| Third Taiwan Strait Crisis 台灣海峽飛彈危機 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Chinese Civil War | |||||||

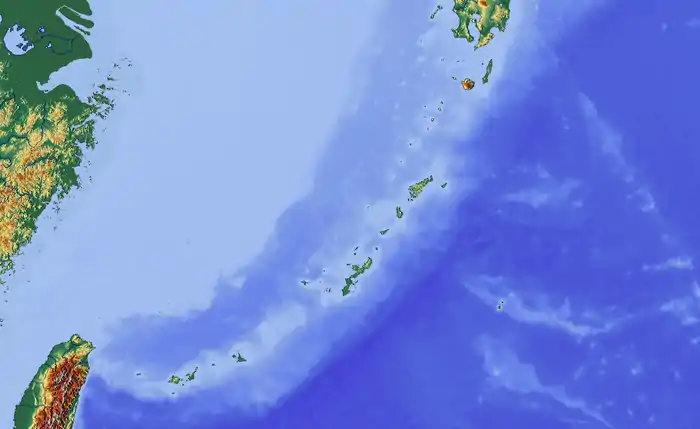

Taiwan Strait | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

MIM-104 Patriot, MIM-23 Hawk, F-5 Tiger, F-CK-1, F-104 Starfighter, Knox-class frigate, Oliver Hazard Perry-class frigate, etc. USS Independence (CV-62), USS Nimitz (CVN-68), USS Belleau Wood (LHA-3), USS Bunker Hill (CG-52), etc. |

| ||||||

The Third Taiwan Strait Crisis, also called the 1995–1996 Taiwan Strait Crisis or the 1996 Taiwan Strait Crisis, was the effect of a series of missile tests conducted by the People's Republic of China (PRC) in the waters surrounding Taiwan, including the Taiwan Strait from 21 July 1995 to 23 March 1996. The first set of missiles fired in mid-to-late 1995 were allegedly intended to send a strong signal to the Republic of China government under President Lee Teng-hui, who had been seen as "moving its foreign policy away from the One-China policy", as claimed by PRC.[1] The second set of missiles were fired in early 1996, allegedly intending to intimidate the Taiwanese electorate in the run-up to the 1996 presidential election.

Lee's 1995 visit to Cornell

The crisis began when President Lee Teng-hui accepted an invitation from his alma mater, Cornell University to deliver a speech on "Taiwan's Democratization Experience". Seeking to diplomatically isolate the Republic of China, the PRC opposed such visits by ROC (Taiwanese) leaders. A year earlier, in 1994, when President Lee's plane had stopped in Honolulu to refuel after a trip to South America, the U.S. government under President Bill Clinton refused Lee's request for a visa. Lee had been confined to the military airfield where he landed, forcing him to spend a night on his plane. A U.S. State Department official called the situation "embarrassing" and Lee complained that he was being treated as a second-class leader.

After Lee had decided to visit Cornell, U.S. Secretary of State Warren Christopher assured PRC Foreign Minister Qian Qichen that a visa for Lee would be "inconsistent with [the U.S.'s] unofficial relationship [with Taiwan]." However, the humiliation from Lee's last visit caught the attention of many pro-Taiwan figures in the U.S. and this time, the United States Congress acted on Lee's behalf. In May 1995, a concurrent resolution asking the State Department to allow Lee to visit the U.S. passed the House on 2 May with a vote of 396 to 0 (with 38 not voting), and the Senate on 9 May with a vote of 97 to 1 (with 2 not voting).[2] The State Department relented on 22 May 1995. Lee spent 9–10 June 1995, in the U.S. at a Cornell alumni reunion as the PRC state press branded him a "traitor" attempting to "split China".[1]

PRC military response

The People's Republic of China government under CCP general secretary Jiang Zemin was furious over the U.S.'s policy reversal. On 7 July 1995, PRC responded, the Xinhua News Agency announced missile tests would be conducted by the People's Liberation Army (PLA) and argued that this attitude would endanger the peace and safety of the region (Mainlander refers to it as the fourth Taiwan strait crisis[3]). At the same time, the PRC mobilized forces in Fujian. In the later part of July and early August, numerous commentaries were published by Xinhua and the People's Daily condemning Lee and his cross-strait policies.

