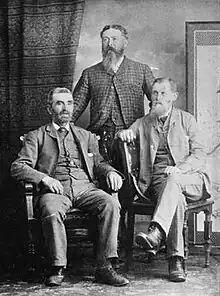

The Three Greenhorns were three Englishmen, Samuel Brighouse, William Hailstone and John Morton, who were the first white settlers in the area known today as Vancouver's West End. They earned the nickname “Three Greenhorn Englishmen" because they bought land for what was believed to be an inflated price.

Early lives

Born in 1835, John Morton was from a family of eight brothers and sisters in Salendine Nook, Huddersfield, England. They lived near a public house by the name of The Spotted Cow, which was owned by Samuel Brighouse who had a son, also Samuel, born in 1836. The Mortons were pot-makers, having originally moved from Scotland in the 1580s to escape from religious persecution. They settled in Salendine Nook because of a particular type of clay which was good for making pots.[1] John and Samuel were cousins. In 1862, they decided to sail for Canada to join in the Cariboo Gold Rush and met William Hailstone on the voyage.[2] In June of that year, they arrived at the place that today is Vancouver.[3][4]

Cariboo Goldfields

With Brighouse and Hailstone, Morton tried prospecting in the Cariboo gold fields. They made two trips, walking a distance of some 1,400 miles. Although unsuccessful in their main endeavour, Morton chanced upon a profitable side-line in selling horseshoe nails. A blacksmith in the outlying territory had run out of nails, and Morton saved the day by producing twenty-two nails from his outfit and making the sum of twenty-two dollars in the process. The three friends returned to the small settlement of New Westminster to ponder their next move.[1]

The Brickmaker's Claim

One day, Morton was passing by a shop window in the settlement when he saw a lump of coal for sale in the window. In a later newspaper report it was recorded that "his interest was specially excited". Coal was a rare commodity in those parts, the only available fuel being wood. But most of all, the sight had triggered his interest as a potter: he knew that a certain kind of clay used in pot-making was usually found near coal deposits. He entered the shop and on asking the shopkeeper where the coal had come from was pointed in the direction of a native who was disappearing down the road. Morton hurried after the Indian, caught up with him and made arrangements to visit the coal seam. Taking a guide, he first visited False Creek and then Coal Harbour.[3] He found little of value in the soil: most of the coal seam and clay deposit had been washed away.[1]

But the situation of the land at Burrard Inlet, overlooking a natural deep water harbour, so impressed Morton and his friends that they set about making enquiries about purchasing it. They discovered that it had neither been staked nor surveyed, and so they acquired 180 acres each, the maximum stake permissible under the law of the time, bought for $550.75. The lot contained what later became the West End district of Vancouver.[5] By Christmas 1862, they had cleared a small part of the land and created a log cabin, much to the derision of the local inhabitants who christened them "The Three Greenhorns". It was even suggested that the colonial government had deliberately placed a shiny piece of coal in the shop window with the intention of enticing someone like Morton to buy the land.[6] Although their investment in this remote piece of forest was considered a futile one, there was another person who was interested in the land. Robert Burnaby made a claim that he had obtained the original preemption for the property, but his claim was dismissed by the court.[3] Judge Chartres Brew condemned the documents Burnaby produced as forgeries, saying that they were "obviously written by a liar or a knave."[7]

The cabin was situated on a bluff above the sea. The greenhorns turned their hand to raising cattle and becoming brick makers. Only one of them remained in the cabin a month at a time, while the others went to work in New Westminster. But the brickmaking business failed - in a country where wood was in plentiful supply, bricks were not in great demand at that time, the clay was of poor quality and New Westminster was too far away to transport large quantities of bricks to. There was the solitude, too, which on one occasion made John Morton feel very exposed. He was woken at night by noises outside the cabin. Getting dressed, he went to take a look and saw a gathering of Indians chanting and the body of a woman hanging from a tree. Next day he reported the matter to the police in New Westminster and an investigation revealed that the dead woman had killed a baby and been hanged for murder.[3][4]

