| |

Former names | Tampa Junior College (1931–1933) |

|---|---|

| Motto | Esse quam videri |

Motto in English | To be, rather than to seem to be |

| Type | Private university |

| Established | 1931 |

| Accreditation | SACS[1] |

Academic affiliations | AAM, IC&UF, NAICU,[2] |

| Endowment | $42.5 million+ (2019)[3] |

| President | Ronald L. Vaughn |

| Students | 9,304 [4] |

| Location | , , United States |

| Campus | Urban, 110 acres (0.45 km2) |

| Colors | Black, red, and gold[5] |

| Nickname | Spartans |

Sporting affiliations | NCAA Division II – Sunshine State |

| Mascot | Spartacus |

| Website | www |

| |

The University of Tampa (UT) is a private university in Tampa, Florida. It is accredited by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools. UT offers more than 200 programs of study, including 22 master's degrees and a broad variety of majors, minors, pre-professional programs, and certificates.

Plant Hall, UT's central building, once housed the Tampa Bay Hotel, a resort built by Henry B. Plant in 1891, and the Moorish minarets atop the distinctive structure have long been seen as an iconic symbol of Tampa.[6]

History

Tampa Junior College

In 1931, Frederic H. Spaulding, the principal of Tampa's Hillsborough High School, established the private Tampa Junior College to serve as one of the first institutions of higher education in the Tampa Bay area. The college offered a limited selection of degree programs, with most classes held in the evening on the campus of Hillsborough High School.[7][8][9]

Move and name change

Two years later, the school moved to its current location on the grounds of the recently closed Tampa Bay Hotel, which Henry B. Plant had built in 1891 directly across the Hillsborough River from downtown Tampa.[10] The sprawling resort initially featured a quarter-mile long main building with over 500 guest rooms along with several adjoining buildings and amenities ranging from an indoor pool to a casino to a race track, all spread across six acres of land. After some initial success, however, it struggled to consistently attract enough patrons to make a profit, The city of Tampa purchased the hotel after Plant's death and kept it open by contracting out daily operations to private companies, but it finally shut down in 1931 due to a significant downturn in tourism with the coming of the Great Depression. In 1933, the city agreed to allow Tampa Junior College to move its operations to the former hotel grounds rather than let the iconic buildings remain empty.[8]

With the move to a much larger facility, Tampa Junior College became the University of Tampa (UT) and expanded its course offerings, and Spaulding resigned his position at Hillsborough High School to run the university full time.[8] In 1941, UT signed a 99-year lease on the former resort with the City of Tampa for $1 per year, and the main building officially was naned Plant Hall.[11] The lease included all of the Tampa Bay Hotel property except for the southeast wing Plant Hall, which became the location of the Henry B. Plant Museum.

Slow growth

The university grew slowly over the next few decades, becoming a well-respected institution of learning that predominantly served students from the greater Tampa Bay area. In 1951, the university received full accreditation by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools (SACS).[12] While The University of Tampa succeeded academically, it faced intermittent financial difficulties for much of its history. These problems first surfaced in the mid-1930s, when the deepening Great Depression decreased enrollment and strained the new school's ability to educate students while maintaining its large campus and gradually converting Plant Hall's former hotel rooms into classrooms and offices.[13] Another crisis several decades later forced a 1974 decision to fold the successful University of Tampa Spartans football program because the school could no longer afford the cost of competing in NCAA Division I-A football.[14][13]

In 1986, local businessman Bruce Samson dropped out of Tampa's mayoral campaign to become UT's president, a position he was offered due in part to his background in banking and finance.[15] Samson successfully eliminated the school's $1.4 million annual budget deficit through "hardnosed" decisions, including withdrawing from all NCAA Division I sports. However, after he left in 1991 to return to private business, the school again fell into financial difficulties. Declining enrollment led to the return of serious budget deficits, leading to serious cuts to faculty positions and academic programs. UT faced an uncertain future, and some local leaders suggested that the cross-town public University of South Florida should take over operations of the long-time private school.[13]