Another set of missile firings, accompanied by live ammunition exercises, occurred from 15 to 25 August 1995. Naval exercises in August were followed by highly publicized amphibious assault exercises in November.

Initial U.S. military response

The U.S. government responded by staging the biggest display of American military might in Asia since the Vietnam War.[4] In July 1995, USS Belleau Wood (LHA-3) transited the Taiwan Strait, followed by the USS O'Brien (DD-975) and USS McClusky FFG-41 on 11–12 December 1995. Finally on 19 December 1995, the USS Nimitz (CVN-68) and her battle group passed through the straits.[5]

1996 tensions and Taiwan election

Beijing intended to send a message to the Taiwanese electorate that voting for Lee Teng-hui in the 1996 presidential election on 23 March meant war. A third set of PLA tests from 8 March to 15 March (just before the election), sent missiles within 46 to 65 km (25 to 35 nmi) (just inside the ROC's territorial waters) off the ports of Keelung and Kaohsiung. Over 70 percent of commercial shipping passed through the targeted ports, which were disrupted by the proximity of the tests.[6][7] Flights to Japan and trans-Pacific flights were prolonged by ten minutes because airplanes needed to detour away from the flight path. Ships traveling between Kaohsiung and Hong Kong had to take a two-hour detour.

On 8 March 1996, also a presidential election year in the U.S., President Clinton announced that the USS Independence CV-62 and her Carrier Battlegroup (Carrier Group Five),[8] returning to Japan from its visit to the Philippines, would deploy to international waters near Taiwan.[9] According to the Washington Post, that same day; the USS Bunker Hill CG-52 (which had detached from the Independence Battlegroup) along with a RC-135 Intelligence aircraft monitored the launch of 3 CSS-6 (DF-15) missiles from the PRC, two of them into shipping lanes near Kaohsiung and one fired directly over Taipei into a shipping lane near Keelung.[10]

On the following day, the PRC announced live-fire exercises to be conducted near Penghu from 12 to 20 March. On 11 March, the U.S. dispatched USS Nimitz CVN-68 and her battlegroup, Carrier Group Seven,[11] which steamed at high speed from the Persian Gulf. Tensions rose further on 15 March when Beijing announced a simulated amphibious assault planned for 18–25 March. Nimitz and her battle group, along with Belleau Wood, sailed through the Taiwan Strait, while Independence did not.[12][13]

Aftermath

Sending two carrier battle groups showed not only a symbolic gesture towards the ROC, but a readiness to fight on the part of the U.S. The ROC government and Democratic Progressive Party welcomed America's support, but staunch unificationist presidential candidate Lin Yang-kang and the PRC decried "foreign intervention."

Aware of U.S. Navy carrier battle groups' credible threat to the PLA Navy, the PRC decided to accelerate its military buildup. Soon the People's Republic ordered Sovremenny-class destroyers from Russia, a Cold War-era class designed to counter U.S. Navy carrier battle groups, allegedly in mid-December 1996 during the visit to Moscow by Chinese Premier Li Peng. The PRC subsequently ordered modern attack submarines (Kilo class) and warplanes (76 Su-30MKK and 24 Su-30MK2) to counter the U.S. Navy's carrier groups.

The PRC's attempts at intimidation were counterproductive. Arousing more anger than fear, it boosted Lee by 5% in the polls, earning him a majority as opposed to a mere plurality.[14] The military tests and exercises also strengthened the argument for further U.S. arms sales to the ROC and led to the strengthening of military ties between the U.S. and Japan, increasing the role Japan would play in defending Taiwan.

