The Sally (1764) was an 18th century Rhode Island brigantine slave ship launched from Providence and destined for the western-most coast of Africa.[1] Like many voyages from the state at this time, the ship was charted by Nicholas Brown and Company, a merchant firm founded by the prominent Brown family (of brothers Nicholas, Joseph, John, and Moses).[2] This same company, and the successful mercantile family, was the main benefactor in the foundation of Brown University in 1764 (the same year as The Sally’s departure).[1] The story of The Sally rose to infamy upon return – and for centuries, thereafter – due to high mortality rates following a slave revolt and widespread health issues. Of the 196 captives on board, more than 109 were either murdered by captain, Esek Hopkins, and crew, died from diseases and starvation, or took their own lives.[3] Within the state of Rhode Island, The Sally serves an important historical symbol of the atrocities of northern slavery, as well as the legacy of slave labor within prominent American institutions, namely Brown University.[4]

Description

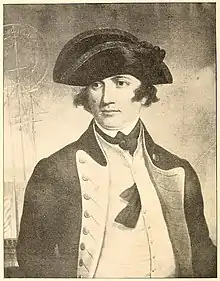

Sally was a one-hundred-ton brigantine ship, captained by Esek Hopkins and financed by the Brown brothers. Prior to departure, the ship was outfitted with tremendous cargo stores, both for sustenance and trade. Local Rhode Island merchants contributed significantly to the ship’s supplies. Hopkins kept a detailed inventory log of the contents, including but not limited 40 handguns, 40 shackles, 7 swivel guns, 30 loaves of bread, and 1,800 onions.[3] As a prime bartering tool, the ship also carried 185 barrels (equivalent to more than 17,000 gallons) of rum.[1]

Sugar – a necessary ingredient in rum – was manufactured in the Caribbean by enslaved peoples, and, subsequently, exported to the Northeastern United States.[5] This rum was distilled in and around Rhode Island, loaded onto ships like these, and used as barter for slaves once these ships made landfall in Africa. The Sally’s reliance on rum in exchange for slaves is a prime example of the Triangular Trade that dominated 18th century enslavement.[5]

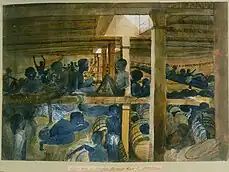

During the arduous journey of more than one year, death tolls continued to mount: "Hopkins eventually acquired a cargo of 196 Africans, but it took him more than nine months to do so, an exceptionally long time for a slave ship to remain on the African coast, especially for those confined below decks. By the time the Sally set sail for the West Indies, nineteen Africans had already died, including several children and one woman who “hanged her Self between Decks.” A twentieth captive, also a woman, was left for dead on the day the ship sailed."[6] Each death - 109 in total - was carefully accounted for in captain's log books.[1] While the remaining slaves were either auctioned in Antigua or brought back to Rhode Island, the voyage was publicly perceived as a failure, forcing the Brown brothers to extend apologies to many of their investors.[6]

History

The Brown family had cemented their position as Rhode Island aristocracy long before the foundation of their namesake university. For decades, the Brown’s had owned and operated businesses and trading vessels (under the Nicholas Brown and Company) around New England that facilitated trade between the New World and Europe. Simultaneously, The College of Rhode Island moved from Warren, Rhode Island to Providence in 1770 and was subsequently named after 1786 alumnus, Nicholas Brown, Jr., after he became the largest historical benefactor. With control over local institutions of higher education and the mercantile economy, the Brown family exercised significant control throughout the state and New England, writ large.

For this reason, the Brown family’s tie to the slave trade served as the economic backbone of Rhode Island at the time. The family sent ships on three separate voyages to Africa - “one was captured by pirates, the Sally was a financial disaster, and the third voyage was only slightly profitable.”[4] After more than a decade, Nicholas Brown opted out of the slave trade not for abolitionist rationale but for lack of profitability.[4] Despite this, the Brown family used slaves from both The Sally and its other voyage as capital in the fledgling Rhode Island economy, as well as in the foundation of Brown University’s campus in Providence. Letters between Brown brothers and Captain Hopkins suggest that the family demanded at least 4 young slaves from the voyage for personal use - individuals who would later be instrumental in the construction of buildings on the Brown University campus, such as University Hall.[4][7]

