| Rising From the Fiery Hell of Social Injustice, The Wings of Freedom Will Never Be Stilled | |

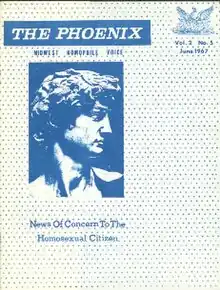

June 1967 cover of magazine | |

| Type | Magazine |

|---|---|

| Founder(s) | Drew Shafer |

| Publisher | The Phoenix Society For Individual Freedom |

| Editor-in-chief | Lance Carter |

| Editor | Dean Triton |

| Associate editor | Eric Damon |

| Staff writers |

|

| Current events |

|

| Launched | 1966 |

| Ceased publication | 1972 |

| City | Kansas City, Missouri |

| Country | US |

| OCLC number | 15000286 |

The Phoenix: Midwest Homophile Voice was an American homophile magazine that ran from 1966 to 1972.[1] It was published by The Phoenix Society for Individual Freedom, in Kansas City, Missouri, and was the first LGBT magazine in the Midwest.[2] The magazine was founded by Drew Shafer, a gay rights activist from Kansas City (KC), who was known for bringing the homophile movement to KC.[3] The magazine's motto was: “Rising From the Fiery Hell of Social Injustice, The Wings of Freedom Will Never Be Stilled.”[4]

History and background

The first issue in 1966 was originally titled The Phoenix: Homophile Voice of Kansas City, but was changed in the next issue to Midwest Homophile Voice. They were distributed at gay and straight clubs, LGBT meetings, social gatherings, college campuses, and other businesses sympathetic to the movement.[3][4] The magazine even made its way to Iowa and Nebraska.[2]

The magazine had the typical fare for a homophile magazine: poetry, artwork, cartoons, short stories, and it also delved into serious issues like the psychological aspects of homosexuality, and gave counsel about legal rights for LGBT citizens, in case of an interaction with law enforcement, or medical professionals.[3][5] The magazine was financially supported by advertising revenue from local gay establishments, mostly gay bars in the area.[6][7]

Shafer's parents were very supportive of their son and his LGBT activism. Shafer's father was a commercial printer, and he was instrumental in obtaining printing equipment for the periodical, installing an old linotype machine in the basement of the Phoenix House. The magazine was created using paste-up boards, and hand drawn graphics.[7] His mother, Phyllis Shafer, was a LGBT activist herself, and wrote under the pseudonym 'Estelle Graham' for the magazine.[8] In the July 1966 issue, she penned an essay titled "A Mother's Viewpoint On Homosexuality".[1][2]

After their successful start in publishing their own magazine, Shafer consented to be a publishing clearinghouse for the North American Conference of Homophile Organizations, in August 1966. They reprinted magazines, newsletters, and pamphlets from other homophile organizations from around the United States, including: Tangents, Vector and the Homophile Action League newsletter. They also put together North American Conference of Homophile Organization periodicals, and circulated them across the US.[3] According to Stuart Hinds, co-founder of the Gay and Lesbian Archive of Mid-America, "Kansas City became the information distribution center for the homophile movement".[2][9]

By 1972, Shafer had accumulated an enormous amount of debt ($50,000), trying to keep his publishing business going, and keeping the Phoenix House open. Advertising revenue from the magazine had dramatically dwindled as well, so the magazine ceased publication, and the house was forced to close.[2]

Legacy

In 2016, a historical marker was installed by the Gay and Lesbian Archive of Mid-America, at Barney Allis Plaza in downtown Kansas City, commemorating Shafer's magazine The Phoenix: Midwest Homophile Voice, and his work with The Phoenix Society.[5][10]

In 2021, a traveling exhibit featuring some of Shafer's magazines, and his publishing network, along with his work with the Phoenix House, was on display at the Missouri State Museum inside the state capitol. It was put together by students at the University of Missouri-Kansas City, and was focused on local Kansas City LGBT history.[3][2] However, after four days it was removed from the capitol building, after complaints it was "pushing the LGBT agenda" in the state capitol. The complaints reportedly came from Republican legislators and their staff.[11][12][lower-alpha 1]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Two photographs of the display that was removed. In the photograph from the New York Times, on the left side, you can see the magazine's motto on a display; in the photograph from Washington University in St. Louis, on the right side, you can see the display about the Phoenix Society's publishing network.[13][14]

References

- 1 2 Baim, Tracy (2012). Gay Press, Gay Power: The Growth of LGBT Community Newspapers in America (1st. ed.). Chicago: Prairie Avenue Productions and Windy City Media Group. p. 91. ISBN 978-1-4800-8052-2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Martin, Mackenzie (June 1, 2022). "Before Stonewall, this Kansas City activist helped unite the national gay rights movement". KCUR - NPR.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Cantwell, Christopher D.; Hinds, Stuart; Carpenter, Kathyrn B. (August 2017). "The Phoenix Society in Kansas City, Midwest Homophile Voice". University of Missouri–Kansas City. Making History.

- 1 2 Hearn, Brian (September 8, 2017). "Kansas City and the Rise of Gay Rights". KC Studio. Archived from the original on December 1, 2022.

- 1 2 Plake, Sarah (June 16, 2021). "Pride Month History: Kansas City had foundational role in LGBT movement nationwide". KSHB. E. W. Scripps Company. Archived from the original on June 7, 2023.

- ↑ Shafer, Drew (February–March 1969). "Advertisement for The Gaslight Lounge". The Phoenix: Midwest Homophile Voice. JSTOR: 2.

- 1 2 Jackson, David (October 5, 2016). "KC's Leading LGBT Pioneer". The Kansas City Star. p. 8.

- ↑ Jackson, David W. (2011). Changing Times: Almanac and Digest of Kansas City's Gay and Lesbian history. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-9704308-4-7.

- ↑ Metcalf, Meg (January 8, 2018). "Research Guides: LGBTQIA+ Studies: A Resource Guide: Before Stonewall: The Homophile Movement". Library of Congress.

Phoenix Society for Individual Freedom (Kansas City MO) published The Phoenix: Midwest Homophile Voice and served as a publishing house for NACHO.

- ↑ Voigt, Jason (May 27, 2022). "Phoenix Society for Individual Freedom". Historical Marker Database.

- ↑ Edwards, Jonathan (September 3, 2021). "An LGBT history exhibit went up in the Missouri Capitol. A lawmaker's staffer complained, and it disappeared". Washington Post. Archived from the original on January 31, 2023.

- ↑ Lukpat, Alyssa (September 4, 2021). "Missouri Relocates Gay History Exhibit From State Capitol". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 8, 2023.

- ↑ "Missouri Relocates Gay History Exhibit From State Capitol". The New York Times. September 4, 2021.

- ↑ "LGBTQ History Gateway To Pride". Washington University in St. Louis. 2021. Archived from the original on March 1, 2023.

Further reading

- Gunnison, Foster (1967). An Introduction to the Homophile Movement. Institute of Social Ethics.

- Pettis, Ruth M. (2015). "Homophile Movement, U. S." (PDF). glbtq Encyclopedia Project. pp. 1–6.

- Scharlau, Kevin (July 2015). "Navigating Change in the Homophile Heartland: Kansas City's Phoenix Society and the Early Gay Rights Movement, 1966–1971". Missouri Historical Review. State Historical Society of Missouri. 109 (4): 234–253. ISSN 0026-6582. OCLC 1758409.

External links

- Magazines from 1967 to 1969 at Houston LGBT History

- Six issues of magazine at JSTOR

- Memorial website for Drew Shafer