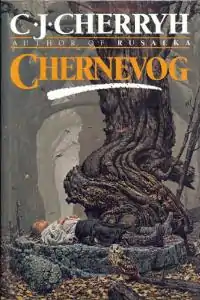

Chernevog, the second book in the "Russian" series | |

Rusalka Chernevog Yvgenie | |

| Author | C. J. Cherryh |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | Keith Parkinson (original cover artwork) |

| Country | United States |

| Genre | Fantasy |

| Publisher | Del Rey Books |

| Published | 1989–1991 |

| Media type | Print (hardcover, paperback and ebook) |

The Russian Stories, also known as the Russian Series, the Russian Trilogy and the Rusalka Trilogy, are a series of fantasy novels by science fiction and fantasy author C. J. Cherryh. The stories are set in medieval Russia along the Dnieper river,[1] in a fictional alternate history of Kievan Rus', a predecessor state of modern-day Russia, Belarus and Ukraine. The three books in the series are Rusalka (1989), Chernevog (1990), and Yvgenie (1991). Rusalka was nominated for a Locus Award in 1990.[2]

The stories draw heavily from Slavic mythology and concerns the fate of a girl who has drowned and become a rusalka.[3] For example, a "Rusalka" is a type of life-draining Slavic fairy that haunts a river or lake. And "Chernevog" is an alternate spelling of Chernobog, a mysterious Slavic deity. Other creatures in the books derived from Slavic folklore include Bannik, Leshy and a Vodyanoy.[4]

How magic operates in these books sets them apart from other Cherryh works of fantasy. Wizards are presented as especially dangerous in these novels because even their most casual desires, if expressed, may set into action a course of events with unpredictable outcomes. Wizards in the series therefore must carefully attend to what they think lest they accidentally set loose magical forces that could result in negative outcomes.

The books can therefore be read as a cautionary tale regarding the incompatibility of magic and human society, and also as a criticism of the cavalier treatment of magical power in many works of fantasy, especially high fantasy.[5] They are best described as historical fantasy, although they also borrow elements from the horror fiction genre.

Magic in the series

In an essay entitled "Shifting Ground: Subjectivities in Cherryh's Slavic Fantasy Trilogy", academic Janice M. Bogstad says the Russian Series describe three levels of magic:

- Folkloric magic performed by local creatures, including bannicks, leshys[lower-alpha 1] and vodyanois, which is often misinterpreted as peasant superstition;[7][5]

- Wish magic performed by wizards, an imprecise art because of the way wishes interact with other wizards' wishes;[8][5]

- Power magic, the "most destruction of magics" that draws its power from "dark forces" in a "parallel realm", practised by some wizards, but considered sorcery by others.[9][10]

Franco-Bulgarian philosopher Tzvetan Todorov called this second level of magic "pan-determinism" where "the limit between the physical and the mental, between matter and spirit, between word and thing, ceases to be imperious".[11]

Bogstad says that besides the books being a story about a girl-turned-rusalka, it is about "humaniz[ing] the experience of magic".[12] Each characters' experience with magic is subjective as they never get to see the complete picture, and can only speculate as to what they think the "presence of magic" is causing.[7] Bogstad calls the story "a kind of science of magics" because of the way in which the characters explore of this phenomenon.[7]

Reception

Academic Janice M. Bogstad described this series as an "unusual fantasy trilogy" that "deserves attention" because Cherryh has departed from traditional fantasy based on Celtic folklore and introduced Western readers to the lesser known Slavic mythology.[3] Science fiction and fantasy writer Roland J. Green described Cherryh's Russian series as her "most significant work of fantasy".[13] Latin language literature scholar, Mildred Leake Day called the Russian Stories "the very best of the books of sorcery".[1]

Publication information

- Cherryh, C. J. (1989). Rusalka (1st ed.). Del Rey Books.

- Cherryh, C. J. (1990). Chernevog (1st ed.). Del Rey Books.

- Cherryh, C. J. (1991). Yvgenie (1st ed.). Del Rey Books.

- Cherryh, C. J. (2010). Rusalka (e-book ed.). Spokane, Washington: Closed Circle Publications.

- Cherryh, C. J.; Fancher, Jane (2012). Chernevog (e-book ed.). Spokane, Washington: Closed Circle Publications.

- Cherryh, C. J. (2012). Yvgenie (e-book ed.). Spokane, Washington: Closed Circle Publications.

Cherryh self-published revised editions of Rusalka, Chernevog and Yvgenie in e-book format at Closed Circle Publications between 2010 and 2012.[14] Authorship of the e-book edition of Chernevog is credited to C. J. Cherryh and Jane Fancher because of Fancher's contributions to the revisions.[15] Cherryh said that in these e-book editions, "there's been a little change in Rusalka, a greater change in Chernevog, and a massive change in Yvgenie—in the latter, I've rewritten it line by line: nothing’s left untouched."[16]

Explanatory notes

Citations

- 1 2 Day, Mildred Leake (1991). "Arthurian News and Events". Quondam et Futurus. Scriptorium Press. 1 (3): 106–107. JSTOR 27870146. (subscription required)

- ↑ "1990 Award Winners & Nominees". Worlds Without End. Retrieved July 15, 2009.

- 1 2 Bogstad 2004, p. 114.

- ↑ Bogstad 2004, p. 115.

- 1 2 3 Bogstad 2004, p. 126.

- ↑ Cherryh 2010a, p. 36.

- 1 2 3 Bogstad 2004, p. 117.

- ↑ Bogstad 2004, p. 120.

- ↑ Bogstad 2004, p. 123.

- ↑ Cherryh 2012a, pp. 98–99.

- ↑ Todorov, Tsvetan (1975). The Fantastic: A Structural Approach to a Literary Genre. Translated by Richard Howard. Cornell University Press. p. 112.

- ↑ Bogstad 2004, p. 116.

- ↑ Green, Roland J. (December 8, 1991). "Watching the past saves the future". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on October 18, 2016. Retrieved March 1, 2013 – via HighBeam.

- ↑ "Rusalka". Closed Circle Publications. Retrieved August 14, 2013.

- ↑ Cherryh, C. J. (October 19, 2012). "Editing older novels to new editions". Wave Without a Shore. Retrieved August 15, 2013.

- ↑ Cherryh, C. J. (March 31, 2012). "Getting very close to adding Chernevog and Yvgenie". Wave Without a Shore. Retrieved August 15, 2013.

Works cited

- Bogstad, Janice M. (2004). "Shifting Ground: Subjectivities in Cherryh's Slavic Fantasy Trilogy". In Carmien, Edward (ed.). The Cherryh Odyssey. Wildside Press LLC. pp. 113–131. ISBN 978-0-8095-1071-9.

- Cherryh, C. J. (2010a) [1989]. Rusalka (e-book ed.). Spokane, Washington: Closed Circle Publications.

- Cherryh, C. J. (2012a) [1990]. Chernevog (e-book ed.). Spokane, Washington: Closed Circle Publications.

Further reading

- D'Ammassa, Don (January 2009). Encyclopedia of Fantasy and Horror Fiction. Infobase Publishing. p. 54. ISBN 978-1-4381-0909-1.

- Buker, Derek M. (January 2002). The Science Fiction and Fantasy Readers' Advisory: The Librarian's Guide to Cyborgs, Aliens, and Sorcerers. American Library Association. p. 157. ISBN 978-0-8389-0831-0.

External links

- Rusalka series series listing at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database