During the military exercises in March, there were preoccupations in Taiwan that the PRC would occupy some small islands controlled by Taiwan, causing panic among many citizens. Therefore, many flights from Taiwan to the United States and Canada were full. The most likely target was Wuqiu (Wuchiu), then garrisoned by 500 soldiers. The outlying islands were placed on high alert.[15] The then secretary general of the National Security Council of Taiwan, Ting Mao-shih, flew to New York to meet Samuel Berger, Deputy National Security Advisor of the United States.[16]

U.S. order of battle (March 1996 – May 1996)

_underway_at_sea_on_10_March_1996.jpeg.webp)

U.S. 7th Fleet

- Carrier Group 5 - Independence CVBG - (East China Sea)

- USS Independence CV-62 (Forrestal Class Carrier)

- Carrier Air Wing 5 - NF

- VF-154 Black Knights - F-14A Tomcat (TARPS equipped)

- VFA-192 Golden Dragons - F/A-18C Hornet

- VFA-195 Dambusters - F/A-18C Hornet

- VA-115 Eagles - A-6E SWIP Intruder

- VAQ-136 Gauntlets - EA-6B Prowler

- VS-21 Red Tails - S-3B Viking

- VAW-115 Liberty Bells - E-2C Hawkeye

- VQ-5 Sea Shadows Det.A - ES-3A Shadow

- HS-14 Chargers - SH-60F Oceanhawk/HH-60H Rescuehawk

- Carrier Air Wing 5 - NF

- USS Bunker Hill CG-52 (Ticonderoga Class VLS Cruiser) - (Detached from the Battlegroup southeast of the R.O.C.)[20]

- USS Hewitt DD-966 (Spruance Class VLS Destroyer)[20]

- USS O'Brien DD-975 (Spruance Class VLS Destroyer)[20]

- USS McClusky FFG-41 (Oliver H. Perry Class Frigate)* - After May 10, 1996*[21]

- USS Independence CV-62 (Forrestal Class Carrier)

- Carrier Group 7 - Nimitz CVBG - (Taiwan Strait)

- USS Nimitz CVN-68 (Nimitz Class Carrier)

- Carrier Air Wing 9 - NG

- VF-24 Fighting Renegades - F-14A Tomcat

- VF-211 Checkmates - F-14A Tomcat (TARPS equipped)[22]

- VFA-146 Blue Diamonds - F/A-18C (Night Attack) Hornet

- VFA-147 Argonauts - F/A-18C (Night Attack) Hornet

- VA-165 Boomers - A-6E SWIP Intruder

- VAQ-138 Yellow Jackets - EA-6B Prowler

- VS-33 Screwbirds - S-3B Viking

- VAW-112 Golden Hawks - E-2C Hawkeye

- VQ-5 Sea Shadows Det.C - ES-3A Shadow

- HS-8 Eightballers - SH-60F Oceanhawk/HH-60H Rescuehawk

- Carrier Air Wing 9 - NG

- USS Port Royal CG-73 (Ticonderoga Class VLS Cruiser)

- USS Oldendorf DD-972 (Spruance Class VLS Destroyer)[23]

- USS Callaghan DD-994 (Kidd Class Destroyer)[24]

- USS Ford FFG-54 (Oliver H. Perry Class Frigate)[25]

- USS Nimitz CVN-68 (Nimitz Class Carrier)

- Amphibious Squadron 11 - Belleau Wood ARG[26][27] - (Taiwan Strait)

Subsequent prosecutions

In 1999, Major General Liu Liankun, a top Chinese military logistics officer, and his subordinate Senior Colonel Shao Zhengzhong were arrested, court-martialed and executed for disclosing to Taiwan that the missiles had unarmed warheads despite the Chinese government's claims.[28]

Unofficial forewarning

According to Sankei Shimbun series "Secret Records on Lee Teng-hui" dated 1 April 2019, Tseng Yong-hsien, Lee's National Policy Adviser, received a direct message from China official in early July 1995; "Our ballistic missiles will be launched toward Taiwan a couple of weeks later, but you guys don't have to worry." This was communicated to Lee soon after, to prevent escalation. Tseng, as an envoy of Lee, had met President Yang Shangkun in 1992 and had a secret connection with Ye Xuanning, Head of the Liaison Department of the PLA.[29]

See also

References

- 1 2 "Taiwan's President Speaks at Cornell Reunion Weekend". Cornell University. Archived from the original on 10 July 2012. Retrieved 20 July 2010.