Legacy

The legacy of The Sally and its involvement in the perpetuation of northern slavery is two-fold. First, the ship offers an example of both the atrocities of the middle passage, as well as the attempts of many captured Africans to assert their personhood long before abolition. While nearly 99% of deaths that occurred during Middle Passage were attributable to disease and other causes, revolts like The Sally's did impact the magnitude of the slave trade.[8] Threat of resistance forced chartered ships to carry extra crew members and supplies, evidenced by the extensive cargo log kept by Hopkins.[7] Recent scholarship suggests that "crew numbers of slave ships were normally 50 percent higher than on produce carriers of similar size and largely accounted for the fact that about 18 percent of Middle Passage costs were attributable to potential slave revolts in transit. The latter figure suggests that, between 1680 and 1800 [...] the number of slaves shipped across the Atlantic could have been 9 percent greater than it actually was."[8] Stories like that of The Sally demonstrate the impact of small-scale defiance on slaving practices. While generally ignored by historical accounts, the revolts of these enslaved peoples, from captivity, throughout Middle Passage, and into the New World offered a symbol of fortitude among slaves long before abolitionist efforts began.

.JPG.webp)

Secondarily, The Sally exposes the deep roots of slavery and colonialism within the Northeast, specifically the state of Rhode Island. The state's most prominent institution, Brown, remains inextricably connected to the atrocities of perpetuated by this specific voyage. As recently as 2021, the university's undergraduate student body voted in favor of reparations for descendants of the enslaved people instrumental in Brown's construction. Administration has yet to offer a conclusive decision on what, if any, monetary compensation will be offered. This student outcry is not the first time Brown has been forced to reckon with violence of its past; in 2006, it became the first university to public a report that dealt with historical ties to slavery.[9] Since this publication, the university has erected memorials around campus to pay tribute to this past, as well as funded the Simmons Center for Slavery and Justice in 2012, named after former Brown president, Ruth J. Simmons, who became the first African-American president of an Ivy League institution in 2001.[10] In a press release, the university describes the new initiative: "Recognizing that racial slavery was central to the historical formation of the Americas and the modern world, the Simmons Center creates a space for the interdisciplinary study of the historical forms of slavery while also examining how these legacies continue to shape our contemporary world."[10]

References

- 1 2 3 4 "Account of the Slave Ship Sally | EnCompass". Retrieved 2023-05-05.

- ↑ Ballore, Jonathan, "Invoice: Ballore, Jonathan to Nicholas Brown & Co.: August 13, 1764 " (1764). Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice, Voyage of the Sally. Brown Digital Repository. Brown University Library.

- 1 2 "The Voyage of the Slave Ship Sally: 1764-1765". cds.library.brown.edu. Retrieved 2023-05-05.

- 1 2 3 4 Loury, Glenn C. (2004). "Brown University to Consider Reparations on Account of the Institution's Past Ties to Slavery". The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education (43): 18–20. doi:10.2307/4133533. ISSN 1077-3711. JSTOR 4133533.

- 1 2 "Rhode Island Connection". The Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition. 2015-04-27. Retrieved 2023-05-05.

- 1 2 Center for Slavery and Justice. (2006). Slavery and Justice: Report of the Brown University Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice. Slavery and Justice. Retrieved May 6, 2023, from https://slaveryandjustice.brown.edu/sites/default/files/reports/SlaveryAndJustice2006.pdf

- 1 2 "Brown Digital Repository | Item | bdr:303394". repository.library.brown.edu. Retrieved 2023-05-05.

- 1 2 Richardson, David (2001). "Shipboard Revolts, African Authority, and the Atlantic Slave Trade". The William and Mary Quarterly. 58 (1): 69–92. doi:10.2307/2674419. ISSN 0043-5597. JSTOR 2674419.

- ↑ "'It's Brown's responsibility': Here's what undergraduates want reparations to look like". NBC News. 2 April 2021. Retrieved 2023-05-05.

- 1 2 "Simmons Center | Brown University". simmonscenter.brown.edu. Retrieved 2023-05-06.