First edition cover | |

| Author | Jill Dawson |

|---|---|

| Country | England |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Biographical novel |

| Published | 2009 |

| Publisher | Sceptre |

| Pages | 310 |

| ISBN | 978-0-340-93565-1 |

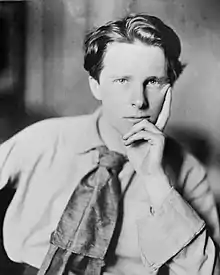

The Great Lover is a 2009 biographical novel by Jill Dawson. The novel follows the fictional Nell Golightly as she encounters the eccentric poet Rupert Brooke in Grantchester, Cambridgeshire. Set from 1909 until 1914, in the novel Dawson examines Brooke's relationship with Nell, and his growth as a poet and individual. The novel is based on the biography of Brooke during that period, incorporating opinions, ideas, and excerpts from Brooke's letters and other primary sources documenting his life.

Much of the novel emphasises Brooke's sexuality and his understanding of love. Additionally, the novel contrasts the various elements of English upper- and lower-class life during the Edwardian period. Other notable elements of the novel include the vivid descriptions of the life in Grantchester and the borrowing of themes from Brooke's poetry such as beekeeping.

Generally, reviews of the novel are positive, noting the complexity of the characterisation of both main characters and the ease which the novel communicates Brooke's life. Additionally, the novel was also featured in the 2009 Richard & Judy Summer Reads and The Daily Telegraph's "Novels of the Year" for 2009.[1][2]

Background

Rupert Brooke had a successful tenure as a student at Cambridge as a member of various prominent societies, including the Fabian Society and The Marlowe Society. When he graduated in 1909, he moved to Grantchester where he studied Jacobean drama. He eventually received a fellowship at King's College, and upon his father's death became a schoolmaster. But during this period following 1909, his personal life was very chaotic due to sexual confusion and several unsuccessful relationships with both men and women. To escape the chaos of his personal life, he toured the United States, Canada and the South Seas during 1913. Upon his return a year later, Brooke still had difficulty with relationships, however the outbreak of World War I prevented any from coming to fruition. When the War started, Brooke got a commission in the Royal Navy and wrote several of his most famous poems, a series of war sonnets. Brooke died in 1915, however, his poems were lauded by the British public, most notably Winston Churchill, and brought him to posthumous fame.[3]

Development

Dawson did biographical research in order to develop the novel. Though she is interested in writing biography, she finds that novels are an easier genre to express her understanding of the historical individual.[4][5] When writing her historical novels Dawson does not embark on a thorough bout of research beforehand, instead she researches as she writes.[4] While researching the novel, Dawson read nine biographies of Brooke, finding different elements of his life in each one, and felt that she had an additional understanding of Brooke which need to be expressed.[5][6] Dawson includes an extensive bibliography in the back of the novel showing where passages and ideas in the novel are from. She said that she included the bibliography in order to show readers where she found "[her] Rupert, a figure of [her] imagination".[7] Dawson spent so much time researching and thinking about Brooke, her husband once asked her "when is this obsession going to end?"[6]

I actually read nine biographies of Brooke and he was different in every one, so I felt I had every right to do my version. And writing a novel allows you to be more playful—and perhaps more honest about the fact this is your version of events.

— Jill Dawson[5]

Dawson's initial inspiration came from a visit to The Orchard, an inn in Grantchester where she encountered a photograph of maids who had been there while Brooke was in residence there from 1909 to 1914. The Orchard became the primary setting of The Great Lover and the maids inspired the creation of the character Nell Golightly. Dawson choose to write about Brooke because she was intrigued by his personality and why women kept falling in love with him.[7] To explore Brooke's personality, she asked herself the question "What if Rupert Brooke put a note under one of these floorboards—a note, in a way, just for me?"[5] She also was particularly interested in capturing the essence of Grantchester, the primary setting for the novel.[7]

Many elements of the novel are inspired by the works and writings of Brooke. The first and most obvious example of this is the title of the novel which is inspired by the poem of the same name.[8] The text of the poem is included at the end of the novel. Dawson chose to include the poem at the end of the book so that the reader is forced to decide if Brooke was actually a great lover, wishing the reader to be uninfluenced by the poem while she is reading the novel.[7] Nell's interest and ability with bee keeping are also a theme borrowed from Brooke's poem "The Old Vicarage, Grantchester".[8]

Plot

- Note on names: Throughout the novel Rupert Brooke is referred to as Brooke and Nell Golightly is referred to as Nell. That convention is maintained here.

