| The Norman Tower | |

|---|---|

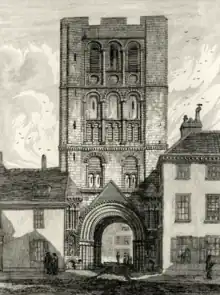

The Norman Tower from the east, with the cathedral to the right | |

The Norman Tower Location in Suffolk | |

| 52°14′37″N 0°43′00″E / 52.24367°N 0.71669°E | |

| Location | Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk, England |

| Architecture | |

| Heritage designation | Grade I |

| Style | Romanesque |

| Years built | 1120-1148 |

| Specifications | |

| Width | 36 feet (11 m) |

| Height | 86 feet (26 m) |

| Bells | 12 + flat sixth + service |

| Tenor bell weight | 27 long cwt 2 qrs 5 lbs (3,085 lb or 1,399 kg) |

The Norman Tower, also known as St James' Gate,[1] is the detached bell tower of St Edmundsbury Cathedral, Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk. Originally constructed in the early 12th century, as the gatehouse of the vast Abbey of Bury St Edmunds, it is one of only two surviving structures of the Abbey, the other being Abbey Gate, located 150 metres to the north.[2][3] The Abbey itself lies in ruins, approximately 200 metres to the east.[3] As a virtually unaltered structure of the Romanesque age, the tower is both a Grade I listed building and a Scheduled Ancient Monument.[4] The tower is considered amongst the finest Norman structures in East Anglia.

History

Medieval era

The tower was constructed under the auspices of Anslem, Abbot of Bury St Edmunds, from 1120 to 1148 as the principal gateway into the abbey.[2][4][5][6] The abbey at this time was one of the largest medieval churches in Europe, being more than 500 feet (150 m) in length, and 240 feet (73 m) wide at its western end.[7] Two other churches were built in the medieval period within the grounds of the abbey, the Church of St Denis, and the Church of St Mary.[8]

The Church of St Denis was rebuilt in 1135 as the Church of St James, later to become St Edmundsbury Cathedral, and was located a stone's throw from the walls of the tower. Both churches were rebuilt several times in the ensuing centuries, but little changed with the tower until the Dissolution of the Monasteries.[8]

The abbey was dissolved by order of Henry VIII in 1539 and from this point on, the tower's primary purpose was now as the bell tower for the Church of St James, which had no tower of its own. Ruins of the eastern end of the abbey still survive behind the present cathedral, as does a portion of the west front, known as Sampson's Tower. Sometime post-dissolution, the ground around the church was raised to prevent flooding, and as such the tower now sits nearly 6 feet below street level.[6][7][8]

18th and 19th centuries

Other than the removal of the tympanum from the western face of the tower in 1798,[4][6] the tower continued to keep its original appearance into the early 19th century. However, by 1809, concerns became widespread about the structural integrity of the tower, influenced by a report in the Bury and Norwich Post. The report suggested removing the bells in the tower to St Mary's Church, as the ringing of the bells was believed to have been the cause of the dangerous state of the tower. The report's suggestions were not carried out.[9]

At a meeting of the parish of St James on 6 April 1811, it was decided that a local architect, Mr Patience, should be entrusted to put a new roof on the tower. The estimated cost was £260. The work of stripping the existing lead from the roof began immediately but on 15 April, for reasons that are not recorded, Mr Patience was stripped of his contract. The tower was therefore left open to the elements. James Tompson, a local carpenter, was ordered by the churchwardens to complete the work originally left to Mr Patience, and his work would be valued by two local builders upon completion before he was to be paid. The work was completed in December 1811, but Tompson would not be paid for several years and took the parish to court as a result.[9]

Partial collapse and restoration

Following ringing on 5 November 1818, part of the eastern face of the gateway arch collapsed, leading to massive cracks appearing in the tower, stretching virtually the entire height of the structure. The ringing of the bells was again blamed. Despite the apparent seriousness of the situation, reports in The Gentleman's Magazine indicated that the cracks were plastered up and ringing resumed.[9]

