restored at the George Eastman House. In the print the hero's name is Ten-Tsuou instead of Tatsu.[5] The film was publicized as showing the "exotic" Japan, its culture and landscape. An advertisement in Motion Picture World carried eight images of Hayakawa in kimono.

Reception

Japanese film theorist Daisuke Miyao wrote in his book The Oxford Handbook of Japanese Cinema that "The Dragon Painter...a Hayakawa star vehicle...was a perfect example of Aoki providing authenticity to the Orientalist imagination of Japan."[4] He further wrote "Playing the role of Ume-ko, Aoki provides a sense of authenticity to the stereotypical self-sacrificing Japanese woman like Cio-Cio-San."[6] The film was praised for successfully reproducing an authentic Japanese atmosphere. However, the Japanese film magazine Kinema Jumpo noted that the film had not shown "either contemporary or actual Japan".[4] Katsudo Kurabu, a Japanese film trade magazine, commented, "Even though Mr. Sessue Hayakawa took subject matter from Japan, Japanese styles and names in The Dragon Painter are very inappropriate...a film about Japan that does not properly depict Japanese customs is very hard to watch for us Japanese."[5] The Motion Picture World stated that Hayakawa had, "steadily advanced in popularity" and that several of the well known exhibitors had contracted for every collaboration between Hayakawa and Robertson-Cole. The film is regarded as the first in the series of "Hayakawa superior pictures" produced by Robertson-Cole.[7] Margaret I. MacDonald praised the "authentic" Japanese presentation and wrote "one of the especially fine features of the production is the laboratory work, mountain locations of extreme beauty, chosen for the purpose of imitating Japanese scenery and supplying Japanese atmosphere, are enhanced by the splendid results accomplished, in the work of developing and toning."[7]

Contemporary critics have rated the film favorably. According to New York Times review of a Hayakawa retrospective: "The film is a kind of visually sophisticated fairy tale, with tinting (best is the moonlit blue of the night scenes) and neatly composed interiors and silhouettes. Set in Japan with Japanese characters, The Dragon Painter, though written by an American, seems like a relic from a parallel Hollywood: one without the cultural and sexual fetishism that often characterized its forays into the exotic."[8]

Preservation

A 35mm print was discovered in France and was restored by the American Film Institute with the George Eastman House and the Museum of Modern Art in 1988.[9] In 2014, The Dragon Painter was deemed "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant" by the Library of Congress and selected for preservation in the National Film Registry.[10][1]

The restoration was supervised by Stephen Gong. In 1988, the restored print premiered in Little Tokyo in Los Angeles with a benshi narrator and traditional music.

The restored film was packaged with The Wrath of the Gods (1914) on DVD in March 2008.[11][12][13][14]

References

- 1 2 Gray, Tim (17 December 2014). "'Big Lebowski,' 'Willy Wonka' Among National Film Registry's 25 Selections". Variety. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

- ↑ "Complete National Film Registry Listing". Library of Congress. Retrieved 2020-06-08.

- ↑ "Cinematic Treasures Named to National Film Registry". Library of Congress. Retrieved 2020-06-08.

- 1 2 3 Miyao 2013, p. 158.

- 1 2 Miyao 2007, p. 178.

- ↑ Miyao 2013, p. 159.

- 1 2 Miyao 2007, p. 176.

- ↑ "Sessue Hayakawa: East and West, when the Twain Met".

- ↑ AFI 2015.

- ↑ LOC 2014.

- ↑ Erickson 2008.

- ↑ Sinnott, John (18 March 2018). "The Dragon Painter". DVD Talk. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

- ↑ "A new live music score sparks up 100-year-old movie 'The Dragon Painter'". BillyPenn.com. 5 November 2017. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

- ↑ King, Rachel (5 December 2016). "One of the First Hollywood Heartthrobs Was a Smoldering Japanese Actor. What Happened?". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

Bibliography

- "The Dragon Painter". Catalog of Feature Films. American Film Institute. Retrieved 2015-03-16.

- Erickson, Glenn (2008). "The Dragon Painter (1919)". Turner Classic Movies. Home Video Reviews. Retrieved 2015-03-16.

- "Cinematic Treasures Named to National Film Registry" (Press release). Library of Congress, Information Office. December 17, 2014. ISSN 0731-3527. Retrieved 2015-03-16.

- Miyao, Daisuke (2013). The Oxford Handbook of Japanese Cinema. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-973166-4.

- Miyao, Daisuke (2007). Sessue Hayakawa: Silent Cinema and Transnational Stardom. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-3969-4.

External links

- The Dragon Painter essay by Daisuke Miyao at National Film Registry

- The Dragon Painter at the American Film Institute Catalog

- The Dragon Painter at IMDb