- ↑ H.Con.Res. 53. Senator Bennett Johnston, Jr. (D-LA) was the lone "nay" voter

- ↑ 回顾惊心动魄的5次台海危机 [A review of the five thrilling Taiwan Strait crises]. taiwan.cn. China Taiwan Net. china.com. 26 February 2008. Archived from the original on 8 September 2018.

- ↑ "US Role". BBC News. Archived from the original on 28 February 2015. Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- ↑ Roper, John C. (26 January 1996). "U.S. aircraft carrier in Asia 'routine'". UPI. Washington, D.C. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ↑ Li, Xiaobing (2012). China at War: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 445. ISBN 978-1-59884-415-3. Retrieved 28 March 2015.

- ↑ "U.S. Navy ships to sail near Taiwan". CNN. 10 March 1996. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 28 March 2015.

- ↑ USS Independence (CV-62) WestPac Cruise Book 1996. Walsworth Publishing Company. 1996.

- ↑ USS Independence CV-62 1996 Cruise Book on YouTube

- ↑ Gellman, Barton (21 June 1998). "U.S. AND CHINA NEARLY CAME TO BLOWS IN '96". The Washington Post.

- ↑ USS Nimitz CVN-68 WestPac Cruise Book 1994-96. United States Navy. 1996.

- ↑ Elleman, Bruce (2014). Taiwan Straits: Crisis in Asia and the Role of the U.S. Navy. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 130. ISBN 978-0-8108-8890-6.

- ↑ Copper, John (1998). Taiwan's Mid-1990s Elections: Taking the Final Steps to Democracy. Greenwood. p. 116. ISBN 978-0-275-96207-4.

- ↑ Baron, James (18 August 2020). "The Glorious Contradictions of Lee Teng-hui". The Diplomat. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- ↑ "Report: China expected to attack island". The Times-News. 25 February 1996. p. C6.

The most likely target would be Wuchiu, above five miles off the eastern coast of China, the report said. The island has a garrison of 500 soldiers. To prepare for an attack, outlying islands have been placed on high alert, it said.

- ↑ Xin, Qiang (2009). "迈向"准军事同盟":美台安全合作的深化与升级(1995~2008)" [Moving toward a "Quasi-Military Alliance": The Deepening and Upgrading of US–Taiwan Security Cooperation (1995–2008)]. American Studies Quarterly (in Chinese) (4). Archived from the original on 4 June 2013. Retrieved 5 January 2013.

- 1 2 硝烟滚滚震慑"台独"——东南沿海演习始末(下) [Gunpowder smoke deters "Taiwanese independence" — the beginning and end of the southeast coastal exercise (part 2)] (in Chinese). China Central Television. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- ↑ 1996年3月20日 中国人民解放军在东海和南海进行海空实弹演习 [20 March 1996: The Chinese People's Liberation Army conducts sea and air live ammunition exercises in the East China Sea and the South China Sea]. people.com.cn (in Chinese). 19 March 2009. Archived from the original on 30 June 2010. Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- ↑ "zh:1996年3月18日 中国人民解放军在台湾海峡进行陆海空联合演习" [18 March 1996: The Chinese People's Liberation Army conducts joint land, sea and air exercises in the Taiwan Strait]. people.com.cn (in Chinese). 16 March 2009. Archived from the original on 22 May 2013. Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- 1 2 3 USS Bunker Hill CG-52 Command Operations Report 1996 (PDF). United States Navy. 1996.

