| The Morals of Hilda | |

|---|---|

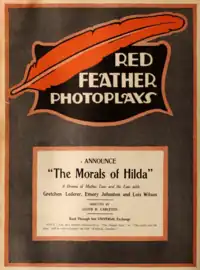

Lobby Card | |

| Directed by | Lloyd B. Carleton |

| Written by | Henry Christeen Warnack |

| Screenplay by | Anthony Coldeway |

| Produced by | Universal Red Feather Photoplays |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Roy H. Klaffki |

| Distributed by | Universal |

Release date |

|

Running time | 5 reels 50–75 minutes[lower-alpha 1] |

| Country | United States |

| Languages |

|

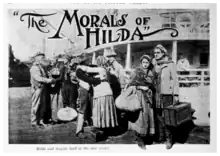

The Morals of Hilda is a 1916 American silent film directed by Lloyd B. Carleton. The melodrama is based on the story of Henry Christeen Warnack and features Gretchen Lederer, Lois Wilson and Emory Johnson.

August and Hilda were living together while saving money to get married. In their country, it did not discourage living arrangements like theirs. Since finding work was difficult in their village, they immigrated to America. American values challenged them by asserting that only wed couples can live together and have children. Seeking employment, Hilda secures a position as a domestic, while August has trouble. Hilda discovers she is pregnant. A desperate August goes to sea and dies in a shipwreck.

Hilda gives birth to a baby boy but becomes distraught upon learning of August's fate. Realizing she cannot support the child alone, she sets the boy adrift in the sea. Fate steps in, and Hilda's former employer, Ester, finds and adopts the boy. Hilda secretly watches her son grow up and seek a career in politics. In the end, she makes the ultimate sacrifice for her son.

Universal released the Red Feather Photoplay on December 11, 1916.[1]

Plot

August and Hilda were simple peasants living together, desperate to wed and start a new family. In the "old country," a man does not marry until he has saved money to support his new family. Since August cannot find work in the village, he cannot earn enough money to consider marriage. They resolve they must move to America. After they arrive, the couple finds a home, and August seeks a job. August has trouble finding work because he has no vendible skills. Another challenge faces the couple in America, people frown upon unmarried couples living together, and August fears incarceration.

Hilda finds work as a domestic for Harris Grail and his wife, Ester. She discovers the Grails cannot have children. Then, Hilda finds she is expecting a child. Realizing Hilda's condition, the Grails learn Hilda is unmarried and living with her boyfriend. The wealthy couple can't have an unwed mother living in their household and ask her to resign from her position. Hilda didn't understand the decision of her puritanical hosts. Even though she is distraught, she does not want to burden August with this load. Hilda leaves August and strikes out on her own.

Soon, she finds herself in the hospital giving birth to a healthy boy. The law states that nurses must register a newborn's parentage. The nurses ask the father's name, and Hilda refuses. Hilda's only option was to escape the hospital under cover of night. She returns home but finds the cottage empty. She assumes the worst, but unbeknownst to Hilda, August had stowed away on a tramp steamer heading for Europe. Hilda's situation is desperate, and she wants to meet death, letting the fates determine her son's future. Hilda places the baby boy in a basket, sets it afloat, then heads off to another part of the sea.

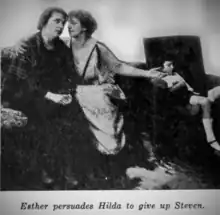

We discover that someone has murdered Ester's beloved husband - Harris Grail. Ester finds herself alone and childless and loses the will to live. Ester heads to the sea, determined to drown herself. While wandering the shore, she finds a baby floating in a basket. Ester decides to raise the boy as her own. She names the boy Steven. But Ester is alone and unable to raise the boy without help. She asked Hilda to return to service and become a nurse. Hilda accepts the offer, then discovers Steven is her abandoned baby. Hilda must keep her relationship with the baby a secret. Unable to help raise a boy she mothered, Hilda leaves Ester's service.

