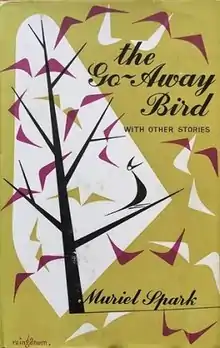

First edition | |

| Author | Muriel Spark |

|---|---|

| Original title | The Go-Away Bird with Other Stories |

| Cover artist | Victor Reinganum |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Publisher | Macmillan (UK) Lippincott (US) |

Publication date | 1958 (UK), 1960 (US) |

| Media type | |

| Pages | 215 |

The Go-Away Bird and Other Stories is the first short story collection by Scottish author Muriel Spark, first published in 1958 by Macmillan in the UK and in 1960 by Lippincott in the US.

Contents

It contains 11 stories :-

- "The Black Madonna" - Set in a new town near Liverpool, Roman Catholic couple Raymond and Lou see a lot of two Jamaican black friends, Henry and Oxford. A Black Madonna carved from bog oak in their local church becomes associated with several miracles. Childless Raymond and Lou decide to pray to it. Soon after Lou falls pregnant, they are both shocked to find the baby is black. Raymond accuses Lou of having an affair with Henry or Oxford. The couple don't believe it can be theirs and they take it up for adoption.

- "The Pawnbroker's Wife" - Set in 1942 on the Cape of Good Hope, Mrs Jan Cloote has three daughters and lives above a pawnshop where she takes in lodgers. Her husband left her some years ago and she now successfully takes charge of the shop. She periodically hosts her lodgers and talks about her pawnbroking business as her conduct seems less than honest...

- "The Twins (first published in the Norseman in 1954) - The narrator visits her schoolfriend Jennie and her husband Simon and their twins Marjie and Jeff on a couple of occasions; spread across several years. The family appears to be happy but individually the members appear to make excuses for each other when speaking to the narrator.

- "Miss Pinkerton's Apocalypse - Miss Pinkerton sees an antique saucer flying around a room. Her male friend George also sees it, though they differ about its interpretation: Miss Pinkerton sees a Spode label on it and a tiny pilot flying it, while George thinks it is radio-active. They call a reporter from a local paper to interview them but the story ends in ambiguity as they have both been drinking or maybe caused by madness...

- "A Sad Tale's Best For Winter" (the title is taken from Shakespeare's A Winter's Tale) - Selwyn Macgregor lives in a shack by a graveyard and contemplates the dead. Every month he was sent money by his Aunt who has now died, but continues via her will to provide him with his necessities. Selwyn regards whisky as his main concern, but every month his supply runs out and Selwyn withdraws without speaking to any one until his supply of whisky is replenished...

- "The Go-Away Bird" - Daphne du Toit was orphaned when she was six and grew up in her Uncle's farm in Southern Africa, where she often heard the call of the go-away bird. In the second part of the story Daphne travels to London 1946 after the war to stay with her mother's family, where she falls in love with an artist Ralph, but she finds her life to be very costly. Finally she returns to Africa to her uncle's farm...

- "Daisy Overend" - The narrator worked briefly for Daisy Overend, a political columnist and mover in literary circles. Daisy had two lovers, an expert on politics and a poet. Then at her party, Daisy left her garters in the room which led to considerable consternation, from which the narrator was dismissed the following morning.

- "You Should Have Seen the Mess" - Lorna was middle-class and grew up in a clean house, but everywhere she sees dirt and shabbyness for those that should know better and notices anything unhygienic..

- "Come Along, Marjorie" - Gloria arrives at a retreat at a Catholic Abbey in Worcestershire where the lay visitors 'recovers from nerves'. Gloria notices that Marjorie Pettigrew never speaks and begins to eat less food, eventually she is sent to a hospital in an ambulance...

- "The Seraph and the Zambesi" (won The Observer's 1951 Christmas-fiction prize[1]) - Samuel Cramer once a famous author now lived near the Victoria Falls on the Zambesi River. On Christmas Eve a Nativity Masque was to be held on Samuel's premises, but a Seraph then appeared before the performance causing a fire to spread...

- "The Portobello Road" (in Botteghe Oscure[2]) - Tells the story of Kathleen, Skinny, George and the narrator who finds a needle in a haystack; they rename her as Needle. George moves to a tobacco farm in Africa where he marries a black woman Matilda, but he only tells Needle about the marriage, asking her not to tell anyone. Later George returns to England where he intends to marry Kathleen, but Needle knows the truth so George kills her in a haystack. Needle later haunts George around Portobello Road...

Reception

Writing in the New York Times Aileen Pippett praises the collection: "They are at once spine-chilling and comical, teasing the imagination, sticking like burrs to the memory. They tell of what indubitably happened one is momentarily convinced, but in a very odd world...She communicates her special vision of the universe because she is a master of her craft, combining simple language with subtle construction and because she has perception of the reality of evil. Damnation and salvation are facts to her, and so is hocus pocus. The mixture of mischief and mystery makes her work unique."[3]

Thomas Rogers writes in Commentary about Spark: "Her chief equipment is a style that suggests neighbourhood gossip raised to art by the exercise of an economy that does not destroy the texture of petty, solid, local factuality. She tells you about her characters in a tone that applies scandal where there is none, and she employs this tone even when she is dealing with frankly supernatural events...I am able to become annoyed by tone so much at odds with the material, but when Miss Spark handles realistic subjects her potential coyness disappears and in stories like 'The Black Madonna' she illuminates a whole slice of postwar English life."[4]

References

- ↑ Lippincott, 1960 - Privately printed for the publisher Retrieved 12/12/2021.

- ↑ How The New Yorker Made Muriel Spark’s Reputation Retrieved 13/12/2021.

- ↑ New York Times, October 30, 1960, page BR4 Hocus Pocus and Salvation Are Very Real

- ↑ Commentary Volume 31, Issue 3, March 1961 pages 268-270.