A tholos (pl.: tholoi; from Ancient Greek θόλος, meaning "conical roof"[1] or "dome"), in Latin tholus (pl.: tholi), is a form of building that was widely used in the classical world. It is a round structure with a circular wall and a roof, usually built upon a couple of steps (a podium), and often with a ring of columns supporting a conical or domed roof.

It differs from a monopteros (Ancient Greek:ὁ μονόπτερος from the Polytonic: μόνος, only, single, alone, and τὸ πτερόν, wing), a circular colonnade supporting a roof but without any walls, which therefore does not have a cella (room inside).[2] Both these types are sometimes called rotundas.

An increasingly large series of round buildings were constructed in the developing tradition of classical architecture until Late antiquity, which are covered here. Medieval round buildings are covered at rotunda. From the Renaissance onwards the classical tholos form had an enduring revival, now often topped by a dome, especially as an element in much larger buildings.

The tholos is not to be confused with the beehive tomb, or "tholos tomb" in modern terminology, a distinct form in Late Bronze Age Greece and other areas.[3] But many other round tombs and mausolea were built, especially for Roman emperors.

Classical world

Greece

In Ancient Greek architecture, the tholos form was used for a variety of buildings with different purposes. A few were round temples of Greek peripteral design completely encircled by a colonnade, but most served other functions, and some were architecturally innovative. According to A. W. Lawrence, by the 4th century BC, "their more or less secular functions gave partial exemption from the austere conventions that governed the design of temples".[4] No Greek tholos except the Choragic Monument of Lysicrates remains anything like intact, with most known only by excavation of their distinctive circular foundations, and other parts found lying on the site.[5]

The large building known as "the tholos" (but also "the parasol")[6] in the centre of Athens, just off the agora, at the least served as the dining-hall for the executive group of the boule, a council of 500 citizens chosen by lot from ten "tribes" to run daily affairs of the city, since a kitchen leads off the main circular hall. It may also have functioned as their debating chamber or prytaneion.[7] It was about 60 feet across, and built around 470 BC.[8]

Inside six columns supported the original conical roof, which seems have been covered with terracotta tiles round the lower parts, and perhaps bronze sheets higher up, leading to an acroterion at the apex, as seems to have been the case in the Philippeion. However this roof seems to have been destroyed by fire around 400 BC,[9] and was probably replaced by one using bronze sheets.[10] The original building, from not long after the Persian sack of Athens in 489–479 BC is "very plain",[11] with no exterior columns, showing "utter economy [in] its construction".[12]

The famous Tholos of Delphi was nearly 13.5 metres across. It has been dated to 370–360 BC. Its role remains unclear. There were 20 Doric columns around the exterior, and ten smaller Corinthian columns around the inside of the wall, rising up from a low stone bench. The building had "a more decorative treatment than would then have been permissable in a temple". It is now partially reconstructed at the site.[13]

Next to the temple at the Sanctuary of Asclepius, Epidaurus was "the finest of all tholoi according to ancient opinion". This was designed by the sculptor Polykleitos the Younger around 360 BC, and was 22 metres across. An inscription tells us the building was called the thymela or "place of sacrifice". It used the Corinthian order, still rather an innovation, for a ring of 14 columns inside, and the "extraordinary dainty" version of the capitals here was probably an influential model for later buildings. It may have introduced to the Corinthian the flower (or "rosette") touching the abacus in the centre of each face. Unlike a Greek temple, it had at least two windows flanking the doorway, and perhaps more higher up.[14]

Another Corinthian tholos was the small Choragic Monument of Lysicrates in Athens, about 334 BC, the first surviving building to use the Corinthian order on the outside – there was no inside.[15]

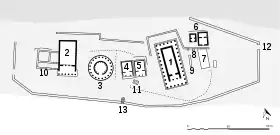

The Philippeion in the Altis of Olympia (c. 335 BC) was a circular memorial in limestone and marble, the rather cramped interior containing chryselephantine (ivory and gold) statues of Philip II of Macedon's family; himself, Alexander the Great, Olympias, Amyntas III and Eurydice I. Columns were Ionic around the outside, with engaged Corinthian half-columns inside.[16]