Concerns returned in 1840 when the churchwardens asked visiting architect William Ranger for an opinion. His report, presented in the July of that year, stated that whilst the damage was repairable, it could be made worse by the ringing of the bells. It is not recorded whether the bells were silenced immediately, but a report in the Bury and Norwich Post in August 1842 said the bells should not be rung. The report followed an inspection by Lewis Nockalls Cottingham who spent more than a week examining the tower, including the removal of the plaster erected in 1818 so he could see the full extent of the damage.[4][6][9]

Despite two architects now advising against the ringing of the bells, still nothing was done until the parish was finally forced into action following masonry falling from the tower in October 1843. Cottingham's report recommended the fitting of massive cast iron ties inside the tower to tie the walls together, something he had recently overseen in the tower at Hereford Cathedral. He also suggested demolishing the two houses that abutted the tower walls, which had become part of the very fabric of the tower, so that the fabric could be repaired properly. Finally, the eastern arch, which partially collapsed in 1818, required rebuilding through the use of a bridge centre. Cottingham estimated the cost of this work at £2,370.[9]

Work was slow to begin. The two houses were demolished in 1844 but work on the tower itself did not begin until September 1845, when a bridge centre was installed under the eastern arch. By April 1846, the Ipswich Journal reported that progress thus far has included the rebuilding of 25 feet of ashlar in the south-east corner, and the removal of the eastern arch now that the bridge centre was in place. Other works in progress were the fitting of the tie beams, the repair of the louvres and the carving of new corbels, as well as the removal of the cupola and the replacement of the battlements. The work took 3 years to complete, the grand reopening took place on 11 December 1848, as reported in the Ipswich Journal.[9]

Architecture

Typical of Norman buildings of the era, the tower's construction is substantial, with walls 36 feet (11 m) long on each side and 8 feet (2.4 m) thick.[10] Formed of four stages, the tower is 86 feet (26 m) high,[10][11] with two, large, unvaulted arches on the west and east faces. That on the west face is more like a porch in construction, with a gabled and recessed arch, decorated with fish scale-like carvings. To each side of the gateway are two tiers of niches, featuring billet decoration. The eastern arch is plainer, still recessed but without the gable.[4][5][6][8]

The eastern face has three, tall blank arches with large windows in all but the centre arch in the second stage, that of the northern and southern faces have only two arches, of which only one contains a window. The western face is again, more elaborate, with two blank arches, contained within them are a pair of recessed arches, similar in design to an arcade.[4][5][6][8]

The third stage is identical on all four faces, featuring three deep recessed window openings, divided by colonettes and hood moulds with billet decoration. Below the openings are paired blank arches. The fourth stage is identical, except rather than the pairs of blank arches below the openings, there are blank roundels, and the openings are louvred in the fourth stage.[4][5][6][8]

The tower is topped by a simple stone parapet, utilitarian in design, created during the restoration of the tower in the 1840s, which hides a sound lantern. Each face of the tower has two plain buttresses, one on each side. The south-west buttress contains the stair turret, giving access to the ringing chamber, belfry and roof. The tower is constructed almost entirely using Barnack stone.[4][5][6]

Bells

The earliest record of bells in the Norman Tower was in 1553 when five 'great bells' are recorded. The founders of the 'great bells' are unknown, but it is known that the tenor was recast in 1711 by Thomas Newman of Norwich, who also augmented the bells to six with a newly cast treble in the same year.[9][11][12]

The bells were broken up and recast in 1785 by Thomas Osborn of Downham Market, who with additional metal, made them into a ring of ten. The ring of ten cast by Osborn were hung in a massive timber frame, also dating to 1785, similar in design to the surviving frame made by John Williams in 1734 for Winchester Cathedral.[9][10][11][12][13][14][15]

In addition to the ring of ten were three clock bells: an hour bell, cast in the medieval times by an unknown founder, and two quarter bells, one of which was cast by Stephen Tonne in 1580 and the other cast by another unidentified founder in 1664. These three clock bells were dismantled and stored in the north aisle of St James's Church when the tower was restored between 1843 and 1848 because the clock was adjusted to strike the quarters on the ring of ten. These three bells were later sold to raise cover a deficit in the funds of St James, their whereabouts are unknown.[9][12]