The years pass, and Hilda can't bear to be without her son. She returns to Ester's house and confronts Ester with the truth about being Steven's mother. They talk, and Ester convinces Hilda the boy should stay with her. In that way, Steven would have all the advantages that wealth offers. Hilda agrees, Steven will stay with Ester, and Hilda's motherhood will remain a secret.

Steven grows into adulthood and becomes an educated, articulate man. After consulting with his sweetheart, Marion, he runs for governor. Ester doesn't want Steven to have skeletons in the closet, so she tells him about his adoption. Steven reacts by creating a new plank on his political agenda, legitimizing all children of questionable parents. Since his ancestry is suspicious, he chooses not to propose marriage to the lovely Marion.

Steven wins the election and schedules an outdoor inauguration. Hilda reads about the event in the local newspaper and plans to attend. Steven is speaking to the crowd, highlighting his platform on underprivileged children. Suddenly, Hilda sees someone in the group with a gun. She believes the man is attempting to assassinate her son. Hilda rushes towards her son as the assassin fires a shot. Hilda jumps in front of her son at the last moment and takes the bullet.

After the crowd subdues the assassin, Steven rushes to the woman's side. As she lies dying, she tells Steven she is his birth mother. Hilda dies while her head rests in Steven's lap. Marion, who is nearby, consoles Steven and tells him his background doesn't matter to her. She loves him, and they can wed.

Cast

Actor Role Gretchen Lederer Hilda

Emory Johnson Steven Lois Wilson Marion Frank Whitson August Richard Morris Harris Grail Adele Farrington Esther Grail Helen Wright unknown

Production

Pre-production

In the book "American Cinema's Transitional Era," the authors point out, The years between 1908 and 1917 witnessed what may have been the most significant transformation in American film history. During this "transitional era," widespread changes affected film form and film genres, filmmaking practices and industry structure, exhibition sites, and audience demographics.[2] One aspect of this transition was the longer duration of films. Feature films[lower-alpha 2] were slowly becoming the standard fare for Hollywood producers. Before 1913, you could count the yearly features on two hands.[5] Between 1915 and 1916, the number of feature movies rose 2 ½ times or from 342 films to 835.[5] There was a recurring claim that Carl Laemmle was the longest-running studio chief resisting the production of feature films.[6] Universal was not ready to downsize its short film business because short films were cheaper, faster, and more profitable to produce than feature films. [lower-alpha 3]

Laemmle would continue to buck this trend while slowly increasing his output of features. In 1914, Laemmle published an essay titled - Doom of long Features Predicted.[8] In 1915, Laemmle ran an advertisement extolling Bluebird films while adding the following vocabulary on the top of the ad.[lower-alpha 4]

Universal released ninety-one feature films in 1916[10] including fifty-four Bluebird films.[11][lower-alpha 5]

Casting

- Adele Farrington (Mrs. Hobart Bosworth) (c. 1867-1936) was 49 years old when she portrayed Esther Grail. She was also a Universal contract player appearing in 74 films between 1914 and 1926. Although she got her start in movies when she was 47 years old (1914), Universal cast her mostly in character leads. Many of her roles were acting alongside her husband, Hobart Bosworth, who married in 1909 and divorced in 1920. In addition to her role as an actress, she was also a music composer and writer.

- Emory Johnson (1894-1960) was 22 years old when he acted in this movie as Steven. In January 1916, Emory signed a contract with Universal Film Manufacturing Company. Carl Laemmle of Universal Film Manufacturing Company thought he saw great potential in Johnson, so he chose him to be Universal's new leading man. Laemmle hoped Johnson would become another Wallace Reed. He planned to create a movie couple that would sizzle on the silver screen. Laemmle thought Dorothy Davenport and Emory Johnson could make the chemistry he sought. Johnson and Davenport would complete 13 films together. They started with the successful feature production of Doctor Neighbor in May 1916 and ended with The Devil's Bondwoman in November 1916. Johnson would make 17 movies in 1916, including six shorts and 11 feature-length Dramas. 1916 would become the second-highest movie output of his entire acting career. Emory acted in 25 films for Universal, mostly dramas with a sprinkling of comedies and westerns.