The prelude of the novel begins with a 1982 letter from the elderly daughter of Rupert Brooke by a Tahitian women to Nell Golightly, asking Nell to help the daughter better understand her father. Nell responds, including a narrative of the time spent by Brooke at The Orchard in Grantchester from 1909 until his retreat in Tahiti in 1914, which becomes the rest of the novel.

Nell's story alternates between the perspectives of Nell Golightly, a seventeen-year-old girl, and the poet Rupert Brooke. The novel begins as Nell's father dies while tending to the family's bee hives. Because she is the oldest child and her mother is long dead, Nell Golightly decides finds a job as a maid at The Orchard, a boarding house and tea room outside of Cambridge which caters to the students at the University there. There she, along with several other young women, serves guests and cleans the facilities. She also helps a local beekeeper tend his hives.

Soon after Nell begins working at The Orchard, Rupert Brooke becomes a resident. As he enjoys his summer working on papers for Cambridge societies and composing his poetry, Brooke leads a social life flirting with various women and enjoying the company of artists and other students. Brooke soon lusts for Nell, and his increased interest in her leads to unconventional encounters. They develop a friendship in which both Nell and Brooke hold secret admiration and love for the other, but are unable to express it because of social conventions. Brooke also desires to lose his virginity because he feels that being a virgin is disgraceful. Because he cannot convince Nell or any of several other women to succumb to his wooing, he loses it in a homosexual encounter with a boyhood friend, Denham Russell-Smith.

After the encounter, Brooke returns home to comfort his mother at his father's death bed. After his father's death, though Brooke desires to return to the Orchard, Brooke is forced to stay at the school where his father worked as headmaster, retaining the post until the end of the school year. After a brief period, Brooke returns to The Orchard. Meanwhile, Nell's sister Betty becomes a maid at The Orchard and another of Nell's sisters has a still birth. Brooke continues to become closer to Nell, and they covertly go swimming together in Byron's pond, a local swimming hole named after the poet Lord Byron. Afterwards, Brooke departs on a tour advocating for workers' rights, which does not go very well. At the end of the tour, Brooke proposes to Noel Oliver, one of the wealthy girls whom Brooke had been courting during his stay at The Orchard. Upon his return to Grantchester, Brooke also finds himself expelled from The Orchard because of his wanton social life. Brooke then moves next door to another boarding house, the Old Vicarage.

%253B_Rupert_Brooke_from_NPG.jpg.webp)

Brooke does not marry Noel, but rather spends a brief period in Munich where he tries to become intimate with a Belgian girl in order to lose his heterosexual virginity. This relationship also fails, and he returns to England confused about his sexuality. He and Nell continue to remain close until he goes on a vacation with his friends, where he again proposes to another of his friends. Brooke is refused resulting in a psychological breakdown and an extended absence from Grantchester while he is treated by a London doctor. After a few more months, Brooke returns to the Old Vicarage briefly before departing on a trip to Tahiti via Canada and the United States. The night before he leaves, Nell realises that she still loves Brooke and goes to Brooke's bed the night before he leaves.

While in Tahiti, Brooke suffers an injury to one of his feet, and is nursed by the beautiful Taatama, a local woman. Then Brook and Taatama romance each other, eventually having sex and impregnating Taatama. After several months of exploring the island, Brooke decides to return home. Before his departure Brooke leave writes Nell a letter which contains a black pearl. Nell, now married to a local carter, receives the pearl and letter soon after she gives birth to a child by Brooke.

Characters

The novel focuses mostly on the real Rupert Brooke and the fictional Nell Golightly, although other characters, fictional and real people from Brooke's own life such as Virginia Woolf (then Virginia Stephen), are presented. Brooke's and Nell's individual character development and their relationship maintains the focus of the novel.