Modern expansions

In 1995, the Board of Trustees elected Ronald L. Vaughn, then dean of UT's College of Business, as the school's new president. His initial efforts were aimed at bringing the campus up-to-date with new dorms and a major renovation to the business school. Vaughn also launched the "Take UT to the Top" campaign with the goal of raising $70 million in 10 years and restoring the University's endowment. The campaign raised $83 million, and later observers credit this successful fund drive with saving and modernizing the university.[13] Two important contributions came from the John H. Sykes family of Tampa - a gift of $10 million in 1997 and another donation of $28 million in 2000, which was thought to be the largest such gift to a Florida university at the time.[16][13]

The additional funds were used to purchase adjacent land and continue to add modern facilities; over $575 million in construction has been completed on campus since 1998.[17] The university has also hired additional faculty, permitting the school to expand its student population while maintaining a 17:1 student-faculty ratio.[18] For his efforts in rescuing the university and increasing enrollment, Vaughn has a salary that is in the top 10 of mid-sized, private institutions.

Academics

UT offers 200 areas of study for undergraduate and graduate students. Classes maintain a 17:1 student-faculty ratio.[19] UT employs no teaching assistants.

Some of UT's most popular majors include international business, biology, marketing, marine science, criminology, finance, communication, psychology, sport management, entrepreneurship and nursing. UT recently launched a new major in cybersecurity.[20]

The university is organized into four colleges: College of Arts and Letters; College of Social Sciences, Mathematics and Education; College of Natural and Health Sciences; and Sykes College of Business, which is accredited at the undergraduate and graduate levels by the Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB).[21]

The University of Tampa has an Honors Program, which "allows students to go beyond the classroom and regular course work to study one-on-one with faculty through enrichment tutorials, Honors Abroad, internships, research and classroom-to-community outreach."[22]

UT also offers a host of international study-abroad options led by UT professors.[23] The university is an associate member of the European Council of International Schools (ECIS).

The Lowth Entrepreneurship Center at The University of Tampa has been awarded the Entrepreneurship Teaching and Pedagogical Innovation Award by the Global Consortium of Entrepreneurship Centers (GCEC).[24]

ROTC

For UT undergraduates desiring to be commissioned as officers in the U.S. Army following graduation, the campus is home to an Army ROTC unit.[25] For those students wishing to be commissioned as officers in the U.S. Navy, U.S. Marine Corps and U.S. Air Force upon graduation, cross-campus agreements are in place for UT students to affiliate with either the Naval ROTC unit or Air Force ROTC Detachment 158 at the University of South Florida.

Rankings

Forbes ranks The University of Tampa as #433 in the United States overall as of 2019.[26] The U.S. News & World Report 2019 rankings placed UT as #20 in the Regional Universities South category, compared to the 149 other universities listed in that category.[27] In 2021 U.S. News & World Report ranked The University of Tampa #13 in the Regional Universities South category.[28] In 2022-23, UT was ranked #21 in the Regional Universities South category by U.S. News & World Report.[29]

Campus

UT's campus features 60 buildings on 110 landscaped acres. Plant Hall – a National Historic Landmark built in 1891 by Henry B. Plant – is a leading example of Moorish Revival architecture in the southeastern United States and a focal point of downtown Tampa. In addition to serving as a main location of classrooms and faculty and administrative offices, the building is also home to the Henry B. Plant Museum. The campus also includes the former McKay Auditorium, built in the 1920s and remodeled in the late 1990s to become the Sykes College of Business. In the last 16 years, UT has invested approximately $575 million in new residence halls, classrooms, labs and other facilities.[19]

The UT campus is relatively small for a school with 9,304 students. On its east side is the Hillsborough River, and Kennedy Boulevard is to the south. Recent expansions have seen the campus grounds move northward and eastward following purchases of sections of Tampa Preparatory School and vacant lots across the east-side railroad tracks.

Although the university is located in a major metropolitan area, palm trees, stately oaks, rose bushes and azaleas can be found in abundance on campus. UT's grounds include Plant Park, a landscaped, palm-tree-lined riverside area in front of Plant Hall's main entrance. It features cannons from Tampa's original harbor fort and the Sticks of Fire sculpture. It also is home to the oak tree under which Hernando de Soto supposedly met the chief of the local Native American tribes upon first coming ashore at what is now Tampa. The campus also includes the former Florida State Fair grounds, where legend has it Babe Ruth hit a home run of 630 feet (190 m), the longest of his career.