- Gretchen Lederer (1891-1955) was a 25 year-old actress when she landed this role as Hilda. Lederer was a German actress getting her first start in 1912 with Carl Laemmle. At the time of this film, she was still a Universal contract actress. She had previously acted in two Bosworth-Johnson projects preceding this movie - The Yaqui and Two Men of Sandy Bar. She had previously united with Emory Johnson in the 1916 productions of A Yoke of Gold.

- Richard Morris (1862-1924) was a 54 year-old actor when he played Harris Grail. He was a character actor and former opera singer known for Granny (1913). He would eventually participate in many future Johnson projects, including In the Name of the Law (1922), The Third Alarm (1922), The West~Bound Limited (1923), The Mailman (1923), The Spirit of the USA (1924) until his untimely death in 1924.

- Frank Whitson (1877-1946) was a 39 year-old actor when he played August. He appeared in 66 films between 1915 and 1937. This was one of his early efforts, and he would become more widely known later in his acting career.

- Helen Wright (1868-1928) was 48 years old when she acted in this movie. Helen Wright (born Helen Boyd) was a well-known Universal character actress who appeared mostly in silent films between 1915 and 1930. She spent most of her career under contract at Universal.

Director

Lloyd B. Carleton (circa|1872 - 1933) was born in New York City, New York, sometime in 1872. He was 44 years-old when he directed this film. Carleton started working for Carl Laemmle in the Fall of 1915.[14] Carleton arrived with impeccable credentials, directing sixty films for Thanhouser, Lubin, Fox, and Selig.[15] Between March and December 1916, Carleton directed seventeen movies for Universal, starting with The Yaqui and ending with this film. Ten of Carleton's 1916 Universal productions were feature films; the remaining seven were two and three-reel short films.

Emory Johnson acted in sixteen of these Carleton films, including ten features and six shorts. A major part of Carlton's 1916 output was the thirteen films pairing Dorothy Davenport and Emory Johnson. Carl Laemmle wanted his best director to create the necessary screen chemistry, which, if successful, would convert into increased box office earnings. The screen pairing is explained in the Emory Johnson part of the Casting section of this article.

After finishing this film, Carleton would sever his affiliations with Universal. He died in New York on August 8, 1933 (age 61)

Themes

Movie themes are the underlying ideas or concepts explored throughout the film.

This film has one overriding theme. A mother's love is the bedrock upon which this film stands. We know the bond between mother and son is one of the most potent forces in the world. A mother's love for her child is a special relationship built on love, trust, and respect. The bond intensifies as the participants age. By abandoning her child, Hilda could not assist her son in his personal growth and maturation into adulthood. Unable to overcome her guilt, she is more than willing to sacrifice herself for her son.

A subordinate issue is people view suicide as a perplexing and taboo topic. Hilda and Ester contemplated suicide after experiencing intense grief, guilt, anger, and confusion. However, since either party performed the deed, it did not warrant further exploration.

One reviewer proposed that theater operators allocate some promotional time to emphasize recognizing the legitimacy of all children of questionable parentage. He states " You can arouse considerable interest in this by advertising along these lines: ‘Do you believe the State should recognize motherhood and make every child legitimate, providing the mother certifies the father’s name in the probate court?' ” Despite the complexity and controversy of the issue, few media reviewers have mentioned this suggested theme. They only briefly considered the issue toward the movie's end, not enough to make it a prominent idea.[16][17]

Screenplay

Anthony Coldeway (1887 – 1963) was a prolific American screenwriter, storyteller, and director. He was only 29 years old when he wrote the scenario for this film. Coldeway created his first scenario for Pathé in Aug 1911. The film was a western 2-reeler named The Flaming Arrows. By the time of this release, he had written scenarios for over forty films. Although most of his scripts were for short films, he had created scripts for three feature-length comedies before this release.They nominated him for an Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay at the 1928 1st Academy Awards for the film Glorious Betsy.[18]