Deadman's Island

A government surveyor who was surveying the boundaries of the Bricklayer's Claim, offered a small island in the bay known as Deadman's Island (also shown on some maps as Coal Island) to Brighouse for $5, but Brighouse declined in the belief that they already had plenty of land.[3] In 1865, Morton rowed across to the island and was fascinated to find hundreds of red cedar boxes perched in the upper branches of the trees. But going to touch one of the boxes, he found it fragile and it crumbled easily, showering him with the bones of a long-deceased Indian. The boxes contained the bones of Squamish people and when Morton made enquries with the chief of the tribe, he was told that the island had been the site of a massacre in which some 200 tribesmen had been killed. Morton quickly changed his mind about buying the island.[8]

New Liverpool

The land originally known as the Brickmaker's Claim was later renamed "New Liverpool" by investors keen to develop the area. The Greenhorns tried to sell the land as lots, claiming New Liverpool would soon be a major city, but initially they had had no success.[5]

In 1886, they were persuaded to donate one third of the property to the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) as an incentive for them to build a railway through to Coal Harbour, hoping that this might bring people to the area to buy the lots. By the time CPR had made it to Gastown, however, the "Three Greenhorns" had parted ways, feeling that they had been cheated. Morton went to California in search of gold, and Brighouse went to farm in Richmond. Hailstone had sold his interest to Brighouse for a $20 gold piece, several sacks of flour worth $5 and an Indian pony with a string halter worth $25, and returned to England.[5][6]

Entrepreneur John McDougall was contracted to clear a large part of the Three Greenhorns' "Liverpool Estate." He was known as "Chinese McDougall" because the Chinese labourers he used to do this. But in February 1887 the Chinese workers were attacked by an angry mob who burned their homes and forced them to leave town.[3]

In 1887, the lots began to sell, with prices from $350 to $1,000, as people realised the potential of the area. With CPR building rail lines, a hotel was going up, roads were being laid through the area plus the establishment of Stanley Park, lots began to move quickly. By 1888, the area was gaining respectability and had swiftly become an attractive investment to wealthy and elite buyers with fine views across Burrard Inlet and a reasonable distance from the smelly warehouses of Gastown.

The West End

.jpg.webp)

The West End grew up on the Brickmaker's Claim as "high class" residential housing, although this declined with the development of Shaugnessy by the CPR in 1911. Today, Vancouver's art-deco Marine Building marks the site of the Greenhorns’ log cabin.[9] At 22 stories and a height of 341 feet, the building overlooks the terminus of the Canadian Pacific Railway. The West End of Vancouver neighbours Stanley Park and the areas of Yaletown, Coal Harbour and the downtown financial and central business districts.[10]

Later lives

In 1864 Brighouse purchased almost 700 acres of land in the area that would become the town of Richmond and became a man of considerable wealth. After farming in the district, he returned to Vancouver in 1881. He became an alderman in 1887, having been involved in obtaining the City Charter. In 1911 he returned to England and died there two years later.[3][11]

On his return to England, Hailstone married and had two daughters. He then returned to the Vancouver area and remitted his earnings home, but his wife died and left everything to their daughters. He returned to Yorkshire and, according to rumour, he died after falling down stairs and breaking his neck.[12]

Morton's first wife was Jane Ann Bailey of Blackpool, England, but she died in childbirth in 1881. At this time, Morton was subsisting on doing odd jobs such as ditch digger and milk roundsman. He placed his daughter in a Roman Catholic convent in New Westminster and his son with a private family. However, Jane had owned a tea merchant's business in Blackpool, England, with her brother James. Morton was able to claim her entire share of the business, worth about 700 pounds, and use the money to retain his part in the Brickmaker's Claim and, in 1884, to purchase a large farm at a place called Mission. He married Ruth Mount, set up a brickmaking business in Clayburn, part of the town of Abbotsford, and ran the farm at Mission. It was from here, on 13 June 1886, that his family saw the Great Vancouver Fire burning in the distance.