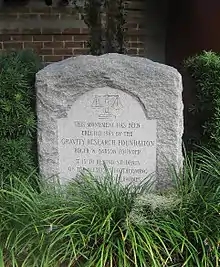

UT is also one of few schools with an anti-gravity monument from Roger Babson's Gravity Research Foundation. The "Anti-Gravity Rock", as it is commonly referred to, is located on the crosswalk between the College of Business parking lot and the Macdonald–Kelce Library, at the very end of the Science wing of Plant Hall. The stone's location is somewhat ironic, yet appropriate, given that Babson's scientific views were shared by few if any scientists.

Residence halls

About 60% of full-time UT students live on the university's main campus. All but 3 of the 12 on-campus residence halls have been built since 1998.

Straz Hall and Palm Apartments offer apartment-style living, with each student having a private room but sharing a bathroom, kitchen and common area with three others. Five dorms, Smiley Hall, McKay Hall, Boathouse, Austin Hall and Vaughn Center, offer traditional dormitory arrangements, with two or three students in a connected suite sharing a bathroom and open living areas. Three halls, Brevard Hall, Morsani Hall and Jenkins Hall, offer a hybrid package with students sharing a common area but without a kitchen. Finally, Urso Hall provides students with what is essentially a studio apartment, a private suite consisting of a bed, closet, kitchenette and restroom. Every residence hall also offers a small assortment of private single rooms.

The Barrymore Hotel, located about 1 mile (1.6 km) from campus, also houses some students.[30] Two students typically stay in each room, which is equipped with two double beds, a bathroom and closet space. UT's wireless internet is available, along with cable television. A shuttle bus provides transportation to/from campus, or students can take the 15-minute walk.

Facilities

UT has about 50 computer labs and wireless Internet access across campus. The Sykes College of Business, in addition to housing a computer lab, has a stock market lab, equipped with terminals and plasma screen TVs for teaching finance majors the intricacies of the stock market. The College of Natural and Health Sciences maintains a remote marine science research center on Tampa Bay with extensive equipment including research vessels used by students and faculty for studying the ecosystems of Tampa Bay and the Gulf of Mexico.

The Macdonald–Kelce Library houses more than 275,000 books and 65,181 periodicals, as well as online research databases, a computer lab, study rooms and special collections, including Florida military materials, old and rare books, and local history and UT archives. The library also offers reference assistance and bibliographic instruction, interlibrary loans and reserve materials.[31]

For student recreation there is a new Fitness and Recreation Center, a two-floor, 60,000 square foot space featuring six exercise rooms, including indoor cycling, functional training and yoga.[32] There is also an on-campus aquatic center, the pool has a deep swimming section for scuba classes; it is open to students at limited times. UT offers sand volleyball courts, outdoor basketball courts, a fully equipped intramural sports gym with indoor courts, intramural softball fields, tennis courts, a ropes course, a soccer field, a running track, intramural baseball fields, a multi-use intramural field and a fully equipped workout center.[33] The university has been recognized for being a green business, by the US Green Building Council with several facilities holding an LEED certification.[34]

UT's theater department hosts student produced and acted plays across Kennedy Boulevard in the historic Falk Theatre. Falk also hosts large academic gatherings, student productions and concerts. In 2003 Falk Theatre was featured as a setting in the film The Punisher.

The non-denominational Sykes Chapel and Center for Faith and Values includes a 250-seat main hall, meeting and meditation rooms, pipe organ by Dobson Pipe Organ Builders, a plaza and 60-bell musical sculpture/fountain.[35]

The Bob Martinez Athletics Center received substantial upgrades during recent improvements throughout the university.[36]

Students

UT has approximately 10,566 students from 50 U.S. states and 132 countries. A significant number of students come from northern and northeastern states while about 15% of the student body is made up of international students. Students from Florida make up about half of the student body. Sixty percent of full-time students live in campus housing.

Athletics

The University of Tampa competes at the Division II level in the Sunshine State Conference (SSC). The school's mascot is the Spartan.