The first full peal on the bells and indeed in the tower was on 10 November 1879, with 5,040 changes of Grandsire Triples rung on the heaviest eight bells in 3h 20m, to celebrate the birthday of the Prince of Wales. The first full peal on all ten, however, would not follow until 1895, with 5,000 changes of Kent Treble Bob Royal in 3h 40m. Regular full peals began in 1902, following the rehanging of the lightest four bells and tenor, with several per year thereafter, except the years in the First and Second World Wars. By the late 1960s, the bells were becoming increasingly difficult to ring, with worn and dated fittings and hung in a frame that did not possess the rigidity of modern, metal frames.[9][10][11][12][13][14][16]

As a consequence, fundraising began to completely restore the bells, with a goal of making them easier and more musical to ring. In 1977, the bells were removed and sent to John Taylor & Co of Loughborough for restoration. Whilst at the foundry, they were all retuned, had their canons removed and had all new fittings manufactured, with the exception of the wheels, which were only refurbished. A new cast iron and steel frame was manufactured, also by Taylor's, and installed some 12 feet (3.7 m) lower than Osborn's 1785 frame, which was left in-situ. The bells, post retuning, were rehung in the new frame, except for the hour bell, dating from 1680 by John Darbie, which was left in the old frame. Following retuning and removal of canons, the tenor bell weighs 27 long cwt 2 qrs 5 lbs (3,085 lb or 1,399 kg), striking the note C#.[2][11][13][14]

The passing of Neil Collings, Dean of St Edmundsbury from 2006 to 2009, on 26 June 2010, whose wish it was to see the ring of ten augmented to twelve, gave the cathedral and ringers ambition to finish his vision. Subsequently, a 'Norman Tower' appeal was launched later that year to raise the £40,000 required. The project involved the casting of two additional treble bells, augmenting the ring to twelve, and a thirteenth bell (a semitone) to allow a lighter ring of eight to be rung for the less experienced, rather than using the heaviest eight bells in the tower.[17][18]

John Taylor & Co, given their work in 1977 at the Norman Tower, were invited to cast the bells, supply the fittings and extend the 1977 frame to allow three additional bells. The two new trebles, which were cast in September 2011 at Taylor's foundry in Loughborough, were delivered to the Norman Tower in December, the dedication service in the cathedral followed on Easter Sunday 2012. The two new bells were named the Vestey bell and Stannard bell, after the families that donated them. The augmentation gave West Suffolk its first ring of twelve; the only other rings of twelve in Suffolk were at Grundisburgh and St Mary-le-Tower, Ipswich.[13][14][17][18][19][20]

The thirteenth bell was cast in 2013, also by Taylor's, and was a 'flat sixth' (B natural), a bell sitting between the sixth (B#) and seventh (A#) bells in the ring, to give a ring of eight using the ninth as the tenor, substituting the normal sixth for the new flat sixth. This gives a ring of eight with a tenor of 11 long cwt 1 qrs 27 lbs (1,287 lb or 584 kg) which is more suitable for teaching than using the heaviest eight, which would have a tenor of some 27 long cwt (see above).[14][18][21]

In 2018, the ringers began fundraising for the replacement of the wheels, which were last replaced in the 1902 rehanging and only refurbished in 1977. The cost is approximately £14,000 to supply the heaviest ten bells with new wheels. The bells are considered the finest example of Osborn's work in the country.[11][22]

Gallery

Western portal in 1900

Western portal in 1900 St Edmundsbury Cathedral in 1997, showing new chancel but unfinished central tower; Norman Tower to the left

St Edmundsbury Cathedral in 1997, showing new chancel but unfinished central tower; Norman Tower to the left The same view in 2019, showing the completed Millennium Tower (2005)

The same view in 2019, showing the completed Millennium Tower (2005) Western face

