| The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex | |

|---|---|

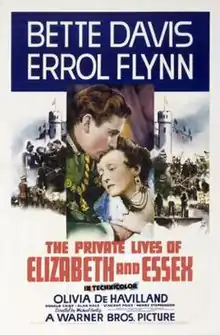

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Michael Curtiz |

| Screenplay by | |

| Based on | Elizabeth the Queen 1930 play by Maxwell Anderson |

| Produced by | Hal B. Wallis |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Sol Polito |

| Edited by | Owen Marks |

| Music by | Erich Wolfgang Korngold |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 106 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $1.07 million[1][2] |

| Box office | $1.61 million[1] |

The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex, for a time also entitled Elizabeth the Queen, is a 1939 American historical romantic drama film directed by Michael Curtiz and starring Bette Davis, Errol Flynn, and Olivia de Havilland.[3][4] Based on the play Elizabeth the Queen by Maxwell Anderson—which had a successful run on Broadway with Lynn Fontanne and Alfred Lunt in the lead roles—the film fictionalizes the historical relationship between Queen Elizabeth I and Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex. The screenplay was written by Norman Reilly Raine and Aeneas MacKenzie.

It was the fifth of nine films that Flynn and de Havilland starred in, while it was the second of his three with Davis.[5]

The supporting cast included Donald Crisp, Henry Daniell, Henry Stephenson, and Vincent Price. The score was composed by Erich Wolfgang Korngold, who later used a theme from the film in his Symphony in F sharp major. The Technicolor cinematography was by Sol Polito, and the elaborate costumes were designed by Orry-Kelly.

The film was a Warner Bros. Pictures production, and became the hit the studio had anticipated and returned a handsome profit. Among the film's five Academy Award nominations[6] was a nomination for Best Color Cinematography. Bette Davis was tipped to receive an Academy Award nomination for her role; however, she was nominated for Dark Victory (also from Warner) instead.

Plot

The Earl of Essex returns in triumph to London after having dealt the Spanish a crushing naval defeat at Cadiz. In London, an aging Queen Elizabeth awaits him with love, but also with fear, because of his popularity with the commoners and his consuming ambition. His envious rivals include Sir Robert Cecil, Lord Burghley, and Sir Walter Raleigh. His only friend at court is Francis Bacon.

Instead of the praise he expects, Essex is stunned when Elizabeth criticizes him for his failure to capture the Spanish treasure fleet as he had promised. When his co-commanders are rewarded, Essex protests, precipitating a break between the lovers. He leaves for his estates.

Elizabeth pines for him but refuses to degrade herself by recalling him. But when Hugh O'Neill, 2nd Earl of Tyrone revolts and routs the English forces in Ireland, the Queen has the excuse she needs to summon Essex. She intends to make him Master of the Ordnance, a safe position at court. However, his enemies goad him into taking command of the army to be sent to quash the rebellion.

Essex pursues Tyrone, though his letters to Elizabeth begging for much-needed men and supplies go unanswered. Unbeknownst to him, his letters to her, and hers to him, are being intercepted by Lady Penelope Grey, a lady-in-waiting who loves him too. Finally, Elizabeth, believing herself to be scorned, sends him orders to disband his army and return to London.

Furious, Essex ignores the order, orders a night march, and thinks he has finally cornered his foe. However, at a parley, Tyrone points out the smoke rising from the English camp, signifying the destruction of the food and ammunition the English army needs. Essex accepts Tyrone's terms; he and his men disarm and sail back to England.

Thinking he has been betrayed, he leads his army in a march on London to seize the crown for himself. Elizabeth offers no resistance to his forces, but once alone with him, convinces him that she will accept the kingdom's joint rule. He then naively disbands his army, and he is quickly arrested and condemned to death.

The day of his execution, Elizabeth can wait no longer. She summons him, hoping he will abandon his ambition in return for his life (which she is eager to grant). However, Essex tells her that he will always be a danger to her and walks to the chopping block.

Cast

In credits order

- Bette Davis as Queen Elizabeth

- Errol Flynn as Earl of Essex

- Olivia de Havilland as Lady Penelope Gray

- Donald Crisp as Francis Bacon

- Alan Hale, Sr. as Earl of Tyrone (as Alan Hale)

- Vincent Price as Sir Walter Raleigh

- Henry Stephenson as Lord Burghley

- Henry Daniell as Sir Robert Cecil

- James Stephenson as Sir Thomas Egerton

- Nanette Fabray as Mistress Margaret Radcliffe (as Nanette Fabares)

- Ralph Forbes as Lord Knollys

- Robert Warwick as Lord Mountjoy

- Leo G. Carroll as Sir Edward Coke

- Guy Bellis as Lord Charles Howard (uncredited)

- Forrester Harvey as bit part (uncredited)

- Holmes Herbert as Majordomo (uncredited)

- I. Stanford Jolley as Spectator outside Whitehall Palace (uncredited)

Production

Sources

The film was based on the stage play by Maxwell Anderson, Elizabeth the Queen, which had premiered on Broadway in 1930 starring Lynn Fontanne and Alfred Lunt.