Spartan teams have won a combined total of 19 NCAA Division II National Titles, as follows: seven in baseball (1992, 1993, 1998, 2006, 2007, 2013, 2015, 2019), three in men's soccer (1981, 1994, 2001), two in golf (1987, 1988), three in volleyball (2006, 2014, 2018), one in beach volleyball (2019), one in women's soccer (2007), and one in Men's Lacrosse (2022)[37].[38]

UT presently competes in baseball, men's and women's basketball, beach volleyball, men's and women's cheerleading/dance, men's and women's cross country, men's and women's golf, men's and women's lacrosse, women's rowing, men's and women's soccer, softball, men's and women's swimming, women's tennis, men's and women's track, and women's volleyball.[38] UT athletes are among the top in the SSC in terms of All-American, All-Region, and All-Conference players along with numerous Commissioner's Honor Roll recipients.[39] The school has recently built dedicated stadiums for baseball, softball, soccer, track, and lacrosse that rival many Division I facilities. The men's club hockey team competes in the American Collegiate Hockey Association (ACHA). UT's equestrian team competes in the Intercollegiate Horse Show Association (IHSA).

Tampa Spartans football

The University of Tampa fielded the first college football team in the Tampa Bay area in 1933, soon after the school was founded. The "Tampa U" Spartans played at Plant Field their first three seasons, which had to be shared with many community events. In 1936, the school built its own facility in Phillips Field, which was named for local businessman I. W. Phillips, who donated a plot of land adjacent to the university for the stadium site.[40] In 1967, the Spartans moved up to NCAA Division I and moved their home field to newly built Tampa Stadium. The Spartans produced several NFL stars, such as John Matuszak and Freddie Solomon, and had a sizeable local following. However, the school had only about 2000 students in the early 1970s and struggled to afford the expenses of a major college football program.

When Tampa was awarded a new NFL franchise in 1974 (the soon to be named Tampa Bay Buccaneers), UT president B.D. Owens reported to the university's board that attendance at Spartans' games was likely to decrease, further impacting the school's finances. Accordingly, the board voted to fold the Spartan football program after the 1974 season.[14] The football program finished with an all-time record of 201–160–12.[41]

Student media

UT's undergraduate literary journal, Neon (originally Quilt), has been published by students since 1978.[42] Neon hosts numerous events throughout the academic year, including open mic nights, which are open to the public. Yearly, Neon hosts a prominent writer for "Coffeehouse Weekend." Recent visitors have included Kate Greenstreet and Dorothy Allison.

Other student-run publications include The Minaret newspaper, The Moroccan yearbook, and Splice Journal, which showcases student work in communication, art and culture.[43]

UT also has a student radio station (WUTT 1080) and television station (UT-TV).

Fraternities and sororities

The history of UT and its sororities and fraternities is somewhat contentious. The first Greek groups appeared on campus in the early 1950s and by the 1970s they had developed a thriving culture that included the tradition of having a rock on campus with the organizations' letters on it. However, by the late 1970s all Greek organizations were removed from UT and all Greek housing was destroyed or converted for other uses.

Despite these obstacles, Greeks resurged on campus in the mid-1980s. UT students formed local Greek groups, developing traditions and rituals anew. After these homegrown groups had established a campus presence, many lobbied national organizations, particularly those on campus before the ban, to assimilate them. In this way, Greek life returned to UT and with many of the same fraternities and sororities of the past. Today, about 20 percent of UT's undergraduates are members of 28 fraternities and sororities.[44]

Notable alumni and attendees

Notable people who attended the University of Tampa include:

- Braulio Alonso, educator, first Hispanic president of the National Education Association

- Rod Blagojevich, governor of Illinois

- Steve Boyett, author and DJ

- Alejandra Caraballo, civil rights attorney and LGBTQ advocate

- Chyna (Joan Laurer), actress and professional wrestler

- Cr1TiKaL (Charles White), entertainer and Internet celebrity

- Danielle Dixson, marine ecologist at the University of Delaware

- Connie May Fowler, author

- Dick Greco, four-time mayor of Tampa

- Amy Hill Hearth, author

- Dennis James Kennedy, Presbyterian pastor and author

- Bob Martinez, mayor of Tampa and 40th governor of Florida

- Tino Martinez, Major League Baseball player

- John Matuszak, National Football League player and actor

- Brett James McMullen, retired United States Air Force General Officer

- Leon McQuay, National Football League player

- Pascal Milien, professional football player

- Juan Camilo Mouriño, former Secretary of the Interior of Mexico

- Paul "Mr. Wonderful" Orndorff, professional wrestler

- Lou Piniella, Major League Baseball player

- Pete Peterson, retired U.S. Air Force colonel, fighter pilot, Vietnam War prisoner of war, former U.S. Representative from Florida and former U.S. ambassador to Vietnam

- "Dirty" Dick Slater, professional wrestler

- Freddie Solomon, National Football League player

See also

References

- ↑ "Commission on Colleges". Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- ↑ center, member. "Member Center". Archived from the original on 9 November 2015. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- ↑ "2019 Endowment" Retrieved August 20, 2019.