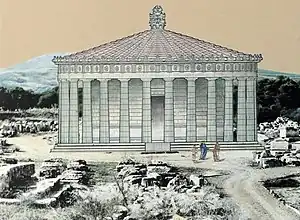

The largest Greek tholos, of uncertain function, was built in the Samothrace temple complex in the 260s BC. It is often called the Arsinoeum (or Arsinoëion, Arsinoë Rotunda), as a dedication tablet for the Ptolomeic Queen Arsinoe II of Egypt has survived. The sanctuary was a great Hellenistic centre of Greco-Roman mysteries, by this date becoming crowded with buildings.[17] The tholos was 20 metres across (from the lowest step) and, as reconstructed, 12.65 m high, with the lower parts of the wall blank, but small columns high up, where any windows were also placed.[18] One of the many reconstructions proposed by scholars was used as the basis of the Arlington Reservoir, Massachusetts, in the 1920s, functioning as a 2,000,000 gallon water tower.[19] The Befreiungshalle (1840s) near Kelheim, Bavaria, is a victory memorial on the same theme.

Remains of the Tholos of Athens

Remains of the Tholos of Athens Choragic Monument of Lysicrates, Athens, c. 334 BC

Choragic Monument of Lysicrates, Athens, c. 334 BC Foundation of the Arsinoeum at Samothrace, with the dedication slab at front

Foundation of the Arsinoeum at Samothrace, with the dedication slab at front Arlington Reservoir, Massachusetts, a 2,000,000 gallon water tower based on the Arsinoeum at Samothrace

Arlington Reservoir, Massachusetts, a 2,000,000 gallon water tower based on the Arsinoeum at Samothrace

Roman world

By far the most famous roofed round Roman building is the Pantheon, Rome. However this sharply differs from other classical tholoi in that it is entered though a very large flat temple front with a projecting portico with three rows of columns, while the rest of the exterior is a blank wall without columns or windows, so the circular form is rather obscured from the front until the visitor enters, and sees the enormous circular space.[21]

Temples of the goddess Vesta, which were usually small, were typically circular, but not all round temples were dedicated to her. The three best-known survivals, in or near Rome, were named "Temple of Vesta" by post-classical writers, in two cases without any good evidence. One is now usually called the Temple of Hercules Victor, while the old name continues to be used for the Temple of Vesta, Tivoli, in the absence of any firm evidence for the actual dedication – perhaps to the Tiburtine Sibyl. The identification of the Temple of Vesta, Rome, just next to the House of the Vestals, is secure.[22]

In Roman cities a tholos could often be found in the centre of the macellum (market), where it might have been where fish were sold. Other uses for the central tholos have been suggested, such as the place where official weights and measures were held for reference or as shrines to the gods of the market place. Some macella had a water fountain or water feature in the centre of their courtyard instead of a tholos structure.[23][24]

The Romans in effect developed a new form in the amphitheatre, of which the Colosseum in Rome is the largest, best known and best preserved. These were mostly oval rather than round and, like the semi-circular Roman theatres, un-roofed, except for the velarium, a cloth awning over some parts.[25]

.jpg.webp) Temple of Vesta, Rome, partly reconstructed

Temple of Vesta, Rome, partly reconstructed So-called Temple of Vesta, Tivoli

So-called Temple of Vesta, Tivoli_-2.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp) A tholos in the macellum at Leptis Magna, Libya

A tholos in the macellum at Leptis Magna, Libya

Tombs

The circular tumulus was the most common form of early Greek tomb, often revetted by a vertical or sloping stone wall round the base, a type still seen in abundance in Etruscan necropoli like the "Necropolis of the Banditaccia" at Cerveteri near Rome. The top was a mound of earth, with (in the Greek world) one or more upright stones at the summit. The Etruscan burial chambers were below ground level and rather large, crowded with family sarcophagi and grave goods (most surviving painted Greek vases come from Etruscan tombs).[26]

Local rulers around the edges of the Hellenic world constructed some significant tumulus tombs. The largest was that made about 600 BC for King Alyattes of Lydia (in modern Turkey), the father of Croesus, which dominates the elite cemetery site now called Bin Tepe. Herodotus visited it and says that stones at the summit recorded that it was constructed by the market traders, craftsmen and prostitutes of the nearby capital Sardis, the prostitutes making the largest contribution. It was 900 feet high, and nearly a quarter of a mile in diameter. A large mound, now reduced and slumped at the sides, remains, as does the barrel-vaulted passage to the looted tomb chamber at the centre.[27]