Western face

Similar towers

Though not as common as in Continental Europe, some churches and cathedrals in the United Kingdom still have detached bell towers, but few have rings on the size or scale of Bury St Edmunds. These include Evesham Bell Tower, the only surviving part of Evesham Abbey which now provides ringing for the local parish church; Inveraray Bell Tower, the detached tower of All Saints Church; and the detached bell towers of Chester Cathedral and Chichester Cathedral.[10][23]

Evesham Bell Tower, relic of Evesham Abbey

Evesham Bell Tower, relic of Evesham Abbey.jpg.webp) Inveraray Bell Tower

Inveraray Bell Tower.jpg.webp) Chichester Cathedral detached bell tower

Chichester Cathedral detached bell tower Chester Cathedral detached bell tower, known as the "Addleshaw Tower"

Chester Cathedral detached bell tower, known as the "Addleshaw Tower"

References

- ↑ Ross, David. "Bury St Edmunds Photo, Norman Tower (St James Gate)". Britain Express. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- 1 2 3 "The Norman Tower". Visit Bury St Edmunds. 1 April 2022. Retrieved 1 April 2022.

- 1 2 Retrieved using Google Maps 'measure distance' tool.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Historic England. "Norman Tower, Bury St. Edmunds - 1375555". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 1 April 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Pevsner, Nikolaus (2002). Suffolk. Enid Radcliffe. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 138. ISBN 0-300-09648-8. OCLC 49298277.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Baxter, Ron (25 August 2005). "Norman Gate, Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk". Corpus of Romanesque Sculpture in Britain and Ireland. Retrieved 1 April 2022.

- 1 2 "Bury St Edmunds Abbey". Suffolk Churches. Retrieved 1 April 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 West Suffolk Council, St Edmundsbury Cathedral (June 2018). Heritage Assessment (pdf) (Report). Abbey of St Edmund Heritage Partnership. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Eisel, John (21 December 2012). "The Norman Tower at Bury St Edmunds" (PDF). The Ringing World. pp. 1320–1325. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Morris, Ernest (26 February 1943). "Detached Towers of England" (PDF). The Ringing World. No. 1666. p. 98. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Pipe, George. W. (6 November 1970). "St. James' Cathedral, Bury St. Edmunds, Suffolk" (PDF). The Ringing World. No. 3106. p. 870. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 Raven, John James (1890). Church Bells of Suffolk. London, United Kingdom: Jarrold & Sons. p. 173.

- 1 2 3 4 "Bells". St Edmundsbury Cathedral. Archived from the original on 3 March 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hedgecock, James (14 June 2015). "Tower Details - Cathedral Church of St James and St Edmund, Bury St Edmunds". Dove's Guide for Church Bell Ringers. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ↑ Pease, Jack (21 November 2021). "Tower Details - Cathedral Church of the Holy Trinity, Winchester". Dove's Guide for Church Bell Ringers. Retrieved 1 April 2022.

- ↑ Felstead Database. "valid peals for Bury St Edmunds, S James, Suffolk, England". Central Council of Church Bell Ringers. Retrieved 1 April 2022.

- 1 2 "Two new Trebles for Bury St Edmunds". Suffolk Guild of Ringers. June 2012. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- 1 2 3 Shorman, Tim (4 February 2011). "Augmentation of The Norman Tower, St Edmundsbury Cathedral, Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk" (PDF). The Ringing World. pp. 101–103. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ↑ Shedden, Mandy (7 October 2011). "Two new trebles for Bury St Edmunds" (PDF). The Ringing World. pp. 1009–1010. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ↑ Shedden, Mandy (April 2012). "Dedication of the Two New Norman Tower Bells". Suffolk Guild of Ringers. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ↑ "Ringing the changes at Bury St Edmunds Cathedral". ITV News. 17 May 2013. Retrieved 1 April 2022.

- ↑ Annual Report 2018 (PDF) (Report). St Edmundsbury Cathedral. January 2019. Retrieved 1 April 2022.

- ↑ "Inveraray Bell Tower". www.inveraraybelltower.co.uk. Retrieved 1 April 2022.