One reviewer noted that Brooke was depicted as so attractive that it seems that Dawson has "rather fallen for her subject".[9] However, despite his beauty and charm, the internal conflict in Brooke can be hard to sympathise with, Vanessa Curtis calling him "difficult for the reader to like" because he is "fey, brash, insecure and fickle".[10]

Nell on the other hand is a smart and responsible girl, age seventeen at the beginning of the novel. She too goes through character development. Though she expresses herself as in the control of most situations, in fact she is not, especially when Brooke is involved.[9] One reviewer noted that Nell's voice in the novel is not altogether convincing, saying "the levels of diction and spelling here seem rather high to be coming up from the kitchen".[9] The centrality of Nell in the novel was inspired by a postcard that Dawson bought which showed the maids from The Orchard during Brooke's stay.[11] Though inspired by real individuals, Nell's character primarily draws inspiration from many individuals in Dawson's own life. The name Nell Golightly is a mix of two names: Izzie Golightly, a close friend of Dawson's mother, and Nellie Boxall, Virginia Woolf's servant.[7]

Style

Dawson includes excerpts and quotes from Brooke's letters within her fictional passages, integrating both elements to create a complete narrative.[12] In fact many of the comments made by Nell observing Brooke are actually comments made by his contemporaries. This style of integrating fact and fiction is similar to Dawson's previous novel Fred and Eddie.[8] The integration of these facts is nearly seamless.[13] However, in interpreting Edwardian language, Dawson misuses the term "pump ship" according to Frances Spalding in The Independent.[13] Critic Simon Akam noted that sometimes the recreation of Brooke's language affects Nell's language, making her comments more poetic then her usual dialect.[14]

Critic Lorna Bradbury noted how many of the scenes are "wonderful", each evoking further understanding of Brooke as a character.[12] Joanna Briscoe also noted that the novel had a wonderful "sense of time and place" because it treats many elements unique to the period in the Britain very well, including Fabianism and class politics.[8] The Great Lover also maintains a very vivid imagery and sensory elements related to The Orchard; as Vanessa Curtis of The Scotsman says, "the fragrance of honey, apples and flowers suffuse the novel".[10]

Themes

Sexuality is one of the primary themes of the novel.[4] Letters by Brooke recently rediscovered by historians expressed much conflict within himself about his own sexuality. This same sexual conflict becomes a major element of Dawson's novel.[12] Nell is consistently shocked by Brooke's sexual desires and encounters throughout the novel, while at the same time Brooke is confused by his lustful desires for Nell and his desire to court sexually constrained upper-class women.[12] Brooke has other causes of internal conflict. In his search for the right person to lose his virginity to, he has a homosexual encounter almost out of desperation. The continual conflict between a desire to be loved, and the inability to find a lover is ironic when compared to the title of the novel and poem which inspired the novel: Brooke is clearly not a "great lover".[10]

Brooke's character is strongly driven by his desire to break from conventions. Brooke's unconventional actions are common throughout the novel, the most prominent being nude bathing and odd remarks and humour.[13] These actions create an externally carefree individual that is in strong contrast to the down-to-earth Nell.[10]

Social disconnect between the Edwardian upper and lower classes is also a prominent element of The Great Lover. Nell's character gives an opportunity to explore how the class structure and employment for young women of the lower classes consumed their time.[15] Brooke also commits himself to unsuccessfully campaigning against the "Poor Law".[10] Despite the treatment of class difference, Dawson does not use diction and thoughts which are convincingly lower-class in many of her lower-class characters, such as Nell, instead giving them more refined dialects.[9]

Criticism

Reviews of The Great Lover were generally positive, many of them noting the ability of Dawson to evoke the personality of Brooke and produce an accurate sense of his contemporaries and contemporary society.

