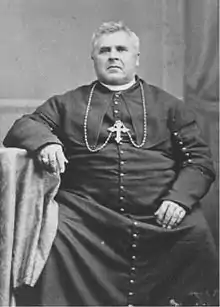

Thomas-Louis Connolly | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Archbishop of Halifax | |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Church | Catholic | ||||||||||||||||||

| Archdiocese | Halifax | ||||||||||||||||||

| In office | 1859 – 1876 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | William Walsh | ||||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Michael Hannan | ||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||

| Born | 1814 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 27 July 1876 (aged 62) Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada | ||||||||||||||||||

| Previous post(s) |

| ||||||||||||||||||

Ordination history | |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Source(s):[1] | |||||||||||||||||||

Thomas-Louis Connolly (1814 – 1876) was a Canadian prelate of the Catholic Church. Ordained a Capuchin priest, Connolly was, in turn, vicar general of the diocese of Halifax, Bishop of Saint John (1852–1859), and Archbishop of Halifax (1859–1876).

Life

Connolly was born in Cork, County Cork, Ireland. His father died when he was young, and he and his younger sister were raised by their mother. At school, he was a quick student and by age 16 had mastered Greek, Latin and French. He became a novice in the Order of Capuchins. At age 18 he went to Rome to complete his studies for the priesthood. He was ordained as a priest in 1838 in Lyons, France. He returned to Ireland, where he served as a prison chaplain in Dublin. When fellow Capuchin, Father William Walsh, was appointed bishop of Halifax in 1842, Father Connolly accompanied him to Nova Scotia as his secretary.[2] In 1845 he became Vicar-General and administrator of the diocese.[2]

Bishop of Saint John

Between 1845 and 1847, approximately 30,000 Irish arrived in Saint John, more than doubling the population of the city. During this period, Saint John was second only to Grosse Isle, Quebec as the busiest port of entry to Canada for Irish immigrants. The Roman Catholic population was largely impoverished and uneducated.

In 1852 Father Connolly was appointed bishop of Saint John, New Brunswick.[1]

In 1853, Bishop Connolly organized the construction of a cathedral for the city. Four hundred men gathered as volunteers in the work of digging the foundation at the site. Local quarries supplied the stone. The Gothic Revival cathedral and the stone, Gothic Revival/Italianate Bishop's Palace were recognized in January 2014 as The Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception Provincial Heritage Place.[3]

In April 1854 the ship Blanche arrived in Saint John, and brought cholera to the city. Of 5,000 people stricken, 1,500 died. The periodic outbreaks centered largely in the poorer Catholic district, where people were scarcely over the effects of ship fever (typhus). The care for orphaned children became a priority.[4] Bishop Connolly oversaw the opening of a Catholic orphanage run by the Sisters of the Sacred Heart.

Connolly also previously contacted the Sisters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul in New York to staff a planned orphanage. He was advised that while the community could not then send any sisters, they were willing to train any young women he might send to them. Honoria Conway entered the Sisters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul at Mount St. Vincent, New York. It is uncertain whether she entered with the intention of returning to Saint John to work with Bishop Thomas Louis Connolly, who had begun a number of initiatives on behalf of poor immigrants, or whether she intended to remain in New York. She and three companions returned from New York to New Brunswick and, on 21 October 1854, made their vows as Sisters of Charity of Saint John, a new diocesan religious congregation.[5] In Saint John, early sisters first lived in temporary housing provided by the bishop. He also encouraged the building of Catholic schools.[2]

Archbishop of Halifax

In 1859, Bishop Connolly was named as Archbishop Walsh's successor.[1] His nomination was strongly supported by both Archbishop Paul Cullen of Dublin and Archbishop John Hughes of New York. The four dioceses of Halifax, Arichat, Charlottetown, Saint John, and the newly created diocese of Chatham were under Archbishop Connolly’s jurisdiction.[2]

In the first he took an interest in the Canadian Confederation movement and actively supported it by writing pamphlets supporting the Union. After Confederation, he took no further interest in political affairs. He built numerous schools, churches, and a seminary. Archbishop Connolly attended the Vatican Council of 1869–70 and was among those opposed to the issuance of a Dogmatic Constitution regarding papal infallibility as he felt that the political climate was not right for the church to confirm the doctrine.

In May 1860, Archbishop Connolly, had his name inscribed on the roll of the Halifax Rifles Company, which was part of the Halifax Volunteer Battalion. There was concern at that time that the victorious northern armies of the United States would be directed against Canada. Archbishop Connolly in 1865 wrote:[6]

There is no sensible or unprejudiced man in the community who does not see that vigorous and timely preparation is the only possible means of saving us from the horrors of war ... To be fully prepared is the only practical argument that can have a weight with a powerful enemy, and make him pause beforehand and count the cost.

Connolly believed strongly that the Irish in Canada fared better than those in the United States.

He died in Halifax on 27 July 1876[1] at age 62. Nicholas Flood Davin wrote: "He belonged to the great class of prelates who have been not merely Churchmen, but also sagacious, far-seeing politicians and large-hearted men, with admiration for all that is good, and a divine superiority to the littleness which thinks everybody else wrong."[7]

See also

- Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception (Saint John, New Brunswick) – cathedral in Saint John, New Brunswick, Canada

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 Cheney, David M., "Archbishop Thomas Louis Connolly, O.F.M. Cap.", Catholic Hierarchy

- 1 2 3 4 Flemming, David B., "Connolly, Thomas Louis", Dictionary of Canadian Biography, Vol. 10, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 1972

- ↑ New Brunswick Department of Tourism Heritage and Culture, Heritage Branch

- ↑ Kennedy SCIC, Estella. "Immigrants, Cholera and the Saint John Sisters of Charity", CCHA, Study Sessions, 44(1977), 25-44

- ↑ "Sisters of Charity (Saint John, New Brunswick)." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 3. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1908. 9 Jan. 2015

- ↑ Quigley, J.G., "A Century of Rifles", The Atlantic Advocate, May 1960

- ↑ Chisholm, Joseph. "Archdiocese of Halifax." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 7. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1910. 9 Jan. 2015

References

- The Canadian Portrait Gallery, Volume 2. John Charles Dent. 1880.

- "Thomas-Louis Connolly". Dictionary of Canadian Biography (online ed.). University of Toronto Press. 1979–2016.

Further reading

- Farrell, John K. A., "Roman Catholic Influences Supporting Canadian Confederation", The Catholic Historical Review, Vol. 55, No. 1 (Apr. 1969), pp. 7-25, Catholic University of America Press