Henry Christeen Warnack (alternative H. C. Warnack) (1877 – 1927) was 39 years old when he wrote the story for this film. Warnack had spent most of his career as a newspaper reporter before moving to Los Angeles in 1907. He became the dramatic department editor of the Los Angeles Times. Warnack also became an author, composing essays, books, movie stories, and scenarios.[19]

Post production

Post-production is a crucial step in filmmaking, transforming the raw footage into the finished product. It requires skilled professionals working together to create a film that meets the director's vision and engages audiences.

The movie theater release of this film comprised five reels or roughly five thousand feet of film. The average time per reel is between ten and fifteen minutes. As a result, they estimated the total time for this movie to be between fifty and seventy-five minutes.[20] The Wid's Film and Film Folk film critic stated the full duration of the film was fifty-eight minutes.[16]

Studios

The interiors were filmed in the studio complex at Universal Studios located at 100 Universal City Plaza in Universal City, California. Universal produced and distributed this film.[1]

Release and reception

Official release

The United States Copyright Office registered the copyright for this film on December 6, 1916.[lower-alpha 6]

The official release date was December 11, 1916.[1]

Advertising

Universal's trade journal, The Moving Picture Weekly, contains an advertising section titled - PUTTING IT OVER. The section would give exhibitors suggestions for advertising selected movies. The December 2, 1916 issue had the following advertising suggestions for this movie:

The Red Feather for December eleventh is a wonderful picture and tells the story of the effect of our uncomprehended laws on the immigrants who flock to our country. You could not advertise this great feature more effectively than by dressing a pair, a young man and a young woman, in typical immigrant clothes. The woman should wear a short skirt, with an apron over it, and a three-cornered handkerchief of bright color tied over her hair. Put wooden shoes, or heavy man's shoes of some kind, on her feet and a bright-colored shawl around her shoulders. The man should wear a shabby, shapeless suit, heavy shoes on his feet, and a woolen scarf around his neck. He should carry a big bundle. On his back, he may wear a placard advertising the picture. They should walk through the streets, bewildered and lost-looking, staring at the building, and acting as two peasants from a far land, would behave in a strange country. The picture is called "The Morals of Hilda."[22]

Reviews

Movie reviews were critical opinions for theater owners and fans. Critiques of movies printed in different trade journals were vital in determining whether to book or watch the movie. Movie critics' evaluations of this film were mixed. When critics have divergent reviews, deciding whether to see or book the movie can be challenging, especially since mixed reviews do not mean it is a bad movie. In the end, it boils down to personal choices and how much value you place in the movie review and the reviewer.

| | |

|---|---|

| Term | Definition |

| Heart- *tugging *wrenching | One's deepest emotions or inner feelings. to tug at one's heartstrings |

| Histrionics | Exaggerated, overemotional behavior, especially when calculated to elicit a response; melodramatics |

| Hokum | (An instance of) excessively contrived, hackneyed, or sentimental material in a film |

| Mawkish | Excessively or falsely sentimental; showing a sickly excess of sentiment. |

| Meller | A melodrama. |

| Melodrama | A drama abounding in romantic sentiment and agonizing situations, with a musical accompaniment only in parts that are especially thrilling or pathetic. |

| Pathos | The quality or property of anything which touches the feelings or excites emotions and passions, especially that which awakens tender emotions, such as pity, sorrow, and the like; contagious warmth of feeling, action, or expression; pathetic quality. |

| Pretentious | Marked by an unwarranted claim to importance or distinction |

| Sappy | Excessively sweet, emotional, nostalgic; cheesy; mushy. |

| Sentiment Sentimental | Feelings, especially tender feelings, as apart from reason or judgment, or of a weak or foolish kind |

| Tearjerker Tearful | An emotionally charged film, novel, song, opera, television episode, etc., usually with one or more sad passages or ending, so termed because it suggests one is likely to cry during its performance |

| Weepie | A sad or sentimental film, often portraying troubled romance, designed to elicit a tearful emotional response from its audience. |

| All definitions were derived from the online Wiktionary – the free standard dictionary | |