The so-called "Tomb of Tantalus", of a similar date, was fully faced in stone, with a diameter of 33.55 metres, and a height about the same. There was a vertical wall at the base, then a conical roof, much of which survived until 1835, when excavations led by Charles Texier using labour from the French Navy collapsed it. The passage leading to the rectangular burial chamber at the centre was entirely filled in with stones. The chamber was corbelled to form a pointed arch shape between two straight end walls. This was also the largest monument in a cemetery, now on the outskirts of İzmir.[28]

The Madghacen (or "Medracen") is a royal mausoleum, perhaps of the 3rd century BC, of the Berber Numidian kings in Numidia, Algeria, with a similar shape. Though independent, the Numidian kingdom was increasingly involved in Mediterranean power politics, and an architect familiar with classical architecture has surrounded the vertical section of wall at the base with engaged columns in the Doric order, "heavily proportioned and with smooth shafts, beneath a cavetto cornice". The whole exterior was, and very largely still is, covered with a stone facing, the straight cone of the upper part (except for a flat top) formed into steps, like the pyramids of Egypt.[29]

The Royal Mausoleum of Mauretania, long called the Tombeau de la Chrétienne ("Tomb of the Christian Woman"), is very similar, but a good deal larger and with Ionic columns around the base. It is the mausoleum of the thoroughly Romanized client king Juba II of Numidia and Mauretania (died 46 AD), and his queen Cleopatra Selene II, daughter of Cleopatra VII and Mark Antony. However, the design "seems definitely Greek".[30]

- Imperial Rome

Juba and Cleopatra Selene were probably still living in polite captivity in Rome when construction of the circular Mausoleum of Augustus began there around 28 BC. As (nearly) restored in the 21st century, there is an outer ring, then a space around the cylinder with the tomb-chamber, where the ashes of many of the Julio-Claudian dynasty were interred. Stairs lead up to the roof.[31] The large tombs of elite Roman families shared some of the characteristics of weekend cottages, with gardens, orchards, kitchens, and spacious apartments. Many liked to visit their family tomb on birthdays or anniversaries, for a family meal and day of reflection.[32]

The Mausoleum of Augustus measured 90 m (295 ft) in diameter by 42 m (137 ft) in height. The tomb was placed at the centre of a public park, long almost entirely built over, which included the Ara Pacis and other altars. From ancient writers it is clear that there was greenery, probably trees, growing on top of the upper parts, of an artificial mound or dome, which fell in and has not been restored to date.[33] The Casal Rotondo, of similar date with a diameter of 35 metres, is the largest tomb on the Appian Way outside Rome; who built it is now uncertain.[34] The Tomb of Caecilia Metella, daughter in law of the triumvir Crassus, is another large circular tomb.

Augustus set the precedent for a number of circular imperial tombs over the following centuries; some either became, or were built into, Christian churches, which have generally survived more intact. The largest is the Castel Sant'Angelo, built as the mausoleum for Hadrian (died 138), then converted into a castle. This had a garden on the flat roof. The Rotunda of Galerius in Thessaloniki, begun about 310, was probably intended as his mausoleum, and was later a church, then a mosque.[35] Only the underground parts of the Mausoleum of Maxentius (died 312) outside Rome survive; in fact this was used for his son.[36]

The last of the series was the now vanished Mausoleum of Honorius (died 423), again containing the graves of many of his relatives. This was a circular brick building with a dome attached to Old St. Peter's Basilica, and demolished with it in 1519. It was typical of imperial mausolea after the empire converted to Christianity in being attached to a church or early Christian funerary hall (the origin of many of the largest basilica churches of Rome). Santa Costanza, for daughters of Constantine the Great is a surviving example, but unusual in still having much of its rich mosaic decoration.[37]

The mausoleum of Diocletian (died 312) was inside his massive Diocletian's Palace at Split, Croatia, and was later adapted to form the central section of Split Cathedral. This is octagonal on the exterior,[38] but circular inside; the elaborate carving of the columns has survived well, but is surrounded by lavish later church fittings.[39]