- ↑ USS McClusky FFG-41 Command Operations Report - 1996 (PDF). United States Navy. 1996.

- ↑ "VF-211 Squadron History". www.topedge.com. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ↑ "CNN - Ships of the U.S. Taiwan deployment - Mar. 13, 1996". edition.cnn.com. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ↑ "Callaghan II (DDG-994)". public2.nhhcaws.local. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ↑ USS Ford FFG-54 - Command Operations Report 1996 (PDF). United States Navy. 1996.

- ↑ US Marines Corps Operational Summary February 1996 (PDF). United States Marine Corps. 1996.

- ↑ US Marines Corps Operational Summary April 1996 (PDF). United States Marine Corps. 1996.

- ↑ Lim, Benjamin Kang (14 September 1999). "China executes two for spying for Taiwan". The Washington Post. Retrieved 26 September 2021.

- ↑ The series was later published as a book: 李登輝秘録 (Ri Touki Hiroku) ISBN 978-4819113885.

Further reading

- Bush, Richard C.; O'Hanlon, Michael E. (2007). A War Like No Other: The Truth About China's Challenge to America. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-98677-5.

- Bush, Richard C. (2005). Untying the Knot: Making Peace in the Taiwan Strait. Washington, D.C.: The Brookings Institution. ISBN 978-0-8157-1288-6.

- Lilley, James R.; Downs, Chuck, eds. (1997). Crisis in the Taiwan Strait (PDF). Published in cooperation with The American Enterprise Institute. Fort McNair, Washington, D.C.: National Defense University Press. ISBN 978-1-57906-000-8. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 August 2022.

- Carpenter, Ted Galen (2005). America's Coming War with China: A Collision Course over Taiwan. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 1-4039-6841-1.

- Cole, Bernard D. (2006). Taiwan's Security: History and Prospects. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-36581-3.

- Copper, John F. (2006). Playing with Fire: The Looming War with China over Taiwan. Praeger Security International. ISBN 0-275-98888-0.

- FAS; NRDC (November 2006). Chinese Nuclear Forces and U.S. Nuclear War Planning (PDF) (Report). Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 April 2022.

- Gill, Bates (2007). Rising Star: China's New Security Diplomacy. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press. ISBN 978-0-8157-3146-7.

- Ross, Robert S. (2000). "The 1995–96 Taiwan Strait Confrontation: Coercion, Credibility and the Use of Force". International Security. 25 (2): 87–123. doi:10.1162/016228800560462. JSTOR 2626754. S2CID 57560261.—This article traces in detail the course of the crisis and analyzes the state of Sino-American relations both before and after the crisis.

- Scobell, Andrew (1999). "Show of Force: The PLA and the 1995–1996 Taiwan Strait Crisis" (PDF). Shorenstein APARC. Archived from the original on 17 April 2018.

- Shirk, Susan (2007). China: Fragile Superpower: How China's Internal Politics Could Derail Its Peaceful Rise. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-530609-5.

- Thies, Wallace J.; Bratton, Patrick C. (2004). "When Governments Collide in the Taiwan Strait". Journal of Strategic Studies. 27 (4): 556–584. doi:10.1080/1362369042000314510. S2CID 154467802.

- Tsang, Steve, ed. (2006). If China Attacks Taiwan: Military Strategy, Politics and Economics. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-40785-0.

- Tucker, Nancy Bernkopf, ed. (2005). Dangerous Strait: the U.S.–Taiwan–China Crisis. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-13564-5.

- Moore, Gregory J. (2007). "The Roles of Misperceptions and Perceptual Gaps in the Taiwan Strait Crisis of 1995–1996". In Hua, Shiping; Guo, Sujian (eds.). China in the Twenty-First Century: Challenges and Opportunities. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 171–194. ISBN 978-1-4039-7975-9.