Film re-titling

The title of the film was originally to be the same as the play, but Flynn demanded his presence be acknowledged in the title. However, the new title, The Knight and the Lady, upset Davis, who felt it gave the male lead more importance than her and was, to her mind, essentially "a woman's story." She sent at least two telegrams in April and June 1938 to studio president Jack L. Warner demanding that the title include the character of Elizabeth by name and before the character of Essex, or she would refuse to make the film. Elizabeth and Essex, one of Davis's preferred titles, was already under copyright as the title of a book written by Lytton Strachey. In the end, the studio acquiesced and gave the film the title it bears today, mirroring the titles of earlier historical films such as The Private Life of Henry VIII and The Private Life of Don Juan.[7]

On-screen partnership of Davis and Flynn

Davis recounted later in life her difficulties in making the film. She had been very enthusiastic about the challenge of playing Elizabeth (in 1955, she would play her as an old woman in The Virgin Queen). She had lobbied for Laurence Olivier to play the part of Essex, but Warner Brothers, nervous at giving the part to an actor who was relatively unknown in the United States, instead cast Errol Flynn, who was at the height of his success. Davis felt he was not equal to the task, and also believed from past experience that his casual attitude to his work would be reflected in his performance.

For her own part, Davis studied the life of Elizabeth, worked hard to adopt a passable accent, and shaved her hairline to achieve a greater resemblance. Many years later, however, Davis viewed the film with her friend, Olivia de Havilland. At the film's end, Davis turned to de Havilland and admitted, "I was wrong, wrong, wrong. Flynn was brilliant!"

Flynn and Davis, born respectively in 1909 and 1908, were almost the same age (30 and 31 in 1939), in contrast to the age gap of more than 30 years between Elizabeth and Essex in real life. Davis was also less than half the age the real Elizabeth had been at the time of the events depicted, which was 63.

A final scene of Essex on the execution block was cut after previews.[8]

Reception

Box office

The film made a profit of $550,000.

According to Warner Bros figures the film earned $955,000 domestically and $658,000 foreign.[1]

Critical

The public liked Flynn's charming rogue of a character, his undisguised Tasmanian accent notwithstanding, but the critics found him to be the weak link in the production, with The New York Times writing, "Bette Davis's Elizabeth is a strong, resolute, glamour-skimping characterisation against which Mr. Flynn's Essex has about as much chance as a beanshooter against a tank."[9]

Footage from the movie was re-used in The Adventures of Don Juan (1948).[8]

In the years between Flynn's death and the release of the film on videocassette and its first showings on cable television, the title was changed to Elizabeth the Queen. The current title was restored some years later.[10]

Awards

The film was nominated for five Academy Awards:[11]

- Best Art Direction (Anton Grot)

- Best Cinematography (Color) (Sol Polito, W. Howard Greene)

- Music (Scoring) (Erich Wolfgang Korngold)

- Sound Recording (Nathan Levinson)

- Special Effects (Byron Haskin, Nathan Levinson)

The film is recognized by American Film Institute in these lists:

- 2002: AFI's 100 Years...100 Passions – Nominated[12]

- 2005: AFI's 100 Years of Film Scores – Nominated[13]

References

- 1 2 3 Warner Bros financial information in The William Shaefer Ledger. See Appendix 1, Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, (1995) 15:sup1, 1-31 p 20 DOI: 10.1080/01439689508604551

- ↑ Glancy, H. Mark. "MGM Film Grosses, 1924-1948: The Eddie Mannix Ledger", Historical Journal of Film, Radio, and Television, 12, no. 2 (1992), pp. 127-43.

- ↑ Variety film review; October 4, 1939, page 12.

- ↑ Harrison's Reports film review; October 14, 1939, page 162.

- ↑ Vagg, Stephen (November 10, 2019). "The Films of Errol Flynn: Part 2 The Golden Years". Filmink.

- ↑ "NY Times: The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex". Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. 2009. Archived from the original on 2009-12-30. Retrieved 2008-12-12.

- ↑ Rosenkrantz, Linda (2003). Telegram! Modern History As Told Through More Than 400 Witty, Poignant & Revealing Telegrams (First ed.). New York, NY: Henry Holt and Company. p. 74. ISBN 0-8050-7101-6.

- 1 2 Tony Thomas, Rudy Behlmer * Clifford McCarty, The Films of Errol Flynn, Citadel Press, 1969 p 86

- ↑ Adrienne L. McLean, Glamour in a Golden Age: Movie Stars of the Nineteen Hundred and Thirties, Rutgers University Press, 2011, p. 97.

- ↑ "The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex - Trivia". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ↑ "The 12th Academy Awards (1940) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Retrieved 2011-08-12.

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Passions Nominees" (PDF). Retrieved 2016-08-19.

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Years of Film Scores Nominees" (PDF). Retrieved 2016-08-19.

External links

- Elizabeth the Queen at the Internet Broadway Database

- The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex at IMDb

- The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex at the TCM Movie Database

- The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex at AllMovie

- The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex at the American Film Institute Catalog

- 1952 Best Plays radio adaptation of original play Elizabeth the Queen at Internet Archive

- 1945 Theatre Guild on the Air radio adaptation of original play Elizabeth the Queen at Internet Archive