In the December 16, 1916 issue of the Motion Picture News, Peter Milne writes:[23]

As The Morals of Hilda is based on a situation that always fails to convince, the entire picture is of an unconvincing nature. A couple from some "old country" migrate to America without first having gone through the formality of a marriage ceremony. In their country, there were no marriage laws. Passing over the fact that all countries have marriage rituals of some sort or another, it seems rather peculiar that the pair should have rebelled at having their union legalized in America. Licenses aren't very expensive.

In the December 16, 1916 issue of The Moving Picture World, the reviewer states:[24]

The Morals of Hilda is an exceptionally strong screen play which teaches a vigorous moral without sermonizing, and the story has wide appeal and is particularly suited for women. The settings and photography are up to the high standard demanded In Red Feather productions.

In the December 21, 1916 issue of Wid's Film and Film Folk, the reviewer states:[16]

There were a number of very beautifully photographed exteriors, this being particularly true of the surf scenes and a few exteriors when the son was about five years of age. The general atmosphere of the offering lacked artistic distinction, however, and many ordinary lightings brought the general tone of the production down to that of average features. The players all tried hard, but never at any time did they reach dramatic heights, the unconvincing situations making most of their attempts to act fail to reach the mark.

Preservation status

Many silent-era films did not survive for reasons as explained on this Wikipedia page.[lower-alpha 7]

According to the Library of Congress website, this film has a status of - No holdings located in archives; thus, it is presumed all copies of this film are lost.[27]

Gallery

.jpg.webp) Gretchen Lederer

Gretchen Lederer

Hilda Emory Johnson

Emory Johnson

Steven_by_Edwin_Bower_Hesser.jpg.webp) Lois Wilson

Lois Wilson

Marion.jpg.webp) Richard Morris

Richard Morris

Harris Grail Adele Farrington

Adele Farrington

Esther Grail

Lloyd B. Carleton

Lloyd B. Carleton

Director

Notes

- ↑ Runtime depends on projection speed ranging 16 to 24 frames per second

- ↑ A "feature film" or "feature-length film" is a narrative film (motion picture or "movie") with a running time long enough to be considered the principal or sole presentation in a commercial entertainment program. A film can be distributed as a feature film if it equals or exceeds a specified minimum running time and satisfies other defined criteria. The minimum time depends on the governing agency. The American Film Institute[3] and the British Film Institute[4] require films to have a minimum running time of forty minutes or longer. Other film agencies, e.g.,Screen Actors Guild, require a film's running time to be 60 minutes or greater. Currently, most feature films are between 70 and 210 minutes long.

- ↑ " Short Film" - There are no defined parameters for a Short film except for one immutable rule -the film's maximum running time. The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences defines a short film as "an original motion picture that has a running time of 40 minutes or less, including all credits".[7]

- ↑ The moving picture business is here to stay. That you must admit despite carping critics and blundering sore-heads, true, some exhibitors have found business so good lately — but if you get down to facts when you look for a reason why, it's a 100 to 1 shot that they are, and for some time have been, dallying with a feature program. Some of these wise ones will tell you that business has picked up since they went into features, — BUT — ask them whether they are talking NET or GROSS. They will find they have an immediate appointment and terminate your queries unceremoniously. Funny how we like to kid ourselves, isn't it? The man who is packing 'em in and losing money on features is envied by his competitor, who is laying by a bit every day, and has a good steady, dependable patronage but admits to a few vacant seats at some performances. When this chap wakes up, he will realize that he has a gold mine and that good advertising will make it produce to capacity. The moral is that if you can tie up to the Universal Program, DO IT. If you can't NOW, watch your first chance. Let the people know what you have, and let the feature man go on to ruin if he wants to. You should worry!