The church of Santo Stefano al Monte Celio or "Santo Stefano Rotundo" in Rome was, perhaps uniquely for its late 5th-century period, newly built as a circular church, apparently unconnected with any burial. It was long thought to have been built onto an earlier circular structure, but excavations have disproved this. The original construction, now much altered, had three concentric parts, all circular. Going from the centre outwards there was a 22-metre high central space, of the same diameter, surrounded by a much lower ambulatory, then an open-air space, except for four passageways, surrounded by another ambulatory.[40]

The Mausoleum of Theodoric in Ravenna, of 520, uses Roman construction techniques but is in an impressive but unclassical style, possibly borrowing from Syria; Theoderic the Great was an Ostrogoth "barbarian" ruler.[41]

Renaissance to modern

The tholos was revived in one of the most influential buildings in Renaissance architecture, the Tempietto in a courtyard of the church of San Pietro in Montorio in Rome. This was designed by Donato Bramante around 1502. It is a small building whose innovation, as far as Western Europe was concerned, was to use the tholos form as the base for a dome above; this may have reflected a Byzantine structure in Jerusalem over the tomb of Christ. The Roman Temple of Vesta (which has no dome) was probably also an influence. This pairing of tholos, now called a "drum" or "tholobate", and dome became extremely popular raised high above main structures which were often based on the Roman temple.[42]

Most of the proposals for rebuilding St. Peter's Basilica, the first by Bramante in 1506, included this combination of elements, at least on the exterior; as at St Peter's, false domes often gave a different interior view. The pairing of drum and dome was initially mostly used for churches, as at Les Invalides in Paris (1676) and St Paul's Cathedral in London (1697), but later other buildings, and continued until the 20th century at least.[43] The US Capitol is one of a number of buildings where a tholos is above the dome, serving as a base for the Statue of Freedom, as well as two much larger colonnaded ones below; versions of the formula have also been used in several (arguably most) American state capitols. The Panthéon in Paris is also topped by a tholos below a dome.[44]

_(37805843414).jpg.webp)

The Radcliffe Camera, built as a library for Oxford University in 1737, is one of relatively few large buildings after the Renaissance to use a purely circular plan, with little emphasis on the entrance, in a classical style that is full of complexities and looks back to Italian Mannerist architecture.[45] The Mausoleum in the park at Castle Howard in North Yorkshire, by Nicholas Hawksmoor (completed 1742), gives a "tragic" interpretation of the theme by making the columns large and close together and the dome low.[46]

Most preferred the Pantheon-style rotunda, with a pronounced temple front, or often several. The famous Villa La Rotonda (or "Villa Capra") by Andrea Palladio (begun 1567) took the Pantheon theme, but adding a columnaded temple front on four sides, to make a sort of Greek cross. There is a high and circular central hall with a large domed roof, but the building behind the porticos is actually square. This formula was often copied for country houses, as at Chiswick House (1725), designed by its owner Lord Burlington, and Mereworth Castle (1723) by Colen Campbell.[47]

The Rotunda at the University of Virginia, designed by Thomas Jefferson (1826) was much closer to the Pantheon, which was acknowledged as its model, and the tradition was still in use in the 1930s, when Manchester Central Library was designed and built by Vincent Harris, who often used an updated classical style. At its opening, one critic wrote, "This is the sort of thing which persuades one to believe in the perennial applicability of the Classical canon."[48]

St. Peter's Basilica, Rome

St. Peter's Basilica, Rome.jpg.webp) St Paul's Cathedral, London (1697)

St Paul's Cathedral, London (1697) Panthéon in Paris

Panthéon in Paris.jpg.webp) US Capitol tholos

US Capitol tholos Radcliffe Camera, begun 1737, James Gibbs

Radcliffe Camera, begun 1737, James Gibbs

Others

Notes

- ↑ Lawrence, 183

- ↑ Curl, James Stevens (2006). Oxford Dictionary of Architecture and Landscape Architecture, 2nd ed., OUP, Oxford and New York, p. 500. ISBN 978-0-19-860678-9.

- ↑ Yarwood, 5–6

- ↑ Lawrence, 187; Yarwood, 21

- ↑ See Thompson for a detailed excavation report.