- ↑ "University Profile". Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- ↑ The University of Tampa Brand Guidelines (PDF). Retrieved 2017-04-01.

- ↑ Iorio, Pam (18 August 2013). "Minarets were a steal for Tampa". The Tampa Tribune. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- ↑ "Hillsborough High School: About Our School". official website of Hillsborough High School. 2017-10-03.

- 1 2 3 "University of Tampa - History". Official website of the University of Tampa.

- ↑ "UT Renames Main Campus Street After Founder and First President". www.ut.edu. University of Tampa. Retrieved September 22, 2020.

- ↑ "Tampa Bay Hotel---American Latino Heritage: A Discover Our Shared Heritage Travel Itinerary". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ↑ "Grant Award Agreement with University of Tampa" (PDF). Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ↑ "AACSB-Accredited Schools Worldwide". Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Colavecchio, Shannon (2 October 2006). "UT celebrates 75 years". The St. Petersburg Times.

- 1 2 "Tampa Cancels Football Program February 28, 1975 - Newspapers.com". The Orlando Sentinel. 28 February 1975. p. 33. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- ↑ Guzzo, Paul (16 October 2017). "Bruce Samson, who turned around the University of Tampa, dies at 79". The Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved 16 October 2017.

- ↑ Linda Gibson (2000). "University of Tampa lands $28-million gift". St. Petersburg Times. Retrieved 2010-02-28.

- ↑ "The University of Tampa - Tampa, Florida - Office of the President - Dr. Ronald L. Vaughn". www.ut.edu. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- ↑ "University of Tampa". US News. 2016. Retrieved 2016-03-17.

- 1 2 "The University of Tampa - Tampa, Florida - UT Profile". Retrieved 17 August 2015.

- ↑ "University of Tampa adding new building for cybersecurity majors". Retrieved 17 August 2015.

- ↑ "Forty-Nine Business Schools Extend their AACSB Accreditation in Business or Accounting". Retrieved 17 August 2015.

- ↑ The University of Tampa – Honors Program. Ut.edu. Retrieved on 2012-05-08.

- ↑ "The University of Tampa - International Programs - Education Abroad". Retrieved 17 August 2015.

- ↑ "2015 GCEC Award Winners". Retrieved 17 March 2016.

- ↑ "The University of Tampa - Tampa, Florida - Army ROTC". www.ut.edu. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ↑ Forbes College Rankings.

- ↑ U.S. News & World Report.

- ↑ "University of Tampa". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved December 15, 2020.

- ↑ "University of Tampa U.S. News & World Report Best Colleges ranking". U.S. News & World Report. September 12, 2022.

- ↑ University of Tampa residence halls, retrieved July 19, 2012

- ↑ "University of Tampa – Macdonald-Kelce Library". Ut.edu (1969-10-19). Retrieved on 2012-05-08.

- ↑ "The University of Tampa - New Fitness Center". www.ut.edu. Retrieved 2016-10-05.

- ↑ "The University of Tampa - Tampa, Florida - McNiff Fitness Center". Retrieved 17 August 2015.

- ↑ "UT Recognized as an Outstanding Green Business".

- ↑ University of Tampa Sykes Chapel. Ut.edu. Retrieved on 2012-05-08.

- ↑ "UT athletics center upgraded". Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- ↑ "Tampa wins 2022 DII men's lacrosse national championship". Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- 1 2 "Spartan Baseball: Seven-Time National Champions!". Retrieved 17 August 2015.

- ↑ "About UT Athletics". Tampa Spartans. Retrieved 23 October 2018.

- ↑ "Interview with A.C. Howell".

- ↑ "Tampa Spartans Football Record By Year". College Football at Sports-Reference.com. Retrieved 2021-10-12.

- ↑ "Quilt Literary & Arts Journal". University of Tampa.

- ↑ "The University of Tampa - Tampa, Florida - Student Publications and Media". Retrieved 17 August 2015.

- ↑ "The University of Tampa - Greek Life - Chapters". Retrieved 17 August 2015.