Motion Picture News - May 6, 1916[9] - ↑ What is Universal Branding — Major film studios owned many movie houses. This enabled them to have guaranteed outlets for their products. Since Universal-owned no theaters, they needed a solution advising exhibitors on the type of movie they received. Universal responded by forming a three-tier branding system for their films based on the size of their budget and status. In the book "The Universal Story," Hirschhorn describes the branding as "the low budget, Red Feather programmers, the more ambitious Bluebird releases, and the occasional Prestige or Jewel production." [12]

The ticket-buying audience he serviced went to the movies to see their favorite stars, not the vehicle allowing them to perform.[13] The branding system had a brief existence and by 1920 had faded away. - ↑ The final copyright listing was entered into the record as shown:

- THE MORALS OF HILDA. Red Feather.

1916. 5 reels.

Credits: Director, Lloyd B. Carleton; story

H. C. Warnack; scenario, A. W. Coleway.

© Universal Film Mfg. Co., Inc.; 6 Dec16;

LP9670[21]

- THE MORALS OF HILDA. Red Feather.

- ↑ Film is history. With every foot of film lost, we lose a link to our culture, the world around us, each other, and ourselves. – Martin Scorsese, filmmaker, director NFPF Board[25]

A report by Library of Congress film historian and archivist David Pierce estimates that:

References

- 1 2 3 The Morals of Hilda at the American Film Institute Catalog

- ↑ Keil & Stamp 2004, p. 1.

- ↑ "AFI-FAQ". afi.com. American Film Institute. Retrieved November 23, 2022.

- ↑ "FAQ". bfi.org.uk. British Film Institute. Retrieved November 24, 2022.

- 1 2 Keil & Stamp 2004, p. 80.

- ↑ Brouwers, Anke (July 4, 2015). "Only Whoop Dee Do Songs. Bluebird Photoplays Light(en) Up the Cinema Ritrovato — Photogénie". Cinea. Archived from the original on April 11, 2022. Retrieved November 19, 2022.

- ↑ "Rule Nineteen: Short Film's Awards". AMPAS. Retrieved November 25, 2022.

- ↑ "Doom of long Features Predicted". Moving Picture World. New York, Chalmers Publishing Company. July 11, 1914. p. 185. Archived from the original on August 9, 2011. Retrieved February 25, 2023.

written by Carl Laemmle

- ↑ "The Universal Program". Motion Picture News. Motion Picture News, inc. May 6, 1916. p. 2704. Retrieved February 7, 2021.

- ↑ Hirschhorn 1983, pp. 22–23.

- ↑ Cooper 2010, p. 23.

- ↑ Hirschhorn 1983, p. 13.

- ↑ Stanca Mustea, Cristina (June 8, 2011). "Carl Laemmle (1867 - 1939)". Immigrant Entreprenuership. German Historical Institute. Retrieved November 10, 2022.

- ↑ "CARLETON, Lloyd B." www.thanhouser.org. Thanhouser Company Film Preservation. March 1994. Retrieved February 19, 2021.

Thanhouser Company, Thanhouser Films: An Encyclopedia and History Version 2.1 by Q. David Bowers,Volume III: Biographies

- ↑ Wikipedia Lloyd Carleton page

- 1 2 3 "UNCONVINCING ACTION MELO WITH GOOD REFORM IDEA". Wid's Films and Film Folk. New York, Wid's Films and Film Folks, Inc. December 16, 1916. p. 935. Archived from the original on February 5, 2021. Retrieved February 28, 2023.

- ↑ "Universal Film Mfg., Specials – The Morals of Hilda". Moving Picture World. New York, Chalmers Publishing Company. December 16, 1916. p. 1660. Archived from the original on June 29, 2015. Retrieved March 3, 2023.

There are some strong situations in this, but some of them are unpleasant and not altogether convincing. The question raised at the close concerning the status of illegitimate children is interesting but seemed more like special propaganda than a part of the story itself.