Ruth Morton described life in Vancouver with her husband: “Mr. Morton and I came over from New Westminster one summer’s day in 1884 for an outing, just my late husband and myself. We had to buy our tickets for the stage the previous day, and afterwards we drove over the old Hastings Road, then a corduroy road through the trees. Mr. Morton was anxious that I should see the white sand at English Bay, and we tried to hire a boat by which we could go out of the First Narrows, but no seaworthy boat could be procured—they were all leaky—so we did not go. He was very fascinated with the beauty of Vancouver as it was then. Whilst Mr. Edmund Ogle, my nephew, and I were waiting on the beach for Mr. Morton at Gastown, in front of us was a sow digging up the clams, and a crow hopping in front of her getting a meal from the bits of the clams. Edmund Ogle started a dry goods business in Vancouver, on Carrall and Powell streets I think, a week before the fire; all was destroyed; he lives in Toronto now. We saw the English church [St. James] and at George Black’s [Hastings] had lunch, and then went back to New Westminster on the stage, and from there up to Mission to the farm. At the time of the fire we were living at Mission. That Sunday afternoon a cloud of black smoke hovered high in the air across the river; it was evident a big fire was burning somewhere."[3][13]

When Morton died in 1912, he left an estate valued at approximately $769,000. His will was dated 22 May 1911 and witnessed by a nephew of Ruth Morton and a Baptist preacher. The will left $100,000 to the Baptist Educational Board of B.C. together with over seven acres of land in South Vancouver. Before his death he not only laid the cornerstone of the First Baptist Church at the corner of Nelson and Burrard streets but set aside the equivalent of $11,000 dollars to build the Baptist Church since known as the Ruth Morton Memorial in South Vancouver.[13]

Memorial to the Three Greenhorns

In 1967, a memorial was installed to commemorate The Three Greenhorns. Situated on Beach Avenue and Denman Street, English Bay, the bronze sundial stands on a granite pedestal 4'5" high and is decorated with geometric patterns. Cunningham Drug Stores Ltd. presented it to the City of Vancouver. An inscription in stone reads: "This sundial commemorates three English ‘Greenhorns’ - Samuel Brighouse, John Morton and William Hailstone who, in 1862, filed the first claim and planned the first home and industry in the then heavily wooded area now bounded by Burrard Inlet, Stanley Park, English Bay and Burrard Street to which they received title in 1867." An inscription on the sundial says, "I mark my hours by shadow, mayest thou mark thine by sunshine."[14]

References

- 1 2 3 Morton, Michael Quentin (May 2006), In the Heart of the Desert (1st edition) (In the Heart of the Desert ed.), Aylesford, Kent, United Kingdom: Green Mountain Press (UK), ISBN 978-0-9552212-0-0, 095522120X

- ↑ George Redmonds (2004), NAMES AND HISTORY (NAMES AND HISTORY: PEOPLE, PLACES AND THINGS. ed.), LONDON: HAMBLEDON AND LONDON LTD, ISBN 1-85285-426-X, 185285426X

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "New Liverpool and the Greenhorns" (PDF). Vancouver Exposed - A History in Photographs. Retrieved 25 August 2011.

- 1 2 Derek Pethick (1984), Vancouver, the pioneer years, 1774-1886, Langley, B.C: Sunfire Publications, ISBN 0-919531-13-X, OL 2592423M, 091953113X

- 1 2 3 Chamdler, Maggie. "West End History". Retrieved 25 July 2011.

- 1 2 Jill Foran (2003), Vancouver's old-time scoundrels, Canmore, Alta: Altitude Pub. Canada, ISBN 1-55153-989-6, 1551539896

- ↑ Tom Snyders (2001), Namely Vancouver, Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, ISBN 1-55152-077-X, OCLC 42683110, OL 3599859M, 155152077X

- ↑ Richard M. Steele (1993), The Stanley Park explorer (Stanley Park ed.), Heritage House Publishing Co., ISBN 1-895811-00-7, OL 24831611M, 1895811007

- ↑ "The birth of a city, from humble beginnings as a two-block strip on the Gastown waterfront",Vancouver Sun, 6 April 2011,

- ↑ Vancouver History and Heritage

- ↑ "Samuel Brighouse fonds", City of Vancouver Archives, retrieved 24 July 2011

- ↑ "William Hailstone fonds", City of Vancouver Archives, retrieved 24 July 2011

- 1 2 "Major James Skitt Matthews, Early Vancouver, Vol. 2 (Vancouver: City of Vancouver, 2011), p.109-110." (PDF), City of Vancouver Archives, retrieved 30 January 2012

- ↑ "George Cunningham Memorial Sundial", Public Art Registry, City of Vancouver Community Services Group, retrieved 25 July 2011