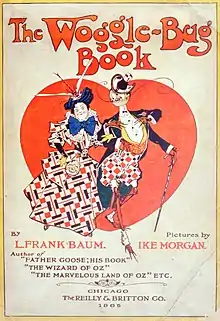

first edition cover | |

| Author | L. Frank Baum |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | Ike Morgan |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Children's book Humor Fantasy |

| Publisher | Reilly & Britton |

Publication date | 1905 |

| Media type | |

| Pages | 48 pp. (unpaged) |

The Woggle-Bug Book is a 1905 children's book, written by L. Frank Baum, creator of the Land of Oz, and illustrated by Ike Morgan. It has long been one of the rarest items in the Baum bibliography.[1] Baum's text has been controversial for its use of ethnic humor stereotypes.

Background

The book grew out of another promotional project, Queer Visitors from the Marvelous Land of Oz (1904-5), a popular comic strip that promoted Baum's second Oz book, The Marvelous Land of Oz (1904). The comic strip, written by Baum and illustrated by Walt McDougall, brought Oz characters including the Scarecrow, the Tin Woodman, and others[2] to the United States for various humorous adventures. The Woggle-Bug Book employs the same concept: H. M. Woggle-Bug, T. E.[3] is shown maladjusted to life in an unnamed American city. The book's artist, Ike Morgan, was a Chicago cartoonist who had earlier provided illustrations for Baum's American Fairy Tales (1901).

Baum's Woggle-Bug was a popular character at the time; he "became something of a national fad and icon...."[4] There were Woggle-Bug postcards and buttons, a Woggle-Bug song, and a Woggle-Bug board game from Parker Brothers.[5] Baum and Morgan's picture book was published in January 1905, to help publicize a new musical play, The Woggle-Bug, that was being mounted that year. (The play flopped.) The book was copiously illustrated, with pictures and text alternating on recto and verso pages; it was printed in bright colors in a large format, eleven by fifteen inches.

Plot

The Woggle-Bug Book features the broad ethnic humor that was accepted and popular in its era, and which Baum employed in various works.[6] The Woggle-Bug, who favors flashy clothes with bright colors (he dresses in "gorgeous reds and yellows and blues and greens" and carries a pink handkerchief), falls in love with a gaudy "Wagnerian plaid" dress that he sees on a mannequin in a department store window. Being a woggle bug, he has trouble differentiating between the dress and its wearers, wax or human. The dress is on sale for $7.93 ("GREATLY REDUCED" reads the tag). The Bug works for two days as a ditchdigger (he earns double pay since he digs with four hands) for money to buy the dress.

He arrives too late, though; the dress has been sold, and makes its way through the second-hand market. The Bug pursues his love through the town, ineptly courting the women (Irish, Swedish, and African-American, plus one Chinese man) who have the dress in turn. His pursuit eventually leads to an accidental balloon flight to Africa. There, menacing Arabs want to kill the Woggle-Bug, but he convinces them that his death would bring bad luck. In the jungle he falls in with the talking animals that are the hallmark of Baum's imaginative world.

In the end, the Bug makes his way back to the city, with a necktie made from the dress's loud fabric. He wisely reconciles himself to his fate:

- "After all, this necktie is my love – and my love is now mine forevermore! Why should I not be happy and content?"

There are plot exploits elements that occur in other Baum works: An accidental balloon flight took the Wizard to Oz in Baum's most famous book; hostile Arabs are a feature of John Dough and the Cherub (1906).

Humor

The ethnic humor in The Woggle-Bug Book is crude by modern standards; one critic has called it "egregious."[7] At its best the book also delivers zany absurdities:

- Now the greatest aversion the Arabs have is to be chewed by a crocodile, because these people usually roam over the sands of the desert, where to meet an amphibian is simply horrible....

In Africa, the Bug meets a charming Miss Chimpanzee who guides him through the intricacies of jungle life. Miss Chim has a low opinion of human beings:

- "Those horrid things they call men, whether black or white, seem to me the lowest of all created beasts."

- "I have seen them in a highly civilized state," replied the Woggle-Bug, "and they're really further advanced than you might suppose."

The Bug has his fortune told by a hippopotamus:

- "You think you have won," continued the Hip; "but there are others who have 1, 2. You have many heart throbs before you, during your future life. Afterward I see no heart throbs whatever. Forty cents, please."

The king of this jungle is not a lion but a weasel, who rejects flattery and accepts only insults and face slaps. His kingdom is guarded by bears with guns, who form a "bearier" or "bearicade." They "oblige all strangers to paws."

Later editions

After decades out of print, a black and white facsimile edition of The Woggle-Bug Book was released in 1978.[8] The text of The Woggle-Bug Book was included as the final chapter of The Third Book of Oz (1989), a slightly edited reprint of the Queer Visitors stories. (A later edition of this, called The Visitors from Oz, was published by Hungry Tiger Press with minimal editing in 2005.) A larger facsimile that excluded the cover artwork was reprinted in Oz-story Magazine in 1999.[9] Another edition appeared in 2008.

References

- ↑ Douglas G. Greene and Peter E. Hanff, Bibliographia Oziana: A Concise Bibliographical Checklist of the Oz Books of L. Frank Baum, revised and enlarged edition, Kinderhook, IL, International Wizard of Oz Club, 1988.

- ↑ Also Jack Pumpkinhead, the Sawhorse, The Gump, and the Woggle-Bug. Jack Snow, Who's Who in Oz, Chicago, Reilly & Lee, 1954; New York, Peter Bedrick Books, 1988; pp. 86, 105-6, 186-7, 214.

- ↑ Who's Who in Oz, pp. 239-40.

- ↑ Jack Zipes, When Dreams Came True: Classic Fairy Tales and Their Tradition, second edition, CRC Press, 2007; p. 202.

- ↑ David L. Greene and Dick Martin, The Oz Scrapbook, New York, Random House, 1977; p. 22.

- ↑ See Father Goose and Father Goose's Year Book for examples. For the anti-racist side of Baum, see Sam Steele's Adventures on Land and Sea.

- ↑ Katharine M. Rogers, L. Frank Baum, Creator of Oz: A Biography, New York, St. Martin's Press, 2001; p. 272.

- ↑ From Scholars' Facsimiles and Reprints, of Delmar, NY; with an introduction by Douglas G. Greene.

- ↑ Oz-story Magazine, No. 5 (October 1999), pp. 77-124.