- ↑ "The 1st Academy Awards Memorable Moments". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. August 27, 2014. Retrieved June 29, 2021.

- ↑ "H. C. Warnack, Writer, Dies". The Los Angeles Times. November 3, 1927. Retrieved June 26, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

Nationally known newspaperman, Poet, and Author Formerly Was Editor of "Times" Dramatic Department

- ↑ Kawin 1987, p. 46.

- ↑ "Catalog of Copyright Entries Cumulative Series Motion Pictures 1912 - 1939". Internet Archive. Copyright Office * Library of Congress. 1951. p. 571. Retrieved April 28, 2021.

Motion Pictures, 1912-1939, is a cumulative catalog listing works registered in the Copyright Office in Classes L and M between August 24, 1912 and December 31, 1939

- ↑ "PUTTING IT OVER". The Moving Picture Weekly. New York, Motion Picture News, Inc. December 2, 1916. p. 3864. Retrieved June 26, 2021.

A DEPARTMENT OF ADVERTISING SUGGESTIONS FOR THE BENEFIT OF ALL EXHIBITORS

- ↑ "The Morals of Hilda". Motion Picture News. New York, Motion PictureNews. December 16, 1916. p. 3864. Archived from the original on June 29, 2015. Retrieved March 3, 2023.

REVIEWED BY PETER MILNE

- ↑ "Red Feather Leads Universal's Week". Moving Picture World. New York, Chalmers Publishing Company. December 16, 1916. p. 1667. Archived from the original on June 29, 2015. Retrieved March 3, 2023.

The Morals of Hilda, featuring Lois Wilson is scheduled for December 11

- ↑ "Preservation Basics". filmpreservation.org. Retrieved December 16, 2020.

Movies have documented America for more than one hundred years

- ↑ Pierce, David. "The Survival of American Silent Films: 1912-1929" (PDF). Library Of Congress. Council on Library and Information Resources and the Library of Congress. Retrieved November 18, 2020.

- ↑ The Library of Congress American Silent Feature Film Survival Catalog: The Morals of Hilda (motion picture)"

Bibliography

- Cooper, M.G. (2010). Universal Women: Filmmaking and Institutional Change in Early Hollywood. Women and film history international. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-03522-7. Retrieved February 22, 2023.

- Hirschhorn, Clive (1983). The Universal Story (1st ed.). New York: Crown Publishers. p. 400. ISBN 0-517-55001-6.

The Complete History of the Studio and its 2,641 Films

- Kawin, Bruce F. (1987). How Movies Work. University of California Press. p. 46. ISBN 9780520076969.

- Keil, C.; Stamp, S. (2004). American Cinema’s Transitional Era: Audiences, Institutions, Practices. ACLS Humanities E-Book. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-24027-8. Retrieved July 18, 2023.

- Slide, Anthony (2000). Nitrate Won't Wait: History of Film Preservation in the United States. McFarland. p. 5. ISBN 978-0786408368. Retrieved March 25, 2013.

It is often claimed that 75 percent of all American silent films are gone, and 50 percent of all films made before 1950 are lost, but such figures, as archivists, admit in private, were thought up on the spur of the moment, without statistical information to back them up.

- Slide, Anthony (September 27, 2002). Silent Players: A Biographical and Autobiographical Study of 100 Silent Film Actors and Actresses. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-2249-6.

- Zmuda, Michael (2015). The Five Sedgwicks: Pioneer Entertainers of Vaudeville, Film, and Television. McFarland. p. 262. ISBN 978-0-7864-9668-6. Retrieved November 4, 2022.

External links

- The Morals of Hilda at AllMovie

- The Morals of Hilda at IMDb

- The Morals of Hilda at the TCM Movie Database

- Official website – Movie history by Film Historian Tom Dirks

- List of Universal Pictures films (1912–1919)

- Universal Pictures

- List of American films of 1916