Lorna Bradbury of The Daily Telegraph called the novel "a psychologically convincing picture of a man who, even in his many flirtatious moments, is teetering on the edge, and a brilliant account of the poet’s nervous breakdown."[12] Similarly, Joanna Briscoe of The Guardian said, "by the final quarter, Dawson knows what she is doing with a tricky subject, and the novel comes into its own with explosive force. It is a daring experiment, and one whose mood, setting and eccentricities linger in the mind."[8] Helen Dunmore of The Times called the narrative of the novel "strong, satisfying and memorable".[15] Vanessa Curtis of The Scotsman admired the novel for its much more satisfying portrayal of Brooke than his biographies and called it "a seductive book, evocative and well paced, the tale split between Brooke and Nell, the two narrative voices strong, distinctive and consistent."[10] Alice Ryan called the novel "a gripping and beautifully written book which deals not only with the history of Brooke and his alleged love child, but also with the wider history of the Fens, its places, people and traditions".[5] The Oxford Times critic Phillipa Logan too gave praise to the novel, saying that Dawson "exploits [the] ambiguities [in Brooke's life] to the full, creating a compelling, thoroughly plausible narrative that explores Brooke’s time as a student in Cambridge."[16] Simon Akam of The New Statesman liked the novel, noting that "in her novel Dawson has [...] pulled off the risky gamble of reimagining history."[14] The New Zealand Listener said, "The Great Lover is proof that its author is one of the finest practitioners of the literary historical novel and that this is her best novel yet."[17]

Thomas Mallon of The Washington Post, unlike other reviewers, gave a much more lukewarm assessment of the novel. He wrote, "The Great Lover is conscientious and good-hearted, but for all its class-crossing improbability, still rather timid." For Mallon, the novel does not treat Brooke during his most interesting part of his life: during the first World War, when he becomes a public figure.[9]

References

- ↑ White, Richard (4 June 2009). "Jill Dawson, Richard & Judy and The Great Lover". Norwich Writing Center. Retrieved 7 June 2011.

- ↑ Bradbury, Lorna (28 November 2009). "Novels of the year: Lorna Bradbury delves into the best of a notably fine year for fiction". The Telegraph. London. Retrieved 10 June 2011.

- ↑ "Brooke, Rupert Chawner". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/32093. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- 1 2 3 Self, John. "Watch her re-appear: Jill Dawson Interview". The Blurb (100). Retrieved 1 July 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ryan, Alice (20 February 2011). "Jill takes novel look at poet's love". Cambridge-News.co.uk. Retrieved 9 June 2011.

- 1 2 Pellegrino, Nicky (9 May 2010). "Dead poet's society". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 1 July 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Jayne. "Jill Dawson 2009 on 'The Great Lover'". BFKbooks. Retrieved 8 June 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Briscoe, Joanna (7 February 2009). "South Sea trouble: Joanna Briscoe enjoys a daring novelisation of Rupert Brooke's trysts and travels to Tahiti". The Guardian. Retrieved 6 June 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Mallon, Thomas (19 August 2010). "Jill Dawson's novel about Rupert Brooke, "The Great Lover"". Washington Post Book World. Retrieved 8 June 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Curtis, Vanessa (1 February 2009). "Book Review: The Great Lover". The Scotsman. Retrieved 9 June 2011.

- ↑ Parker, Peter (1 February 2009). "The Great Lover by Jill Dawson". The Sunday Times. Retrieved 8 June 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bradbury, Lorna (20 January 2009). "The Great Lover by Jill Dawson: Jill Dawson's dark portrait of Rupert Brooke captivates Lorna Bradbury". The Telegraph. London. Retrieved 6 June 2011.

- 1 2 3 Spalding, Frances (23 January 2009). "The Great Lover, By Jill Dawson". The Independent. Retrieved 7 June 2011.

- 1 2 Akam, Simon (5 February 2009). "Mad about the boy". The New Statesman. Retrieved 10 June 2011.

- 1 2 Dunmore, Helen (16 January 2009). "The Great Lover by Jill Dawson". The Times. Retrieved 7 June 2011.

- ↑ Logan, Philippa (24 September 2009). "Stories of different worlds". The Oxford Times. Retrieved 10 June 2011.

- ↑ Harvey, Siobhan (28 March 2009). "Beyond the myth". The New Zealand Listener. No. 3594. Retrieved 10 June 2011.