- ↑ Thompson, 71

- ↑ Thompson, 147–151

- ↑ Lawrence, 185; Thompson, 128; Perseus database page

- ↑ Thompson, 129, 132

- ↑ Thompson, 69–71

- ↑ Lawrence, 183

- ↑ Thompson, 128

- ↑ Lawrence, 183–185 (185 quoted); Yarwood, 21

- ↑ Lawrence, 185

- ↑ Lawrence, 187

- ↑ Lawrence, 186–187

- ↑ Short video walk-through from Emory University

- ↑ "Rotunda of Arsinoe II", Emory University website; Lawrence, 187–188

- ↑ NRHP listing

- ↑ Lawrence, 186, posits a second conical roof over the flat roof shown.

- ↑ Yarwood, 47, 50, plan at 51

- ↑ Yarwood, 52

- ↑ Dyson, Stephen L. (1 August 2010). Rome: A Living Portrait of an Ancient City. JHU Press. p. 252. ISBN 9781421401010.

- ↑ Holleran, Claire (26 April 2012). Shopping in Ancient Rome: The Retail Trade in the Late Republic and the Principate. Oxford University Press. p. 161. ISBN 978-0199698219. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- ↑ Yarwood, 55–59

- ↑ Lawrence, 183; Yarwood, 34

- ↑ Lawrence, 183

- ↑ Perrot, Georges and Chipiez, Charles, History of Art in Phrygia, Lydia, Caria and Lycia, 45–49, 1892, Chapman and Hall (translation from the French); Lawrence, 183

- ↑ Lawrence, 189; "Algeria Mausoleum of Medracen in Danger" (PDF). ICOMOS. 2006–2007. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

- ↑ Lawrence, 189

- ↑ "Walk through the 2,000-year-old Mausoleum of Augustus, Rome's first emperor". The Art Newspaper – International art news and events. 2021-03-02. Retrieved 2021-12-15.

- ↑ Campbell, 31–32, 35–36, 41–42

- ↑ Campbell, 40–41; "Mausoleum Augusti", Gardens of the Roman Empire

- ↑ Quilici, L.; S. Quilici Gigli, DARMC; R. Talbert, S. Gillies; T. Elliott, J. Becker (2017-08-02). "Places: 422869 (Casal Rotondo)". Pleiades. Retrieved August 20, 2023.

- ↑ Yarwood, 109

- ↑ "Mausoleum of Romulus reopens after 20 years". The History Blog. 9 June 2014. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- ↑ Yarwood, 84

- ↑ As is the so-called Temple of Romulus in Rome, perhaps also an imperial mausoleum

- ↑ Yarwood, 60–62

- ↑ Claridge, Amanda. (1998). Cunliffe, Barry (ed.). Rome : an Oxford archaeological guide to Rome. Toms, Judith., Cubberley, Tony. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 308. ISBN 9780192880031. OCLC 37878669.

- ↑ UNESCO WORLD HERITAGE LIST Ravenna No 788, p. 60

- ↑ Freiburg, Jack, "Temple, Tabernacle, and Sepulchre: The Legacy of Bramante’s Tempietto", Sacred Architecture Journal, Vol 39, 2021; Summerson, 41–42; Loth

- ↑ Summerson, 41–42; Loth

- ↑ Loth

- ↑ Summerson, 42

- ↑ Summerson, 42

- ↑ Summerson, 55

- ↑ Holder, Julian (2007). "Emanuel Vincent Harris and the survival of classicism in inter-war Manchester". In Hartwell, Clare; Wyke, Terry (eds.). Making Manchester. Lancashire & Cheshire Antiquarian Society. ISBN 978-0-900942-01-3.

References

- Campbell, Virginia L., "Stopping to Smell the Roses: Garden Tombs in Roman Italy", 2008, Arctos, Vol. XLII, Academia.edu

- Lawrence, A. W., Greek Architecture, 1957, Penguin, Pelican history of art

- Loth, Calder, "The Tempietto, Grandfather of Domes", Institute of Classical Architecture & Art

- Onians, John, Art and Thought in the Hellenistic Age: Greek World View, 350–5 BC, 1979, Thames & Hudson, ISBN 0500272646

- Summerson, John, The Classical Language of Architecture, 1980 edition, Thames and Hudson World of Art series, ISBN 0500201773

- Thompson, Homer, The Tholos of Athens and its Predecessors (PDF), Hesperia, American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 1940

- Yarwood, Doreen, The Architecture of Europe, 1987 (first edn. 1974), Spring Books, ISBN 0600554309

_Petra_Jordan1461.jpg.webp)